We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The spooks are not stupid. There are two ways they can respond to this in a manner consistent with their current objectives. They can try to shut down the press — a distinct possibility within the UK, but still incredibly dangerous — or they can shut down the open internet, in order to stop the information leakage over that channel and, more ambitiously, to stop the public reading undesirable news.

I think they’re going for the latter option, although I doubt they can make it stick. Let me walk you through the early stages of what I think is going to happen.

In the UK it’s fairly obvious what the mechanism will be. Prime Minister David Cameron has thrown his weight behind mandatory opt-out porn filtering at an ISP level, to protect our children from a torrent of filth on the internet. (He’s turned to Chinese corporation Huawei for the tool in question.) All new domestic ISP customer accounts in the UK will be filtered by default, unless the owner opts out. There’s also the already-extant UK-wide child pornography filter operated by the Internet Watch Foundation, although its remit is limited to items that are probably illegal to possess (“probably” because that’s a determination for a court of law to make). And an existing mechanism — the Official Secrets Act — makes it an offense to possess, distribute, or publish state secrets. Traditionally newspapers were warned off certain state secrets by a process known as a Defense Advisory Notice, warning that publication would result in prosecution. It doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to foresee the creation of a law allowing for items subject to a DA-Notice to be filtered out of the internet via a national-level porn filter to protect the precious eyeballs of the citizenry from secrets that might trouble their little heads.

On the other hand, the UK may not have a First Amendment but it does have a strong tradition of press freedom, and there are signs that the government has already overreached itself. We’ll know things are really going to hell in a handbasket when The Guardian moves its editorial offices to Brazil …

– Charlie Stross

I won’t name the guy – he was talking to me in a private setting and such things should remain private – but a friend of mine came up with this rather bizarre defence of the recent fact, as unearthed by Snowden et al, that the US and other powers engage in massive, unauthorised spying on their citizens:

Governments have always done this, so why the fuss now? Accept it and pour yourself a beer.

The world is “massively overpopulated, so with all these ghastly people infesting the planet, governments need to, and will find it easier to, spy on them.

Spying on people, even in ways we find scary, is inevitable, so relax and stop getting oxidised about it.

The second of the arguments interests me because it blends the Malthusian panic about too many humans (and begging the question of what “should be done” about them), pessimism about the inevitability of spying and other outrages, and a sort of world-wearying acceptance of big government. Quite an achievement.

Of course, it maybe that the person making this argument was just trying to be a knob and wind me up (he is familiar with my libertarian views and regards them, patronisingly, as a sort of jolly enthusiasm). But his opinions are probably quite wildely held out there among people who consider themselves to be “realists” and “sophisticated”.

All suspicions which have been raised have been dispelled

– German interior minister, Hans-Peter Friedrich, referring to reassurances that British and US intelligence agencies “had observed German laws in Germany”.

It is compulsory to recite this quote in the voice of Cecil Baldwin from Welcome to Night Vale.

Dogs are not allowed in the dog park.

People are not allowed in the dog park.

All suspicions which have been raised have been dispelled.

Do not approach the dog park.

Mr Obama laments that the debate over these issues did not follow “an orderly and lawful process”, but the administration often blocked such a course. For nearly five years it appeared comfortable with the secret judicial system that catered to executive demands. It prized the power to spy on Americans, and kept information from Congress. Mr Snowden exposed all of this. His actions may not have been orderly or lawful, but they were crucial to producing the reforms announced by Mr Obama.

– The Economist

High-level whistleblowers know when they come forward that they’re sacrificing their national security clearance, likely their jobs, and quite possibly their freedom. Set aside for a moment what you think about the actions of Bradley Manning or Edward Snowden. Imagine you have a top-level security clearance, and you discover in the course of your work evidence of illegal government activity. Even going through the proper internal channels carries risks, and aren’t likely to change much, anyway. (Thomas Drake, remember, actually went through the proper internal channels to expose government spying — he was prosecuted, anyway. He now works at an Apple store.) Would you risk your career, your lifestyle, your family’s security, and possibly your freedom to expose it? How serious would it need to be for your to consider going public? It needn’t even be something as dire as national security. I’ve seen and reported on countless law enforcement officers whose careers were cut short (or worse) when they reported wrongdoing by other cops, or more systemic problems within their police agencies.

Radley Balko.

This is an issue that is unlikely to go away regardless of which political party holds sway in major Western powers. For all the talk about “freedom of information”, “transparency” and the like, the benefits of silencing awkward people are too great. And what is particularly hypocritical about all this is that governments routinely like to lecture banks, for example, on the need for their staff to sound the alarm about would-be money launderers.

Balko has interesting ideas on how to reduce the costs to those who sound the alarm.

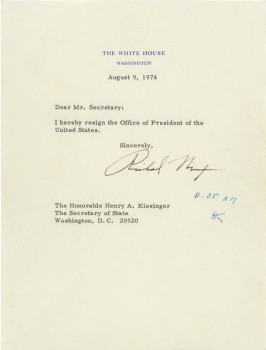

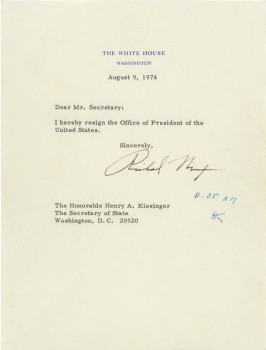

It has been less than 42 years since a US President ordered his minions to break in to the opposition party’s headquarters in an effort to conduct espionage directed at undermining them.

Now, thanks to the NSA, no one would need to physically break in to anything — a few calls would be sufficient.

People keep talking about the current NSA scandal as though privacy was something intended to keep your neighbors from finding out you listen to embarrassing music — an understandable desire but ultimately of no great importance. To believe that is why people need privacy is to completely misunderstand what is at stake here.

Richard Nixon really existed, and was really elected to office. The problem is not a hypothetical one.

Consider just for a moment what an unscrupulous President, like Richard Nixon, equipped with the information already available from the NSA could do to his political opponents, to reporters trying to find out the truth about his activities, to anyone he thought of as being “in the way”. Consider how much easier it would be for such a President to find his enemies given what the NSA has already built.

Total Surveillance Means Absolute Power.

The surveillance systems that have been developed by the NSA are too dangerous for us to permit to exist.

(39 years ago almost to the day.)

A new story from The Guardian, barely twelve hours after the last set of revelations: “NSA loophole allows warrantless search for US citizens’ emails and phone calls”.

Yes, this one is indeed far worse than the previous ones, unbelievable as that might seem.

Explaining why to those not following in detail is almost not worth it any longer, however.

A friend of mine long ago coined the term “Outrage Fatigue”, the condition in which so many awful actions by a set of State actors have been revealed that one can no longer hope to track the entire list of their offenses and crimes in one’s head.

I have long since passed that point for the Obama administration in general. Imprisonment without charge, war crimes, coverups, the silencing of whistleblowers and dozens of other acts have become so numerous that I cannot hope to remember them all.

However, I have now passed the point where, even as a putative subject matter expert, I could hope to remember even everything that has been revealed about just this one scandal.

It is painfully clear that the contempt of the Obama Administration and its minions for the rule of law is near total, that their contempt for the truth is near total, and that one’s confidence in anything they say in public whatsoever should be precisely zero.

Fears over NSA surveillance revelations endanger US cloud computing industry:

American technology businesses fear they could lose between $21.5bn and $35bn in cloud computing contracts worldwide over the next three years, as part of the fallout from the NSA revelations. Some US companies said they have already lost business, while UK rivals said that UK and European businesses are increasingly wary of trusting their data to American organisations, which might have to turn it over secretly to the National Security Agency, its government surveillance organisation.

Of course it is highly unlikely that GCHQ or its French and German counterparts are actually any less intrusive, but that said, I suspect the budget for these organisation would not keep the NSA’s staff in Cheetos and RAM upgrades, so on that basis alone I suppose your data is probably safer anywhere but the USA.

But the perception that the USA is the very worst option in the First World from a security perspective is now going to be very hard to change, whatever the truth of the matter. I did see this coming.

No one has willfully or knowingly disobeyed the law or tried to invade your civil liberties or privacies… There were no mistakes like that at all.

– General Keith Alexander

This is either delusion of omniscience and infallibility, or psychopathic contempt for truth and for the ‘little people’ who are imagined to believe whatever the great and powerful Oz says. Either way, it makes him a candidate for a straitjacket, not running an uncontrolled global para-state.

NSA Nabs Cabbie!

Yes, folks, you heard it here first! The NSA, in the midst of a full-court press to capture our hearts and minds, has revealed the secret of one of its most important cases. It managed to catch a cab driver who was sending $8,500 to Somalia. Countless lives must have been saved in the process!

With impressive results like these, it is obvious why we need a Stasi-like total surveillance state, at a cost of [redacted] billon dollars per year.

Lavabit was, until a few hours ago, a secure email hosting company with something over 400,000 customers. One of their users was (apparently) Edward Snowden.

They have shut down, apparently because they refused to assist in spying on their own clients, as similar companies such as Hushmail are reputed to do.

Unfortunately, US law now makes it a crime to discuss requests from our masters for “assistance” of this sort, so we can only assume that this is what has happened. Presuming the guess to be true, I commend them for their sense of honor. Many would not ruin themselves when faced with a choice between keeping their promises and obeying the authority of a police state.

Quoting their “goodbye” page:

“This experience has taught me one very important lesson: without congressional action or a strong judicial precedent, I would strongly recommend against anyone trusting their private data to a company with physical ties to the United States.”

If Snowden had gotten things his own way, he’d be writing earnest op-ed editorials in Hong Kong now, in English, while dining on Kung Pao Chicken. It’s some darkly modern act of crooked fate that has directed Edward Snowden to Moscow, arriving there as the NSA’s Solzhenitsyn, the up-tempo, digital version of a conscience-driven dissident defector.

But Snowden sure is a dissident defector, and boy is he ever. Americans don’t even know how to think about characters like Snowden — the American Great and the Good are blundering around on the public stage like blacked-out drunks, blithering self-contradictory rubbish. It’s all “gosh he’s such a liar” and “give us back our sinister felon,” all while trying to swat down the jets of South American presidents.

These thumb-fingered acts of totalitarian comedy are entirely familiar to anybody who has read Russian literature. The pigs in Orwell’s “Animal Farm” have more suavity than the US government is demonstrating now. Their credibility is below zero.

The Russians, by contrast, know all about dissidents like Snowden. The Russians have always had lots of Snowdens, heaps. They know that Snowden is one of these high-minded, conscience-stricken, act-on-principle characters who is a total pain in the ass.

– Bruce Sterling, who I think has his own head up his arse half the time (my god he is still clinging to the Climate Change shtick and is thus as credulous as many of the people he is inclined to mock)… but Sterling is nevertheless always a fun read because in addition to being half wrong, it is also (generally) half right.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|