We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

I have long admired the libertarian historian and activist Stephen Davies, my previous posting here about him being this one, in connection with a talk he recently gave to Libertarian Home, in the superbly opulent setting of the Counting House‘s Griffin Room, in the City of London.

Here is a photo of Davies that I took that night:

Here is another, together with a photo of someone else also photoing him.

The Davies talk was predictably excellent, and this on a day when he had also given another talk elsewhere in southern England somewhere, to a bunch of sixth formers. I know this because I happened to share a tube journey with Davies afterwards, during which we talked about, among other things, his day, and why he was so very tired. I don’t recall where this other talk was, but do recall that it was definitely out of London and that Davies also organised for three other speakers to be present, as well as himself speaking. All this being part of the networking and speechifying enterprise that Davies masterminds from the IEA, along with his IEA colleague Christiana Hambro. LLFF2013 was but a London manifestation of a nationwide libertarian outreach programme.

The way Davies seems to operate is that he has a number of set-piece performances on particular themes, each of which he delivers pretty much off the cuff, with almost intimidating fluency but which he will typically have done several times before you get to hear it. So, when a particular audience assembles, they get to choose from a menu. There’s that history of libertarianism talk, which Davies did for Libertarian Home, having previously done it for the Essex University Libertarians and presumably for plenty of others besides. There is a healthcare talk, which I heard Davies do at LLFF2013, which he also did for those sixth-formers earlier in the day of the Libertarian Home performance. And there are several more of course, which I also asked him about, during that tube journey. I know. He was by then just about dead on his feet, but just sitting there and not asking such things would have felt even ruder than picking his exhausted brain.

A particular favourite of Davies himself, and of me now that I have heard about it, concerns history dates.

→ Continue reading: Steve Davies supplies some different and better history dates

Rob Fisher’s posting here a while back entitled Open source software v. the NSA reminded me that on April 26th, in my home, Rob Fisher gave a talk about open source software. I flagged this talk up beforehand in this posting, but have written nothing about it since. I don’t want to get in the way of whatever else Rob himself might want to write here on this subject, but I do want to record my appreciation of this talk before the fact of it fades from my faltering memory and I am left only with the dwindling remnants of what I learned from it.

My understanding of open source software, until Rob Fisher started putting me right, was largely the result of my own direct experience of open source software, in the form of the Linux operating system that ran on a small and cheap laptop computer I purchased a few years back. This programme worked, but not well enough. Missing was that final ounce of polish, the final five yards, that last bit of user friendliness. In particular I recall being enraged by my new laptop’s inability properly to handle the memory cards used by my camera. Since that was about half the entire point of the laptop, that was very enraging. I wrote about this problem at my personal blog, in a posting entitled Has the Linux moment passed?, because from where was sitting, then, it had. I returned with a sigh of relief to using Microsoft Windows, on my next small and cheap laptop.

I then wrongly generalised from my own little Windows-to-Linux-and-then-back-to-Windows experience, by assuming that the world as a whole had been having a similar experience to the one I had just had. Everyone else had, like me, a few short years ago, been giving Linux or whatever, a try, to save money, but had quickly discovered that this was a false economy and had returned to the fold, if not of Microsoft itself, then at least of software that worked properly, on account of someone having been paid to make it work properly.

The truth of the matter was clarified by Rob Fisher, and by the rest of the computer-savvier-than-I room, at that last-Friday-of-April meeting. Yes, there was a time a few years back when it seemed that closed source software looked like it might be making a comeback, but that moment was the moment that quickly passed. The reality was and remains that the open source way of doing things has just grown and grown. All that I had experienced was the fact that there has always been a need for computer professionals to connect computer-fools like me with all that open source computational power, in a fool-proof way. But each little ship of dedicated programming in each gadget floats on an ever expanding and deepening ocean of open source computing knowledge and computing power.

→ Continue reading: What I learned from Rob Fisher’s talk about open source software

As Perry de Havilland has just said, there is to be a Stephen Davies talk organised by Libertarian Home next Monday (June 17th), As Perry also said, several Samizdatistas will be attending, definitely including me.

By way of a further teaser, here is an interesting titbit of verbiage that I rather laboriously typed out recently, from an earlier talk that Davies gave, last October, at Essex University. I did Sociology at Essex University in the early 1970s, and I recently learned that there is now an Essex University Liberty League, who organised this Davies talk. We never had that in my day.

The complete talk lasts 46 minutes. Here, at 41:00, is what Davies says about how politics now is currently in a process of realignment. I don’t know if I entirely agree with him about this, but it certainly is an interesting idea:

I think that what we’re seeing at the moment is a major realignment in politics. We’re in the early stages of it, but I think it will be completed within the next decade or less.

For the last thirty or forty years, politics has essentially been about an argument between two large blocks, if you will, of voters and the politicians who represent them. On the one side you have people who combine social conservatism and traditionalism with free markets and support for limited government. Their opponents are typically people who are their mirror image. They are in favour of individual liberty in the social area, but they favour government activism in the economic area. What I think is happening – and this is not only happening in the UK; it’s happening is several other countries, in some it has already been realised, like Poland – what we’re seeing is a shift towards a different polarity underlying our politics, between on the one side more consistent libertarians – people who are consistently pro-liberty in the way that perhaps they were in the early to late nineteenth century, against government intervention in the economy but also in favour of individual liberty in other regards, and opposed also to aggressive state action at the global or international level, and on the other side people who are consistent authoritarians – people who favour large scale government intervention in the economy, and industrial policy for example, protectionism, things of that sort, a heavy degree of economic planning by the state, but who are also nationalistic and strongly socially conservative.

Watch, as they say, the whole thing. If you can’t watch the whole thing, at least watch from 41:00 to the end. Or not, as you please. It is, after all, about liberty.

If I know Simon Gibbs of Libertarian Home, which I do, this Stephen Davies talk next Monday will, like that Essex University Liberty League talk, be videoed. And if I know Stephen Davies, which I do, this talk next Monday will be a fascinating and excellent performance.

I’m guessing that the new talk may be covering similar ground to the one at Essex University, but for me this is a feature not a bug. I generally have to read or listen to things several times in order to absorb them properly. (Which is another reason why I am such a particular fan of repetition.)

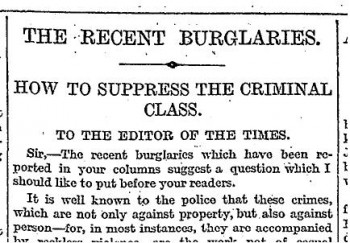

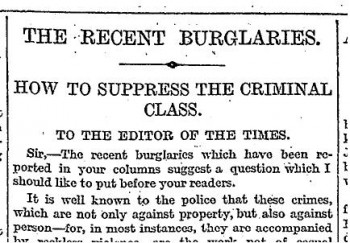

Take this letter to the Times from 2 June 1913:

I submit that the only effective way of dealing with these habitual and professional criminals is to expel them from the community against which they wager incessant war. A third conviction at assizes, or at quarter sessions, should entail the offender’s loss of personal liberty for the rest of his life. He should be deported to some island and reduced to a state of industrial serfdom…

To view the whole page it seems you have to click on the image, right click and select “Open image in new tab” and then zoom in. This is for Google Chrome. Other browsers may be different.

Within hours of the July 7 2005 bombings in London, the BBC stealth-edited its reports so that any references to “terrorists” that had initially appeared were changed to “bombers” or a similar purely descriptive, non-judgmental term. This was done in response to a memo from Helen Boaden, then Head of News. She did not want to offend World Service listeners. Given this reluctance to use the word “terrorist”, suspended for a few hours when terrorism came to its front door and then reimposed, I often wondered what it would take for the BBC to rediscover the ability to use words that imply a moral judgment.

One answer was obvious. It was fine to describe bombing as a “war crime” if it was carried out by the Israeli air force.

But in general as the years have gone by the BBC stuck to what it knew best: obfuscation. For instance, this article from last December, describing how fifteen Christians had their throats slit in Nigeria described the perpetrators as the “Islamist militants Boko Haram”. In venturing to describe the murders as a massacre, that article went further than most; the bombings of churches in Nigeria by Boko Haram are routinely described in terms of “unrest”, or as “conflict” – as if there were two sides killing each other at a roughly equal rate.

However, on Sunday I observed something I had not seen before. An atrocity carried out by Muslims against Christians was described as an “atrocity”. It happened in 1480, but still.

The BBC report says,

Pope Francis has proclaimed the first saints of his pontificate in a ceremony at the Vatican – a list which includes 800 victims of an atrocity carried out by Ottoman soldiers in 1480.

They were beheaded in the southern Italian town of Otranto after refusing to convert to Islam.

A reminder that “martyr” used to mean someone who died for his faith rather than killed for it. A reminder also of a centuries-long struggle against invading Islam that has been edited out of our history. You can bet the Seige of Vienna, which proved to be the high water mark of the Ottoman tide, does not feature in any GCSE syllabus. Nor does the rematch one and a half centuries later. The epic Seige of Malta was once celebrated in song and story, but don’t expect to see a BBC mini-series about it any time soon. Damian Thompson recently said a lot of what I had been thinking when he wrote about the the mass canonisation of the martyrs of Otranto in the Telegraph (subscription may be required):

Martyred for Christ: 800 victims of Islamic violence who will become saints this month

The cathedral of Otranto in southern Italy is decorated with the skulls of 800 Christian townsfolk beheaded by Ottoman soldiers in 1480. A week tomorrow, on Sunday May 12, they will become the skulls of saints, as Pope Francis canonises all of them. In doing so, he will instantly break the record for the pope who has created the most saints.

I wonder how he feels about that. Benedict XVI announced the planned canonisations just minutes before dropping the bombshell of his own resignation. You could view it as a parting gift to his successor. Or a booby trap.

The 800 men of Otranto – whose names are lost, except for that of Antonio Primaldo, an old tailor – were rounded up and killed because they refused to convert to Islam. In 2007, Pope Benedict recognised them as martyrs “killed out of hatred for the faith”. That is no exaggeration. Earlier, the Archbishop of Otranto had been cut to pieces with a scimitar.

Thompson continues,

There are, however, good secular reasons for welcoming this canonisation. Our history is distorted by a nagging emphasis on Christian atrocities during the Crusades combined with airbrushing of Muslim Andalusia, whose massacre of Jews in 1066 and exodus of Christians in 1126 are rarely mentioned. Otranto reminds us that Islam had its equivalent of crusaders – mighty forces who nearly captured Rome and Vienna.

The Muslim Brotherhood is still committed to a restored Caliphate; this week its supporters prophesied the return of a Muslim paradise to Andalusia. These are pipe dreams, it goes without saying. But they matter because they inspire freelance Islamists whose fascination with southern Europe has nothing to do with welfare payments. They think of it as theirs because they know bits of history that we’ve forgotten.

Our amnesia comes in handy in dialogue with Muslims: we grovel a few apologies for the Crusades, sing the praises of the Alhambra, and that’s it. But what does this self-laceration achieve? Arguably it’s counterproductive, because it shows Muslims that we’re ashamed of our heroes as well as our villains. Which is why the mass canonisation of 800 anonymous men is so welcome: it ensures that, even though the West has forgotten their names, it won’t be allowed to forget their deaths.

This made me laugh:

These expensive professionals seem to be very fragile creatures; the smallest hack, which no Public School boy would think of noticing, is enough to send them to earth in a well-acted, but supremely ridiculous, agony of pain, whereupon the referee blows his hard-worked whistle and hurries to soothe the injured spot with a sympathetic paw.

As you can probably tell from the language it’s from a while ago. 1913 to be exact and it’s from The Times’s report of that year’s FA Cup final. Yes, people then were making exactly the same complaints about footballers that they do now. At least they weren’t trying to eat one another.

What is really astonishing is the size of the crowd. 120,000 (the second highest ever) at Crystal Palace, of all places. I googled and found this photo from 1905:

What a mess! But as the article I linked to points out most of the crowd had no idea what was going on. Not only that but it was clearly a dangerous place to be:

Many of the railings designed to render the crowd of standing spectators less fluid and mobile collapsed with a crash, and there must have been scores of minor casualties.

Read the whole thing as they used to say.

Today I received one of those collective emails with a big list of recipients at the top. It was from Tim Evans to the Essex University Liberty League, and copied to the rest of us, suggesting all the copyees as potential speakers to the Essex University Liberty League. I was pleased to be even suggested, because I was a very happy student at Essex University in the early 1970s. Fingers crossed, hint hint.

But much more importantly, following a little googling for the Essex University Liberty League, I found my way to this, which I had not noticed before and which is a video of a talk given by the noted libertarian historian Stephen Davies to … the Essex University Liberty League. Having both hugely enjoyed and been hugely impressed by the talk that Stephen Davies gave to the Liberty League Freedom Forum in London just under a fortnight ago, on the subject of healthcare, I cranked up this video about the history of British libertarianism and had a listen.

Brilliant. The time, nearly fifty minutes of it, just flew by. Davies really is a master communicating a large body of ideas and information, seemingly with effortless ease, in what is (given the sheer volume of all those ideas and all that information) an amazingly short period of time, although in other hands the same chunk of time would feel like an eternity.

Thank goodness cheap videoing arrived in time for Davies to be extensively captured on it, for two reasons. First, it would be very hard to take notes that would do justice to a Stephen Davies talk, and it would be impossible to remember it all. There is, every time, just too much good stuff there. You want to be able to hear it all again, with a pause button available. Second, I get the distinct impression that Davies knows a great deal more about the present and the past of the world, and of the people trying to make the world more liberty-loving, than he has so far managed to get down on paper. Indeed, I sense that Davies’s recent IEA job, stimulating Britain’s student libertarian network, is a calculated trade-off on his part, between one important job, namely that, and the other important thing that Davies ought to be doing, namely writing down many more of his brilliant thoughts and discoveries and opinions and historical wisdoms than he has so far managed to write down.

Although, now would be a good time to flag up a piece Davies wrote for the Libertarian Alliance entitled Libertarian Feminism in Britain, 1860-1910, which is about the kind of thing his talk is about. The point being that most feminists then were libertarians, in contrast to the collectivists that most feminists are now. So, Davies has written some of his wisdoms down, just not as much as he might have.

However, meanwhile, and as a natural consequence of all the student networking that he has lately been doing, Davies does often give a talk, and sometimes someone records it. Like I say, thank goodness for video. And congratulations to whoever did video this particular Davies talk to the Essex University libertarians. Richard Carey, who did the short blog posting where I found the video, does not say who did this. Presumably an Essex libertarian. As I say, kudos to whoever it was.

Sadly, the Stephen Davies talk to LLFF2013 about healthcare was not videoed.

Indulge me in a little sermon. The tradition among many anthropologists and archaeologists has been to treat the past as a very different place from the present, a place with its own mysterious rituals. To cram the Stone Age or the tribal South Seas into modern economic terminology is therefore an anachronistic error showing capitalist indoctrination. This view was promulgated especially by the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, who distinguished pre-industrial economies based on ‘reciprocity’ from modern economies based on markets. Stephen Shennan satirises the attitude thus: ‘We engage in exchanges to make some sort of profit; they do so in order to cement social relationships; we trade commodities; they give gifts.’ Like Shennan, I think this is patronising bunk. I think people respond to incentives and always have done. People weigh costs and benefits and do what profits them. Sure, they take into account non-economic factors, such as the need to remain on good terms with trading partners and to placate malevolent deities. Sure, they give better deals to families, friends and patrons than they do to strangers. But they do that today as well. Even the most market-embedded modern financial trader is enmeshed in a web of ritual, etiquette, convention and obligation, not excluding social debt for a good lunch or an invitation to a football match. Just as modern economists often exaggerate the cold-hearted rationality of consumers, so anthropologists exaggerate the cuddly irrationality of pre-industrial people.

– This little “sermon” is on pp. 133-4 of The Rational Optimist by Matt Ridley (also quoted in this earlier posting here), in the chapter about the simultaneous rise of agriculture and early industrial specialisation, all within the context of a wider web of exchange relationships. What most clearly distinguishes humans from animals, and successful humans from all the failures, says Ridley, is trade.

Early agriculture and early industrial specialisation are both manifestations of the division of labour, which depends on trade. You can’t have early agriculture without specialists supplying crucial agricultural implements, such as axes to clear forests. You can’t have specialist suppliers of agricultural implements without specialist food-growers feeding them.

“William Shakespeare evaded tax and illegally stockpiled food during times of shortage so he could sell it at high prices, academics have claimed“.

Last night being the last Friday of March, there was a meeting at my place, as already flagged up here. But it was also Good Friday, so I did a bit of extra hustling and emailing around beforehand to ensure some kind of turnout. It worked. Great talk, and there were nine libertarian-inclined Londoners present in the form of: two Americans, a German, a Frenchman, a Spaniard, a New Zealander and three Englishmen.

I neglected photography at the January meeting, which I already regret, and did hardly any better at the end of February. This time I tried harder, this being one is my favourite snaps from last night:

Those are two of the three Englishmen who were present, the other being me. On the right there is speaker for the evening Richard Carey, and on the left Simon Gibbs, both of Libertarian Home fame. Gibbs was not rudely ignoring the conversation and catching up on his emails; he was looking up names and titles that were being mentioned in the conversation. I particularly like the potato crisp in Carey’s left hand at the very bottom of the picture.

The talk was everything that I personally was hoping for. There was lots of biographical detail of who the key early Austrians were (Menger, Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser) and what kind of intellectual context they were operating in and what they said. And then the same for the later figures of note (von Mises, Rothbard). Other twentieth century figures were mentioned. Given how admiringly Carey spoke about him, I was particularly intrigued by Frank Fetter, only a name to me until now.

Carey made no attempt to disguise the fact that he is a recent arrival to the task of getting his head round Austrian Economics, which for me was a feature rather than a bug, just as I thought it would be. And he made no attempt to suggest that he understood more than he actually did about the subject. His talk entirely lacked that sub-agenda that you so often sense with some speakers, that half the point of telling the story is to tell the story, but the other half of the point is to prove how very clever and well informed the speaker is, more so than he actually is. That Carey had no time for such nonsense only made me admire his intellect all the more.

I had been expecting that the abstract theorising about what it all meant, what the intellectual guts of it all consisted of, would come at the end. The economic way of getting stuff versus the political way, trade versus stealing, individualism versus collectivism, the subjectivity of value, and so forth. Actually that bit came, at some length, at the beginning, so much so that I at first feared that all that biographical detail that I had been so looking forward to would be somewhat skated over. But all ended well, and I learned a great deal.

I did not record this talk in any way. However, Simon Gibbs, the man on the left in the picture above, has already invited Richard Carey to do a repeat performance of this talk for Libertarian Home, and a video camera will presumably then be running. Meanwhile, I am very happy for Carey to have given this talk a first outing in friendly surroundings, and for him to get some early feedback on it. I find that I am making a point of getting speakers to speak about things they’ve not spoken about before, but will undoubtedly be speaking about again, for just these sorts of reasons.

Two books were mentioned in the course of the discussion afterwards that I intend to investigate further.

Christian Michel mentioned this collection of lectures by Michel Foucault, in one of which he apparently said something embarrassingly (given the kind of people who were listening) nice about the free market as the only place where freedom actually happens, or some such surprising thing. I’ve already emailed Christian asking for chapter and verse of the quote in question.

And second, Aiden Gregg (who is an academic psychologist and who has already been fixed to speak at a later one of these meetings) mentioned the writings of somebody called Larken Rose, a new name to me, and in particular this book, which appears to cover similar ground, albeit in a somewhat different style, to that discussed in Michael Huemer’s The Problem of Political Authority, which has been written about here recently.

Evenings like this don’t have any immediate world-changing impact, but every little helps.

One many significant dividing lines between, on the one hand, enthusiasts for free economies and free societies, and on the other hand those who favour a large role for the state in directing and energising society, concerns where you think art and science come from.

Those looking for an excuse to expand the role of the state tend to assume that art and science come from the thoughts and actions of an educated and powerful elite, and then flow downwards, bestowing their blessings upon the worlds of technology and entertainment, and upon the world generally. Science gives rise to new technology. Art likewise leads the way in new forms of entertainment, communication, and so on.

While channel surfing a while back, I heard Dr Sheldon Cooper, the presiding monster of the hit US sitcom The Big Bang Theory, describe engineering as the “dull younger brother” (or some such dismissive phrase) of physics. The BBT gang were trying to improve their fighting robot, and in the absence of the one true engineer in their group (Howard Wolowitz), Sheldon tries to seize the initiative. “Watch and learn” says Sheldon. Sheldon’s attitude concerning the relationship between science and technology is the dominant one these days, because it explains why the government must pay for science on the scale that it now does. Either governments fund science, or science will stop. Luckily governments do now fund science, so science proceeds, and technology trundles along in its wake. Hence modern industrial civilisation.

If the above model of how science and art work was completely wrong, it would not be so widely believed in. There is some truth to it. Science does often give rise to new technology, especially nowadays. Some artists are indeed pioneers in more than art. But how do science and art arise in the first place?

Howard Wolowitz is the only one of The Big Bang Theory gang of four who does not have a “Dr” at the front of his name. But he is the one who goes into space. He builds space toilets. He was the one who actually built the fighting robot. Dr Sheldon Cooper, though very clever about physics, is wrong about technology, and it was good to see a bunch of comedy sitcom writers acknowledging this. After “Watch and learn”, Sheldon Cooper’s next words, greeted by much studio audience mirth, are “Does anyone know how to open this toolbox?”

→ Continue reading: Some thoughts about where science and art come from (and about why governments don’t need to pay for either of them)

The Times, Tuesday, Feb 25, 1913; pg. 10. Click to enlarge

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|