We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Wittgenstein’s Poker: The Story of a Ten-Minute Argument Between Two Great Philosophers

David Edmonds and John Eidinow

Ecco, 2001

“Wittgenstein’s reputation among twentieth-century thinkers is … unsurpassed. … A poll of professional philosophers in 1998 put him fifth in a list of those who had made the most important contributions to the subject, after Aristotle, Plato, Kant and Nietzsche and ahead of Hume and Descartes (p. 231).” Yet there is nothing in this book that is comprehensible to the layman about Wittgenstein’s philosophy, or even, I have to say, much of an attempt to make it so. His eminence and influence and his credibility to other philosophers we have to take on trust.

On the other hand, Popper – the antagonist to Wittgenstein’s protagonist – has two well-known and accepted achievements to his credit, his book The Open Society and Its Enemies and his “falsifiability” theory on the structure of scientific hypotheses (though I have often wondered if “vulnerability” would not be a better term). But in Britain and America, Popper is slowly being dropped from University syllabuses; his name is fading, if not yet forgotten … a penalty of success rather than the price of failure (p. 230).” Or perhaps, being transferred from the useless category of philosopher to that of scientist? Far from turning his office there into a shrine, the LSE has had it converted into a lavatory.

The allusion in the title is, of course, to the famous incident with the poker on Friday, 25th October, 1946 about which none of the supposedly acute seekers after truth present could agree. This was the only time the two philosophers actually met, though both came from Vienna, both were of Jewish descent (though neither of religion), and both had to leave Austria when the Nazis took over. As far as I can make out, the dispute was whether philosophy, as a discipline, could or should deal with real “problems” (Popper) or merely with “puzzles” (Wittgenstein), say with language expressions. The meeting was of a discussion group at Cambridge University, called the Moral Science Club (MSC), of which Wittgenstein was actually the Chairman. He was, however, usually overbearing and difficult, tending to hog the discussions, often leaving meetings half-way through – something Popper probably didn’t know.

Popper had been invited to give a paper and Wittgenstein interrupted and shouted his disagreement, making his point brandishing the poker that lay by the moribund fire, laying it down when Russell told him to, and then leaving. Smoothing matters down, someone asked Popper for an example of a moral principle. “Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers,” was the reply, provoking a laugh and, I imagine, relaxing the tension. Popper later claimed that Wittgenstein was still present when he made this retort, but the general agreement is that he had gone, one witness even accusing Popper of lying. The poker itself disappeared.

The book, however, is much more than an account or investigation of this episode. Tracing the lives of both personalities, both of them combative and obsessive, the authors also fill in the background they grew up in – the increasingly anti-semitic Vienna of the post-WWI war decades, despite the efforts of those of Jewish ancestry to assimilate, including many who discarded their religion and became Christians. Wittgenstein’s was an extremely rich family (though his grandfather had adopted the name of his aristocratic employer, to whom he was not related) but he divested himself of his own share of its wealth. He had served with distinction in the Austrian Army in WWI, volunteering for dangerous posts, being decorated several times and during it writing his seminal work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. He ended the war in an Italian POW camp. On the other hand Popper, some thirteen years younger, came from a bourgeois but impoverished family. He had difficulty in escaping from Austria; with perhaps some exaggeration he claimed that taking a Chair in New Zealand left free for another (Waismann) an opening to a temporary lectureship at Cambridge (p. 221). His “war effort”, he said, was writing The Open Society (p. 71), though he tried, unsuccessfuly, to join the armed forces as well. “Popper’s impact on academic life [in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand] was greater than that of any other person, before or since,” judged that institution; he acted as a kind of intellectual champagne after the dry depression years (p. 172).”

Wittgenstein died in 1951, Popper in 1994. The authors do not try to give much information on the later work of either, though there is a joint chronology (pp. 245-242). They do seem, in my view, to be somewhat biased against Popper, if only because he’s left more evidence against himself; presumably also they cannot help but be influenced by the poll of philosophers given above (and in which, presumably Popper comes nowhere). Neither men come across as particularly pleasant, let alone lovable, though Popper seems to have kept friends as well as making enemies, while the impression is given that Wittgenstein despised everyone – no list of friends is given for him, though mention is made of disciples and acolytes who imitated his mannerisms. Although Popper died only six or seven years before the book was written and published, there is no indication that either author ever interviewed or even met him. It is also a little disappointing that no mention is made of any relationship between him and other thinkers on the right, such as Bauer and Hayek, who, in contrast with both Popper and Wittgenstein, was noted for his courtesy towards opponents. Perhaps these don’t qualify as philosophers. Isaiah Berlin is mentioned, but once only to have his philosophical pretentions pulverised by Wittgenstein (p. 24), and twice in passing.

A minor but irritating typographical blemish is the close resemblance between 3 and 5.

An interesting post by A.E.Brain, an Aussie blogger, on contrasts between style and substance when it comes to governments:

The most reviled form of Government in recent times has been National Socialism. With Good Reason. The two most famous – or infamous – National Socialist parties have been the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – National Socialist German Workers’ Party) AKA “Nazi” party, and the ANSP (Arab National Socialist Party) AKA “Ba’ath” Party.

But… a bad form of Government executed by Good People is better than a good form of Government executed by Bad People. therefore present for you a contrast in styles, of two “National Socialist” movements, though one of them didn’t call itself that. Judge for yourself.

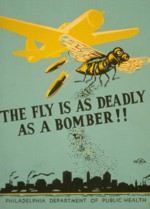

National Socialism often conveys Public Service messages in

militaristic terms, but not always

I do agree with A.E.Brain that there are similarities in the ways that states, regardless of their ideology, usurp a prominent place in the social interactions. It is the desire for total politicisation of the civil society that makes Communism and Nazism such intimate ideological bed-fellows. Practically too, there is not much difference between a concentration camp and a gulag, except the fact that many more millions died in gulags. As a commenter in this thread put it:

The commie shoots ’em in the head,

The facist, in the skull.

Their ideological differences

For victims, rather null.

The US posters skillfully juxtaposed with their Nazi ‘counterparts’ use identical imagery and the similarities in style are meant to be sinister. But it should not really come as a surprise, since propaganda toolbox was not as ‘diverse’ in those days and both Nazis and Communists would have used and perfected the ‘marketing’ techniques of the day. The more subtle reminder is the pervasive hijacking by the state of the ‘positive’ collective sentiments that are transformed into a collectivist norm imposed by force.

A.E.Brain concludes:

What’s important is the matters of Substance, like the very real differences that existed between the Franklin&Eleanor team and Adolf.

Absolutely. There is only one small fallacy in his argument. Propaganda does not equal style, at least not in any meaningful sense. So although National Recovery Administration (NRA) was no doubt bureaucratic and authoritarian in its nature, I cannot see the implementation of its policies being even vaguely reminescent of the ways of Nazi or Communist institutions. In the end, precisely because of its authoritarian substance (and style), the NRA did not last long enough to even fully implement its policies.

What the posters demonstrate is that States have instinctive tendencies to take over the society whether by force or ideology or a threat of external/internal enemy. Toxic ideologies will turn the state into an instrument of terror. Credible or fabricated external/internal threats will enable the state to expand its powers and effective use of force will make the state a frightening tool in the hands of those who wield it.

The difference is not just what those who are in power believe but also what kind of society they face. Both Communism and Nazism have taken over the societies where the rights of individual were not paramount. It is when individual is no longer valued as the corner-stone of the society and his freedoms protected from collectivist impositions, the state is unrestrained in its natural course.

Over at the Adam Smith Institute’s Weblog, Madsen Pirie says:

There is another view which says that politics matters less these days. When the UK government provided houses and jobs for many of us, and ran the electricity, gas, oil and phone companies, together with steel, coal, ships and cars, it mattered who was in charge. With less coming from government and more from ourselves and the private sector, it is not as important. People tend to vote heavily in high tax countries such as Denmark, and less so in low tax countries such as the USA.

In other words, if politics (i.e. the scramble for the favour of the majority) becomes less important, voting goes down.

Many libertarians, notably Perry de Havilland of this blog, believe that the same idea in reverse is true – that by not voting we can reduce the politicisation of our lives. ‘Let them wither away to irrelevance,’ he says. I’m not so sure. It might be one of those nasty paradoxes such as the one whereby safety breeds lack of vigilance, which makes us less safe.

Perhaps the first to stop voting are those who have achieved relative independence, leaving disproportionate influence to those still at the trough. Have any studies been done on this? And does anyone know what percentage of those eligible to vote in, say, 1900 when the State was very weak, actually did so?

That’s the view put forward by Madsen Pirie in this blog posting and an accompanying essay. Madsen also says that the Conservative Party might not be all that conservative at the moment. Of Hayek, he writes:

It is necessary to draw this distinction between the conservative disposition as a personality trait and the political tradition which bears the same name, because while Hayek eschews the former he can be accommodated within the latter. Hayek’s own desire to move towards a freer society fits in well with the conservative preference for a society whose outcome is the product of actions by its members, rather than that of rules imposed by leaders.

Interesting take – do read it with Hayek’s own essay on the subject.

I am glad to see that the august publishing house, the Oxford University Press, has recently published a monster-length encyclopaedia of the Enlightenment. For those who can stump up more than three hundred pounds, this would be a most impressive addition to any library. From David Hume to Diderot, the book is a treasure trove of facts and articles about the folk who helped shape our world and mostly for the better.

Let’s hope university libraries stock this book as essential item since it is bound to be beyond the financial means of most undergraduates. And perhaps the OEP could make a gesture of sending a few copies to the nascent academies I trust will be springing up in post-Saddam Iraq.

Here in the US, we have recently been diverted by the spectacle of a state Supreme Court judge defying the orders of a federal court in order to violate the Constitution. The state judge refused to move a gigantic copy of the Ten Commandments from the courthouse, where its prominent placement and enormous size at least arguably amounted to “the [state] establishment of religion” in violation of the US Constitution. Now, this is just the sort of topic that seems to exert an irresistible compulsion on people to wander off into the tall grass of irrelevance, so I will leave aside the legalistic arguments about whether the placement of the Ten Commandments actually violated the First Amendment to the US Consitution as applied to the states via the doctrine of incorporation (and I beg the commenters to do likewise).

While there are subcultures in the US that could undoubtedly recite all ten, I daresay most US citizens could not, although they are widely held in a kind of iconic way to represent the root of law and morality. Indeed, the claim that they are an historical source of US law was made in the campaign to keep them in the courthouse. Christopher Hitchens takes a look at what the Commandments actually say, and concludes that they don’t have much to do with morality or modern law at all.

The first four of the commandments have little to do with either law or morality, and the first three suggest a terrific insecurity on the part of the person supposedly issuing them. I am the lord thy god and thou shalt have no other … no graven images … no taking of my name in vain: surely these could have been compressed into a more general injunction to show respect. The ensuing order to set aside a holy day is scarcely a moral or ethical one . . . .

There has never yet been any society, Confucian or Buddhist or Islamic, where the legal codes did not frown upon murder and theft. These offenses were certainly crimes in the Pharaonic Egypt from which the children of Israel had, if the story is to be believed, just escaped. So the middle-ranking commandments, of which the chief one has long been confusingly rendered “thou shalt not kill,” leave us none the wiser as to whether the almighty considers warfare to be murder, or taxation and confiscation to be theft.

In much the same way, few if any courts in any recorded society have approved the idea of perjury, so the idea that witnesses should tell the truth can scarcely have required a divine spark in order to take root. To how many of its original audience, I mean to say, can this have come with the force of revelation? Then it’s a swift wrap-up with a condemnation of adultery (from which humans actually can refrain) and a prohibition upon covetousness (from which they cannot). To insist that people not annex their neighbor’s cattle or wife “or anything that is his” might be reasonable, even if it does place the wife in the same category as the cattle, and presumably to that extent diminishes the offense of adultery. But to demand “don’t even think about it” is absurd and totalitarian . . . .

It just goes to show that it never hurts to periodically reexamine first principles. With a little luck, I can probably get through the week without violating more than six (and no, it is none of your business which six).

Some of Samizdata’s more socially conservative readers seem to think gay marriage is a bad idea. But trying to work out why they hold that view is, at least at first, puzzling. They rail against social freedom saying that it leads to social degradation and also to lots of government spending. Well, I’m against ‘social degradation’ and ‘government spending’. So why don’t I agree with them?

The reality is that homosexual marriage would not lead to any degradation whatsoever. Homosexuals already live in a society where on the whole they are able to be open about their sexuality, and are able to have sex without the government arresting them. If the government lets two gay people marry, that if anything encourages fidelity. If you ask social conservatives to explain how this causes social degradation, the response is… BLANK.

The idea that homosexual marriage means that government spending has to go up is just plainly stupid. Homosexuals don’t have children, so they don’t impose the cost of education on the taxpayer. They generally die younger (although I suspect this will change), meaning they impose less cost in terms of pensions. If they split up, the taxpayer doesn’t have to look after the mother because both partners generally work.

The social conservative arguments are quite obviously bogus.

Could the real reason why social conservatives oppose gay marriage be much simpler? They oppose it because they hate gay people. They think it’s disgusting what these faggots do. They think the state should punish them for their depravity.

If not, could they perhaps explain themselves?

Peter Cuthbertson doesn’t like social liberalism. In a comment on The Liberty Log, he attacks free-marketeers who also favour social liberty:

So they advocate a smaller state while they also want government to promote behaviour that forces immense financial burdens onto the state? Greaaat.

I respect Cuthbertson a lot, and he writes an excellent blog, so I’m going to take the time to point out why I think he should reconsider his view.

Those who favour social freedom are not asking government to promote any behaviour at all. They are asking government to be neutral – to let people make their own choices. As for saying that it “forces immense financial burdens on the state”, this is exactly the same argument used in the early 1980s by the Left. Every time the government came up with a policy that would involve nationalised industries employing fewer people, this form argument would be brought up. Miners, they argued, were producing something and formed part of cohesive communities. Destroying the mining industry would force financial burdens on the state, destroy the family, violate rights…

Cuthbertson falls into the trap of believing that when the government doesn’t regulate people’s social affairs, society will deteriorate. Yet I suspect that many of the institutions he values – like marriage – have been in decline despite being controlled by the government. The problem of single motherhood has been an entirely government created phenomenon – not because of it being legal (it always has been) but because of government welfare.

Measures to reduce government involvement in social affairs should be welcomed. Labour’s proposal on gay unions does not encourage straight people to be gay. I think Cuthbertson would agree with me on that. But the policy will have a profoundly beneficial effect on gay culture, encouraging gay people to enter into more stable, longer-lasting relationships. Here we have a case of social freedom encouraging the sort of society that, I guess, Cuthbertson would like.

The reality is that over time society changes its attitudes. It is no longer socially acceptable to attack homosexuality. To do so is taboo. But despite developments in how people view the world, the government is often not very good at developing social institutions to cater for these progressions. In crude terms, it is often the inability of government to react to market forces that leads to social degeneration, not the market forces themselves.

Even on the drugs issue, where many people argue that legalisation or decriminalisation would lead to social degeneration, one should not ignore that degeneration is what we already have. 75% of crime is said to be drug-related, caused by the black-market price. Drugs being illegal doesn’t stop people using them.

No one wants a degenerate society. The difference in opinion is between those that think government control is that best way of society flourishing, and those who think that devolving the evolution of society to individuals and civil society works better. I, for one, go with the latter.

There really are some clots out there, nearly all of them collectivists, of one kind or another. You give them a debating point, they complain about the debating hall. You give them a nice hall, they complain about the expense of the hall. Whatever the point is, they avoid talking about this central issue, and stick to some peripheral soft target. They perhaps even convince themselves, after enough posts of gibberish, that they’ve won the debate, rather than had us laugh at them, in the very best style of Jeremy Paxman interviewing some New Labour ministerial half-wit. And then, when we do sometimes manage to press them to actually talk about the matter in hand, they start shouting, and screaming, as soon as they realise their childish threatening game is up.

But aside from these fun and games, what they’ve failed to realise, is that the reason most of us classical liberals are classical liberals, no matter what our starting position was — whether socialist, fascist, communist, Last Tory Boy, or whatever — is because we have been prepared to argue our case in a sensible calm fashion. This argumentative debate is often an internal one, too, arguing with ourselves, as well as an external one, arguing with others. → Continue reading: The unbearable lightness of clots

A leaked memo revealed that David Blunkett is pushing the Cabinet to back national identity cards for everyone aged 16 and over, carrying biometric information, such as fingerprints, to allow police to confirm the holder’s identity. Under Mr Blunkett’s scheme, the card will cost £39 for most people between the ages of 17 and 75.

An opinion piece about the identity cards news in Telegraph is yet again explaining what is wrong with Blunkett’s argument. Basically, each of the claims made by the Home Secretary in support of his pet scheme is wrong.

- First, Mr Blunkett says that there is strong public support for the idea. In fact, the Home Office’s recent consultation exercise focused on the concept of an entitlement card, a very different prospect. (Also, according to this Out-law article, the goverment has admited that the public opposes the ID card scheme.)

- The Home Secretary goes on to argue ID cards will help fight crime. This is one of those assertions that is forever being made, but hardly ever substantiated… The public mood is said to have changed since September 11, 2001, but no one has explained – or even seriously tried to explain – how ID cards would have thwarted those bombers, many of whom died in possession of forged papers.

- Nor, by the way, are ID cards a solution to illegal immigration. The root of the asylum problem is not that we cannot find clandestine entrants, but that we never enforce their deportation.

- More faulty still is Mr Blunkett’s central proposition, as set out in a letter to his Cabinet colleagues: “The argument that identity cards will inhibit our freedom is wrong. We are strengthened in our liberty if our identity is protected from theft; if we are able to access the services we are entitled to; and if our community is better protected from terrorists.” In an appendix to Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell describes how a concept can be traduced if the words used to express it lose their meaning. The example he gives, uncannily, is the word “free”. Now here is Mr Blunkett using “freedom” to mean more state control.

- Any doubts as to the wisdom of the scheme must surely be removed by the Home Secretary’s final argument in its favour: that we are “out of kilter with Europe”. Indeed we are, thank heaven. Policemen in Britain are seen as citizens in uniform, not agents of the government.

The most worrying is Blunkett’s spin on the concept of freedom. In his view we are strengthened in our liberty if our identity is protected from theft; if we are able to access the services we are entitled to; and if our community is better protected from terrorists. This is vaguely based on the distinction between negative and positive liberty, which are not merely two distinct kinds of liberty; they can be seen as rival, incompatible interpretations of a single political ideal.

Negative liberty is the absence of obstacles, barriers or constraints. One has negative liberty to the extent that actions are available to one in this negative sense. Positive liberty is the possibility of acting – or the fact of acting – in such a way as to take control of one’s life and realize one’s fundamental purposes. While negative liberty is usually attributed to individual agents, positive liberty is sometimes attributed to collectivities, or to individuals considered primarily as members of given collectivities.

Blunkett and his New Labour chums are classic and rather unexceptional anti-liberals. (I use the term liberal in its original meaning, based on negative definition of liberty and claiming that in order to protect individual liberty one should place strong limitations on the activities of the state.) In Blunkett’s mind, the pursuit of liberty (whether of the individual or of the collectivity) requires state intervention, which, by definition, is not contradictory with limitations on personal freedom. As a result, the protests of civil liberties groups do not make sense to him.

The concept of freedom as being unprevented from doing whatever one might desire to do is alien to him. According to Isaiah Berlin the defender of positive freedom will take an additional step that consists in conceiving of the self as wider than the individual and as represented by an organic social whole – “a tribe, a race, a church, a state, the great society of the living and the dead and the yet unborn”. The true interests of the individual are to be identified with the interests of this whole, and individuals can and should be coerced into fulfilling these interests, for they would not resist coercion if they were as rational and wise as their coercers.

I will not grant Blunkett’s social and political philosophy such level of ‘sophistication’. I will say that his are the simple and toxic insticts of a collectivist and a statist and that those protesting policies based on them will have their words muffled by the Big Blunkett.

Cross-posted from White Rose

Arthur Silber, whose “Light of Reason” blog I generally admire, is not very happy so it seems with our own Perry de Havilland for his recent dig at Jim Henley over the outcome of the recent Iraq war. Now, I am not going to revisit this increasingly well-flogged dead horse.

No, what I want to consider is a more general issue of principle. Arthur is a follower, in broad terms, of the ethical egoist philosophy set out by the late Ayn Rand. Rand denounced all those philosophers who enjoined Man to sacrifice his happiness and values for some other, usually mystical or collective, “good”. Instead, she set out an alternative, the “virtue of selfishness”, questioning why it is wrong for man to acquire and keep a value, including non-material ones such as respect, and freedom.

Arthur’s basic disagreement, so it appears, with those like Perry and I who have advocated toppling Saddam seems to rest on the idea that is is “altruistic” and hence wrong, to wish to liberate countries such as Iraq. No truly “selfish” libertarian could possibly endorse such regrettably altruistic behaviour, particularly if it costs blood and treasure. Force is only ever justified, on this view, if one has been directly attacked already and has the names, addresses and confessions of the attacker.

I think Arthur misses a key point. Consider the following – suppose that it is clear (and it is) that the bulk of Iraqi people hate Saddam and want rid of him (the Baathist thugs who benefitted from his rule are naturally not so keen). Suppose that the Coalition’s armed forces regard it is a great value to them that they should serve in forces which enable them to liberate folks from tyranny. This would be even clearer if they were funded like mercenary armies by consenting adults rather than through coercive taxation. Well, if these sort of considerations apply, the liberation of Iraq is a deeply “selfish” act on the terms that Rand would have seen it. It is a positive sum-game for both the liberators and the liberated.

Now of course none of the above resolves the more immediate issues of whether Bush and co exaggerated the WMD threat, whether Iraq was the most pressing issue after 9/11, or whether Saddam was clearly in direct cahoots with terror groups. My point is more fundamental. Many isolationists seem to have elevated the non-initiation of force principle to the level where it inadvertently seems to endorse the existence of particular nation states, including those run by the most brutal folk imaginable. What is so libertarian about this? Why should an Iraq, Soviet Union or a Nazi Germany’s national borders be accorded the same respect as those of a liberal democracy?

By all means let us preserve good manners in the libertarian parish. But those who argue that intervention a la Iraq is always and everywhere wrong are not, in my humble opinion, entitled to claim that those who differ are not libertarians.

And by the way, 99 percent of the stuff on Arthur’s blog is just brilliant.

In case our esteemed readership has not yet heard of FLAIR (the Far-Left Alliance of Indignant Revisionists) I have the pleasure to relay an interview taken from its case files.

The interview was conducted by Barry Fest, a long-time associate and one-time student of Brummagem Groat, who agreed to interview his erstwhile mentor on behalf of FLAIR. The occasion was the publication of Dr. Groat’s latest book, I Dunno: The Working Person’s Guide to Postmodern Relativism by the Belverton University Press. Dr. Groat is professor emeritus of Talkmatics at Belverton.

An Interview with the Relativist

FLAIR: Thank you for your time today, Dr. Groat. I’d like first to ask you about the subtitle of your new book, “The Working Person’s Guide to Postmodern Relativism.” Why does the working person need a guide such as this?

GROAT: For too long the working person has played victim foot soldier for the corporate conglomerates and their Pentagon enablers. Whenever the corpagon has wanted to go to war to protect profits, it has used absolutes – most notoriously the absolutes of “right” and “wrong” – to persuade the working persons of one nation to take up arms against the working persons of another. And whenever working persons have seemed ready to establish a government for working persons, the interested powers have eliminated the threat by appealing to the absolutes embedded, like post-hypnotic suggestions, in the subconscious of the working person. The rote inculcation of these absolutes is performed at an early age by traditional family units, which act as manufacturing plants for the corpagon’s future pawns and patsys.

The result is that by the time the working person is old enough to actually start working, he is a thrall of these absolutes and does not even know it.

I Dunno is intended to persuade the working person that he is better off without absolutes. – What we in the West consider right and wrong is not what everyone else in the world considers right and wrong. I try to make it plain that, in fact, one man’s wrong is another man’s right. Until working persons learn to accept this they will continue in their roles as ad hoc button men for their corporate bosses.

FLAIR: At what point did you realize there was a need to convince Joe – if you’ll pardon the colloquialism – Sixpack of the need to trade in his old absolutes for new ones?

GROAT: I’ve always – Wait a minute, I think you may be missing a very important point. It isn’t that this so-called Joe Sixpack needs newer or what you might even call better absolutes. He needs to discard the notion of absolutes entirely.

FLAIR: And what is the most compelling reason for him to do that?

GROAT: As I said, it will be impossible for him to find that his notions of right and wrong will be accepted by everyone. A notion of virtue produced by the Western process of reason will not be accepted in those societies that reject reason. – And how can you have a universal truth that is not endorsed universally? The Westerner, and that includes the working person, needs to take another approach: the approach I describe in I Dunno.

For the full text of the interview visit The Radical Capitalist.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|