Some time towards the end of last year, my niece Roz emailed me to the effect that she was in London, and would I care to meet up with her for some coffee? I was intrigued. Because of our differing political views, Roz and I have had a polite but somewhat distant relationship. She is into feminism and environmentalism. I am into, well …: see all my other postings here. What was going on? Why this meet-up? I knew some unusual game was afoot. But what?

We duly met up, and after some further polite chit-chat, what was afoot was revealed. Roz had written a crime novel, called The Devil’s Dice. This book, she said, was in the process of being published, by a real publisher of the sort that you have heard of. I like crime novels, and I like detective dramas on television. And I know how hard it can be to write anything even as long as a longish blog posting (such as this one is (you have been warned)), let alone a book. So, I was impressed.

Although she didn’t spell this out, it was clear that Roz was then at the stage of communicating with everyone she could think of who might be able to help her sell this book. Which also impressed me. Good for her. And good for her also, and good for me, that she was content to include me in this process. Later, an advance copy of the book arrived at my home, in a bright gold bubble-wrapped package, together with some chocolate dice, in a little bag made of bright red netting.

I read the book, and found it thoroughly absorbing and entertaining. She writes really well.

A quote from the book? Try the dedication:

To my parents.

Thank you for your support and encouragement, and advice on how to kill people.

Roz’s mum, my older sister, was a National Health Service doctor, and her husband was a psychiatric social worker. Short of having parents who were directly involved in the criminal justice machine, like detectives or coroners or forensic pathologists or suchlike, a crime writer couldn’t ask for a better start.

Why is crime fiction, especially crime fiction where the crime in question is murder, in books and in movies and on the television, so very popular, at a time when the actual murder rate seems, touch wood, to be in decline? I sometimes wonder at what point the number of actual murders in my country was overtaken by the number of fictional murders. It must have been quite a while ago. In just one typical night of British television, the body count often comes to more than a dozen. Why this fascination, concerning something that, for real, is so compartively rare?

Part of the appeal of crime fiction is that it handles the dark and disappointing side of life, the failure and frustration, and the consequent downright evil that potentially resides in all of us, yet does this in a way that makes the contemplation of such personal tragedies and moral disasters palatable and entertaining. In the end, in crime fiction, everything gets sorted out, at least in the sense that you find out what really happened and who did it. Evil is confronted, even wallowed in, but is eventually explained and punished, and thereby kept at bay.

But although a hero, the detective protagonist who is at the centre of most crime fiction is not always a hero of the usual sort, the sort familiar from other sorts of dramatic and fictional entertainment, such as romantic comedy or dramas based more on action and daring-do. In most popular dramas, especially in the movies, the leading characters are typically quite young and lacking in any serious blemishes, either moral or physical. Oh, there are lots of “characters” of various sorts involved, of varying degrees of imperfection, including, as often as not, a seriously wicked senior villain. But these characters are strictly secondary, and they cause the leading characters to shine all the more brightly by way of contrast.

Crime fiction is often like this also, especially on television, and especially when the television show was made in America. In many American police shows, implausibly “diverse” assemblages of implausibly good looking people are to be seen solving crimes and triumphing over criminals, night after night. The lady detectives in particular, in American police shows, are often spectacularly good-looking, being portrayed by actresses who have either just had careers playing romantic leads in the movies, or who can still realistically hope to have such careers in the near future.

But as often as not, in crime fiction, the central puzzle-solving protagonist who cracks the case is at best decidedly eccentric and in general no sort of conventional romantic lead at all. Often quite old, often rather ugly, perhaps absurdly vain or, more often these days, just rather grumpy and depressed. And yet, this flawed and peculiar individual is all the more appealing – all the more heroic – as a literary companion, because so flawed and peculiar. Insofar as physically terrifying stuff still needs to be done by our hero or heroine, then his or her imperfect physique makes that also all the more heroic and impressive.

After all, what happens to the public when it gets to a certain age? Contemplating heroic and impossibly attractive young protagonists loses some of its appeal, when you are busy declining into being a rather secondary sort of character yourself. You can still admire young and glamorous detectives, but you can no longer plausibly identify with them. So, you are liable to want at least some of the people solving your fictional crimes to be less like romantic leads and more like you. An inquisitive old spinster, perhaps. Or a bloke with a bit of a paunch or a bit of a temper or a bit of a drug habit of some sort, and a bit lonely, maybe divorced. Ian Rankin’s hugely popular Inspector Rebus books are particular favourites of mine, and John Rebus suffers from all of those afflictions. The detective stories now being written by JK Rowling – aka (for these purposes) Robert Galbraith – feature a detective who is still quite young and good looking, but who has had one of his legs blown off when he was in the army.

If there is a conventionally perfect star, in crime fiction, that star is typically the puzzle of the crime itself and the manner it which it is solved. All this, unlike the detective who cracks it, has to be pretty much perfect. If not, there will be complaints.

And here we come to another of the attractions of crime fiction. Most crime fiction, more or less, embodies the idea that life can be made sense of. Apparently mysterious things and seemingly baffling events can, in the end, be understood and logically explained, sometimes even in a big set-piece speech delivered to a big audience consisting of all the suspects, with the actual miscreant or miscreants being triumphantly named, shamed and led away to their punishment.

This idea that things make sense, even and especially if at first they do not, is no small matter. Beginning with the pictorial arts, circa 1900, and more recently taking root in the humanities departments of the Western world’s universities, the opposite idea has been spreading, to the effect that no truths can be logically deduced about the world that are worth learning. Worse, it has been claimed that truth and logic themselves are merely bourgeois – more recently, merely white – delusions.

Crime fiction, most of it, still sides with those who believe that the truth of things is there to be sought out and identified. If the world itself has become a place that doesn’t make as much sense as it should, because a lot of the people who ought to be making the most sense of it have given up, well, those of us who still try to live sensible and decent and truthful lives can at least escape for a few hours into an alternative universe where the world definitely does still make sense, both logically and morally, and despite all early appearances to the contrary. We can pick up a detective novel, and inhabit, at least for a few hours, a world in which good people can at least try to win and in which people who have given up even trying to be good mostly lose.

The Devil’s Dice by Roz Watkins embodies most of the virtues alluded to above. It is, in most ways, and so far as I can judge from my somewhat limited reading of this genre, a fairly conventional crime thriller. Her lead detective is a satisfyingly imperfect and individual creation, somewhat tubby, with a limp and a past full of issues, and a mother and a grandmother demanding more attention from her than she can easily spare. Insofar as there are unconventionalities, for instance in the motivations of the murderer, these are features rather than bugs.

If I now refrain from offering a conventional review of this book, this is because the conventions of writing such reviews take a bit of getting used to. When one of us here at Samizdata reviews the sort of book we usually review here, we summarise what it says and what it concludes, and we say whether and how much we think the sense that the author thinks he or she has made of things makes sense to us. But if you are reviewing a crime thriller, the absolute last thing you must do is tell everyone what happened. So, no spoiler alerts here, because no spoiling. Instead, I refer readers to appropriately vague and adjectival reviews of this book done by regular writers of such reviews, which I got to by following Roz on Twitter.

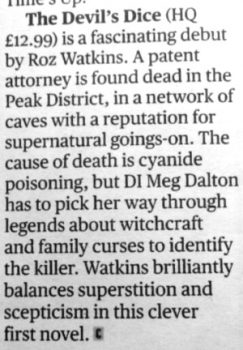

There is this review, and this review, and this review, and this review, and this review, and this review. Roz has also retweeted various tweets about more reviews which are now piling up at Amazon, almost all of them five-star. Perhaps best of all, in the latest Sunday Times, photoed by Roz’s brother down on the South Coast and then gleefully tweeted to all her followers by a snowbound Roz up in Derbyshire, this:

The feature of The Devil’s Dice that reviewer after reviewer has kept on noticing is the somewhat unusual setting in the Derbyshire Peak District, which is near to where Roz lives. In most crime thrillers that I know of, the setting is either an urban dystopia, as in the Rebus books, or some sort of suburban or rural or provincial idyll of seeming perfection, beneath which lurks … blah blah, in the manner of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple stories, or of the Inspector Morse books and television shows, and now of the Morse spin-off detective, Lewis. Actually, people who live in nice places like the more affluent and learned bits of Oxford, or in cute villages in the Cotswolds, very rarely murder each other, but you wouldn’t know this from crime fiction.

The setting for The Devil’s Dice is different from either of the above conventionalities. It is rural but creepy, with lots of emphasis on scary folk tales and curses and whatnot. For a townie like me, the countryside of England looks, from afar, like a giant theme park, where all the monsters and witches and goblins of the past have all been thoroughly tamed. Through these perfectly preserved and impossibly picturesque parts of England, television travel presenters now roam, meeting nice but entirely friendly and unthreatening local historians and they have nice little chats with them. The English countryside is, for me, the landscape equivalent of those impossibly attractive young American lady detectives.

It would seem that the explanation for this deviation from crime fictional routine is that Roz’s story began, for her, not as a crime thriller, but more as a horror story, more of a psychological thriller. In those sorts of books, I’m guessing that the countryside often features as a scarier sort of place than it mostly looks to the likes of me or Agatha Christie when we gaze out upon it, through a car or train window.

But then what happened was that Roz allowed a detective to insert herself into her story and to make sense of everything, and that character just grew and grew. You can read about that in this blog posting, which includes a bit of very informative Q&A with Roz. (The reviews, tweeted and short, or blogged or Amazonian and longer, just keep on coming.)

Besides all that sense-making, other aspects of crime fiction are perhaps a bit less admirable. Getting back to the grimness thing, and how crime fiction enables people to confront the ghastlinesses of human existence, it only requires a slight tilting of the balance in favour of the bad guys and the bad places, and crime fiction can become the vehicle for a relentless and excessive pessimism about humanity and its possibilities and possible futures.

I recall reading once how, just after World War 2, American Communists piled into crime fiction, both with books and with black-and-white movies, to try to persuade America that it was on the road to hell, rather than headed towards the much happier and more abundant consumer society of the fifties and onwards that actually transpired. Said these politically radical pessimists, to late 1940s America: these mean and monochrome streets along which Bogartian detectives now walk are just going to get meaner and meaner. As for the nicer bits of the world, with their nice houses, nice furniture and affluent surroundings, well, the meanness there is even meaner. A constant theme of crime fiction is how the nastiest things get done in the nicest places, that the skulduggery perpetrated at the wrong end of town is often traceable to affluent villains hidden away in the nice end, in a way that thereby links the urban hell aspects of life to the seemingly perfect bits. Those American Communists did all they could to spread the message that all of this was just going to get worse and worse, unless politics was turned upside down in a way that actually would make everything very mean for real.

I’m guessing that maybe a few of the favourable reviews for The Devil’s Dice were written by people for whom Roz Watkins’s and crime fiction in general’s stress on the dark side of life, on the “Noir” aspect of things, is a feature of just the kind that those American Communists were also keen to stress, and for similar reasons. Even in the prettiest places, places like the Peak District, life is nastier than you could ever imagine! Them talking up books like The Devil’s Dice means that optimists about mankind’s future like me are overwhelmed by a tide of pop culture pessimism. In general, we seem now to live in pessimistic times.

One of the more “political” moments in The Devil’s Dice occurs near the beginning, which means that I won’t get into any spoiler trouble if I now review it, somewhat unfavourably.

We followed her into a vast kitchen complete with granite worktops, slate floor and the aroma of fresh bread. It was the kind of kitchen you see in those awful, aspirational homes magazines at the dentist; the ones designed to make you dissatisfied with your perfectly adequate house – if indeed you have an adequate house, which I didn’t.

Grace installed us at the table and asked if we wanted coffee. I nodded and she popped a sparkling burgundy capsule into a sleek, black machine.

‘I know they’re an ecological disaster, but …’ She looked round and shrugged. I shrugged back – the shrug that defined the whole of Western civilisation.

Come again. A couple of women in a posh kitchen shrug about the amount of plastic waste that Western civilisation spits out? And that’s Western civilisation? How about a billion or more desperate souls in desperate places being lifted, during only the last handful of decades, out of abject poverty into mere poverty, from a rural hell to a more urban not-such-hell? Does that not count for anything? Does that not get included in the definition of Western civilisation? And how about all the other multiplying pleasures that we in the luckier and richer parts of the world can all now enjoy in ever greater abundance, like crime fiction and complicated chocolate?

I know, I know, it’s only a story. And writers don’t necessarily agree with what their leading characters are thinking, and yes, the idea is to create an atmosphere of general policewoman’s-lot-is-not-a-happy-one grumpiness, and maybe I’m making far too much of a fuss about one throwaway thought. Above all, one can greatly enjoy a book about the exploits of a detective with whom one does not agree about, you know, the bigger issues. It is enough that the detective chases after people who do bad things. I don’t share all of Rebus’s views about politics or religion either, and in general some of my closest friends are people I often strongly disagree with. But I think I hear Roz in the bit I just quoted above, and if that’s right, then I do not agree with her.

Much joy has been expressed on the social media about that golden bubble-wrap packaging of the advance copies that we early readers got through the post, and those chocolate dice in their little red bag. But, was that not also something of an “econological disaster”, suggestive more of chick lit to be read on an expensive foreign beach than of a gloom-ridden crime story? Would DI Dalton have been impressed by such plasticated commercialism? I reckon there’d have been another shrug about that.

But, what the hell. Those American Communists didn’t prevent the Affluent Society that actually happened after they’d done their worst, the very same Affluent Society that DI Dalton now shrugs at. Fiction reflects the perceived and feared future at least as much as it shapes the actual future, arguably far more so. The world is not about to be smothered in plastic waste, but people can be forgiven for fearing this, given what the ideological descendants of those American Communists have been saying more recently.

And life can indeed be very grim in lots of other ways, for lots of people, now, after which we will all die, often very painfully. Reading books like Steven Pinker’s hugely optimistic The Better Angels of Our Nature, which is all about how everything in the world has actually, on the whole, been getting nicer, despite what you read everywhere else, won’t get you onto the housing ladder if you aren’t on it already. And if you are, you may then face a lifetime of stressful clambering and clinging on rather than the steady and confident climb that you had been hoping for. Crime fiction at least consoles such strugglers by showing them a world populated by people, especially the murder victims and their murderers, who are doing a lot worse even than they are.

Speaking of not having an adequate house, as I just quoted Roz’s DI Dalton saying, one of the recurring themes of the Rankin’s Rebus books, in among all the heroin addiction and murder and mayhem, is the relentless rise in the cost of housing in Edinburgh and its surroundings. Rebus has a flat in the centre of town, which he bought way back before the first book in the series. For Rebus’s younger colleagues and underlings, especially in the later books, nice places to live keep on getting harder to find, and the commute gets worse and worse.

All of which goes to show that crime thrillers are an excellent way for regular people to ruminate upon the state of the world and its various woes, but again, in a way that keeps such arguments at arm’s length. Yes, think about these things, in the way we do here at Samizdata, and as I have just been doing, but then, get back to the story. That’s what really matters. If that grabs you, then all else is secondary.

And as I say, The Devil’s Dice did grab me, despite any incidental grumbles I may have had about how its leading character merely thinks. And if you think that I am hopelessly biased in Roz’s favour, which I am, then let me also tell you that soon after I had finished reading The Devil’s Dice, a friend came to stay with me and he read it too, and he was grabbed. In fact, by the end, he found himself being downright moved, by some of the, er, issues that the book deals with. (To say any more about those issues than that would be to enter spoiler territory. Sorry.) I also lent him one of the Robert Galbraith books, but that did not appeal.

Aside from the story told in The Devil’s Dice, the other story that interests me here concerns how well The Devil’s Dice is now doing and will do. ITV have bought the television rights to it, but I don’t know if that reveals serious televisual intent or is a mere precaution. Maybe the television people do that to all the half-decent crime fiction books, but only make real shows out of a tiny fraction of the stories they have bought. Don’t know.

Maybe I’ll get to ask Roz about that, because I hope, the weather between here and Derbyshire permitting, to be seeing her again this evening. A few days ago, she did the official launch for The Devil’s Dice at Waterstones, in Derby. Tonight Roz and another lady crime writer will be speaking at a shared book event in Waterstones, Piccadilly, London W1. I will definitely be at that.

For me, one of the more interesting aspects of the story of this book, as opposed to the story in it, is that there will soon be another such book.

When Roz first told me about The Devil’s Dice, at that meet-up last year, she further told me that her publishers had said that they were only willing to publish The Devil’s Dice if Roz also produced acceptable first drafts or outlines or whatever of two more such books, featuring the same lead detective, and promised then to finish them. This, if you think about it, makes perfect commercial sense. A publisher cannot be sure that any particular book they publish will be a hit. Many books are published, but only a few do really well and there’s no accounting for taste. But, if the author has at least promised to write (and preferably has already written) several books featuring the same leading character, then that means that if the first book does do well, the rewards to the publisher will be far greater than they would be from just the one book, no matter how successful and admired it might prove to be. Contrariwise, if the first book doesn’t do that well, later books might do better, and retrospectively rescue the first one, so to speak. (I recall Ian Rankin writing to the effect that this happened with his first Rebus book, which caused no very great stir, at first.)

Something very similar applies to the experience of reading crime fiction books. If you are wondering whether to give DI Dalton and her adventures a go, it is good for you to know that if you do take a liking to her, you’ll have further chances to get to know her better in the future. Just like publishers, readers “invest” in characters, and appreciate knowing that if their early investment pays off, there’ll be further pay-offs of pleasure, in the form of all the later books in the same series. I only started reading the Rebus books quite late on, when there were already a dozen or more of them out there. And a big part of what encouraged me to get started on them was that I knew that if I liked the first one I read, there would then be plenty more to get stuck into.

Presumably the television people will be similarly influenced by the fact that there will be more DI Dalton books in the Roz Watkins pipeline, for them to cash in on if they decide to give the first book a go and it’s a hit.

In general, if you have written a book, and you are fretting about how to publicise that book, the best answer of all is: write another book, and then another, and then another …

So, the fact that there will soon be another book in the DI Dalton series, Dead Man’s Daughter, which is now nearing completion, is significant. Read a little about that book at the Roz Watkins website, under the heading of “books” with an s, under a similar bit about The Devil’s Dice. As all those reviewers are saying, concerning whatever further DI Dalton stories emerge: “I can’t wait!” Me, I can wait, if only because like everyone else, I will have to. But I am greatly looking forward to seeing how all this turns out, both for DI Dalton and for her creator.

In the great anthem by that great late Englishman the punk rocker Ian Dury:

There are jewels in the crown of England’s glory

And every jewel shines a thousand ways

Frankie Howerd, Noël Coward and garden gnomes

Frankie Vaughan, Kenneth Horne, Sherlock Holmes

Monty, Biggles and Old King Cole

In the pink or on the dole

Oliver Twist and Long John Silver

Captain Cook and Nelly Dean

Enid Blyton, Gilbert Harding

Malcolm Sargeant, Graham Greene (Graham Greene)

All the jewels in the crown of England’s glory

Too numerous to mention, but a few

And every one could tell a different story

And show old England’s glory something new

Nice bit of kipper and Jack the Ripper and Upton Park

Gracie, Cilla, Maxy Miller, Petula Clark

Winkles, Woodbines, Walnut Whips

Vera Lynn and Stafford Cripps

Lady Chatterley, Muffin the Mule

Winston Churchill, Robin Hood

Beatrix Potter, Baden-Powell

Beecham’s powders, Yorkshire pud (Yorkshire pud)

With Billy Bunter, Jane Austen

Reg Hampton, George Formby

Billy Fury, Little Titch

Uncle Mac, Mr. Pastry and all

Uncle mac, Mr. Pastry and all

allright england?

g’wan england

oh england

All the jewels in the crown of England’s glory

Too numerous to mention, but a few

And every one could tell a different story

And show old England’s glory something new

Somerset Maugham, Top Of The Form with the Boys’ Brigade

Mortimer Wheeler, Christine Keeler and the Board of Trade

Henry Cooper, wakey wakey, England’s labour

Standard Vanguard, spotted dick, England’s workers

England’s glory.

Very interesting. I am a great reader of crime fiction, and this sounds reminiscent of Stephen Booth whose stories are set in the Peak District. For many stories in this genre the crime and solution merely provides the framework for a host of interesting characters, for instance Hazel Holt’s novels or for a more exotic setting, Donna Leon in Venice.

I am repulsed by crime fiction, I think because I may regard it as gawping at murder and, I fear, cheapening human life, as if fascination with murder in a way gives it a glamour and an appreciation when it should be condemned, and wonder if it cheapens respect for human life. I am probably out on a limb there, and not suppressing my inner Puritan. I also know many who adore crime fiction and may well get a copy as a present.

Having worked briefly on both sides of the criminal justice system, I find the criminal element so repulsive and unsympathetic that I can have no sympathy for them at all. I also tend to regard matters in what I have seen of crime drama as perhaps not being sufficiently driven by the demands of the law and the quality and admissibility of evidence, and the prosecutor might be a better focus than the detective as the one who would carry the agonising burden of formulating a case.

Explore Suffolk.

Short of having parents who were directly involved in the criminal justice machine, like detectives or coroners or forensic pathologists or suchlike, a crime writer couldn’t ask for a better start.

The crime writer Anne Perry does win (in a morbid sense) on this score, given that at age 15 (as Juliet Hulme) she committed one of the most notorious murders in the history of New Zealand – later dramatised in Peter Jackson’s film “Heavenly Creatures”.

1. Doctors are the man-killing professional champions by a long way.

2.Fictional murders are NOTHING like real murders, in any way except someone dies. In thirty years of 20-50 a year,I can think of maybe a half dozen that might make a mystery story.

3. You’re wrong about the Keurig comment, I thought it was a lovely sneer at the bogus “environmentalist” and parlour pink/limousine lefty.

An entertaining article. I may even read the book, though it is not the sort of thing I usually like.

“A couple of women in a posh kitchen shrug about the amount of plastic waste that Western civilisation spits out?”

In isolation, encountering that in any novel is no problem. People do shrug about plastic waste and they do have throw-away thoughts that it is some sort of metaphor for western civilisation. No reason at all not to see it happen in a novel. But Brian told us that the author is “into feminism and environmentalism”, which might hint at more of a problem. Except that in a crime novel it is unlikely to surface as a problem. The logic of a murder mystery is unlikely to be affected by such ideas.

I often struggle with this sort of thing in science fiction novels. Because part of the purpose of science fiction is to build a world, the author having certain kinds of ideas will affect the logic of that world. The worst part is that it could take a long time to figure it out, and it could break things retrospectively (for example the end of an epic saga revealing that the main mystery hinged on some nonsensical economic idea).

I suppose it is possible that a crime novel could have a tiresome theme, such as the villain turning out to be an evil capitalist deliberately polluting the river to make money, but such a character might exist in the real world without the logic of the real world being broken.

Anyway, I am not put off, and if the novel “grabs” people, it is likely well paced and plotted and I may well enjoy it a lot.

I know what you mean. Yet funnily, I enjoy Warhammer 40k fiction, set in an utterly dystopian retro-techno-dark ages that revolves around a ghastly totalitarian interstellar state with all the most charming features of Nazi German and the Soviet Union but with Nigerian levels of efficiency & bureaucratic probity, all set to a droning soundtrack like Medieval Catholicism-at-its-most-lunatic vibe, where disagreement is not just frowned upon, it is heresy against the undead God-Emperor. Crazy fun 😈

Likewise, some crime fiction can be interesting even if the people involved are (by our standards) politically ‘incorrect’ 😛

TPH – thank you for the Ian Dury reminder. The man could turn a phrase and play with words like few others.

Regarding the story described, am I the only one who sense a touch of the venal about this? I think Uncle Brian’s politics are icky, but I’ll still try and tap his network to sell my book? Maybe I’m just too touchy.

llater,

llamas

who could be the ticket man at Fulham Broadway station.

llamas

You are too touchy, way too touchy. Family trumps mere political opinions, every time. Nothing about Roz’s recent contacts with me has struck me as “venal”, and I very much hope you ARE the only one who sees it this way. Besides which, why the hell shouldn’t she use me and my “network” to help her sell her book, if I am willing to go along with this, and I am, very. I am thoroughly enjoying everything about this whole episode. I love being quite closely related to someone who just might turn into a seriously successful and seriously popular author, as I think I made very clear. If I didn’t, I make it clear now. Watching Roz find something to make a living at that she really enjoys, and is really good at, and which people generally are inclined to notice, has been an unalloyed pleasure.

I’ll tell you what would have upset me, even if you might have thought it less venal and undignified. If Roz had NOT told me about this book she’d written and was getting published, and if she had not even told me that there was an event in its honour in a big London bookshop literally a walk away from my home (this was last night, as mentioned at the end of the posting), now THAT would have really hurt. As it was, I invited friends along too, and we all had a great time, as did everyone present. Not the least of the evening’s pleasures for me was that I also met up again with Roz’s brother, who is a great guy. Used to be a British Airways pilot, although he has just stopped doing that. It will also be fun seeing what he gets up to next.

Roz is not just a very good writer, she is also an excellent and highly effective speaker, both in interview (she did an interview on the internet yesterday afternoon which I watched live) and when speaking on her feet, as she did last night. No histrionics, just lots of quiet sincerity and a pleasingly downbeat sense of humour.

On the TV front, it seems that there is a real possibility that this might happen. A scriptwriter was appointed some while ago and is apparently hard at work. Again, what exactly that might mean is hard for an outsider to that world to know, but someone is at least serious about trying to get The Devil’s Dice onto TV, and if that happens, watch the books sales take off. And watch me swank about how she’s my niece, just like I am now.

Venal? This is the kind of thing that makes life worth living.

Agreed about that Ian Dury lyric. I’d forgotten it. Lovely to see all the words laid out like that. And there’s a lovely “it takes all sorts to make a country” feel to it, just as it takes all sorts to make an extended family.

Now, about that rather distant cousin of mine from way back, who invented the Googly …

Brian Micklethwait – Fair enough, I stand corrected. Only goes to show how easily the nuance can be lost when the description is written down.

However, it’s been my observation that family quite-often does not trump political opinions. I’m glad that is not the case in your family. I hope she is successful.

llater,

llamas

llamas

Thanks for that response, to my rather over-the-top response to your first response.

Yes, I’m sure you’re right that politics does often spoil families.

New development: The book just got a very favourable write-up in … The Daily Mail:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/books/article-5533559/CRIME.html

Not, until today, Roz’s favourite newspaper, and still not. But from her tweet on the subject, which was how I heard about this, it is clear that she is well aware of the humour of the situation.

Rob Fisher, turn on the Saturday morning cartoons. EVERY villain is an evil capitalist deliberately polluting the river (or something else) to make money.

As usual, i am late to the party. In this specific instance, it is partly because i have been busy reading a gripping detective story (Sidetracked, by Henning Mankell) and an even more gripping spy novel (Red Sparrow).

My first comment is about why detective fiction is popular, and i apologize for writing this w/o cross-referencing Brian’s OP, for brevity.

As it happens, i recently re-read a micro-essay by Andrew Greeley who submitted that there are 3 reasons why people read mysteries: the puzzle, the story, and the characters.

To which i would add, the setting.

For me, the appeal of Sherlock Holmes is about equally distributed between the puzzle, the central character, and the setting in Victorian London.

The appeal of my favorite mystery canon, Nero Wolfe, is mainly due to the central character (who has an ego even bigger than mine), but also the other characters, the story (not the puzzle), and the setting in a New York in which bourgeois values were still prevalent. (The author died in 1975.)

The appeal of Agatha Christie mysteries is mostly about the puzzle, but occasionally also the setting in the English countryside.

What about the Mankell/Wallander novel i just finished reading? right now, i am not sure why it was gripping, but it was probably the story and the puzzle: the Wallander character is interesting, but basically i don’t much like him.

The setting does not make for gripping reading, but it is worth thinking about: Mankell describes some serious Swedish social ills (possibly magnifying them out of proportion, for all what i know), but most people on this site would probably disagree with what Mankell seems to suggest: that the solution to those problems is more state welfare, not less.