We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The Reconquest of Spain

D. W. Lomax

Longman, first published 1978

It is surprising to read (p. 179), “There seems to be no serious book in any language devoted to the history of the whole Reconquest,” (at least when the book was published in 1978) despite the fact that it would seem to be the underlying theme of the history of the Middle Ages in the Peninsula, with the nice firm dates of 711-1492. The author commends O’Callaghan’s A History of Medieval Spain.

Like everywhere else, from Persia to the Atlantic, Islam rolled unstoppably over the whole of Spain, except its tiny northern edge, probably leaving that out in favour of richer pickings in southern France. Even here, in Asturias, only active resistance to the Arabs ensured the survival of the tiny state and an early civil war amongst the Moslems led to the withdrawal of disaffected Berbers from northern territory which was then occupied by Christians.

The author claims, with some evidence, that quite early the ideal of Reconquest was the ambition of the Christian kings and people. However, the initial Ummayad emirate, subsequently caliphate, flourished until the end of, and particularly during, the tenth century, though the last caliphs were puppets. It is probably this period of the Muslim occupation that has been idealised as a time of toleration by Muslims of Christians and Jews, though these were definitely second-class citizens and persecution of them not unknown.

The break-up of the caliphate enabled the Christians to advance again, with some assistance from France; also the crusading ideal, though mainly focussed on Jerusalem, was some help, sometimes by crusaders en passant. The capitulation of Toledo, even though it remained something of an outpost, signalled this. However, about 1085, some of the Muslims, in desperation invited in from North Africa the Almoravids, a puritanical sect (often hated by the more liberal decadent Spanish Muslims) who, in the great battle of Sagrajas (1086) halted the reconquest. The Cid (1043-99) is of this period. Much of the time he as often served Muslim kings as Christian, but after capturing Valencia, “was the only Christian leader to defeat the Almoravids in battle in the eleventh century”. (p. 74)

By this time the Christian states were Portugal, Leon-Castille (gradually united), Aragon and Navarre, sometimes allied, but more often not and generally with no scruples about fighting each other with Muslim allies. However, Aragon was pushing down the Ebro valley, taking Saragossa in 1118, though the Almoravids fought back successfully to prevent it reaching Valencia, which had been evacuated after the death of the Cid.

Like the Caliphate before them, the Almoravids disintegrated and were largely replaced, from 1157, by another sect from Africa, the Almohads, who soundly defeated the Castilians at Alarcos in 1195. This defeat seems to have first cowed then roused the Christians (particularly the Pope); finally Christians from all the Spanish kingdoms, and some from France, united in a campaign which won the decisive victory of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212). In the forty years after the battle the Almohad empire broke into pieces which were annexed by” Castile and Aragon. Vital cities – such as Cordova (1236) and Seville (1248) – passed permanently into Christian hands so that “by 1252 the whole of the Peninsula was nominally under Christian suzerainty” (p. 129), though this, of course, did not mean the end of Muslim kingdoms.

The pace of reconquest slowed down, initially as a result of another transfusion from Africa, the Marinids, who, however, could only defend the Muslim rump. In 1340, at Tarifa, their sultan was decisively defeated and no successor state in Africa invaded Spain again. Muslim Spain survived as Granada for another 150 years, the Christians occupying much of the time fighting and rebelling against each other. One is forced to add: when they should have been completing the Conquest. The process, when it happened, certainly united Spain. In the end, “Fernando and Isabel could cure one crisis in 1481 simply by setting the war-machine to work once more to conquer Granada.” (p. 178)

The author, at his Conclusion makes the persuasive claim that “Only Spain [and also, I suppose to a lesser extent Portugal, which he does not mention] was able to conquer, administer, Christianize and europeanize the populous areas of the New World precisely because during the previous seven centuries her society had been constructed for the purpose of conquering, administering, Christianizing and europeanizing the inhabitants of al-Andalus.” (p. 178) As so often in books published from the 1970s on, the maps leave much to be desired; certainly places are mentioned in the text which are not to be found on them.

Two days after I had finished this book I listened to a discussion on “Cordovan Spain” under Melvyn Bragg’s chairmanship on Radio 4. The three other participants were Tim Winter, a Muslim convert, of the Faculty of Divinity, Cambridge University, Mary Nickman, a Jewess (carefully correcting herself from AD to Common Era) and an executive director of the Maimonides Foundation, and Martin Palmer, whose voice was not to me sufficiently distinguishable from the first, an Anglican lay preacher and theologian, and author of A Sacred History of Britain. Although the consensus was largely positive about the Ummayad regime, and their tone “multicultural” in the modern sense, the first two did seem to agree that the three religions, while coexisting, did not indulge in dialogue, let alone interpenetrate. This confirms an episode mentioned in the book, that even when promised immunity in a bilateral debate, a Christian was executed “when he expressed his real opinion of Mohammed”. (p. 23) Nor was the Koran translated into Latin “until the twelfth or thirteenth century”, someone said in the discussion. Needless to say, the rosy view of Muslim Spain did not take into account that the Muslim conquest fatally disrupted Mediterranean civilization, the burden of Pirenne’s Mohammed and Charlemagne. To pick up the shards and pass a few of them on does not strike me as a very large recompense.

The Age of Reagan: I 1964 –1980

Steven F. Hayward

Prima Lifestyles, 2001

This is a very long book (718 pages + another 100 pages of notes etc.) and it is somewhat daunting to realise that in due course a second volume will come to complete the story. It might be as well to say that this is emphatically not a biography, not even a political biography; the title and the sub-title The Fall of the Old Liberal Order make this clear. It is more a history of the times, from the anti-Goldwater landslide of 1964 to the Reagan landslide of 1980. The cumulative impression of the book itself is its richness and how its detail ministers to its analysis.

And it is a sorry, not to say a frightening tale, telling as it does of the collapse of American self-confidence and the rise of the counter-culture of self-hatred amongst its elite. The narrative is admittedly partisan, but at the very least a case that needs to be put. As for the Presidents of the period, Hayward’s judgements are that Johnson was irresolute, reacting to events minimally, Nixon misguided, obsessive and unfortunate, Ford a mere stopgap and Carter simply disastrous. All of them seemed to have underestimated Soviet malevolence and overestimated Soviet stability; for the latter the intelligence services seem to have been especially at fault.

For anyone who has been misled into thinking that Reagan was an intellectual nullity, here is ample evidence that he was an independent and original thinker, often insisting on keeping to his own line or script in face of criticism from his advisers and speechwriters. Many of his statements, which at the time seemed naive, questionable, wrongheaded or too extreme now seem merely farsighted. He was also optimistic about America and had no time for any rationale for its decline, such as Kissinger, student of the rise and fall of European states, believed in, or at least feared. Nor was he put off by the “complexity” arguments of those who despised him for his simple attitude to problems and their solutions. Some of his difficulties with his own advisers and supporters lay in persuading them that this attitude could be made plausible to the public as electorate.

As much as the first two thirds of the book, however, has little mention of Reagan, for it is a history of how the US got into the messes that Reagan, it is fair to say, rescued it from. By far the biggest mess, which he was too late to do anything about, was, of course, the Vietnam War and it is quite plain that the left-leaning media and intellectuals, combined with political ineffectiveness and downright ignorance, contributed overwhelmingly to its being lost. To illustrate US political masochism: the two “war pictures” that had the greatest negative impact on home support – execution of the Vietcong prisoner and the napalmed little girl – won Pulitzer Prizes for the photographers.

It is not exactly necessary to be reminded, but it is necessary to bear in mind that it was under two Democrat Presidents, Kennedy and Johnson, that the US entered and enmeshed itself in the Vietnam “quagmire” (though this is not a term I recall being used by the author). The muddled, incremental escalation of the conflict by Johnson is described in Ch 4. It was also a Democrat Congress, not the President, the hapless Ford, that abandoned the South Vietnamese, even refusing to supply them arms.

Even more so was Cambodia betrayed, and the dignified reproaches of their leaders, as they refused the offer of evacuation by the American ambassador, to face certain death, make sad reading (p. 408). It is a terrible comment on what the consensus was that Reagan’s characterisation of the US effort in Vietnam as a “noble cause” was regarded as eccentric and chauvinist, just as later was “evil empire” (but for the latter’s vindication see The Week, 15/2/02, p. 13).

All through the account is woven the political manoeverings of various, almost forgotten presidential hopefuls and their minions. The ups and downs of Reagan’s two bids for the Republican nomination and the campaign that won him the Presidency, are given in great detail. On the other hand, his two terms as Governor of California are more lightly sketched in (or are perhaps less memorable). A fine book, which should be better known.

On BBC 2 last night there was a programme in the series ‘Seven Wonders of the Industrial World’.

This particular episode was on the building of the Transcontinental Railroad in the United States.

As one would expect the show did not present the companies involved (the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific) in a very positive light. And the BBC have a point – the companies were subsidy grubbing, brutal and corrupt.

However, it was also clear from the programme that the the Central Pacific was less brutal, less corrupt and more effective than the Union Pacific.

Some things the programme did not mention (for example the Central Pacific’s policy of ‘buying off’ Indians – rather than just getting the army to kill them). But it did show that although the Central Pacific Railroad were ruthless they were not the killers (of Indians and Whites) that the Union Pacific were. The programme also showed that the owners of the Central Pacific actually cared about their company (rather than just considering an object to be looted as Durant of the Union Pacific did).

Furthermore it was clear that the Central Pacific overcame vast physical obstructions to the building of a railroad and that its people (White and Chinese) showed creative thought and vast physical effort in overcoming these obstructions.

In the end the Central Pacific won the race to get to the rendezvous point decreed by Congress – and had to wait for two days for the Union Pacific to turn up.

Fantasy presents conflicts as being between good guys and bad guys. However, in real life conflicts are more often between bad guys and worse guys (although later in American railroad history J.J. Hill does appear to have been a genuine good guy).

It was good for the soul of America that the bad guys (rather than the worse guys) won the race.

There’s an article in today’s New York Times, an article about another article, in Homes & Gardens. But follow that Homes & Gardens link and you won’t find any mention of this article, because it was published in 1938 and was about Adolf Hitler’s “Bavarian retreat”.

The predominant color scheme of Hitler’s “bright, airy chalet” was “a light jade green.” Chairs and tables of braided cane graced the sun parlor, and the Führer, “a droll raconteur,” decorated his entrance hall with “cactus plants in majolica pots.”

Such are the precious and chilling observations in an irony-free 1938 article in Homes & Gardens, a British magazine, on Hitler’s mountain retreat in the Bavarian Alps. A bit of arcana, to be sure, but one that has dropped squarely into the current debate over the Internet and intellectual property. This file, too, is being shared.

The resurrection of the article can be traced to Simon Waldman, the director of digital publishing at Guardian Newspapers in Britain, who says he was given a vintage issue of the magazine by his father-in-law. Noticing the Hitler spread, which doted on the compound’s high-mountain beauty (“the fairest view in all Europe”) at a time when the Nazis had already gobbled up Austria, Mr. Waldman scanned the three pages and posted them on his personal Web site last May. They sat largely unnoticed until about three weeks ago, when Mr. Waldman made them more prominent on his site and sent an e-mail message to the current editor of Homes & Gardens, Isobel McKenzie-Price, pointing up the article as a historical curiosity.

Ms. McKenzie-Price, citing copyright rules, politely requested that he remove the pages. Mr. Waldman did so, but not before other Web users had turned the pages into communal property, like so many songs and photographs and movies and words that have been illegally traded for more than a decade in the Internet’s back alleys.

Still, there was a question of whether the magazine’s position was a stance against property theft or a bit of red-faced persnicketiness.

Now this episode could be turned into yet another intellectual property comment fest, and if that’s what people want, fine, go ahead. But what interests me is the ineptness of the commercial Homes & Gardens response, their woeful neglect of a major business opportunity. An honest response from them about their reluctance to get involved in political judgements of the many and varied political people whose houses they have featured in their pages over the decades, and about all the other famous (and infamous) people whose homes they’ve written about over the years, together with a website pointing us all to their archives, might surely have served their commercial purposes far better, I would have thought.

This might have morphed into a discussion of the comparably fabulous pads occupied by other famous monster-criminal-dictators (including some featured in Homes & Gardens, of the exact degree of opulence/disgustingness of the homes of the Russian and Chinese Communist apparatchiks, but of their far greater reluctance (when compared to openly inegalitarian despots like Hitler) to reveal their living arrangements to the world, in the pages of such publications as Homes & Gardens. There might also have been some quite admiring further thoughts on the nice way that Hitler had arranged matters for himself, from the domestic point of view, the way the design of the house made maximum use of the view of the mountains, etc., etc. It does sound like a really nice place.

Such a discussion could surely have been combined with a robust defence by Homes & Gardens of their intellectual property rights under existing law, and in a way that might have been to their further commercial advantage. They might have simply reprinted the entire piece in a current issue, together with their current comments about it.

But no. Down go the shutters. And an opportunity to bring Homes & Gardens to the non-contemptuous attention of a whole new generation of readers, instead of to its contemptuous attention, is missed. Or is about to be missed. → Continue reading: Hitler’s home in Homes & Gardens

I have been reading a remarkable book about a remarkable period in British history – the mid- to late 18th century – when a group of entrepreneurs, gifted amateur scientists and political radicals helped create the foundations of much of our modern industrial world.

The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow, looks at the lives of a small but amazingly influential group of men, particularly the ceramics genius Josiah Wedgewood, pamphleteer and scientist Joseph Priestley, engineer Matthew Boulton, steam engine king James Watt, and medical doctor Erasmus Darwin. What jumps off the page is these men’s tremendous sense of drive and enthusiasm for acquiring and sharing knowledge. They were great polymaths, seeing no division between the pursuit of abstract knowledge and practical concerns of money making.

Most of these men were consciously outsiders, eccentrics and radicals ill at ease with the Anglican establishment. That sense of being ‘on the outside’ I think partly explains their drive to succeed. Most of them notably were unable for religious reasons to attend the main English universities of Cambridge and Oxford, often attending Scottish academies instead or bypassing such places altogether. And I was also struck by the sense of limitless possibility afforded by a country which at the time imposed very few restrictions and taxes on the public. 18th Century Britain was a bit like the Silicon Valley of the 1990s, with powdered wigs. Of course there were restrictive practises such as merchant gilds and duties on some imports, but that period surely came about as close to a genuine model of laissez faire capitalism as we have ever seen in our history.

There was much that was very bad and ugly about that period in our history, but also a great deal worth preserving and emulating today. The entrepreneurial gusto of these men is something we could surely use today. Glorious geeks indeed.

It would be quite wrong to suggest that the issue of self-defence (and the law relating thereto) is a libertarian issue. But it is probably true that, for many years, there was next to no debate about it as an issue outside of libertarian circles.

For free market advocates, self-defence (and the natural right thereto) is not just an important issue, it is a cornerstone of individualist philosophy. Yet, while libertarian scholars and writers debated passionately about the issue, it barely registered a blip on the radar of wider public interest.

That is, until a certain Tony Martin shot two intruders who had broken into his remote Norfolk farmhouse, killing one of them. The news that he had been arrested and charged with murder, led to a broken-dam deluge of furious and passionate debate about the right of self-defence and which flooded every medium.

Overnight, it seemed, self-defence had become a hot topic, not least because, as with so many debates, it has tended to generate more heat than light.

I do not intend to simply re-hash the Martin case and the various reasons why his actions either were or were not justified. That has already been done in some length here and elsewhere. What I want is to examine the reasons why practical self-defence has, to all intents and purposes, become illegal in the UK.

The obvious starting point is the law itself. While I believe that broader phenomena have played their part in creating the current situation, it is critical to examine how they worked to shape both law and custom as it stands. → Continue reading: The way we were

A couple of weeks ago, while taking a little tour of Provence, I found myself in Arles, once a great Mediterranean port but today a small town with some spectacular Roman ruins, famous for being the location where Vincent Van Gogh painted many of his most famous works, as well as being the place where he cut off his left ear.

In one of the town squares, I found a fairly ordinary and old looking memorial to the events of the second world war.

However, there was a very new plaque on it. Let’s get a closer look.

This is quite intriguing. Unless the servicemen in question did something extremely famous, it is unusual to find a memorial to one or two specific men. (At least, it is outside graveyards). While the sacrifice of every soldier or airman who died is worthy of commemoration and remembrance, the numbers who died were so great that it is not possible. So why these two? Were Lieutenants Tippett and McConnell the only Americans to die in Arles in the war? If not, what did they do to merit this memorial? And why was this plaque not erected until almost 60 years after the action in question? Were more details as to what happened in the war only found out recently? Had some historian who knew what they did long campaigned for such commemoration. One senses that there is an interesting story there, either about the actions of the men themselves, or at least about how the plaque came to be erected. I googled for their names on the internet but found nothing. I am sure that if I wrote to the mayor of Arles to ask, I would receive a letter back telling me the answer. However right now I don’t know anything. Still, if any readers of this site know anything, I would be interested to hear it.

And it is worth noting that the citizens of at least one French town felt the need to erect another memorial to the American sacrifices made in 1944 in liberating France as recently as last year. Not everyone forgets.

How exactly did the Cold War end, and who exactly won it, and lost it?

I like this summary, provided by someone or something called “The Friendly Ghost”, which he (it) wrote in response to the accusation that the current President of the US has also been telling the occasional untruth.

When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, he was briefed on the military capabilities of the U.S. and the Soviet Union. At the end of the briefing, Reagan asked, “Is that all the forces we can afford?” The answer was yes. The president then asked, “Then how can the Soviet Union afford such a huge military?” He was told they couldn’t. At that point, Reagan decided to see the Soviet Union’s 20-year military build-up, and raised them Star Wars.

Now, President Reagan couldn’t just say he was building a shield to shoot down ICBMs. He had to demonstrate that the technology actually worked. But it didn’t really work. So the decision was made to rig the tests, so that it looked like the system worked. In other words, HE LIED. But the Soviets believed the lie, and bankrupted themselves trying to catch up to the Americans. Gorbachev eventually came to power, and shouted “glasnost!” A few years later, the Soviet Union dissolved.

The moral of the story? By telling a lie, Ronald Reagan helped bring down the United States’ biggest, most powerful enemy, without firing a shot. Sun Tsu would be proud.

I’m not exactly sure what the provenance of the above is. It seems to be a summary of things that the Friendly Ghost guy got from this guy.

The Friendly Ghost then continues, in his own voice, so to speak.

Yes, the story is a simplification of events. But a couple of months ago, I watched a documentary on the History Channel about Star Wars. The Soviets really were that paranoid about SDI, at least for a few years. Although by the time of the Reykjavik Summit, there was some suspicion about the effectiveness of SDI, Reagan’s actions in not giving it up helped sustain the illusion in many minds in the Soviet leadership. But the most telling statistic? When the Soviet Union fell, it was discovered that the CIA had woefully underestimated Soviet military spending. The Soviets were spending 25% of their GNP on their military. Yes Virginia, there was a reason the Soviet Union fell. The military spending killed the economy. And why were the Soviets spending so much on their military? Two words: Ronald Reagan.

I was always of and remain of the opinion that the proper percentage figure for Soviet “defence” spending was one hundred.

A lot of my libertarian friends, acquaintances and competitors believe that the USSR would have collapsed anyway, a victim of its own “internal contradictions” – i.e. its useless economy, inability to make PCs or washing machines or jeans or decent cars, or make sensible use of fax machines and photocopiers.

My feeling about that is, maybe it would, but how might it have collapsed? Had the old USSR not been faced by a weapon-wielding USA breathing fire, brimstone and Tom Cruise movies all over it, and flashing cool photos of stealth bombers all over the place, might the USSR not have collapsed outwards, so to speak? Might it perhaps have attacked lazy, fat, pre-occupied Western Europe, in order to get more plunder, and to divert its domestic population from its domestic griefs with foreign glories, Henry V style – and because it preferred going out with a bang to going out with the whimper that it actually did go out with?

My favourite end-of-Cold-War moment came in the late eighties when, on a British TV show, a Dimbleby asked Caspar Weinberger what defence spending was being “prioritised”. Said Weinberger, after a thoughtful pause: “Well, pretty much everything.” I knew then that it was over.

I know, I’m a libertarian and I’m not supposed to enjoy stuff like that, but I did and I do. Given what Reagan could do with the buttons he had on his desk, and did not have, I think he did very well.

I have been enjoying the television documentary of the American war of Independence shown over on the BBC (yes, that pinko channel!), presented by military historian Richard Holmes.

Bestriding around the countryside, Holmes is excellent. He even looks the part with his bearing and military moustache – you could imagine him in an army officer’s uniform circa 1940.

During his trip Holmes asked some locals on a bus travelling near Charleston about what the war meant to them. One elderly lady gave an articulate take, arguing about the issues of taxation, representation and liberty. And then he spoke to a young guy, probably in his early 20s, who came out with this gem. I paraphrase slightly:

Well, it was all about rich folks, who just did not want to pay their taxes. If it hadn’t been for them, we’d be British, and enjoy (!) socialised medicine.

So there you have it. Some of the younger American generation wish that George Washington had lost so that all Americans could use the National Health Service.

Don’t know whether to laugh or cry, really.

The dominant ‘story’ of economic development is that science gives birth to technology, and technology makes money. But who pays for science? That has to be the government, the community, all of us. Because, who else will? So, economic development depends on a strong state, because only a strong state will pay for all that science.

Terence Kealey, in his book The Economic Laws of Scientific Research, tells a different story. Strong states destroy freedom. Weak states allow it, and thus allow capitalism, which pays for technology, which stimulates, pays for and is in its turn stimulated by science (the causal link between technology and science is that technology causes science at least as much as science causes technology), and technology also (Kealey accepts the usual causal link about this bit) causes increased prosperity.

The early chapters of this book supply an excellent potted history of pre-industrial Western Civilisation and its development. Here are the paragraphs that describe the fall of the Roman Empire:

So unconcerned with research did the Roman State become, that the Emperors actually suppressed technology. Petronius described how: ‘a flexible glass was invented, but the workshop of the inventor was completely destroyed by the Emperor Tiberius for fear that copper, silver and gold would lose value’. Suetonius described how: ‘An engineer devised a new machine which could haul large pillars at little expense. However the Emperor Vespasian rejected the invention and asked “who will take care of my poor?”.’ So uncommercial had the Romans become, their rulers rejected increases in productivity. In such a world, advances in science were never going to be translated into technology. Thus we can see that the government funding of ancient science was, in both economic and technological terms, a complete waste of money because the economy lacked the mechanism to exploit it.

The fall of the Roman Empire was frightful. The growth of the Empire had always been based on conquest, and the Empire’s economy had been fuelled by the exploitation of new colonies. When the Empire ran out of putative victims, its economy ceased to make sense, particularly as the mere maintenance of the Empire, with its garrisons and its bureaucrats, was so expensive. From the beginning of the second century AD, the State had to raise higher and higher taxes to maintain itself and its armies. It was under the Emperors Hadrian and Trajan, when the Empire was at its largest, that residual freedoms started to get knocked away to ensure that revenue was collected. Special commissioners, curatores, were appointed to run the cities. An army of secret police were recruited from the frumentarii. To pay for the extra bureaucrats, yet more taxes were raised, and the state increasingly took over the running of the economy – almost on ancient Egyptian lines. In AD 301, the Emperor Diocletian imposed fixed wages and prices, by decree, with infractions punishable by death. He declared that ‘uncontrolled economic activity is a religion of the godless’. Lanctantius wrote that the edict was a complete failure, that ‘there was a great bloodshed arising from its small and unimportant details’ and that more people were engaged in raising and spending taxes than in paying them. → Continue reading: Terence Kealey on the fall of the Roman Empire

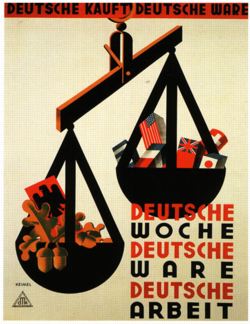

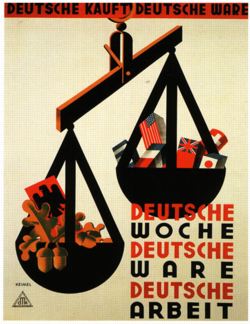

When reading about the many and disparate anti-globalisation activists who protest against international trade, one often gets the impression that the writers discussing their antics think that what motivates these folks is a relatively new phenomenon.

Not so. The desire to replace free trade with politically controlled and above all, domestic trade has long been a central aspect of collectivism of all flavours.

Adolf did not much care for global trade either

At its root, all forms of collectivism have more in common than its supporters might be comfortable admitting.

From the Radio Times (paper only) of 14-20 June 2003, on the subject of the BBC4 TV programme “High Rise Dreams”, shown on Thursday June 19th:

Time Shift looks back at how a group of idealistic architects changed the face of council housing in Britain, inspired by the modernist philosophy of Le Corbusier and new materials, only to be thwarted by financial restraints, poor craftsmanship and Margaret Thatcher’s private ownership creed.

In the Radio Times of 21-28 June 2003, on the subject of the repeat showing on BBC4 TV of the same programme on Sunday June 22nd:

In the first of three programmes on architecture, Time Shift looks at how idealistic architects changed the face of council housing in Britain, only then to be thwarted.

Well that removes the obvious political bias, but I’m afraid that if the idea was to make this puff less wrong-headed, it scarcely begins to deal with the deeper problems of it.

The implication, still being assiduously pushed on the quiet by the more blinkered sort of dinosaur partisan for the Modern Movement in architecture, is that the failures of the Modern Movement were all externally imposed, by penny pinching bureaucrats and by horrid, politically motivated politicians like the hated Margaret Thatcher, and that if only more money had been made available and they’d been allowed to get on with what they were doing unimpeded by their mindless enemies, all would have been well.

A logical (if not moral) equivalent would be if the Radio Times were to talk about how a group of idealistic Nazis tried to improve the world, inspired by the philosophy of Adolf Hitler, but about how they were thwarted (a) because not enough resources were devoted to doing Nazism, and (b) because Nazism’s opponents decided, for who-knows-what wrongheaded and arbitrary reasons, to barge in there and put a stop to it. With more money and less silly opposition from ideologically motivated enemies, all could – and would – have been well. (I dare say there are still a few old Nazis around who think this.)

The truth is that if (even) more money had been made available than was, the devastation cause by the Modern Movement in architecture in Britain would have been even more devastating.

The Modern Movement was animated by numerous seriously bad ideas (and by just sufficient good ones to make all the bad ones catch on seriously). It would require an entire specialist blog to do full justice to all these errors. I’ll end this post by alluding to just two such ideas, among dozens.

The Modern Movement is shot through with the idea that to put up an “experimentally designed” block of flats and immediately to invite actual people to live in it is a clever rather than a deeply stupid thing to do. Experimental-equals-good is the equation they swallowed whole. This is rubbish. Many experiments are excellent, as experiments. But what they mostly tell you, the way his numerous failed lightbulbs told Thomas Edison, is what not to do. Imagine if Edison had gone straight to production with his first idea of what a lightbulb might be. That was sixties housing in Britain. No wonder so much of it had to be dynamited.

The idea of a “vertical street”, also made much of by certain Britain’s Modern Movement architects, is also rubbish. Streets have to be at least a bit horizontal or they don’t work. Think square wheel.

I’ve chosen those two notions in particular because they were emphasised in the programme itself, the general tone of which was decidedly different from the puffs in the Radio Times.

I think I’ve found the culprit.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|