We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

If I emerge from the front door of my block of flats, but then realise that I have forgotten to bring my camera with me, then, unless I am in an extreme hurry, I turn around, go back up the five flights of stairs to my home, and get my camera. I cannot bear to be out and about in London without it, being a ever-more voracious photographer of whatever I see on my perambulations that interests me, and that’s more and more, the more I think of different interesting things to keep track of.

Plus, I just know that if I am not careful in this way, then the one day when I do not have my camera with me will be the exact day that an Airbus 380 on its way into Heathrow gets into trouble so serious that it is visible even to me, and plummets down into central London.

One of the things I like to photograph is the front pages of newspapers, because of their often amusing or arresting headlines. I mostly do this in the shop where I often buy my monthly copies of the Gramophone and the BBC Music Magazine (by “music” this magazine means classical music) and my weekly copies of the Radio Times, so the proprietor doesn’t mind me photographing other things. He knows that I am not going to buy any of these newspapers, but that I might be about to buy something else, and that I regularly do, even if maybe not on that particular day.

And, I take a lot of other photographs, of such things as cranes, bridges, Big Things, roof clutter, signs and notices, and other digital photographers, especially when they are engaged in photographing such things themselves, or in photographing themselves.

All of which is my explanation of why I took the photo below (on March 14th 2014) but then forgot about it, until I went trawling through my photo-archives seeking something else entirely:

I couldn’t find that exact story on the www, but here is the Evening Standard version of the same thing.

For me, this is always an interesting moment in the see-saw that is now British politics, between regimes which contrive as much government as the voters feel they can afford and regimes which unleash more government than the voters feel they can afford. (The option of having less government than the voters feel they can afford, is not, alas, considered worth offering.)

I cannot remember to the nearest year when the Blair/Brown regime was reported as having pushed public sector pay above this same mark, contriving a country in which public sector workers were, on average, reported to be getting more than private sector workers, but I do remember noticing that moment, and thinking it of some significance.

And this latest little tilt in the balance between production and predation strikes me as significant also, and worth noting here even if the announcement happened a couple of months ago. Just for now, for the time being (or so it says in the newspapers): production gets you better wages than predation. Good.

I know, I know. As good news comes, this is pretty small stuff. After all, even this feeble milestone took them four years to get past. As “austerity” goes, it is very mild indeed. But it is good news, I think. And I particularly enjoy being told it by a newspaper which so obviously disapproves of the story that it is telling.

Nicholas Dykes, someone I have known for many years, and who is the author of several excellent novels – as well as essays such as this pugnacious and scholarly piece about Karl Popper – emailed me the other day to make it clear that his absence from the airwaves did not mean that he was no more.

Over to you, Nick:

Sorry I haven’t been in touch. I had something called a subarachnoid haemorrhage, a rarish kind of stroke, at 6.30 am on Sunday 24 November, falling on the floor in front of my wife and making horrible noises in my throat. Happily she’s good in a crisis and with the help of a kindly neighbour had me in an ambulance pdq. I was taken first to Hereford, then to a new Hospital in Birmingham, the Queen Elizabeth, where I was operated on next day. The NHS has its moments.

I had 2 operations. Then I got pneumonia. Then I got an infection of the brain called ventriculitis. Some cheery medic said at one point I’m lucky still to be here. I was in and out of Intensive Care, five weeks in hospital altogether, then had to go back in again with a mini stroke called a TIA just a few days after being let out.

Anyhow, I’m home again now and recovering slowly. I was weak as a kitten to begin with, slept a lot, and had great difficulty with my balance — very wobbly walking. Things are better now but my short-term memory is not too good. Happily, my speech is alright and I have not been left with any physical disabilities other than weakness, which should improve. I do have a handsome scar on my forehead however, it looks as though someone hit me with a axe.

My poor wife Rachel had a miserable time for weeks, not knowing how I’d be from day to day and with tubes sprouting all over my body. As for me, I was largely unconscious and remember very little! When I first woke up and was told what had happened, all I said was: ‘what a bugger!’

The best of recoveries to you, Nick.

Have you ever heard or read a speech in real life or fiction that left you inspired, moved, exalted, perhaps even blinking back tears… only to remember a minute later that you fundamentally disagreed with every word?

There is a theory that suggests to be good at business you must be hard nosed, ruthless, dishonest and fight for everything. It essentially suggests that business is a form of warfare carried out by individuals against each other where the winner takes all. It states that if you’re not tough enough you shouldn’t get involved in ‘business’.

This I have learnt is complete bollocks. Yes, there are bastards out there – lots of them. But the essence of good business is cooperation and honesty. It’s about finding and working with decent and honourable people. Men and women who value what you do, pay you on time, go that extra mile for you and want to achieve the same things as you.

You can, if you desire, swim with the sharks. You may even become the biggest shark. But most of the time you will end up swimming round in circles wasting time, money, resources and energy on people who simply don’t deserve that time. And certainly aren’t paying you a fair rate for it. These people will stop you achieving your goals and add no value to your life or your business.

My advice is simple. Be the good guy or gal, fight clean and keep away from the time wasters, charlatans and arseholes.

– Rob Waller

Be warned that this is not one of those “now read the whole thing” postings. That is the whole thing, apart from the title (“On Swimming with Sharks”) and the words “end of sermon” at the very end. And now you have those words here also.

If Michael Jennings can roam the world taking photos, then I can roam London and nearby spots, doing the same. Here are twelve photos from my year, one for each month.

They are chosen, I hasten to add, as much to help me say things about what is in them and about digital photography as for their technical quality. Which is… rather variable.

→ Continue reading: My year in twelve pictures

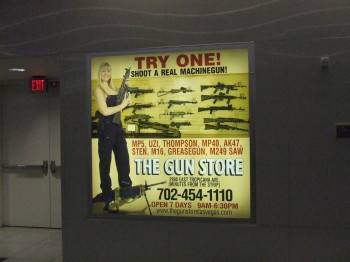

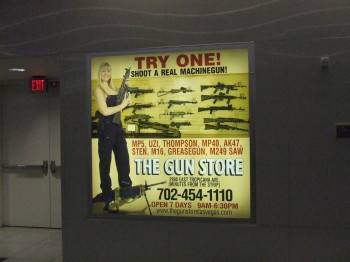

A couple weeks ago I had a several hour stop over in Las Vegas on the way from Chicago to LA. Las Vegas has never been one of my favorite places since I do all my gambling in real life and find little need for games of chance. However, this one sign may be enough to draw me back for a visit…

A very good reason to visit Las Vegas. (Copyright Dale Amon, All Rights Reserved)

Jonathan Abbott, whom we have seen mentioned on Samizdata before, has a rumination on not so much on environmentalism’s excesses but the underpinning psychology.

There is a type of person that needs to be part of a Big Cause. They cannot seem to accept the probability that they live in unexceptional times, that they themselves are thoroughly ordinary and will leave no lasting mark behind when they are gone. The number of individuals that substantially affect the course of history is vanishingly small and the mass of real progress takes place in tiny steps carried out by anonymous individuals. It is usually only in the collective total of our uncoordinated efforts that mankind as a whole advances in any way.

Some Big Causes do greatly benefit mankind (such as the programme to eradicate smallpox) but most, however well-intentioned initially, result in great harm. Many of the most damaging ones, for example fascism and communism, require another Big Cause to end them. Adherents to a particular Cause will necessarily not see it as just another campaign for progress, but as THE Big Cause, the movement that will change the historical paradigm and catapult humanity into a dazzling future.

Carrying out the personal actions prescribed by The Cause marks them out as one of the elect, and from then on no matter how commonplace other aspects of their life may be, they will have made their mark. They mattered.

This sort of belief is terribly seductive. As noted above, I do not think that all Big Causes are harmful, and I am not suggesting that only a bunch of no-hope losers would sign up for a Big Cause. However, for the most popular Big Causes of the twentieth century, this sort of optimistic, wishful thinking turned out to be a mere fairy tale. Indeed, the brutal and violent nature of the Big Causes of the previous century meant that only a sentiment-based, appeal to emotion Cause such as Climate Alarmism could arise in their wake.

And now as the end-game of Climate Alarmism as a major political force comes into view, I find myself wondering what will be the effect on the mass of its adherents. Historical Big-Causers such as Robespierre, Mao and the majority of their followers went to their graves convinced they had been doing the right thing, never renouncing the horrific by-products of their dogmas. Once signed up to a Big Cause, few ever leave. Will it be the same for the Alarmists?

One of the things that I find hardest to swallow is that the political, NGO and civil service fools wasting vast quantities of public money in the name of Alarmism are told on a daily basis by their fellow travellers in the media that they are doing a Great Thing. They are resolutely building a better world for everyone, especially for the oft-invoked archetypal grandchildren. Most of these apparatchiks will go to their graves convinced they spent their lives helping their fellow humans.

Even if the science behind their beliefs becomes publicly as discredited as that which denigrated plate tectonics, they will excuse themselves as being the innocent and well-meaning victims of deception. Their ignorance is their shield.

For the hard core of true believers, the Alarmist Cause will never die and they will follow it resolutely into the sunset, becoming the Trotskyites and Eugenicists of the future. Irrelevance will swallow them. For the less resolute, who come to accept the fall of Alarmism (or at least realise it has become a waste of time), the banner of other Causes will be raised instead. The beginnings of these new Causes will even now be growing and are probably already visible, just not gathering much media attention. Yet.

My guess is that many of the Alarmists will deflect their anti-capitalist neo-ludditism into campaigns against genetic engineering and nanotechnology; nascent movements to oppose both are already growing. Inevitably they will once again claim unequivocally that the science is on their side, even as they shut down scientific debate and rail against genuine scientific progress.

Unfortunately, it will not be until long after the worst Alarmists are dead that they will finally be grouped with the Malthusians and Lysenkoists as they deserve.

John Stephenson argues for the need to ask religious moderates about the motivations behind their actions. Are moderates – seeing faith as virtuous – tacitly defending fundamentalists (who are the genuinely committed believers), allowing them to become the “tail that wags the dog”? Moreover are religious moderates actually engaged in religion because they are “humanists in disguise”?

One of the problems with engaging religious folk in conversation is the fact that, before falling victim to the charge of being “angry” or “strident”, we find that the rules of discourse and logic are warped and violated beyond recognition. Find me a religious fanatic who doesn’t endorse his faith through the actions supposedly committed in its name and you will have probably found me a liar.

It may not seem apparent during regular conversation – phrases such as “well as a practising Catholic” or “Judaism preaches kindness” are regularly greeted with admiration or at the worst, ambivalence – but it is when we strip away someone’s faith that such statements are shown to be contemptible. Are we really to believe that, without the promise of eternal life, the religious among us would resort to hedonistic violence and acts of self-indulgent debauchery? Suppose that next week the Abrahamic religions were shown to be apocryphal. Would we suddenly hear reports of Justin Welby snorting cocaine while out partying with Desmond Tutu and a gang of strippers? Of course not.

As is the case, kindness in the name of God or religion is done with a knife to your back. Good deeds done for fear of punishment or in receipt of reward are hardly commendable, yet believers still wish to play a numbers game – stressing the good work done in the name of Christ or Allah or some other Bronze Age almighty. Admittedly from my own experience some of the nicest people I know are devoted Christians yet, unlike the many who act as though this gives some form of credibility to the story of Adam and Eve, I pay them the honour of assuming they would behave in such a way if they did not have religion to fall back on.

Secularists such as Daniel Dennett and Richard Dawkins are keen to avoid a war of words with the religious over who “does more” – the understanding being that they are first and foremost passionate about the truth and not the resulting human behaviour of unproven tales. But perhaps more ground can be made by appealing to altruism before detailing the logical arguments against a given theology.

The fact that what we perceive as a sense of morality is innate within humanity as opposed to religion is evident by virtue of the cherry-picking so commonplace among moderate believers. Among casual Church of England Christians for example, the Sermon on the Mount may be advocated yet the more abhorrent elements of Deuteronomy or Leviticus will be ignored. I suspect that a large proportion of these individuals are religious in name alone and that, for the most part, their attendance comes as a result of habit or an intrinsically vague idea that to attend church constitutes as a “good thing”. These people have often given very little thought to the doctrine their religion entails, but understand church to be a place of warmth and community – things that most of us are drawn to.

→ Continue reading: Moderates, good deeds and religious fanaticism

The idea that we are living in a period that in retrospect we might call “The Crazy Years” gets an airing in this long, essay by John C. Wright. He takes the term from Robert A Heinlein’s “Future History” series of stories, written decades ago when the Grand Master of Science Fiction was not yet fully famous. (Thanks to Charles N Steele’s excellent blog for the pointer).

Steele, in his own ruminations on this, says:

Robert A. Heinlein explored a possible future history for homo sapiens. One of things he foresaw was a period at the end of the 20th Century and beginning of the 21st that he called “the Crazy Years,” in which cultural fragmentation and decay in advanced countries generates political and economic decline and social disruption. He was prescient in recognizing what happens when commonly accepted principles such as an individual’s responsibility for self are forgotten and political correctness and multiculturalism run amok. As advancing technology places increasing power in human hands, human ethics fail to keep pace. In Heinlein’s world, humans do manage to navigate these shoals without destroying themselves and eventually do settle on a MYOB sort of libertarian ethic…but only narrowly averting nuclear self-destruction and environmental self-destruction, and not without going through periods of dictatorship as well as societal chaos.

Steele then lays out a number of areas where signs of our descent into the Crazy Years might be evident:

-

Iranian or Al Qaeda religious fanatics obtaining nuclear weapons…

-

An American federal government — especially the executive branch — working to acquire unlimited power, and already apparently having the power to spy on essentially all communications, everywhere…

-

A growing segment of the population — some poor and some very rich (think Goldman Sachs) — who live as parasites on the productivity of others while creating nothing of values themselves…

-

An intelligentsia that cannot bring itself to condemn Islamism for fear of being seen as insensitive or racist or ethnocentric, but which regularly denounces, in the most hateful terms, anyone who opposes the continued expansion of state power…

-

An intelligentsia that praises socialism, hunter-gatherer economies, massive interventionism, anything but the one system that actually works, free market capitalism, a system they bitterly condemn…

-

A “press,” our mainstream media, that sees its job as promoting political positions and readily lies when lies serve this goal better than truth, and spouts nonsense the remainder of the time, apparently because reasoned analysis is too hard.

He then goes on to argue – and I hope he is right – that reasons for pessimism are perhaps overdone. For instance, who would have predicted that, after 1945, the continent of Europe (albeit apart from the Balkans in the early 90s) was free of any serious armed conflict of the sort that has routinely ravaged the region for centuries, and that the Cold War came to an end without the Soviets or NATO firing hardly a shot at one another on the continent?

I would add that in the confines of the UK, signs of craziness are evident, for example, from the political classes. Take the recent UK Labour Party conference. Labour leader Ed Milliband wants to impose a freeze on the prices that electricity companies charge their customers, while simultaneously demanding that they invest more in things such as renewable energy; his reversion to the idea of draconian price controls is pure demagoguery. Remember, dear Samizdata readers, that the Millibands of this world are quite popular with large chunks of the electorate. Labour is leading – just – the other main party – the Tories – in the opinion polls. This is what happens when, in such a crazy period as ours, that people are encouraged to think blatantly contradictory things: electricity firms must charge less but do more and invest more; banks must hold more capital in reserve but lend more; we must intervene in foreign lands but only with “surgical strikes” and nothing else; that everyone must be given access to health insurance but that the cost mustn’t rise; that we must ban opinions and notions because someone might be offended, and so on and so on.

Of course, thinking nonsense such as this is hardly new. Big business, for example, has been demonised as long as big business has existed, and political targeting of this has been almost the norm, rather than the exception. But what makes me want to think of this issue within the broader “crazy years” context is that I doubt that Milliband and his fellow socialists would be so confident of pushing these notions were it not for the rather batty political climate in which we now operate. Part of the cause for this may be a temporary reaction to the credit crunch, and the false narrative that quickly took root. But then the willingness of people to believe this narrative (which leaves out the role of central banks and government and blames it on “bankers”) is itself a sign that something is very wrong and cannot be quickly put right.

Robert Heinlein’s “future history” stories certainly do pay a re-visit. Come to that, so do pretty much all of his writings right now.

(Addendum: in case anyone brings this up, Steele could have mentioned any of the big banks as “parasites” in his list of examples. He chose Goldman Sachs, but he’s not picking on it specifically.)

I stumbled across this rumination of 97-year old architect Jacque Fresco, about how to make a better world.

And it apparently involves living in symmetrical planned cities with identical modular architecture, no doubt presided over by wise technocrats like Jacque Fresco, who presumably decide who gets issued with what in a cashless future in which a drone class of otherwise superfluous people are free to go to school and write plays apparently.

His better future looks a lot like my vision of hell.

When I was a boy of about sixteen or so, I had a conversation with my godmother, a Canadian lady of great warmth and generosity. She was a Christian and she asked me, having not met me face to face for a year or two, whether I was also. I said: No. She said: Why not? I said: Because it isn’t true. There is no God, Jesus was not his son, there was no virgin birth, and so on. Her answer to my atheistical declarations stuck in my mind, because it seemed then to be and seems still to have been such a very odd one. She said that I might want to consider being a Christian on the grounds that Christianity was, potentially, very comforting. In adversity, it is nice to believe that there is a God who is looking out for you and who is on your side.

The oddness of this comfortingness argument for Christianity is that it suggests that you can decide what you believe, or to put it another way, that you can be comforted by deciding to believe something that you did not believe until that moment. But belief – surely – doesn’t work like that. It doesn’t mean that. What you believe is what you believe. If you do not know what you believe but are curious (perhaps because someone else has asked you), then you face a task of discovery, not a decision. You need to study the claims being made about the alleged truth in question by others. If you already know about these claims, to the point where you are able to identify what you believe about them, then you need to look inside your own head to see what is there. But you don’t decide what is in your head. And you certainly do not decide what you “believe” to be true merely by thinking about what you would be comforted by if you thought it was true, but which you have no other reason to think is true. Truth is one thing. What would be comforting if true is something entirely different.

On a closely related matter, it would be very comforting if the world always rewarded virtue, but most, me included, agree that it does not. So, say some Christians, Christians not unlike that godmother of mine, wouldn’t it be nice to believe that if the world does not reward virtue, God does? Well, it might be, if you really do believe this. But, I don’t, and my reasons for not believing that God rewards virtue are likewise nothing to do with how nice it might be if he did. What a very bleak world you live in, say the Christians. Maybe, say I, but you live in it also. You just don’t realise it.

My central point here does not concern the truth or falsehood of my atheist beliefs, or of Christian beliefs. I believe what I believe and you all believe what you all believe, and no amount of commenting here or anywhere is going to change any of that. Rather, I am making a point about the nature of belief, and it is surely a point that many Christians would agree with me about, because they too often speak of their beliefs having been discovered by them rather than merely decided. I didn’t decide that Jesus is my savour, they say. I realised that he is, and he is. (When people really do believe something, they often omit the bit where they might say “I believe”, because they are dealing with truth itself, their own belief in the truth being a somewhat secondary issue.) I didn’t choose my atheism as if choosing a bag of sweets in a shop, and Christians mostly don’t choose Christianity in that kind of way either.

It would seem, however, that some people at least really can and really do decide what they believe. (I recall a conversation with a religious believer who described having chosen his religion in exactly this sort of way, as if choosing a house.) Others believe what they believe about such things as politics in a similarly decisive way. They really do seem to possess the power of wishful belief, as it were. They really can decide what they believe. To me, this is very odd.

The above – somewhat strange – ruminations began life as an attempted start to a rather different Samizdata piece to this one, about the kinds of things I believe that got me writing for Samizdata in the first place, and about some of the other things I also believe, all of which things I also believe because I believe them, rather than because the truth of them is any great source of comfort to me.

After the My Lai massacre, only one person, William Calley, was charged, and then only after enormous public outcry. He ultimately served 3.5 years in house arrest for ordering and participating in the murder of at least 347 and possibly as many as 504 Vietnamese civilians, presuming he had no knowledge of the gang rapes and mutilations of bodies, which seems unlikely given eyewitness accounts.

The events of My Lai were initially covered up, itself a crime, but no one was ever charged for participating in the coverup.

During the massacre, Hugh Thompson, Jr. saved countless lives by ordering his helicopter crew to protect innocent civilians from execution. For his trouble, he was initially given a medal for a non-existent event in an attempt to shut him up, then condemned in public once the true events were revealed. The Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Congressman Mendel Rivers, went so far as to say that Thompson was the only person in the incident worthy of punishment.

Has the world changed much?

Today, it was announced that Bradley Manning, whose chief de facto offense was providing the US public with evidence of multiple war crimes, will be serving ten times the length of William Calley’s punishment, 35 years, and in a real prison rather than house arrest. The people who committed the war crimes he revealed evidence of will never be charged.

(On the latter, if you have any doubts that he revealed criminal activity, compare, as just one example, the video of the helicopter machine gunning of two Reuters reporters in Baghdad with the official DoD investigation report of the incident, which had full access to said video. Even if one can bring oneself to believe that the incident itself was not a crime (although it almost certainly was), the subsequent investigation was a fabricated tissue of lies. The events in the video and those described in the investigation report are manifestly not the same. Presumably those engaging in this coverup believed they could never be caught because the video was improperly classified to aid in the coverup, itself a crime. The coverup itself was a felony — but no one was charged but the messenger.)

The State protects its own. It cannot be trusted to police itself.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|