We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

I saw this by Alan Moore on the SMLXL blog, referring to the Communities Dominate Brands blog (Alan Moore is one of the co-authors of the book the blog refers to). We often hear about the economic impact of the internet, mobile communications and new media, but the real story is that it will change just about everything, including culture, politics and government.

There is a school of thought, that, within 10 years communities will have replaced the orthodoxies of government, management, business and marketing as the primary medium by which these organisations will successfully engage with their audiences.

Further, enabling or capturing peer-to-peer information flows will transform these organisations and how they engage with their stakeholders, simply for the better.

And, that those organisations that ignore the newly empowered and connected customer/voter/stakeholder will simply struggle to survive.

This is the unsung, un-remarked media and cultural revolution. That the great explosion is in peer-to-peer communication – something many organisations up until now have overlooked.

A few days ago, Findlay Dunachie died.

His widow Lyn asked us to send her a few words of appeciation concerning his contributions to Samizdata, and we sent her the following, some of which will be read out at Findlay’s funeral, which is to be held this coming Tuesday. These few hastily composed reflections were not written with a view to publication on Samizdata, but when we asked Lyn if she would object to them being used for this purpose also, she very kindly agreed.

Last night we at Samizdata received the sad news of the death of Findlay Dunachie. He had recently told us that he was, he believed, dying, so this was not a complete surprise. But we were still greatly saddened. Only one of our number ever actually met Findlay, and we know him best through many phone conversations, but above all through his writings for Samizdata. Selfishly, we regret that there will be no more such writings.

Samizdata is a weblog – “blog” for short – devoted to spreading news and comment, profundity and triviality, concerning human freedom, human progress, and about the many and various enemies of these things. We seek to celebrate and to spread the ideas of, approximately speaking, classical liberalism and libertarianism which Findlay Dunachie held dear.

For a number of years, Findlay had been writing review articles about some of the many books he had been reading, and in October 2003, having received a great trove of these writings, we at Samizdata began to publish them.

Almost all of Findlay’s writings for Samizdata were book reviews of one kind or another. In total we published just under fifty such articles, the most recent one being a timely tour de force about Nelson, the Battle of Trafalgar, about the man Nelson’s death left in command of his fleet, Admiral Collingwood, and about the aftermath and consequences of the battle.

Looking down the long list of topics covered, a few things stand out. Findlay wrote about the whole world and about the world’s long varied history. He did not confine himself to his own country or culture, or to his own time. However, a deep love of Britain, its language, its institutions, and of Britain’s on-the-whole beneficial and liberal effects upon the world is also strongly evident in Findlay’s writings, as is an interest in the various forces arrayed against such influences – continental European despotism, such as that against which Nelson fought, such as communism in it various forms, and such as the more repellent aspects of Islam throughout its long history.

Findlay’s professional background as a scientist was also reflected in his interest in the claims of, and the most scrupulous and eloquent critics of, the environmental movement, so much of which involves making misleading or false claims about science and about technology, and about the largely beneficial effects of technological progress.

From the start Findlay’s writings were hugely appreciated, by a readership concentrated in but by no means confined to Britain and the USA. We know this, because at Samizdata our readers are able to comment. And concerning Findlay’s many writings, comment they did, gratefully, effusively, and continuously. It was regularly said and never contested that Findlay’s reviews were among the best things if not the best things to be found on Samizdata. Since, on the whole, Findlay tried to read books that he himself would end up liking and mostly succeeded, he surely made a not insignificant contribution to their sales figures.

His widow Lyn tells us that it gave Findlay enormous pleasure to find readers for his writings at this late and presumably rather painful time in his life. The feeling, but not the pain, is entirely mutual. It gave us huge pleasure to have published Findlay’s writings.

Those of us who had direct dealings with Findlay, by phone or in person, formed the impression that he was, quite aside from being an attractive and formidable intellect, also a thoroughly nice man whom it would have been a great pleasure to have known a lot better than we did, and to learn a lot more of what else he did in his life besides write things for Samizdata. Geography made that difficult. But modern electronic communication, in the form of the internet, made it possible for Findlay to find readers who would otherwise never have encountered his mind and writings.

To all his closer and closest friends and loved ones we at Samizdata say: we hope and believe that we helped to make the last two years, for Findlay, that little bit better than they would otherwise have been. If so, this is only fair, because he did exactly the same, and more, for us and for many readers the world over.

After being to a wedding this weekend, I must confess that I have had enough of dealing with people for a little while. I am not the world’s greatest social butterfly.

Ann Althouse points to a classic article that helps for dealing with people like me, one that I deeply wish I could print out and send to most of my family members. I would highlight this passage in particular:

Introverts are not necessarily shy. Shy people are anxious or frightened or self-excoriating in social settings; introverts generally are not. Introverts are also not misanthropic, though some of us do go along with Sartre as far as to say “Hell is other people at breakfast.” Rather, introverts are people who find other people tiring.

Quite so. All things in moderation is my motto.

We can only dream that someday, when our condition is more widely understood, when perhaps an Introverts’ Rights movement has blossomed and borne fruit, it will not be impolite to say “I’m an introvert. You are a wonderful person and I like you. But now please shush.”

In Jonathan Pierce’s recent article about the British Crime Survey, many were questioning the validity of the data but the BCS has always struck me as one of the more reasonable surveys of this kind. I think one has to be very careful about drawing too many ‘obvious’ conclusions from the data (such as one commenter’s bizarre remark that declines are down to CCTV), but the data itself seems as good as one can reasonably expect.

For what it is worth, some years ago a fairly senior policeman with whom I was acquainted put it to me that the significant decline in burglary had nothing to do with CCTV or detection rates (which were actually declining) or convictions per crime (ditto) but rather that as items like computers, DVD players, CD players, CDs, microwaves, wristwatches and the like had now become so inexpensive compared to steadily rising national incomes that even in quite ‘deprived’ areas, the ‘economics of crime’ simply made that sort of offence hardly worth the effort and risk. Why buy a stolen DVD player from some thief when you can get a new one that is more likely to actually work for the relatively trivial sum of £100?

Make of that what you will.

Back in April, whilst delivering political leaflets is the pouring rain, I asked myself (not for the first time) “why do I do this?”

After all I do not hold some Conservative party policies in high regard – state pensions increases linked to the rise of average earnings, free higher education, bankrupt private pension funds bailed out with money found from “money forgotten about in banks” and so on.

Also I do not like some of the things that the leader of the Conservative party has been doing recently – getting rid of Conservative candidates because he does not like the (very mild) things they have said, or because they happen to have had their photograph taken where there were firearms (which did not belong to the candidate) also in the photograph.

Indeed Mr Howard recently got rid of a serving Conservative MP (Howard Flight) for saying he that he thought there was greater scope for savings in the government budget than the Conservative party was committed to (Mr Flight said nothing about “secret plans” and, as his remarks were recorded and published, Mr Howard knows he said nothing about “secret plans”).

So why was I getting soaked in the rain putting out leaflets? Well I quite like the people who are standing locally for the Conservative party (I would not like to see them upset – and they would be upset if they lost). But there is another factor – a bad conscience.

In 1989 (just as this year) there were County Council elections in Northamptonshire, and a person I knew and liked was in line to become the leader of Northamptonshire County Council.

Everybody told me that the lady was in a safe seat and that I need not concern myself with the campaign. And, besides I was off at university (anyway I was going to become a academic and was bored of my years of helping out with practical politics – if I had known what the future really held in store for me I would, if I had found the courage, taken my own life, but that is another story). So I contented myself with coming home for the day of the election and left it at that.

The lady lost by three votes and the Conservatives lost Northamptonshire Country Council by one seat.

The Labour party made much of the Conservatives losing Northamptonshire and it was one of the factors by which some Conservative MPs justified their attack on Mrs Thatcher in 1990 – an attack the Conservative party (and Britain in general) has never recovered from. I will never know whether Mrs Thatcher would have fallen anyway (wicked people can always find an excuse for their wickedness), but I did leave a local friend to lose.

So yes ordinary people “can make a difference”, I proved that by making a difference for the worse.

On a train from Manchester to Nottingham I was sitting at a table when I was joined (in Sheffield) by two academics from the University of Nottingham.

The two gentlemen talked (rather loudly) about the internal affairs of their department (which seemed to be a ‘social policy’ department, at least the term ‘social policy’ was used) and their nice trips to various European nations and to Australia, New Zealand and Japan.

What struck me was the total lack of interest in ideas that the academics showed – they both boasted of using the same talk again and again, and neither cared whether their talks represented the truth or made any contribution to knowledge.

I only spoke once. One of the academics was boasting of his trip to the “biggest city in New Zealand”, but could not remember the name of the place – so I told him it was called Auckland. But later he seemed to be under the impression that he was talking about the capital of New Zealand – so he may have meant Wellington.

For the rest of the time I just sat there in the hope that some sign of interest in ideas would be shown by either man, but it was not.

I remembered Professor R. of the Politics Department of the University of Nottingham. Professor R. had always been interested in ideas – although I can not say that I had always agreed with him.

Once at a conference in London I had expressed the fear that local councils would use the introduction of the Community Charge (the “Poll Tax”) as an opportunity to increase spending – and blame the bill on the new system (my own position was that a local sales tax would be the least bad option – as people could at least vote with their feet and shop in the cheapest areas thus, perhaps, forcing down the level of the tax).

Professor R. had replied that I was too cynical and that most politicians met well, they were just guided by mistake ideas. As my own view was that most politicians (and many other groups of people) were scum, our difference of opinion became quite sharp. Perhaps my anger was due to Professor R. reminding me of my father – a man who was betrayed so many times and yet maintained a strange (at least strange to me) faith in human beings.

Some years later (after some “modernization” of academic life) Professor R. killed himself.

As I have said he was man who was interested in ideas and valued them, but perhaps he had too much faith in human beings (just as, perhaps, I have too little faith in people).

I miss people like Professor R., they thought that other people were like themselves (and they are not), but the world would be a better place if they were correct and people (especially academics) were really honest and dedicated seekers after truth.

Still what would have I had heard had the two academics had been interested in ideas? The latest plan to reform the Welfare State – yet another pattern for the deckchairs on the Titanic?

Or (if the academics had been economists) the claim that the best way to promote prosperity was to “reduce interest rates and stimulate demand”.

I have even heard libertarians talking as if investment did not have to based on real savings ( fiat money and credit bubbles performing this function instead), and as if prosperity was based on consumption (rather than on work to produce goods and services of value to human beings). The madness of the boom bust cycle being presented as what “all serious economists” believe (as a columnist in the “Times” newspaper put it – referring to his idea that Germany’s economic situation could be improved by issuing more money “stimulating demand”).

What is worse? People who are not interested in ideas, or works of political philosophy, economics (and other subjects) that are filled with absurd nonsense and seeing this nonsense repeated in so many places, from leading universities to television and the newspapers?

One cannot say, in general, that there should be more

or less legislation: that is for governments to

decide. If the present volume of legislation is

causing problems at the various stages of the

legislative process – and all our evidence confirms

that this is so – the first requirement is not a

reduction in that volume, but improvements in the

process at those stages where it is under strain. The

kitchen should be big enough and properly equipped to

satisfy the legislative appetite.

– Making the Law, Hansard Society, 1993.

So much for separation of powers in the view of serious British parliamentarians.

I think it is a mistake to assume that the motivations of all people in government, or most of the people who vote for governments, is knowingly malevolent. Most people want to believe the policies they support are ‘helping people’ because voting or passing a law makes them feel good about themselves as they are ‘doing something’. Consequently such people really dislike having it pointed out that their ‘something’ actually makes things worse more often than not, regardless of what their motives are.

That said, I think there are indeed quite a few people who understand full well the real harmful consequences of what they do, and they do it anyway because all they care about is maintaining the political apparatus from which they benefit at the expense of others. Those people will also react angrily to this being pointed out, because what they do requires their motives to be thought of as benevolent by the wider public whereas in reality it is just a force backed appropriation that benefits a favoured constituency at the expense of those less favoured.

My view is that ‘doing something’ via the state is sometimes the correct thing in an emergency (most obviously during a war, plague or natural disaster). Alas people often then apply the same logic to normal civil society outside the context of the emergency, acting as if the social logic of the lifeboat and normal civil society were one and the same (libertarians of some ilk often make the same mistake but from the opposite direction). A leitmotif of the post war British election in 1945 was “Look what we achieved together in wartime, think what we can do in peacetime!”… as if life in a total war and life in the social context of peacetime were much the same thing. The same logic used when being threatened by a totalitarian state is then applied to the ebb and flow of normal social life generally with monstrous results.

But cynical politicians who know full well the real consequences of their actions have powerful reasons to misrepresent the truth bacause all they care about is maintaining their personal power and influence and they do this by playing to people’s need to feel good by ‘doing something’… and they are the people who will do it. For this reason I think it is very important to keep pointing out the true effects of actions that governments take, and the consequences of participating in a process designed to lead to those sorts of interventions in civil society. Sometimes it is important to make people feel bad about themselves for ‘doing something’.

There is an interesting article on American Thinker about the institutional mindset of political correctness.

A team of Indiana firefighters, volunteering to help rescue victims of Katrina, went to Atlanta, where Federal Emergency Management Agency staffers told them that their job was to hand out fliers and that their first task was to attend a multi-hour course on sexual harassment and equal employment opportunity

And a useful comment on that story that quotes Theodore Dalrymple can be found on No Pasaran

Today’s Guardian is as ever full of fascinations, but this, from a TV review by Mark Lawson struck me as gloriously, perplexingly weird:

The notable balance of the film is shown by the fact that both liberals and conservatives are offered a harrumph-moment: the former when we note that the Guildford Four were locked up for these bombings rather than the people who actually did it, the latter when we learn that those who actually did it were freed from jail as part of the Good Friday Agreement.

It beats me why conservatives should not care about false convictions, nor liberals about murderers being released as part of a dodgy political deal. But then, I do not see liberalism and conservatism as irreconcilable opposites, which is probably why I still have trouble predicting what the PC attitude among media folk will be, even after 20 years of working on the fringe of the media.

Elsewhere in the same issue, the reliably barking John Sutherland takes a story about a US alternative medicine quack, and manages to find it is proof, not of human wickedness and human credulousness, but of the evils of capitalism:

But the runaway success of Natural Cures also bears witness to genuinely troubling aspects of the American healthcare system. It has been estimated that some 50 million citizens have no health insurance. For these desperate people, who fall sick like everybody else, “natural cures” are all they can afford. “Socialised medicine”, as the Clintons learned the hardway, has no place in America. Capitalistic medicine does. What John le Carré calls “Big Pharma” has made America the most drugged nation in history.

Which “explanation”, unfortunately fails to account for some important facts: (1) the purportedly natural non-cures offered by quacks are not generally cheaper than the products of Big Pharma, even at US prices; (2) the most drugged nation in history, is on average (i.e., including all those without health insurance) rather healthier than Britain if you look at survival/recovery patterns for pretty much any disease; (3) The European quack industry is also fabulously successful, and expensive, despite the subsidised competition from socialised medicine.

What is particularly enjoyable about this lunacy is it appears in the same issue of the paper as a nice clear feature by the impeccably rational Dr Ben Goldacre explaining why alternative medicine offers comforts not available from a scientific physician.

It could always be worse!

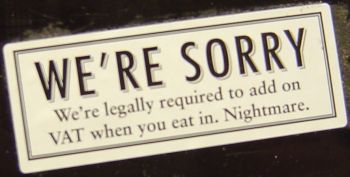

Way to go, Pret A Manger! The food is good, too.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|