Trevor Dupuy was a US soldier and a military historian who took a statistical approach to evaluating combat performance. He paid particular attention to casualty statistics. Casualties – in case you did not know – include deaths but also include wounded, missing and captured. They answer the general’s question: how many men do I have who are able to fight?

Of course, statistics aren’t everything. For instance, the North Vietnamese took vastly more casualties in the Vietnam War than the Americans but they still won. But all things being equal, being able to kill more of your enemy than he can kill of you is a good thing to be able to do.

In A Genius for War Dupuy enquired into the nature of the German army. He found that the statistics told a remarkable story: the German army was very good and had been for a long time. From the Franco-Prussian War to the Second World War the Germans were consistently better at killing the enemy than the enemy were at killing them.

Now you may be thinking that such comparisons might be skewed due to the Russians and Dupuy found that that the Russians were indeed every bit as bad as you might think. But even when he removed the Russian numbers Dupuy found that the Germans still held a clear and consistent superiority over the French, British and Americans. This superiority existed regardless of whether the engagement was offensive or defensive.

Chauvinists might be surprised to learn that there seems to have been no great difference between the western allies. French and British performance was more or less equal in the First World War. British and American performance was more or less equal in the second. The Americans in the First World War and the French in the Second are special cases.

Having satisfied himself that the German army was indeed superior, Dupuy asked why this was. His key finding was that there seemed to be nothing inherent in being German. Dupuy found a number of historical examples where the Germans proved to be anything but good fighters. These included largely-German units in the American War of Independence and various battles between German mercenaries and the Swiss.

So, if being German didn’t make you a good soldier what did? Dupuy’s theory was that it was all due to the German General staff. So what was so good about the General Staff? Dupuy listed several criteria. These included selection by examination, historical study and objective analysis. In other words it was an institution that thought seriously about war.

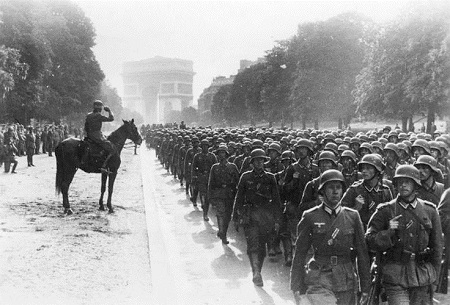

The doctrine that all this thinking led to might be summed up as bold plans tempered with flexibility. Perhaps the best-known example of bold planning was the invasion of France in 1940. No one on the allied side thought a tank-led thrust through the Ardennes was possible. But it was and France collapsed soon afterwards.

As many of you will know far from being an official General Staff masterplan the invasion of France was in fact dreamt up by Erich von Manstein in opposition to his superiors. But Manstein was still every inch the General Staffer.

Flexibility was also important. Contrary to the stereotype the German army did not want blind obedience. Not only did it allow subordinate commanders to figure out how to achieve their objectives but if opportunities arose which were unforeseen they were not only allowed to take advantage of them but expected to do so. “His majesty made you a major because he believed that you would know when not to obey his orders.” as Prince Frederick Charles put it.

I would like to thank Perry de Havilland for pointing me in the direction of Dupuy and his works.

Well, both my grandfathers and my father survived their respective wars. I don’t know how much they achieved as far as the killing the enemy goes, but they certainly contributed to the not killed column.

My Dad told me of his experience in the infantry (before he transferred to the paratroops) and some commanders were clearly not very flexible.

Also, Patrick, any links to Dupuy’s sources?

The dismissal of the quality of the individual german soldier should not be so quickly done. It may be so, but the evidence presented (American independence, mercenary units) does not suffice. It precedes a huge part of that military skill, the unification of Germany in the mid-19th century and implementation of Prussian military training to the whole male population. Now, here the two factors interact, as it is the general staff who creates the training, I suppose. But by the Franco-Prussian war, the german military could count on more better trained soldiers than any power on the continent. In addition, Prussian culture exalted military values, and so drew the best and brightest to the military field. Even that consummate politician, Otto Von Bismark felt it necessary to secure himself an officer’s commission in the reserves, so great was the social benefit. Prussia’s domination of the rest of Germany spread these values via the germanization and kulturkampf movements to the larger population. Yes, the general staff was of high quality, and they allowed flexibility, which is good. But other factors produced this and other advantages as well.

I’d say the view the British & American armys’ performance were roughly equal in WW2 is a pretty profound statement.

At the outbreak of war, in ’39, didn’t have an army capable of engaging in a war against a major power. Why would it? The major powers were the other side of great oceans. Apart from a brief essay in the latter part of WW1, it had no experience of doing so. In contrast, the British Army’s job was supposed to be doing exactly that. A couple of decades before it had just finished four years of fighting such a war & much of its higher ranking officer corps had served in it.

So, in equating the performance of the two armies, one’s including in the learning process the Yanks went through in turning military planning theory into practical experience. And didn’t they learn fast? It’s a short interval between the drubbing at Kasserine to the lightning thrust took Messina.

I’d say, if you took the period Overlord on, the US Army wiped the floor with the Brits. Could any British general have managed Patton’s turning the axis of advance of four divisions 90 degrees to counter the Ardennes offensive in 48 hours? Had the tactical foresight to have the battle plans to do so draughted, so it only took a two word order to set them in motion when requested? And worth mentioning the tenacity of the ordinary GI, when the attack unexpectedly hit a weak & unprepared flank, in blunting & holding the German advance long enough for the counter. Troops with a few months experience against formations with nearly five years of battle hardening behind them.

How’d I manage to leave “American” out of the second sentence after ’39? The mysteries of the interweb. Sure you got the drift, though.

That’s history and may not reflect the modern German army. My son in law served in it 20 years ago and thought it was a joke even then. Since, the German army, like all European armies, has gotten much worse.

The Euros were incapable of transporting troops to Yugoslavia when that crisis broke out, and they ran out of smart bombs during the Libyan adventure. The UK, France and Germany together field only 400 to 500 main battle tanks.

The UK has only 56, a single regiment. With numbers that low, you cannot train formations larger than platoon and company.

Even the US has converted most of its armored formations to infantry. NATO is in big trouble if Russia ever gets around to serious mischief.

@bob sykes,

What you say is true, but partly irrelevant. Yes there are fewer main battle tanks, but there is less need for them. We also have a lot fewer fighter planes. Who are they going to fight? The ISIS armor and fighter columns? You’ve got to train and gear for the battle you have on hand, and right now that’s drones and a lot of mechanized infantry. It’s not like we can’t build tanks faster than the Russians.

You are correct about the state of european militaries, though. Politics is downstream from culture, and the military is downstream from politics. Without a nation that can produce the sort of young men who excel at military matters, and induce them to serve, and reward them commensurately for it, military skill and effectiveness will suffer. Technology can paper over the gaps for a while, but eventually, the cultural failure will be laid bare.

“The UK, France and Germany together field only 400 to 500 main battle tanks.

The UK has only 56, a single regiment.”

To what purpose? Iraq, both episodes, definitively proved main battle tanks cannot survive on a modern battle field if your opponent has air superiority. If you have air superiority, you don’t need tanks.

And logistics. To get tanks to a battlefield requires an enormous logistics train. Basically, access to a major port & the ship assets to transport them. The British Army doesn’t have access to any ship assets to ship its tanks. It’d have to rent them. So the lead time to putting tanks on the battlefield, in anything but your backyard, is in several months.

Two thoughts spring to mind

a) any assessment of the relative quality of the NCOs’ and their training?, and

b) did the Germans have any equivalent to the US ROTC system between the wars, where as I understand it, many universities required their male undergraduates to participate, thereby producing a vast stream of at-least-partly trained junior officers? I just don’t know, skool me.

I ask because senior officers and the staff cadre plan battles, but NCOs and subalterns fight them.

A follow-up question concerns the nature of infantry training – it’s my belief that training for US forces placed the junior officers far-more among the enlisted/other ranks than any other army – while the divide between officer and enlisted was maintained, they all trained together in a way that was only seen in elite and specialized units in eg the UK and German armies, where the day-to-day training was entirely handled by NCOs. The result being that when the chips were down, US troops were being led by subalterns that they knew and understood, whereas others were maybe being led by officers they had seldom experienced in person.

Thoughts?

llater,

llamas

What is most remarkable in today’s Europe is the near complete eclipse of the German military. During most of WW2 the Whermacht retained a remarkable ability at the small unit level to hold its own against huge odds, this was especially so on the Eastern front and during the defensive actions in Italy, actions that for those who study such things were outstanding accomplishments of military skill and personal valour. This capacity, known to living memory, appears to have vanished, indeed apart from small entities like GS9, Germany has little stomach for any sort of rigourous military training or venture. Ironically this will change as civil conflict starts to consume Europe, as it will in the coming two to three decades.

The point about German combat superiority being due to their General Staff system may be partly true, but there are other factors.

First of all there is the fact that the Germans in both wars had better officers, this was because they had more of them. I think that the ratio of enlisted to officers in 1914 was about twice that of the French or British. This gave the Germans a deeper ‘pool” from which to promote their senior officers.

Second and more important is that by the end of WW 1 and throughout WW 2 the Germans almost always had firepower superiority in any infantry engagement. This was due to their use of multi purpose machine guns (MPMG) instead of automatic rifles. A British or American squad with one Bren gun or one BAR could normally fire half as many bullets in the first moments of an engagement as could a German Squad with an MG 38 or later an MG 42.

Late in the war in 1944 and 1945 the Americans and the Brits tried to compensate by distributing BARs and Brens more widely and i the US case by developing a MPMG version of the Browning .30 LMG.

The fact is that the Germans properly analyzed the effects of automatic fire at the micro tactical level while the US and the UK held on to the idea of the trained individual rifleman.

“I’d say, if you took the period Overlord on, the US Army wiped the floor with the Brits.”

Apparently, the Brits spent most of their time drinking tea and eating sandwiches during WW2 – when not ineffectually bombing innocent German civilians.

llamas:

In the Canadian army, officers from Captain down train shoulder-to-shoulder with NCMs, and have since at least WWI. I don’t know if that’s a practice we picked up from the Americans. I had always assumed that all the NATO armies did the same, but I never trained with any of the others so I don’t actually know.

Llamas

I don’t recall Dupuy having much to say about other ranks other than (by implication) that they were better than their opponents and the General Staff made strenuous efforts to spread information and learning and the doctrine of initiative far and wide.

I suspect that before either of the world wars it was difficult for a German undergraduate to avoid some form of military training.

On the question of officers training with men again he says nothing specific. My understanding is that prior to the First World War it was very difficult for a non-aristocrat to become an officer – which implies quite a divide between officers and men which I presume would be carried on to training.

It might be worth sharing Dupuy’s scores.

First World War. Score Effectiveness v. Germans

France 1.54

UK 1.45

US 1.02

The US’s score is low because it is based on the Meuse-Argonne offensive on September-October 1918, a time when the Germans were starting to crumble.

Second World War. Average Combat Effectiveness

UK 68.59%

US 70.06%

German 84.36%

Please don’t ask me what these stats actually mean or how they are calculated; I don’t know.

Dear Mr. Crozier:

For further reading, I would suggest Max Hastings’ Overlord, which deals with the performance of the German Army during the Normandy campaign. It reads like a case study of Colonel Dupuis’ thesis.

Taylor

I am very surprised to hear that the Germans had more officers. I had rather thought it was the opposite.

Sure the MG34 is a great weapon but who recognised it as such? I suspect the General Staff had at least something to do with its adoption. And it doesn’t stop with the MG34. Helmets, MP43, grenades, most tanks were all excellent pieces of kit.

There was also German technology. They had the best light and heavy machine guns, the best tanks and the best tank killers. Their aircraft were uniformly good, especially the fighters but laked a real heavy bomber. If they had had the V weapons earlier and their jets they might have won. Technology does matter. the Germans had the first assault rifle, but not enough of them. If you have superior arms you have high morale. Look what the tank achieved for the British in WWI. Again, superior technology.

It was said (Eisenhower?) that the Canadians were the best ally army man for man.

Does Dupuy address this?

‘fraid not.

Except I do not think it proved even slightly that “if you have air superiority, you don’t need tanks” 😉 I am inclined more to a remark I have read several Israeli officer quip… “typically it is the guy in the tank who wins”.

Removing the other guy’s tanks from the air does not mean you do not need your own… and even with air supremacy (not mere air superiority) there were numerous tank-on-tank battles in Iraq I & II.

Dupuy’s derived ‘CEV’ (combat effectiveness variable) is not about technology however. Indeed he points out in one of his books (“Numbers, Prediction and War” perhaps, I do not have it to hand) that if Egypt and Syria had swapped equipment with Israel, Israel would still have defeated them in all their wars, because of the very large CEV advantage. It does not mean technology does not matter, but Israeli, and indeed WW2 German institutional military ‘quality’ is not a matter of technology, it is a matter of organisational cultural factors. Indeed when you factor in equipment and technology and see what actually happened, the CEV is the emergent number to describe consistent deviations in ‘expected’ results “all things being equal”. Hense German WW2 superiority is seen in attack, defence, when they won and when they lost. Ditto Israel. Crudely stated, this was how Dupuy quantified multi-generational who-is-better-that-who on a pure ‘quality’ basis. Indeed using Dupuy’s methodology was by far the closest predictions how Gulf War I was going to turn out (with more conventional military pundits like Edward Luttwak predicting a disaster for the US of Kursk-like magnitude, where as Dupuy’s groupies were pretty much all saying “Nah, Saddam will get totally smoked by a huge margin”).

Many professional military simulation modellers loath Dupuy because he did not give a damn about mathematical purity, he was just a ‘pattern matcher’. Plus he was generally correct, so of course he was hated by his peers 😀

The fact the Germans in WW2 lost (and indeed Israel did not win every battle it fought) was because their enemies amassed enough of a numerical, logistic or material (or indeed technological) advantage to defeat them regardless of their qualitative edge.

@llamas (Do you pronounce with the “y” or the English “L”?)

Steven Bull’s “Second World War Infantry Tactics” indicates the Wehrmacht trained & encouraged soldiers to perform at a rank at least a couple above their nominal when required. That’s from pre-war training manuals, from which he quotes translations. The US Army based a lot of its training on translations of the same manuals. Ironically, the manuals themselves drew on work coming out of the British Army. Not saying the Brit officer class, itself, took much notice. It was the Brits who first worked the problem of combining infantry & armour for maximum effect. And infantry & armour practised combined tactics before the D-day landings. Yet the units who’d trained together & perfected the coordination were deployed separately & in different sectors for Normandy. Hence possibly Kurt Meyer, who commanded the Waffen SS at Caen to Falais, repeatedly expressing his amazement at the inability of the British & Canadian to exploit their vast superiority of numbers, material & air support against depleted & ragged defence, in his memoir. And his pride in his own men’s ability to keep fighting effectively after having lost most of their officers & NCOs.

Does he include civilian losses? – after all, a soldier is just a civilian in fancy dress.

The reason for the success of the german army was they had many fewer commissioned idiots, a company being a lieutenants commandant most rifle platoons were ran by sergeants.

@ DICK R,

Is that the case? Someone was arguing the opposite up above. I’d like to see the numbers on comparative officers.

Patrick

The pre 1914 German army had very large numbers of reserve officers. In German society it was socially important for everyone who could, to try and get himself a reserve commission.

In France however, due to a number of factors including the Dryfus Affair, the Governments made an effort to limit the number officers in order to try and keep as many fervent Catholics as possible away from positions of authority.

The General Staff was essentially an Operational element. It was the weapons people who did the analysis and went with the MG. It was not just that the MG 34 (Thanks for the correction) was an excellent weapon, based on a Swiss design, but that they made in the tactical centerpiece of their small infantry units.

Dr. Evil

The Germans never came up with a heavy machine gun to match the US .50 caliber. The Panther was indeed an excellent tank. The Tiger was powerful, but unreliable and lacked operational mobility. They also never had the ability to make enough tanks. Their Tank Hunters were good, but never matched their tanks, but due to vehicle shortages they had to use them as Tanks.

The US, in theory, kept it’s Tank Destroyers in reserve to deal with breakthroughs.

The Germans also never were able to make enough trucks to support their armies and depended largely on rail for their logistics, they were good at it but in the end they lost the ability to support their armies using the railroads.

Perry. You have to ask what a tank does. It’s simply a way of putting a high velocity gun onto a battlefield & having it survive there. It’s nothing more than a mobile pill-box. The concept’s WW1. Or before. It belongs with the dreadnought. If you don’t need to put the gun on the battlefield – & a gun’s simply a way of delivering destruction at a distance – why the tank?

The Israelis weren’t facing fast jets, modern ordnance & laser TI’s. To which they’re just a large target. Armed drones loitering above battlefields are the final straw.

Both Iraq conflicts had tank on tank battles because the Coalition wasted a great deal of time & energy shipping tanks. What were their armies supposed to do, having convinced their governments to spend a great deal of money on buying them for them? And cavalry officers must have their chance at the show or how do you justify all those horses. And uniforms with breastplates & white gauntlets. (Brit thing, isn’t it. Don’t think the Yanks are that class conscious, are they?)

Is any major power still designing & building tanks?

JohnW:

No, his works are entirely about battlefield success.

DICK R:

No that was not his conclusion at all. The TL:DR version: it was the German General Staff system.

The ‘commissioned idiots’ trope is largely a fiction as at lower levels, everyone’s idiots largely cancel out. And idiots at company level are less disastrous than idiots at brigade, division or corps: they are the people who decide if a battalion or company is in the right or wrong place to make a difference. That said I know an Israeli colonel (who is a Dupuy devotee btw) who does think the problem endemic in all Arab armies is that each command tier stops the two below them actually doing their jobs, from the Minister of Defence all the way down to sergeants. Make of that what you will.

Bloke in Spain,

I’m no military man, but it seems you are forgetting the other aspects of a tank: a whomping big pile of armor that’s resistant to small arms fire, and that it’s much easier and cheaper to stay on station than aerial units.

Stepping aside from military issues, this reminds me of The Xenophobes’ Guide to the Dutch. Unfortunately i cannot find my copy, but there is a quote to the effect that the Dutch combine what might seem incompatible: German efficiency and Anglo-Saxon flexibility.

Dupoy’s thesis seems to be that the Germans themselves, at their best, can combine their efficiency with Anglo-Saxon flexibility.

Yes. Russia.

Fascinating, learning new things. Thank you, BiS, Amazon, here I come.

The Germans had consistently, the best materiel in WW2 – when measured by peacetime standards of performance. It was the best-designed, the best-manufactured, and the best-performing. But all that best-ness repeatedly led to a weapon that was best weapon in its class, but a lousy weapon in war.

The Tiger tank is a prime example. A fearsome weapon, both in attack and defence, with far-and-away the most effective gun of the war and stunningly-good armour for the era.

But so big and heavy that it was hard to move anywhere, it was always limited because there was so much terrain that just would not support it. Its weight made it somewhat-delicate because the engine and transmissions had to work so very hard to move it in combat conditions. Extraordinarily-hard to repair in the field. And a voracious consumer of fuel – especially on the Ostfront, where it had to be run constantly just to keep the engine and transmissions from freezing. There was also the economic aspect – it cost so much to build, and tied up so many resources, that there were never enough, and all those resources could very well have been used to make weapons that weren’t quite so exquisite, but which would have the advantage of being available when needed. In truth, the full capacity of the Tiger was very-seldom required on the battlefield, which means that most of the time, it was a waste of resources. A great tank – a lousy weapon. The Russians were smart enough to build the T34, which was a pretty-good tank, and also dirt-cheap to make by comparison – which means they could flood the battlefield with them. Sure, if they met a Tiger, the odds were against them – but there were so few Tigers, and so many of (everything else) that their overall effectiveness was very high. The German tank wins at the individual tank-to-tank level – the Russian tank wins at the battlefield level.

Same with the MG34/42. I have shot both. They are a laugh riot, more fun that a carful of monkeys – as long as somebody else is footing the bill. But the MG34 is built like a Swiss watch – no surprise there – and so cost far more than an squad MG needs to (see Tiger tank, above) and the MG42 has such a prodigious rate of fire that it takes a couple of ammunition passers just to keep up with it. Both superb weapons by the specifications, built wonderfully-well, rugged, reliable, an infantryman’s dream – and a lousy weapon in battle. 1200 rounds per minute is an insane rate of fire for a squad MG, 3x what is required, but every single cartridge has to be made, shipped, hauled and loaded, and the gun wears out at 3x the rate of its more-pedestrian counterparts.

Brownings, by contrast, were built just-good-enough and no more, and they shoot just fast enough and no more, and with the advantage of the US production leviathan behind them, could be built in such prodigious numbers as to swamp any possible battlefield advantage that the MG34/42 might possess. The German gun wins at the small-unit level – the American gun wins at the battlefield level.

And so on. The Germans never developed any meaningful aircraft for the CAS role, which meant that they had absolutely no way to stem the Allied invasions of Italy or Normandy at more than a few miles depth. The Allies, by contrast, had some absolutely awesome CAS aircraft, which allowed them to devastate the German resistance in depth, and wreck their supply lines 100, 150, 200 miles behind the front.

The Normandy invasion was a classic example. Just five or ten miles behind the front lines, the Allies were moving unimaginable amounts of materiel onshore, through harbour systems put in place in days, virtually-unmolested by any German air power. On the other side of the lines, the Allied air power was just kicking the living snot out of the German defenders, from the front lines all the way to railway yards 200 miles and more back. You couldn’t move so much as a Volksturmmer on a bicycle down a Normandy side road without attracting the attention of a P47 or Typhoon packing the equivalent of a destroyer’s broadside, plus a hundred cannon shells, followed by about a thousand rounds of 50 caliber, mixed. Again – great German aircraft, consistently the best of the war at least until 1943 – but poor weapons.

Fascinating how counter-intuitive some of this stuff can be.

llater,

llamas

For the US and only the US, there were two wars. I am not suggesting that there was no allied help. There was but the numbers were very small.

The one written about here is on the European continent.

The other war was the Pacific War where it was two Navies fighting and amphibious landings. That was totally different. If you looked at the number killed then for the US, we lost the same number each conflict. Over 4,000,000 served in the US navy in the war, almost all of it in the Pacific theatre.

The point of this is that our equipment needs were split. For instance at the end of the war we had produced:

(56) Aircraft Carriers

(37) Battleships

(113) Cruisers

(1,050) Destroyers

(2,000) Support and Amphibious Ships

(334) Submarines

(40,000) Naval aircraft

Let that sink in. In addition, Harry Hopkins, FDR’s right hand man took a great deal of our stuff and it sent to the Soviets. Why? He was a Communist/Useful Idiot. Read Diana West for confirmation on that.

Always seemed to me the Germans fought both wars the way they wanted to, not the way they had to. Other than being a good loser I’m not sure what recommends that kind of thinking.

To say, or even imply, that North Vietnam won a military victory over the United States is false – their victory was in Washington D.C. (and in American universities and media circles before this) it has nothing to do with military matters.

However, that is a side point – Patrick’s main point is sound.

The German army was tactically far more flexible than its foes – right down to the private soldier.

Contrary to the stereotype of the “Prussian” the ordinary German soldier was encouraged to think for himself and given a greater latitude to achieve objectives than was the British or French solider (let alone the Russian one).

For example the British army imitated what it THOUGHT was the German system – not what was actually the German system.

The British army ideal of the private soldier (and even NCOs and junior officers) as robots was what they believed (what they thought) the Germans did – not what the Germans actually did.

It was not a lack of courage – marching slowly, in neat lines – “as if on parade”, into the face of enemy fire (into certain death – KNOWING they marched to certain death) requires great courage, and British soldiers did it in many battles.

Nor it is a question of intelligence or education – many great intellects died or were wounded in the British and French armies.

Men who had shown outstanding promise as poets, economists, artists – and so on.

It was a different military system.

Even in the Second World War British soldiers who were separated from their command would often sit about (or walk aimlessly) confused and inactive.

It was not lack of courage – such men were prepared to defend or attack to-the-death if ordered to do so.

But they had no “mission command” – the idea of “our mission is …. how am I to achieve it?” was alien to them.

Apart from in special units – such as the commandos.

In a sense (to a limited degree) all German soldiers were like British commandos – because they were encouraged (trained) to think for themselves.

German units often had to be “destroyed” repeatedly.

A British unit that was defeated was “destroyed” – in that the men would often (not always) sit or walk about till the got orders – even if the order was “for you, Tommy, the war is over – you must now come with me”.

German units, even if all the officers had been killed, would sometimes “reform” and fight again.

Even as late as 1944 German units that had been “destroyed” came back and attacked – British and American forces thought they were facing new German units – when they were actually facing ones they thought they had already destroyed.

Even German NCOs were trained to think in terms of the objective – and their thoughts were about how to achieve the objective.

But, but, but, but……..

The German individualism was TACTICAL not “strategic” (not political).

British or French or American soldiers could think anything they liked about political matters.

German soldiers, especially in the Second World War, could not.

Their “freedom” was strictly tactical.

“What is the best way to achieve X”.

Not “Is X a good thing to achieve”

Indeed popular German philosophy (even in the First World War) denied there was any such thing as objective principles of moral right and wrong.

This is not some theoretical point.

It means that (to someone who accepts this philosophy) the statement “we must not do is, because it an EVIL thing to do” is meaningless.

Or, rather, all the statement means is “to do this is boo (expression of emotive disapproval)”.

This sort of thinking was present in British and American philosophy also – after all Thomas Hobbes and David Hume was not German thinkers, but it had not become dominant.

In German elite circles (indeed by the First World War) it had become dominant.

This led to a savage combination.

A War Machine in the Second World War that was not just “free to think tactically” but also “free from the moral chains of right and wrong”.

Not a “freedom” to be praised.

And, again, the roots of this can be seen in the First World War (and before it).

The continuity in ideas between the German government of General Lundendorff (not just in economic management, his “War Socialism” – but in basic philosophy) and National Socialist Germany is only two real.

Even in 1914 the President of France (a philosopher) rightly declared the German Declaration of War not just a declaration of war upon France, but also (and far more importantly) a declaration of war upon the “universal principles of reason and justice” themselves.

He said that with very good reason – not just because the German Declaration of War was a pack of lies (it has the French bombing Bavaria and so on), but because he knew that the German elite (political and academic) rejected the very idea of universal principles of reason and justice.

I know your eyes are glazing over.

Or you are thinking of the various crimes and corruptions of various British, French and American leaders.

But this is to miss the point.

The point is a very basic one – but I sometimes despair of explaining it to certain people.

If a leading group (a ruling group) reject the very idea that there even are universal principles of reason and justice – they are capable of anything. Not just “capable” – it will happen.

Evil does not sit doing nothing, evil (in all of us) is active – seeking the first chance it can get.

Undermine resistance to evil – tell people that they can not resist evil (that their reason is just a “whore”, Martin Luther, or a “slave of the passions”, David Hume) or that evil is just “boo-hiss” (that evil has no real existence) and it is not a matter of “bad things might happen”.

Bad things will happen – very bad things.

And the “tactical freedom” (which was actually GREATER in the S.S. than in the regular German army) will be a deadly force.

This is not to say that tactical freedom is a bad thing – on the contrary, it should be encouraged.

But NOT the “freedom” from the “moral chains” of moral right and moral wrong.

Just in case someone does want to discuss military matters in Indochina – I am at your disposal.

I do not go into these matters because they are not directly relevant to Patrick’s post.

It is not what the post was really about.

The British army was never designed to fight mass continental wars it was until 1914 an imperial police force , very efficient at pouring volley fire into masses of third world spear wielding warriors ,but was found to be sadly lacking in training and equipment when faced with the Boers in south Africa and later the Germans ,their infantry possessed puny firepower ,with virtually no machine guns , believing niavely that dug in European troops would by inconvenienced by frontal bayonet charges led by pistol waving subalterns after having a few shrapnel shells explode over their heads .

Most of the British army commanders had no idea how to command formations larger than a few battalions and a cavalry regiment before the outbreak of the great war and found themselves totally out of their depth

Dupuy and what the numbers tell us about the typical quality of various national armies, the surprisingly quantifiable effects of surprise and tactical blunders, and what applications of airpower actually mattered blow up a lot of anecdotal based views on the subject. I recommend Numbers, Prediction and War and Attrition if you are curious about his methodology. Even Dupuy did not like some of his own conclusions 😀

I find it interesting that the Germans encouraged individual initiative in their army but not their society. The British founded their society on individual initiative but believed the army was s special case. The Germans ended up with the better army and the British with the better society.

Though one underestimated factor is that the German general staff had choice from the best people of each generation, which it seems the British armed forces never had. There is – and was – no high status, well paid career route for a young Oxbridge graduate in military science, unlike economic science or law. In imperial Germany, there was.

Britain’s Heath Robinson army matching the large French conscript army in WWI is BTW unexpected, were the playing field truly level. Seems like the French consistently underperformed.

I rread a book quite some toime ago by one of the Americans who was responsible for introducing their “shake and bake” NCO courses during Vietnam.

Im afraid the name of the bloke and the book have been lost to time for me but it fitted in well with a lot of peoples observations here. He instituted the courses not because it was what he wanted, but because thats all he could do.

Even that limited level of instruction to teach NCO’s how to be effective in making decisions/leading men caused a drop off in American casualties and increase in effectiveness.

I seem to remember one of his observations was WW2 had been careful to train its NCO’s well but that was lost after Korea and it took 1/2 of Vietnam to re-learn it.

NCO Candidate Course[edit]

Beginning in 1967 at Fort Benning, Georgia, the US Army Non-commissioned Officer Candidate Course (NCOCC) was a Vietnam-war era program developed to alleviate shortages of enlisted leaders at squad and platoon level assignments, training enlisted personnel to assume jobs as squad leaders in combat.[11]

Based loosely on the Officer Candidate School (OCS), NCOC was a new concept (at the time) where high performing trainees attending basic infantry combat training were nominated to attend a 2-phased course of focused instruction on jungle warfare, and included a hands-on portion of intense training, promotion to sergeant, and then a 12-week assignment leading trainees going through advanced training.[12]

Regular Army soldiers who had received their promotion through traditional methods (and others) used derisive terms for these draftees (typically)[13] who were promoted quicker, such as “Instant NCOs, Shake ‘n’ Bake and ‘Whip n’ Chills.'[14][15]

The program proved to be so successful that as the war began to wind down they elected to institutionalize training non-commissioned officers and created the NCO Education System (NCOES), which was based around the NCO Candidate Course. NCO Candidate course generally ended in May 1971.[

Paul, the topic in general is not in my area of expertise (is it spelt “millitarry” or “millittary”? *g*).

However, I was going to have to hold up the side by pointing out the truth about who won the military part of the V-N war.

Thanks for saving me the trouble. 🙂

The main reason for the effectiveness of the German military was their principle of mission-type tactics (Auftragstaktik). The German military would give their subordinates the mission, but it was up to them to figure out how to do it. This gave them a great deal of flexibility to adapt to local circumstances and allowed them to repeatedly gain the initiative against their enemies. In contrast, other militaries typically gave specific orders to varying degrees of detail that had to be carried out as instructed.

On reason the Germans could do this is that their junior officers were extremely well trained in comparison to their enemies. I read somewhere that the typical German NCO (corporal or sergeant) was equivalent to a Western junior officer (lieutenant or captain). This had much to do with the lack of militarization of Western democracies, and how much knowledge could be imparted on officer and troops recruited from peacetime with no previous military knowledge and had to enter the war immediately. I believe General Marshall as commandant of the US Army Infantry School had the school teach only one maneuver (the hook).

Does Dupuy give a timeline for the rate of attrition?

I would imagine that peaceful trading nations which had been proclaiming the benefits of peace and goodwill to all for centuries would be highly susceptible – initially – to unprovoked assaults from those nations who asserted otherwise.

One important German weakness that never gets mentioned is their poor medical service and their lack of even elementary field hygiene and sanitation. Some historians claim that this was due to the Nazi belief that their men were so racially superior that they didn’t need to take basic precautions.

In the 1940 campaign this did not matter but in Russia and in North Africa this failure insured that German units fought most of the time at half strength or sometimes less.

The British Army no doubt had its flaws, but it knew how to take care of its men’s health. All of those colonial wars taught them how to keep troops healthy in all sorts of extreme condition. British blood transfusion units for example were in advance of those in any other army, including the US Army.

But the fact is that the Germans were inferior in this respect, not only to the British and the Americans, but to their Italian and Japanese allies as well.

Taylor

Ive never read anything touching on German medical services, Im shocked if they were that bad.

Though I suppose the lack of tropical colonies might have contributed to a lack of good craft in this area?

Any links to info on this?

I read somewhere that the Germans also tried to keep locals together, so they were friends to begin with, when they enlisted. That could be another morale factor.

As for warcraft of the future, here’s an idea- The Solar Impulse is still flying. This is a solar-powered aircraft with one pilot, which flies day and night. That got me thinking- we’re also developing super-capacitors. I think the dirigible will return, but as a hot-air ship! With solar panels on the top and sides for power, and without needing Helium or Hydrogen, it would not need special ports, and could land anywhere! The Solar-powered hot-air air ship (Solairship) might be the ultimate aircraft carrier, or mobile drone base.

Any discussion?

An analysis of the “how and why” the Germans managed to fight so far above their weight class in both of the World Wars is difficult to fit into a small enough space to fit in this format. I’ve been fascinated by this subject since I first read Dupuy back in the 1980s, and have researched it to a depth most casual people won’t bother with. As a serving professional soldier, I thought then, and still believe, that there is a lot to be learned and emulated in what the Germans did. Of course, there’s also about as much to look at with horror, and studiously avoid, because as with all geniuses, they were horribly, horribly flawed.

Regardless of how you analyze it, or parse the numbers, the Germans did far better than they should have, in both wars. In some cases, the loss ratios were as high as 20 to 1, which is almost historically unique. How did they do it? What were the secrets? And, how on God’s good earth did we manage to beat them, with all they had going for them?

Firstly, you have to understand that the German military was superior only in certain specific areas. Strategic planning, industrial mobilization, and logistics were not their strong points, and can easily be argued as being why they lost the war. Operational art, and tactics? The Germans were superior to almost every Allied force, and were only defeated in these areas because of failures in the first three. Had the Germans had Allied resources and logistics, we’d all be speaking German today. Of course, they’d also need to lose Hitler and Nazism, and once you’ve done that, bang, zoom–There goes the whole war, anyway, and “They wouldn’t be the Germans, anymore…”.

There have been several references to things the Germans did better–Machine guns, tactics, and so forth. The key takeaway, however, is that the German Army was, in its essence, a learning organization. The Storm Troop tactics that came out of WWI? Those weren’t German, initially–They were written up by a French Captain, and a copy of his pamphlet with the proposed tactics was captured on a trench raid by the Germans. The French Army didn’t implement those tactics, but the Germans sure as hell did. And, interestingly, it wasn’t from a top-down basis, initially. The Germans who captured that pamphlet read it, digested it, tried out the techniques laid out in it, and found they worked. From there, the successful tactical system went up the chain of command, was integrated with the artillery tactics of Hutier, and there we have the genesis of modern tactical practice. That illustrates the key difference between the Germans and everybody else: When a French Captain developed and proposed new tactics, he was ignored. A German officer finds his pamphlet, puts the ideas into action, and the entire German Army gets a new way of doing things, that kept right on going until the final dissolution of the German Army in WWII.

That’s the key difference, the lightning in a bottle, that made the German Army so much more effective.

The Germans were also far more clear-eyed about a number of things. One detail about the machine guns that an earlier poster completely misses is the fact that the high rate of fire for the MG34/42 was a deliberate design feature, and for good reason: Without that high rate of fire, you cannot effectively engage small groups of men running from cover to cover at max range. You’ve only got seconds to identify them, and bring fire onto them; with the typical Allied MG, your rate of fire is around 600 rounds per minute. So, figure ten rounds per second you fire. If you drop multiple bursts into the beaten zone through which the enemy is moving, you’re only going to be able to actually deliver a scant few rounds into that area that the enemy squad is moving through. Now, try that exercise with a 1200 round per minute MG42: You are going to double the amount of rounds impacting that beaten zone, and likely kill quite a few more men in that squad. That was the point of that “extreme” rate of fire, and the “excessive” accuracy built into the German MGs–Something that most Allied analysts and leaders never grasped. Just like all the “overly elaborate” accessory items the Germans provided their gun crews–Periscopic sights, which allowed the gunner’s head to get down below the line of the barrel, making it much harder to kill him. Elaborate tripods, with built-in randomizers to help spread the cone of fire for close-in use, so that those “excessively accurate and extremely high rate of fire” guns could engage close in targets with equal effectiveness. The Germans built their squad and platoon tactics around crew-served weapons, thinking that it was more important to maneuver fires and weapons than men. The Allies used their MGs as support weapons, with their riflemen doing all the work. The Germans felt that the MG was the main point, and that the rifleman existed to help move, secure, and haul ammo for it.

Typically, the Germans would approach an attack on an allied position as an exercise to get the MG teams in on flanks or the rear of it, in order to make its continued occupation untenable. A direct attack, as most Allied leaders would call for, was anathema for the Germans; you might get yourself court-martialed for losing men unnecessarily if you ordered one, especially if there were time and terrain that allowed another, more economical approach. At the ground level, Germans depended on indirect means, while the Allies were more “Hey-diddle-diddle, straight down the middle…”.

Fortunately for us, the Germans were as stupid on the strategic and industrial level as we were on the tactical and operational. I could go on for hours, quite literally, with point after point after point illustrating this, but I’ll refrain. So, I’ll leave it at this.

Frollick

One source you might want to look at is ‘A History of Military Medicine” vol 2 by Richard Gabriel and Karen Metz

Taylor

I went over to amazon, read the review and thopught, “looks good i might grab it”

…

Holy snapping duckshit batman!!!!

2 Used from $891.06

Are printed on the skins of Amazonian children or something?

That *is* what the numbers indicate. The reason I liked Dupuy is it strips out so much of the bullshit from military analysis and just lays out the numbers for what happened.

Except that Dupuy’s methods and conclusions are massively flawed. He just gave the Germans an arbitrary bonus that he appears to pull out of thin air. He neglects the fact that the Germans, in both World Wars, failed to include the lightly-wounded, whereas the British (for example) included every scratch. In Crete for example the Germans suffered 4000 dead and 2000 seriously wounded, but there are no records of how many other wounded there were. IIRC there is also a case in Italy where he claimed that a British unit suffered about 1000 casualties, whereas the real figure was about 150. Dupuy also seems to have swallowed the myth that the Germans were inflicting casualties on the Soviets at rates of 5:1 or 6:1 or whatever. Simple demographics show that this is not possible. The USSR had less than twice the population of Germany plus Austria. Even if you allow that the Soviets had a somewhat younger population on average, there’s no way they could have had the kind of numerical superiority required for such kill-ratios. Given the massive losses the Soviets suffered in the first few months of Barbarossa, it’s likely that the actual German kill-ratio for the rest of the war was roughly 1:1.

It’s easy to look good when someone’s fiddling the figures for you.

Incorrect. The CEV was calculated retrospectively after factoring out material and positional factors and seeing if there is a persistent discrepancy in advance rates and casualties.

@Kirk – continually-fascinating. Thank you.

I may not have made my point about the MG34/42 very well.

I understand the purposes of the designs, which you described much-more-completely than I did. But two facts do remain, which are

– the situations you described, for which the MG34 and especially the MG42 were designed, were relatively-infrequent compared with (all the other battlefield situations into which they were thrust). And so many users were stuck with the high rates of fire, the very-frequent barrel changes required (no matter how quick-and-slick the barrel-change system is, and it is) and the logistical effort required to keep the gun fed and in barrels. One other shortcoming of the design was the difficulty of designing a variable rate system for it, something which they tried to do with the selective-fire trigger of the MG 34, but which was never satisfactorily addressed – so it was 1200 rpm, or nothing.

– The MG34 was built like a Swiss watch, and I’m not referring to the fire accuracy but to the manufacturing process. It was built to last forever, and it did. But the price they had to pay was that there were never enough. The MG34 was always in chronically-short supply, the MG42 helped somewhat with its cheaper manufacturing processes, but by then it was too late. It doesn’t matter how fine a weapon it was (and it was) if you don’t have one. And if your infantry tactics have the presence of these weapons as a significant part of the doctrine, then things go pear-shaped very quickly when the weapon is not there.

Air-cooled Brownings, by contrast, were cheap to make, easy to service and repair (a significant difference also, read Ernie Pyle’s account of small-arms being depot-rebuilt in Normandy within earshot of the front line) and quite good enough for almost-all infantry situations.

If you need to put a lot of rounds on a particular spot, you can do it with one MG42 in a high-precision mounting, or half-a-dozen M1919s resting on logs or rattling around in Jeep mounts. If your one, superb, MG42 is hit, or flanked, or quits – you are all done. Lose one of the economy Brownings, well, that’s too bad, but you still have 5 left.

Again, I’ve shot both, although not for real. The MG34 I shot was mounted in the Lafette mounting, a true work of art (I’m an engineer and I appreciate these things). They are awesome weapons, absolutely the finest of their generation and maybe ever since. Their shortcomings have little to do with their function as weapons, but everything to do with the 101 other things that make up the total solution.

If it’s me vs him, I’ll take the MG, thank you very much. If it’s my division vs his division in Normandy, or at the Rhine, with all the parameters that were in effect at the time – it’s the Browning, please.

It points up a fundamental difference in materiel doctrines. The German approach tended towards the idea of ‘the best possible design of materiel, made the best it can be made’, whereas the US approach was more often along the lines of ‘pretty-good stuff, made in vast quantities’. (We won’t address the British approach, which can be defined as ‘a random mixture of inspired designs and total crap, well-built but always too late’). And the US approach generally prevailed.

Your points about tactics and training are well-taken, these are areas about which I know little so appreciate the improved understanding.

llater,

llamas

I’ll ask again -Does Dupuy give a timeline for the rate of attrition?

I would imagine that peaceful trading nations which had been proclaiming the benefits of ‘peace and goodwill to all’ for centuries would be highly susceptible – initially – to unprovoked assaults from those nations who asserted otherwise.

So France and Poland – the closest non-aggressive countries would have the highest casualties.

How is this different from Sparta – who the Germans loved. A small bunch of war-loving nutters versus the Athenians.

I think, from what I have read, that mostly fighting units (as manpower) in both world wars were much the same, though some were more hampered by lack of equipment, failure of leadership at key times and — significantly in the second world war — the supply of fuel. There was even the factor that should the German army not recover their damaged tanks, they were at a disadvantage. This of course is true of all armies, but if the tanks were better on the German side then the disadvantage was probably greater.

But war is many things on many fronts, and so many factors come into play, even down to weather and location so that it is near impossible to evaluate it other than who eventually triumphs. For whatever reasons, Germany did not triumph in both major conflicts. I am sure you know this: it was in all the papers.

A small aside about the relative differences between British and US troops. I was talking to a guy who was in the British army for twenty-odd years and he said that most troops were much the same though of any allies he could choose, it would be Israeli soldiers. He had a very high opinion of them. Of the Americans, a little less so. He said he had been in the US on a combined exercise and his unit had to be ‘found’ by the US force opposing them. Well, his unit essentially hollowed out a bush and hid there and the it took the US forces quite while to locate them. Fair enough, but he said the key thing was that the US wanted to use firepower from a distance to ‘combat’ the hidden force and would not approach the hideout on foot. he thought that they weren’t happy about what isa basic element of infantry warfare, that of confrontation at close range.

As another aside, I was talking to a guy in the Territorial army who was very proud to have taken part in a bayonet charge against the taliban. As I say, at times it comes down to confrontation at close range. Something to do with having balls.

JohnW, your questions make no sense to me. Taking someone by strategic surprise has nothing to do with a nation being peaceful or aggressive in their underpinning institutions or culture: take for example Operation Barbarossa – two aggressive nations, one taking the other by strategic, operational and tactical surprise. It is about an intelligence and/or political failure to anticipate coming under attack.

Just pick up a copy of Attrition if you really want to understand his methodology. The effects of surprise on casualties rates and combat power are discussed at some length.

Taking a leaf out of Nelson’s book at Copenhagen, ‘I see no signal‘ when offered an opportunity to retreat by Admiral Hyde Parker.

JohnW, your questions make no sense to me… It is about an intelligence and/or political failure to anticipate coming under attack.

But that is precisely the point.

Patrick said ‘even when you remove[d] the Russian numbers Dupuy found that the Germans still held a clear and consistent superiority over the French, British and Americans. This superiority existed regardless of whether the engagement was offensive or defensive.’

What is the reason for the Western Allies “intelligence and/or political failure,” to use your words?

I still do not understand your question. The CEV (the ‘quality’ issue) is an observed multi generational factor and has nothing to do with taking people by surprise or indeed any transitory effects. So when you ask:

I do not understand what you mean. Yes, being taken by surprise – initially – leads to a spike in casualties and a marked diminution in combat power for a few very important days. But that has nothing to do directly with the ‘quality’ factor or political niceness, nor does it have baring in the attrition rates per day once the direct effects of surprise have worn off… which is why I am not clear what point you are trying to make.

Israel was taken by strategic, operational and tactical surprise in 1973 and the screening forces along the Bar Lev line and the operational reserve that was committed got their clocks cleaned by the Egyptian army as a result. But even there, the enormous qualitative advantage of the Israeli Army vs the Egyptian Army did not go away, it was just negated by a combination of surprise and sheer numbers. The daily rates of attrition during a battle are a consequence of the balance of effective forces in contact, modified by the situational factors such as posture, surprise and, of course, outcome. Attrition is modified by ‘quality’ (i.e. ‘culture’) in so far as ‘quality’ modifies combat power and therefore the end results of a clash.

I think JohnW is referring to wars that are either aggressive or defensive. Dupuy is referring to individual battles or engagements within those wars.

My point is this – a country with a “peace-mentality” does not necessarily provide the most fertile ground for excellent military ideas! When useful evidence is provided it is ignored, but once the situation becomes critical priorities can change.

The book seems interesting and mirrors similar developments in the air-war [finger fours] and anti-tank gun use [by the British v the Germans.]

John galt: I think your production numbers are a little off.

Battleships – 8 built (10 if you count the two which commissioned in early 1941 prior to US entry). There weren’t 37 Battleships built worldwide between 1939 and 1945, let alone by the US.

Aircraft Carriers – 24 Essex Class CV’s, 9 Independence Class light Carriers, 69 Escort carriers.

Bob Sykes:

Pretty much these days outside of a few scary SOF-type units the German army is a parking place for young people to make the government’s unemployment numbers look low. I doubt they would be more effective than any other European country in the event of a major war – the Prussian military culture which spawned the general staff that impresses Dupuy was thoroughly destroyed during (by Hitler) and after (by the allies) WW II.

You have to ask what a tank does.

Infantry support, every time. Without infantry around it, a tank is a waste of time. If you need to take ground, you need infantry. If they have armour in support, they will be far more likely to succeed.

Unfortunately i cannot find my copy, but there is a quote to the effect that the Dutch combine what might seem incompatible: German efficiency and Anglo-Saxon flexibility.

Interesting, because I reached much the same conclusion on my own.

@TimN

You have it exactly. A tank has no other purpose but infantry support. And without its supporting infantry, its extremely vulnerable to any opposition footslogger in a ditch, with a cheap tank killer.

So the question needs to be answered; what’s the most effective infantry support?

And “If you need to take ground..” is another.

You take ground to deny the ground to the opposition. But do you need infantry? A dumb minefield was a WW2 solution to occupying ground without using infantry to do it. (Although a dumb minefield, itself, needs to be defended. So it can be thought of as a force multiplier, rather than a complete solution)

But remote operated & autonomous vehicles/weapon systems may provide a way to deny ground without utilising much in the way of infantry. Or any at all.

So, like the tank, one needs to avoid being obsessed by how well it does what it does. And look at whether it needs doing in the first place.

Not sure if armies are too good at that. There’s too much invested in the status quo. It’s like formation marching. Looks pretty. It was originally developed to concentrate musketry fire. Infantry squares ‘n that.(And even before, pikemen) It definitely became suicidally obsolescent when the machine gun was developed. But they’re still marchin’…

I agree with BIS, and his key question is “do you need infantry?”. Remotely-controlled and “smart” weapons have largely eliminated the need for a large infantry (provided that one has access to such weaponry in sufficient quantity, of course). Ground troops will certainly be needed in almost any serious conflict, but for the most part they can be confined to special-forces troops having a very limited role. And that role will become even less important with continued advances in remotely controlled weaponry (i.e., battlefield robots). Unfortunately, BIS is correct that “there is too much invested in the status quo.” Generals always want the best and newest toys, even if they don’t really know how to use them to best advantage (it’s trite, but nonetheless true, that generals are always fighting the last war), and of course our munitions suppliers hold significant political power to ensure that the cash keeps flowing. So we end up maintaining a huge but unnecessary standing army and a procurement process which ensures that we get sub-optimal gear at premium prices, a decade too late. Such is life.

I think you leave one out of the vested interest triumvirate, Laird. The civil service. And there’s the fascinating shell game the three play out, serves that interest.

It starts with a “Strategic Defense Review” or whatever profound title is the flavour of the time. Some aspect of military capability is judged to be unaffordable or surplus to requirements. Regiments, squadrons, ships. At which the ” Great Traditions” of the affected Service & particular division of gets paraded, to enlist public support. A fudge is crafted. Often at the expense of capabilities that genuinely are needed, but aren’t so glamorous. Or so needful of expensive kit. Shuffle the cards & deal again.

It’s why conversations like this are so important.

What Great Traditions? Post Waterloo & Trafalgar, that is. Or maybe Agincourt.

Actually, the great traditions of the British military, since, largely consist of narrowly avoiding routs against all expectations. Dunkirk was not a victory. Nor was the Battle of Britain. It was a successful defense in a campaign of attrition. Different thing altogether. They didn’t lose.

I’m minded it would be damned good idea the abolish the British Army, the RAF & the Royal Navy, consign their battle honours to a skip & start again. A modern self defense force whose troops on the battlefield don’t have helicopters & air support under an entirely different command, simply because they claim jurisdiction over everything above head height. One that doesn’t have separate airforces because one lot has airfields that float. And most of all, because it wouldn’t require quite so many purported warriors fighting bitter campaigns over the territories of their desktops.

Maybe, then, they could work out what the hell they’re supposed to be doing.

Agreed, Bloke. I’ve long argued that we (in the US) should consolidate all of our various land, sea and air forces into a single “Military Service” under a unified command. And I would require that to achieve flag rank one must have had at least one command in each different type of unit. You can’t stop (and probably wouldn’t want to stop) a certain amount of inter-service rivalry among the line troops in those different divisions, but that rivalry should disappear at the senior officer level.

Adam Maas,

My point was that our equipment had to go to two entirely separate wars. In the American Japanese War in the Pacific our kill ratio was 10:1.

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/C/a/Casualties.htm

Your point might also be; the US launched two major invasions in a fortnight. 128,000 US troops began landing on Saipan, June 15 ’44. But they’d got the ball rolling with the side show in Normandy & a mere 88,000.

Laird: “we (in the US) should consolidate all of our various land, sea and air forces into a single “Military Service” under a unified command.”

I seem to recall your near-northern Neighbours tried that about thirty years ago.

How did that work out?………. Ay?

On a slightly different note:

The Germans wrote the book on machine-gun deployment, way back in WW1.

The classic study, at least from an Australian perspective, is the Battle of Frommelles, which saw a prodigious slaughter of young Australian troops. The (mostly) Bavarians, also deployed their guns in FRONT of their main fighting trenches, usually in tough little bunkers that were regularly upgraded and reinforced with steel, rock and concrete, often carried up close to the front by a clever little trench rail system.

Our Teutonic cousins had actually STUDIED what machine-gun fire actually DID on impact.

Even if the gun is locked off on its tripod, there will be “natural” dispersion. The area struck by the bullets is known as the “beaten Zone” and is, more or less, elliptical.

A GOOD MG plot involves from four to ten guns, each laying down these long ellipses of carnage, and with each zone overlapping the adjacent ones.

The guns are NOT swung wildly to and fro as per the movies, nor are they fired in LONG, barrel-destroying bursts.

One of the guns will be the sighting / ranging gun. It’s job is to fire short test bursts for observation and aim correction. We are talking here of laying down fire at 800 plus metres. With a decent cartridge like the 8mm German or .30-06, reaching out to 2000 metres is easily achievable. That the bullet may be subsonic at those extreme ranges is not really an issue; someone is “gonna get hurt”. Furthermore, and VERY importantly, the PSYCHOLOGICAL effect of bullets cracking or “buzzing” (subsonic) overhead tends to keep heads well down.

If your troops are groveling at the bottom of foxholes or trenches, they are not in a good position to detect and counter a possible ground assault.

Another thing is that dispersed MGs are sited and tasked such that each gun can fire DIRECTLY ON and around at least two other MG sites. Any attempt by opposing infantry to “take” one MG position, will bring down accurate, pre-registered fire from two or more other MGs.

The other feature of Fromelles (and several other engagements) was that many of the German machine-guns were deployed as far FORWARD as they could site them without detection. Their task was to fire ENFILADE along the long ranks of infantry struggling past, through the mud, shell-holes and barbed wire. And they did it over and over again: the slaughter at Fromelles was horrendous. Artillery was always seeking likely, (or actually observed) troops concentrating for an assault. Once that assault started, the machine-gunners and”mine-throwers” (crude mortars), did their worst.

I am interested that, in the blog posting and the whole of the comments above, no mention is made with respect to signals intelligence (sigint) for European and North African aspects of WW2.

Even though I understand that the analysis by Dupuy is primarily concerned with tactical combat performance, I would have thought the Allied advantage from cryptanalysis of German army and other high command and Abwehr communications would have had a substantial effect. Though this would presumably be mainly through advantage at the strategic level, by choosing engagements (and force mix where practical).

Does anyone have any more information on this, please?

Best regards

From memory – I recall the Germans trained thousands of signal corps staff prior to WW1 and WW2 in preparation for both wars, even while the Brits were still busily debating how they would NOT defend their own country under any circumstances.

Llamas:

Re the MG-34 and 42 (Hitler’s Zipper)

The Mg34 was, indeed, built like Swiss watch; its technical “genetics” might have quite bit to do with that.

The MG-42 is a different beast altogether; MUCH cheaper to manufacture in bulk, far superior barrel change system AND, the ability to alter the rate of fire by swapping out the buffer assembly. The very “modern” practice of “hammer-forging” barrels was developed to an art-form by our Teutonic cousins to keep up the required rate of barrel supply for these amazing machines.

If you are trying to hose aircraft out of the sky, you need a VERY high rate of fire in the hope that SOME bullets may hit.

If you are laying down a defensive fire plan, you can back off quite a bit.

The insane MAXIMUM rates of fire with an MG-42 are partly a result of the speed of the bolt-locking system. The bolt does not turn or tilt, it is quite fascinating to study the elegant, and simply constructed mechanism, both at rest or at “play”.

The MG-42 and its successor, the MG-3, are marvels of engineering, regardless of how fast you want to “rock and roll”.

Well the Wehrmacht weren’t always on top with their tactics, as ‘Ace’ Rimmer showed.

The entire discussion above is fascinating. One wonders what the ratings and results might have been like if the French and British had Panzer 4s & the Animal tanks but the Germans had the cruiser tanks & Char Bs. And what if the Americans didn’t have to design the Sherman with an eye towards ocean shipping (could put the much longer/better 3 inch antitank gun in it)? The good thing is that the Americans wound up the war with the Pershing and the Brits the Comet. I believe the Centurion was in existence also but the Germans finally had the good sense to call it a day. So maybe the scores would have been different if the pre-war infantry dominated services didn’t downplay the value of armor.

One subject not broached is the organization and weapons of the nasty old Waffen SS. While they might not be a good moral choice of subject, they were military innovators. The mixed arms (i.e.: tanks, grunts, arty etc. all under the same commander) concept they used helped to eliminate a great deal of the “military parochialism” that I saw weaken the US Army during my time (Vietnam era+) as a private thru captain. I’m not saying they invented it but they sure used it well

According MG (Retired, British Army) Mike Reynolds in “Steel Inferno”, (1st SS Panzer Corps in Normandy), the system worked well but they had a lot of casualties. No, I don’t know the numbers (can’t find the @#$% book right now). Many have emulated it since anyway. See 3rd ACR at 73 West, Iraq.

There is so much to comment on but I’m afraid I will misspeak. The things I remember from my time a potential casualty are the confidence sapping of the miserable first editions of the M16 rifle (it was only missing one cleaning brush for success) and that NCOs were and always will be the very heart and soul of any military unit. Oh yeah, and our artillery was outstanding.

Having really useable weapons is a good way to avoid casualties. Hope I didn’t drift too far.

As far as scores cards for wars are concerned, the only ones that actually count were turned in at Rheims, France and Tokyo Bay.

I’d say that the 1914 all volunteer British Army was superior to the German Army of the same date – just much, much smaller. Naturally, that changed over the course of the war as the professionals were diluted by amateurs and conscripts and the Army swelled massively in numbers.

By mid – 1918, the British had developed, and perfected, the ‘Combined Arms’ attack, with Tanks, Infantry, Artillery and Air all working together.