We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

I hate sounding like a dried-up professor by insisting on going back to underlying concepts and definitions but in this case I will. One of the responses I received on my international ‘morality play’ was from Derk Lupinek and although he believes that we should attack Iraq and set up a democratic government, he didn’t think that we have any “responsibility” toward the Iraqi people.

It was his understanding of rights that intrigued me sufficiently to comment on it:

Rights are nothing but wishful thinking without the power to enforce them. The power of enforcement requires an emotional commitment on the part of many individuals. Each individual agrees to help enforce the rights of others and, in return, each individual gains the right to protection under the group’s power. The individual has this right because he contributes to the power that enforces the right. Individuals must contribute to the power that enforces rights or else they have no right to protection under that power. So, I think we can “call for freedom and progress for ourselves” and not feel obligated to kill ourselves helping other countries, especially when those people do not contribute to the preservation of our rights.

I detect a category fallacy in the above paragraph. The definition of a right as wishful thinking without the power to enforce it. So does it mean that where individual’s rights are abused and often cannot be enforced, they do not exist? A right is not a right unless it is enforceable and/or enforced? Just because some people do not wash, should we deny the existence of soap on the grounds of its ineffectiveness with the unwashed?

Which leads me nicely to the various concepts of rights. There are actually three versions at play here. One is the natural rights theory, which assigns inalienable rights to an individual by his/her virtue of being a human being. I will not go into assumptions behind this one here as it is a well-worn and therefore lengthy topic, suffice to say it is the one I subscribe to. That is why I cannot agree with Derk Lupinek’s subscription-based rights, whereby individual’s rights are defined arbitrarily by and within groups of individuals, and protected by a sort of social contract enforced by mutual consent.

In my post on Western intervention in totalitarian regimes, however, I haven’t used either concept of rights, natural or positivist. I was merely thinking of the individuals trapped in totalitarian regimes who never had a choice to enter in any such agreement about either definition or protection of their rights. It is that freedom of choice I feel we have some sort of moral obligation to help them obtain. Not because they contribute to the power that enforces the right or because we are somehow legally or otherwise bound to do so.

Let me put it another way. Try to explain to a child being beaten up by a bunch of thugs, that he has no right to protection since he has not contributed to the power that enforces that right. If you can manage it, you may be consistent but not very humane.

Science is a volatile subject. Traditional science originated from observations of the physical, specific and the immediate. As it progressed to modern science, the turning point being the Newtonian framework for understanding the universe, its evolution to Einstein’s theory of relativity and later quantum theory and computational science, it has increasingly concerned itself with abstract and often counter-intuitive concepts. In recent years a number of alternative scientific paradigms have sprung up and regardless of whether they end up being the next orthodoxy, they have already demolished some of the foundational theories in many scientific fields. Science, itself subject to evolution, pushes the Final Theory further as its horizons expand.

Religion is a stable and more or less fixed subject, certainly compared to science. It does make statements about physical reality and human affairs, but it does not concern itself with the temporary and the transient. I am therefore surprised that Brian can make such definite comparative statements about the two:

…the Book of Genesis makes claims about the origin of the earth and of its biological contents which, as was well understood in the late nineteenth century when these matters were first debated, are in total opposition to the theory of evolution. Either God was the maker of heaven and earth (as I was made to proclaim every Sunday morning when I recited the Creed at school) and men and beasts and plants and bugs, along the lines claimed in Genesis, or he was not.

You can’t have it both ways. Only by completely overturning what Christianity has meant for the best part of two thousand years, as the Church of England seems now to be doing by turning Christianity from a religion into a political sect, can you possibly believe that there’s no argument here.

I do not know whether you can have it both ways, but I am certainly not convinced by Brian’s argument. It doesn’t do to point out that one is ‘an orthodox twentieth century boy’ in one’s scientific ‘dogmatism’ and then proceed making sweeping suggestions as to intellectual viability of religion as a whole. The underlying assumptions at work here seem to be: a) the religious texts can only be interpreted in the 19th century fashion and b) the traditional understanding of evolution is correct and/or final. I shall not grace Brian’s use of the Church of England’s website with any assumptive force or category.

The book of Genesis, written many moons ago, does contain some very specific and visual claims about how the world came about. The interpretation Brian is familiar with would have been based on 18th century ‘deism’, a rather mechanistic understanding of the world, gradually upgraded with the scientific knowledge as it progressed into 19th century. It wasn’t until 20th century that several scientific disciplines have been shaken to their axioms but none of the tremors have yet been translated into a wider meta-contextual knowledge, quantum theory being a good case in point.

Brian says that ‘creationism’ is in total opposition to ‘evolution’. Without getting bogged down in definitions, if creationism means that the world was created, word by word, according to the book of Genesis, as some fundamentalist Christians insist, then I agree with Brian. However, that neither confirms validity of evolution as currently understood nor confines Christianity to the dustbin of the unscientific and irrational.

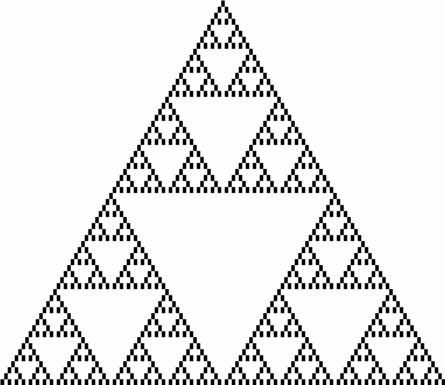

Let’s have a look at evolution. One of the foundations of the theory of evolution is natural selection. According to a modern paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, the fact that there are thousands of potential shell shapes in the world, but only a half dozen actual shell forms, is evidence of natural selection. According to my favourite scientist and complexity theorist, Stephen Wolfram, you don’t need natural selection to pare down evolution to a few robust forms. He also discovered a mathematical error in Gould’s argument and there are, in fact, only six possible shell shapes, and all of them exist in the world.

Organisms evolve outward to fill all the possible forms avaiable to them by the rules of cellular automata. [ed.note: Cellular automata are a set of self-reproducing mathematical rules.] Complexity is destiny – and Darwin becomes a footnote. A mollusk is essentially running a biological software programme.

Stephen Wolfram’s discovery about the nature of the universe suggests that the complexity that we see in the natural world can originate from very simple rule(s). One of the implications of his work is that it creates a ‘bleeding-edge’ scientific theory that proposes that the entire universe – with its perplexing combination of good and evil, order and chaos, light and dark – could have been started by a First Mover using a dozen rules.

It is therefore possible that neither science nor religion are ‘finished’ with their understanding of the nature of reality. For science, new paradigms may change the way it views the universe(s). For religion, it may not be necessary to revise its texts as the ‘creationist’ interpretation becomes irrelevant in the light of new scientific knowledge. One thing is certain though, I have more sense than to start debating religion with a devout atheist and especially one whose atheism, in his more lucid (i.e. not anti-religious) moments, is entirely rational. I merely object to the very narrow interpretation of ‘science’ and ‘religion’, namely Christianity, used to make a rather glove-in-your-face point.

Jack Heald poses some interesting questions to Brian‘s views on science and religion.

Brian Micklethwait is spot-on in his analysis of the conflict between the claims of orthodox Christianity and the claims of Darwinism. Any Christian Church and any Christian person that believes orthodox Christianity and Darwinism can peacefully co-exist is deluded.

But I wonder why someone who posts to a “critically rational” blog would claim to believe that “creationism is bunkum”.

Is it because he is already a committed materialist and Darwinism is the only theory of origins which supports his beliefs? Is it because so many so-called “creationists” are such obvious idiots? Is it because the prevailing weight of public opinion is biased towards Darwinism? Is it because anyone who claims that creationism is a better scientific model is reviled as a bible-thumping fundamentalist, and he cannot bear to be lumped in with those folks?

Surely it’s not because he has carefully weighed the evidence and decided Darwinism is a better model. I have yet to find anyone who, after carefully reviewing the data, concludes that the evidence supports the Darwinian model and contradicts the creationist model.

Are the implications of creationism a little scary? Certainly. But are scary implications any reason to avoid studying anything? Only for the uncritical and the irrational.

Jack Heald

I just took part in a French online discussion about abortion, sale of human organs, genetic material etc. It occurs to me that a libertarian point view includes the following idea:

· The components for the manufacture of human beings are legitimately tradeble.

· The finished product is not.

What is the boundary?

I cringe when Philosophers begin arguing Ethical Systems from First Principles. Codes of behavior built from argument based on mathematical rigour have a place in academia but are extremely dangerous when applied to the real world. People are not logical programs built from a rational base. They are a collection of hundreds of millions of years of gene based behavioral evolution and some thousands of years of mind based cultural evolution. Only the later of these is “perfectable”. One who thinks otherwise carries the shadow of Gulags Yet To Come in their eyes.

More so than the practitioners of many disciplines I’ve delved into, philosophers seem to place Humanity on a high pedestal of Rationality. I don’t. I see people as one more data point on a continuum of data points; a vector of traits which exist elsewhere but reach their highest expression (so far, and in our own biased eyes) in our species.

If you have decided by this point I am a follower of Richard Dawkins, then you are an astute observer and commendably well read. Dawkins changed our way of looking at evolution from one based on populations of individuals to one of populations of genes. Genes do not care about individuals (or anything else for that matter, so excuse my anthropomorphics). If a behavioral pattern kills 10% of a population but causes the other 90% to be fruitful and multiply, there will be more copies of the gene or genes (or memes if we are dealing with culture-based behavior) responsible for that behavior. Genes are the individuals which compete with each other and evolve. Not cells. Not tissues. Not wombats. Genes.

Altruism may be emphasized or de-emphasized by cultural traits and training but it can never be eliminated. It is a part of our hardwired animal program. Species with altruistic behavioral patterns will thrive at the expense of those which do not have them. It may be rather hard on an individual to throw themselves on a handgrenade or charge a machine gun nest, but by their action a larger number of the genes and memes expressed in them will survive and propagate than would otherwise have done so. It’s purely a numbers game.

I chose altruism as an example because it is currently under discussion, but the point I wish to make is a much more encompassing one. Human beings are not empty general purpose computers to be programmed at will to whatever happens to be the Perfect Ethics of the day. They come with a very large baggage of hardwired behavioral preferences which will make a mockery of the Perfectionist’s attempts to create the perfect “Your-favorite-ism” Man.

The attempt may be akin to bean-bag punching but this has never stopped Perfectionists from trying as we can see from Cambodia, Siberia, Dachau and Srbenica and Paris in the Ideological Centuries and the long line of religious pogroms stretching back into the mists of pre-history.

Last week when I posted my response to an objectivist’s objections to altruism, I knew that I was opening a can of worms. How did I know that? Because, like Brian, I am also put off by the vicious religiosity of so many Randian responses to any criticisms of their sacred texts (a few more mentions and this will be a runner-up for the most quoted phrases competition). Sacred texts may be important when it comes to discussing the underlying issues, but neither Brian nor me were doing that in our postings (see related articles below). Brian was objecting to two ‘behavioural problems’ often exhibited by the objectivists and I was responding to a general point about altruism. Therefore, Antoine, no amount of referencing to pages of the sacred texts is going to do justice to the issues raised.

I think it was perfectly legitimate for Brian to mention the fixed-sum economics in connection with the Randians. He acknowledges that they may not believe it explicitly and self-consciously any more than most other people do, but observes that ‘everything else they say is said as if they believe in fixed sum economics’. I see the fallacy sneaking in through a backdoor in their belief system – their views on altruism and its moral inferiority to selfishness.

Unearthing the ‘original’ definition of altruism that sent Rand and the objectivists spitting mad just confirms Brian’s point about ‘definition hopping’. I defined altruism as concern for other people, or unselfish or helpful actions. Randians may base theirs on Comte’s definition of altruism, which is very extreme, treating ‘devotion to other people’s interests as the ideal rule of morality’. It spells out an ethical system that goes directly against the fundamental trait of human nature – the survival instinct. (This is not to say that I do not consider ethical systems based on the conflict between our natural propensities and ethical requirements legitimate and I intend to deal with this in my sequel on Kant.) What I find unpalatable is the conclusion that altruism is immoral, disregarding a) other meanings of altruism and b) common sensical observations that selfless acts are beneficial both in themselves (make the altruist a better person) and in their consequences (the recipient of a selfless act is better off).

This brings me to my original point – perhaps Randians, in their advocacy of capitalism and the virtues of individualism and self-interest, feel that anything that undermines their ‘campaign’ must be purged. I join the campaign whole-heartedly and fervently. As Antoine points out, there still exist the sort of people who believe that profit is a dirty word, but I don’t see why, in trying to defeat them, I should leave them a monopoly on altruism, compassion and generosity.

So, Antoine and Perry, I am not denying the contribution objectivists have made to the discourse about freedom, individualism and ethics of entrepreneurship. I am merely reserving the right to disagree and object to dogmatism, inconsistency and irrational conclusions whatever direction they are coming from.

A person who derives quasi-sexual gratification from inflicting enormous pain upon helpless female victims has evil intentions, assuming we consider each human being to have certain natural rights. However, ‘natural rights’ are fiendishly difficult to derive from reason without swallowing unproven assumptions. John Locke had it simple: God made Adam, He gave Adam sovereignty over the world and all its contents. He said that Man shouldn’t kill another man. End of story. If He exists and if belief in His Judeo-Christian form were universal, we could literally announce that the sociopath pervert was evil because God said so. We could also say that property rights exist as a natural right because ‘Vox Dei’.

I regret that this sort of argument is not sustainable for all humans at this time. To announce that the depraved person is irrational, is both practically pointless (he wouldn’t care) and not based on reason at all. The only basis for condemning a criminal other than natural rights is utility – which is close to arguing for a ‘public good’. As I reject the notion of public goods, I can hardly claim that a public good justifies condemnation of someone’s gratification of their admittedly unpleasant (to me) hobby. After all if twelve monsters agree to inflict pain on one victim in secret (so the rest of the public is unaware of the act), it can’t be condemned by utilitarian principles: at some point the aggregate pleasure outweighs the aggregate pain.

It’s no good recoiling in horror at the activities of sadistic monsters (an emotional response), striking out at them, and then trying to justify the action by reason, when the rationale is unsubstantiated. I happen to think that Rand’s account of the identification of objective morality is as good as it gets from a libertarian natural rights point of view. N.B. Brian, who despises Randians, tries to derive morality from utilitarian principles. What he comes up with is decency, not rules for discovering ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Without a theory of natural rights I think libertarians are kidding themselves on the subject of ‘crime’, ‘deviancy’ and ‘justice’.

Alice Bachini enters the fray on the issue of altruism.

I don’t think that we need to define doing good things for other people for no clear personal gain as altruism. It just seems the rational way to go about things sometimes. Good things cause general improvement in all sorts of ways we can’t necessarily demonstrate or define, and knowing this is enough reason for doing them. If we don’t want to do them, then there must be a reason for that. But if we do want to, then presumably our egotistical desire is based on some sensible understanding of how things are. Preferences aren’t arbitrary things, they are based on reasoning to begin with (some of it inherited, or inexplicit, or too deep or fast for us to be consciously aware of it at the time).

On the other hand, irrational desires like the urge to murder someone or to chop off your own hands, are damaging precisely because they are irrational. So the fact that people’s preferences aren’t always necessarily good does not mean that they should not operate on the basis of egotism; it just means they should get more rational before doing things.

Basically, good things make sense and are morally beneficial, including me having a delicious burger for my lunch. Whereas bad things are irrational and morally detrimental. So I can’t see any need for altrusim at all. However, it can be very bad, if it means acting in a way that is contrary to one’s egotistical preferences, because a better thing exists. This is to reason out why we don’t feel like doing what we think we ought to do. Then we can change our preferences and do good things autonomously. Individual freedom is a good thing to seek out.

Alice Bachini

I am probably opening a can of worm or poking a hornet’s nest or something with equally disturbing consequences but I cannot let John Webb’s posting go without comment.

He correctly identified Paul Foot’s assumptions that enable him to spew out such blatant and primitive fallacies about capitalism in particular and economic reality in general. The bit I found unpalatable was his analysis of Paul Foots ‘motivation’ for such statements and his sin of ‘failure of morality’, which is supposed to be altruism. I have encountered this ‘belief’ before as it seems to be a staple argument among the libertarians of the Objectivist variety and I have always been taken aback by the ferocity of their insistence on ethical and psychological egoism and the corresponding denial of altruism. I shall take this opportunity to spell out my objections to what seem to me to be an irrational strain in libertarian thought.

John Webb states that ‘many people today mistakenly assume that altruism means having a regard for the well-being of others.’ Actually, one of the most common definitions of altruism is ‘concern for other people, or unselfish or helpful actions’. True, in evolutionary biology, it is defined as ‘behaviour by an animal that decreases its chances of survival or reproduction while increasing those of another member of the same species’. Needless to say, altruism in its biological sense does not imply any conscious benevolence on the part of the performer, imposition of which is what John Webb rallies against.

Then John Webb redefines altruism as meaning:

…”in practice, having a necessary hostility to others as a consequence of adopting something other than oneself as the very standard of evaluation. Though the precise standard of altruist morality varies depending on the prevailing ideology, the People, the Race, the Proletariat, the Gender, the God, the Prophet, the Environment, the Social Organism etc., the premise which always remains constant in the altruist’s world-view is the notion that there is some overriding standard, something other, something above and beyond and greater than the individual to which everyone should gratefully and enthusiastically sacrifice themselves.”

This is a description of collectivism (and totalitarian at that) and not altruism. The distinction is an important one, as you can have altruism without collectivism. It seems that the collapse of altruism into collectivism and vice versa for the likes of John Webb is due to a fundamental misunderstanding of what psychological egoism and self-interest mean.

If we understand psychological egoism as the theory that all human actions are motivated by self-interest, this taken as a factual claim based on observation, is obviously false: people are often motivated by emotions like anger, love, or fear, by altruism or pride, by the desire for knowledge or the hatred of injustice.

Also, it is not true that everything we can be said to ‘want’ or ‘desire’ is an enhancement or fulfillment of the self. We may want to give way to irrational rage or to wayward sexual desire, to hurt another or indeed to help another – without manifesting ‘self-love’ in any of these instances. My rage or aggression may in fact be self-destructive. The beginning of altruism is the realisation that not all good and bad are good-for-me and bad-for-me: that certain others – my close friends, say – have joys and sufferings distinct from mine, but for which I have a sympathetic concern – and for their sake, not my own. I may then acknowledge that others beyond the small circle of my friends are not fundamentally different – and so reach the belief that there are objective goods and bads as such. As one self among the others I cannot claim special privileges simply for being the individual that I am! If it is neither impossible nor irrational to act simply for the sake of another, the occurrence of satisfaction or ‘good conscience’ when we have done so is not sufficient ground for the egoist to claim that it was only for these ‘rewards’ that the acts were performed.

Nor on the other hand does the possibility of altruism mean that it is a constant moral necessity: an altruist can allow that in most circumstances I can act far more effectively on my own behalf than can any other person. A simple but crucial step separates a broken-backed ethical egoism from a minimally acceptable and consistent moral theory. It involves the recognition of others as more than instrumental to my fulfillment. I may promote my own interests and personal fulfillment, so long as I do not encroach upon the pursuit by others of their fulfillment. That is to recognize other persons as limits to my action: altruism may, of course, go beyond that in seeking positively to advance their good.

I have come across one more ‘philosophical’ misunderstanding – that of Kant’s ethics – also common among some libertarians. I will comment in a later posting.

My aim today is to point out that the often-hysterical denial of altruism is rooted in a belief rather than a rational argument. Some libertarians seem to believe that it is necessary to insist that altruism is wrong or immoral in order to provide firmer grounds for conclusions that are central and essential to their world-view. This is a world-view that espouses individualism and liberty, the belief that prosperity and freedom is best achieved by pursuit of self-interest and many other conclusions that I share. It is also a world-view that often must be expounded by what amounts to an intellectual crusade, fighting the collectivist, totalitarian and socialist dark forces. I have had the ‘privilege’ of facing those at their darkest and at the peak of their powers in a communist regime. Nevertheless, I do not think you have to deny altruism in order to defend pursuit of individual good, happiness, free market and liberty.

To be continued: In Kant’s defence

John Webb, Chairman of the the United Kingdom Objectivist Association, understand the truth about paleo-socialist Paul Foot.

“Is capitalism sick?” asks Paul Foot, Cash for Chaos, Guardian, Wednesday June 12, 2002. “Yes,” he contends, “disgustingly so. Its sickness is terminal, and it urgently needs replacing.”

As evidence for this singular claim Foot relates a litany of “misdemeanours” which have recently rocked the business community and suggests that far from being an exception to the daily practise of honest commerce they serve to illustrate what he calls “the central feature of capitalism,” namely, “the division of the human race into those who profit from human endeavour and those who don’t.”

Unfortunately for Paul Foot, all the examples he cites in support of this breathless conclusion have little or nothing to do with the free exchange of goods and services within a capitalist economy, as they are, without exception, directly attributable to governmental interference within a mixed economy.

The Enron Scandal, for example, did not occur within the context of unregulated trade or unbridled competition but within a highly charged political atmosphere so beset by graft and bogus environmentalist concerns that the caprices of an 18th century mandarin would seem enlightened by comparison.

The telecoms industry, which Foot also cites, is another unfortunate example to use as it seems to have escaped his notice that the telecom industry has the distinction of being one of the most highly regulated and licensed industries on the planet and where, in the UK, the telecom regulator OFTEL is a byword for bureaucratic incompetence.

As for the tax evasion “scandal” of Tyco – again it doesn’t seem to have occurred to Foot that such a “crime” could never have happened in a capitalist society – in a capitalist society property rights are inalienable and all coercive taxes would be prohibited by law.

Perhaps some people may be tempted to overlook Foot’s rather lame grasp of even the most elementary principles of politics and economics; after all, he must be so busy campaigning to clear the name convicted murderers like James Hanratty [whose guilt has recently been confirmed by new DNA evidence] that he probably has very little time to obtain an adequate grasp of current events.

And in any case, leaving the obvious factual errors aside doesn’t he make a valid point that the riches of the wealthy few are obtained at the price of the poverty of the many?

Well he would be making a worthwhile point if the Labour Theory of Value on which his argument rests had not been thoroughly refuted by the Austrian School of economics through Carl Menger’s theory of marginal utility more than a century ago.

No, the real problem with Paul Foot lies much deeper.

Paul Foot is not merely guilty of a failure of knowledge.

He is guilty of a failure of morality.

And the name of that failure is altruism.

Unfortunately, many people today mistakenly assume that altruism means having a regard for the well-being of others.

It doesn’t.

On the contrary, altruism, in practice, means having a necessary hostility to others as a consequence of adopting something other than oneself as the very standard of evaluation.

Though the precise standard of altruist morality varies depending on the prevailing ideology, the People, the Race, the Proletariat, the Gender, the God, the Prophet, the Environment, the Social Organism etc., the premise which always remains constant in the altruist’s world-view is the notion that there is some overriding standard, something other, something above and beyond and greater than the individual to which everyone should gratefully and enthusiastically sacrifice themselves.

According to altruism ANY desire, ANY benefit, ANY positive evaluation in this life or even the next, if Kant is to be believed, is immoral.

If you feed your child, or help an elderly stranger or the hapless victim of an unfortunate accident and feel even the slightest glimmer of vicarious pleasure yourself, then that pleasure counts as a benefit to yourself and whatever else you may have intended you have not committed a moral act.

By such a standard of morality any act whether beneficial to oneself or the whole of humanity is of no moral worth if it is motivated by the slightest concern for personal benefit.

That people might prosper by freely pursuing their own interests, to mutual benefit and by voluntary consent, without needing to inflict harm on others is an anathema to the likes of Foot.

Why?

Because Foot is a collectivist and for collectivists, all human endeavour, all profit, all property, all knowledge, all values, all human life, is collective.

Anyone pursuing their own interests for their own sake is necessarily at war with the “common good” – a “good” so rare and lofty that only “politically aware” people like the fabulous Foot can identify it.

In this view, company directors don’t earn their bonuses – they “steal” them.

One man’s “gain” is another man’s “loss.”

The rich grow “richer” and the poor, who have a higher standard of living than a medieval King, grow “poorer.”

Property isn’t created – it’s “ill-gotten.”

Wealth isn’t something to be earned – it’s something to be “shared.”

Individual prosperity above the level of “equality” isn’t desirable – it’s “excessive.”

The rich are “guilty” in virtue of their wealth.

And the living are guilty in virtue of dead murderers like James Hanratty.

So how does Foot get away it?

He relies on the reluctance of others – the very others that he would so earnestly make his victims – to abstain from making a moral judgement.

So now it is time to make a judgement.

For decades Paul Foot has sanctimoniously postured as a supporter of the underdog, a valiant champion of the outcast, defender of the weak, and a protector of the innocent.

In reality, however, his is one of their greatest enemies for all he has ever been is an altruist, his entire journalistic career amounting to nothing more than a demand for the glorification of force based on the cultivation of the vice of envy – an vice defined by Ayn Rand as “a hatred of the good for being the good.”

Is Paul Foot sick?

No.

He doesn’t have that excuse.

John Webb

Neel Krishnaswami writes:

Utilitarian arguments are the only arguments I have known to successfully convince anyone across ideological boundaries.

…and…

A political philosophy beyond utilitarianism is essential to avoid absurdity, but concrete utilitarian arguments are essential both to convince others and to keep ourselves honest.

I definitely agree with Neel in the sense that theoretical concepts ought to be supported by empirical evidence and facts. My dislike of utilitarianism is based on one of its consequences – ultimate disregard for the individual. Numerous amendments and elaborations of utilitarian ethics and political theories fail, in my eyes, to remedy this serious flaw. Neel is clearly aware of it and provides examples to this effect himself. If I understand his point correctly it is more about the workings of the human mind and its susceptibility to be convinced by ‘utilitarian arguments’ more successfully than by statements of ‘ideological bullshit’.

In my experience utilitarian arguments that focus strictly on consequences or plain facts and numbers create one of two reactions in the opposing party – either attempts to discredit the source of the information and/or desire to go forth and collect similar ‘statistics’ supporting their views.

My second reservation about utilitarian methods of a debate is that they don’t work. How else do you explain the fact that the vast regiments of lefties (apologies to Perry for using the term out of meta-context) are still polluting the media and public life with their incandescently idiotic convictions about socialism, communism and current authoritarian regimes? No statistics, facts and numbers about Stalin and other communists and the atrocities they committed on the Russian and surrounding nations managed to eliminate communism as an ideology and barely forced its metamorphosis into a ‘benign’ socialism. The facts are dismissed as inconvenient and unconvincing if they clash with fundamental beliefs. Some are happy to use utilitarian arguments to defend communism even in its original guise – I have come across people who argue that Stalin may have done some naughty things but he also turned Russia into an industrial nation. ’nuff said.

I find that the best strategy, and perhaps the most difficult, is one of exposing inconsistencies in the opponent’s ideas and hope to identify the beliefs that get in the way of a rational discourse. Beliefs are notoriously difficult to change. As one of the characters in my favourite film points out:

You can’t change people’s beliefs but you can change their ideas.

If however by utilitarian we mean anything relating to the specific, concrete and non-theoretical then we are simply using the term in different ways. Let me explain what I believe, that is, what my idea of a sound theory is and why I find utilitarianism pitifully inadequate in dealing with reality’s bigger picture. My judgement of a theory depends on three elements:

1. its content, that is its premises, logical consistency and order, its relation to reality

2. the motivation of its author and propagators

3. consequences of the theory when tested or put into practice.

To me consequences are secondary elements of a theory. They contribute to increasing or diminishing the theory’s credibility and its popularity. They can also influence the motivation of its supporters and their responsibility in upholding it. However, consequences in themselves cannot change the correctness of a theory itself; they can make neither true nor false a theory that is in itself flawed.

Neel Krishnaswami points out that we all hate it… or do we?

It’s true. Everybody hates utilitarianism. The Left hates it(1), The Right hates it(2), Libertarians hate it(3), and Adriana Cronin(4) hates it.

And we all hate it for good reason, too. It sounds so reasonable –“maximize the total happiness of society”. But it leads to such stupid conclusions. That small-town America is justified in banning Lady Chatterley’s Lover, because it offends more Baptists than turns on smut-addicted book-lovers.(5). Oops; there goes freedom of speech. That proper social policy involves enslaving 5% of the population to grow opium to keep the other 95% in a drug-induced delirium. Utility must be maximized. And finally, in a mathematical coup de grace, economists armed with the Generalized Axiom of Revealed Preference have shown that individual utility functions are not commensurable. This means we can’t even define “total happiness” in a sensible fashion, because one individual’s utility function is not on the same scale as anyone else’s.

But. (You knew that a “but” was coming, didn’t you?)

Utilitarian arguments are the only arguments I have known to successfully convince anyone across ideological boundaries. No libertarian rights-based argument I have ever constructed has ever convinced my social democrat (and outright socialist) friends of anything at all. Nor have I ever seen a libertarian react to a plea for social justice with anything other than tired sighs. But start wonking out with per-capita GDPs, life expectancies, crime rates, and accident figures, and suddenly bystanders start paying attention.

A concrete example. A couple of years ago, I was talking with a friend of mine about third world poverty. He complained that the government should do something about it. I pointed out that indeed the government did do something about poverty: mainly, it caused it. He regarded my objections to large-scale government intervention as the usual quixotic libertarianism until I offered the example of microcredit programs as an example of how to bootstrap a market and improve the lot of the poor(6). At this point my friend got really excited, because now he had a concrete charity to try and send money to.

It wasn’t a rights-based argument about why government intervention is harmful that energized him: it was a concrete, utilitarian example (and an avenue for positive action). What he cared about was people not going hungry. He also knew that in political debate, people tend to use abstractions to paper over the difficulties in their program(7). Most notorious are various leftists’ use of euphemism to justify things like the Cultural Revolution, but it’s a universal sin. He, like anyone with healthy political antibodies, narrows his eyes when vague slogans — whether “worker’s paradise”, “but it’s for the children” or even “spontaneous order” — enter the discussion. So any attempt to convince my friend had to get past his suspicion that the political jargon was just bafflegab aimed at preserving the status quo.

This is why utilitarian arguments are so useful. Focusing single-mindedly on making actual individuals better off enables one to avoid getting (correctly) killed by the “that’s ideological bullshit” reaction. A political philosophy beyond utilitarianism is essential to avoid absurdity, but concrete utilitarian arguments are essential both to convince others and to keep ourselves honest.

(1)= Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. The best attempt ever to offer a solid theoretical grounding for the social democratic program. Amartya Sen smashed it with a brief, elegant article that identified a critical algebra error in the setup. Oops.

(2)= Kass, Leon R. The Ethics of Human Cloning. Yes, this Luddite idiot is the chair of the US Bioethics Commission. It is to weep.

(3)= Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Of course you know about this.

(4)= Cronin, Adriana.“EU and e-commerce, or does Bad plus Good equal a greater Good?”, Samizdata.net March 14, 2002

(5)= Sen, Amartya. “On the Impossibility of a Paretian Liberal”. This man is depressingly smart.

(6)= see http://www.villagebanking.org/home.php3

(7)= Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language“. Yeah, he’s every conservative’s favorite socialist and every socialist’s favorite conservative, but what can you do?

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|