We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

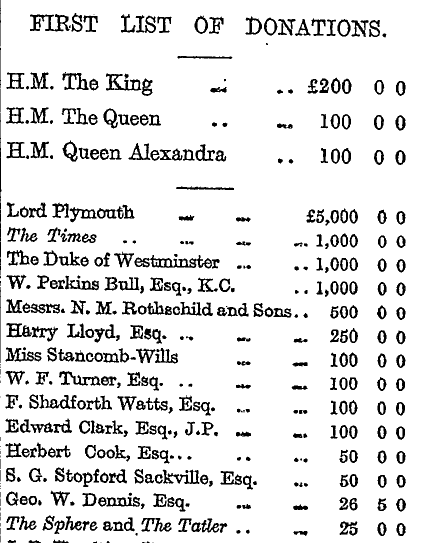

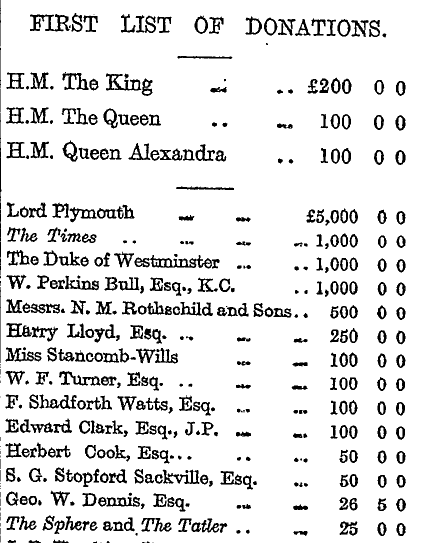

Here’s the situation. It’s 1913 and the owners of the Crystal Palace need to sell it. Lord Plymouth has agreed to temporarily save it for the nation by ponying up the asking price (£230,000 in 1913 money – £46m in today’s if you convert to and from gold.) The deal is that if a fund can pay him back then the Palace will be “saved for the nation” and if not it will be saved for the builders.

The City of London and the nearest councils to the Palace have agreed to pay for half of it. Now, it is up to the general public and The Times. And this is how they are going to get people to cough up: the subscription list.

The Times, 2 July 1913 page9 It’s rather clever. Whether you think preserving the Crystal Palace is a good idea or not, if your peers do, you’d better pay something. And it had better be a reasonable amount or else they’ll think you’re a skinflint. This is a very common way of raising money. My mother tells me that this is how they used to raise money for her local church. One wonders why the technique fell into disuse.

The necessary funds were secured in slightly less than a fortnight and the Crystal Palace continued to stand in Crystal Palace until it was wrecked by fire in 1936.

The other thing that really got me thinking was seeing the sort of people that would appear on television, proselyting about the coming tragedy that it would imminently become too late to prevent. Whether from charities, pressure groups or the UN, I knew I had heard their strident and political use of language, and their determination to be part of the Great Crusade to Save the World before. These were the CND campaigners, class war agitators and useful fools for communism in a new guise. I suddenly realised that after the end of the Cold War, rather than slinking off in embarrassed fashion to do something useful, they had latched onto a new cause. The suggested remedies I heard them espouse were always socialist in approach, requiring the installation of supra-national bodies, always taking a top-down approach and furiously spending other peoples’ money. They were clearly eager participants in an endless bureaucratic jamboree.

Now don’t get me wrong: a scientific theory is correct or not regardless of who supports it. But recognising the most vocal proponents of CAGW for what they were set alarm bells ringing, and made me want to investigate further…

– Jonathan Abbott writes on WUWT about his personal path to C(atastrophic) A(nthropogenic) G(lobal) W(arming) skepticism.

Aside from the slightly odd word “proselyting” … snap.

A few commenters here have expressed boredom about this whole climate thing, and a lot of people certainly are very bored indeed with the climate alarmists. But when you consider how much power and money are still being diverted into arrangements based on climate alarmism being true, by people for whom the science still seems to be settled like it was 1999, it would surely be a big mistake to stop discussing these matters now. This would be the equivalent, during the Cold War (an earlier huge argument to which Abbott rightly compares the climate debate), of reading someone like Von Mises explaining in about 1950 that communism is economically irrational and hence in the long run doomed, and saying, right, we can forget about that then. Communism still had many decades of damage to do. And it didn’t just fall. It was also pushed. Climate alarmism is the same now. The damage it will do has, arguably, only just begun. Just how much damage climate alarmism ends up doing depends on how much it continues to be challenged.

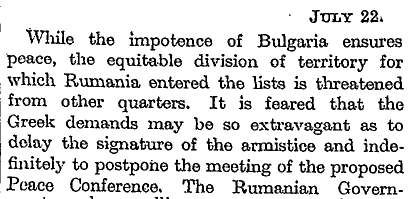

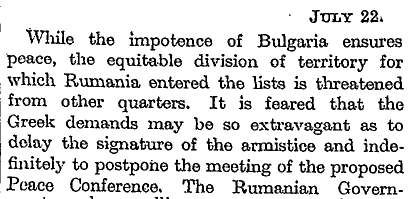

I do not claim to be an expert on the Balkan Wars which were fought in 1912 and 1913. If I understand correctly, in the First Balkan War Turkey was almost completely thrown out of Europe while in the second Bulgaria embarked upon a war of conquest and ended up with rather less than she’d started with.

The Times 23 July 1913 p8 The significance of all this, as Eric Sass points out, lay in how it altered Russia’s relationship with Serbia. Russia, Serbia and Bulgaria were Slavic states. Russia, being the biggest, wanted to be the leader. Serbia and Bulgaria, being small wanted Russian protection. So, when a dispute rose over the borders between them the two small states submitted their dispute to the big one. When Bulgaria failed to get what she wanted she went to war.

Defeat led to Bulgaria allying herself with Austria-Hungary while Russia responded by allying herself ever more closely with Serbia. Hence, perhaps, the robustness of Russia’s response to Austria’s declaration of war against Serbia in 1914.

Update For a while now I’ve been in the habit of linking to the whole page rather than just the article. This has been to give readers the chance to see what else was making the news at the time and, perhaps, to find something just as bloggable. Well, it appears Simon Gibbs has done just that.

Guy Lodge and Jessica Asato looked ahead ten years, ten years ago.

Imagine it’s 2013 and the pendulum of the electoral cycle has finally swept the Labour Party out of office. What might be the legacies of three terms of a New Labour government and what would be the direction of the Labour Party in opposition?

Contrary to expectations, Labour’s record on public services will be quite good. In health, waiting lists will be practically non-existent, patients will be able to choose when to see their GP and where to go to hospital, and towards the end of the third term the recruitment drives of the early 2000s will pay off as shortages of key medical staff begin to ease.

….

It will be widely thought that the Labour Government missed a key opportunity to totally reshape the life opportunities of children by failing to introduce universal childcare and early years education, despite the obvious success of SureStart.

….

The main achievement in foreign policy for Labour will be membership of the Euro; narrowly won after holding a referendum on the back of a third term win. The EU will also agree to reform the Common Agricultural Policy after successful campaigning by an ever-growing trade justice movement supported by the UK government. Disparities between economic growth in developing and rich countries will continue to widen, however, and peacekeeping and conflict resolution will become more important as global insecurity escalates. Global warming and sustainability will also begin to make more of an impact on the public’s consciousness forcing Labour to rediscover its environmental soul.

….

The Labour Party will still be going strong in 2013, though radically altered in outlook and shape. With EU enlargement transnational political parties might be established, sharing ideals in common at the European level, but acting independently at home. If Labour were to eventually split with the unions over public service modernisation, state funding of political parties would become necessary and the character of the party would change.

That last line might yet prove to be a quite good prediction.

In 2003 Guy Lodge was Chair of the Young Fabians and Jessica Asato was a researcher at the Social Market Foundation. Nowadays Guy Lodge is Associate Director for Politics and Power at the IPPR thinktank and Jessica Asato is prospective Parliamentary candidate for Norwich North and political adviser to Tessa Jowell MP.

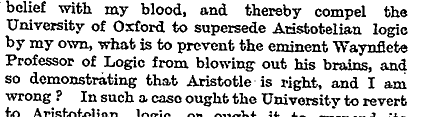

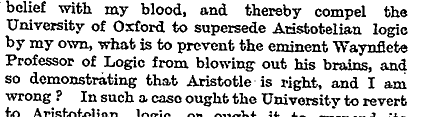

George Bernard Shaw was a playwright. He was also a supporter of Stalin. Therefore, it’s always amusing to see people poking fun at him. Here is one Charles Mercier responding to Shaw shortly after Emily Davison was trampled to death at the Derby:

The Times, 4 July 1913 p4 (right click to see original) If I understand Mr Bernard Shaw aright, his contentions are two – first, that a martyr is a person who seals his belief with his blood; and, second, that if a person seals his belief in his blood, we ought at once to adopt that belief, or at least act as if it were true. “Sealing one’s belief with one’s blood” is a picturesque expression which has always hitherto been understood to mean choosing the alternative of death when we are compelled to choose between death and abandoning, or pretending to abandon, a belief. No one offered this choice to Miss Davison, and in this sense she certainly did not seal her belief with her blood, and was not a martyr. Mr Shaw would extend the expression to the act of committing suicide in order to demonstrate the truth of a belief; and his opinion seems to be that, if a person offers this proof of the truth of any belief, we ought to act as if the belief were true. There seems to me to be a flaw in his reasoning, and the practice would be inconvenient.

I, for instance, have a settled and profound conviction that Aristotle’s logic is utterly erroneous, and that my own system is immeasurably superior to it, but if I cut my throat in order to seal this belief with my blood, and thereby compel the University of Oxford to supersede Aristotelian logic with my own, what is to prevent the eminent Waynflete Professor of Logic from blowing out his brains, and demonstrating that Aristotle is right, and I am wrong? In such a case ought the University to revert to Aristotelian logic, or ought it to suspend its judgement until Professor Schiller, who agrees with me, drowns himself in the Cherwell? It seems to me that if Mr Bernard Shaw’s doctrines are carried into practice they will lead to the sacrifice of many useful lives with but little compensating advantage. If, however, he really holds these opinions with the fervour that his expression of them seems to indicate, he has himself shown the proper way to impress them on the community, a way that I hesitate to commend to him, lest I should find myself in the unpleasant position of an accessory before the fact to a felony.

In those days suicide was a crime.

Much as this is amusing there is a flaw: George Bernard Shaw didn’t actually say it.

First I read Leo McKinstry’s Boycott book, and loved it. Then I read his Spitfire book, and liked that a lot also. But while reading Spitfire, I thought to myself that what I would also like to read – would really like to read – would be a book by Leo McKinstry about the Avro Lancaster, the big four-engined bomber that inflicted most of the British bomber damage on the cities of Germany during the latter half of World War 2. The Lancaster was one of my favourites during my Airfix years. Seeing a real live Lancaster flying at Farnborough in the summer of 2010 made me even more curious about this famous airplane. The more I thought about it, the more I realised how ignorant of the Lancaster’s history I was. So when McKinstry obliged with Lancaster, I did not hesitate. I bought it, and devoured it.

Ever since doing that, I have been meaning to write about this book here, but I never got around to finishing what I started. So instead of trying to say everything I might want to say about this excellent book, I will instead now focus mostly on the most interesting thing among many interesting things that I learned from reading Lancaster. I will focus on what a very strange birth the Avro Lancaster had.

In the late 1930s, believing that bombers would always get through and that they therefore had to have lots of bombers or lose the war, British Air Officialdom had two ideas about how to build a bomber. They accordingly announced two specifications, which different potential bomber-makers were invited to meet with their designs. They wanted a two engined bomber, like those that the Germans bombed Britain with in 1940 but better, or like the Wellington but better. And they wanted a much bigger four engined bomber, such as the Germans never got around to building, and like … well, like the Avro Lancaster.

So, the Lancaster was Avro’s answer to the second requirement? Actually, no. Or, not at first. Britain ended up with three four-engine heavy bombers, the Short Stirling, the Handley Page Halifax, and the Lancaster. But strangely, by far the worst of these three, the Short Stirling, was the only one of the three that was all along intended to be a four-engine bomber. Both the Halifax and the Lancaster started out as answers to the two-engine specification rather than the four-engine one.

This strangeness was caused by Rolls Royce then being engaged in producing two engines, the Merlin and the Vulture. The Merlin was proving itself to be very good (arguably it became the greatest single piece of mechanical kit of the entire war), but the Vulture was only revealing itself to be terrible. The idea was that the Vulture would power the two-engined bombers. But, with the Vulture already looking so bad, Handley Page quickly got permission to change their Vulture-powered two-engine bomber into a Merlin powered four-engine bomber. They switched specifications, in other words.

Avro persisted with their two-engine design, the Manchester, and Air Officialdom, in addition to ordering lots of Halifaxes, also ordered two hundred Manchesters to be made, long before they could be sure that it was a good airplane. Soon, they upped the order to over a thousand. Despite the Manchester being, to put it mildly, unproven, Avro started manufacturing them.

But the Manchester was a clunker. It was slow. It couldn’t carry many bombs. It handled abominably. It was a death trap. The pilots hated it. Avro did everything they could to make the Manchester work, but it never did, not least because Rolls Royce were never able to make much of their Vulture. As the Merlin began to prove itself to be the Merlin, Rolls Royce understandably concentrated on that.

At which point, in 1940, Avro proposed the Halifax solution to the Manchester problem. Turn the Manchester from a Vulture-driven two-engine bomber into a Merlin-driven four-engine bomber. Avro dramatically illustrated this idea when they showed a model of a Manchester to a visiting party of Air Officialdom. Right in front of their little audience of grandees, they took off the Manchester’s wings and shoved on different and bigger wings with two more engines attached to them. That, said Avro, is what we should be building.

→ Continue reading: The strange birth of the Avro Lancaster

By the time he gets to foreign policy, Rothbard has been on such a jihad against the state, and the U.S. government in particular, that he goes berserk and accuses the United States of being the bad guys in the (then ongoing) Cold War. In the First Edition (1973) he went so far as to attribute to Stalin a libertarian foreign policy, alleging the USSR practiced non-interventionism. When it was pointed out to him that the USSR invaded Finland, Rothbard added to his Second Edition a defense of Stalin’s attack, arguing that Stalin only wanted to reclaim traditionally Russian Karelia and liberate all the Russians supposedly living there. All of that is a-historical nonsense and Rothbard simply invented it. The Soviets planned to capture all of Finland and had even assembled a new Marxist government they hoped to install in Helsinki. The areas Stalin invaded are not “traditionally Russian.” But even if Rothbard’s interpretation were true, how can Rothbard justify on libertarian grounds the bloodiest dictatorship in history attacking a free country in an effort to get “its” land and people back? It makes no sense, but Rothbard’s only concern is to defend his indefensible claim that the United States surpasses the rest of the world in doing evil. Unfortunately for Rothbard, long before the First Edition came out there was ample evidence that the Stalin and other Soviet leaders engaged in interventionism all around the world, often quite bloodily (Katyn Forest anyone?) Rothbard’s “libertarian” defense of Stalin is despicable and intellectually dishonest — and that’s the real problem with this book. Rothbard pretends that he’s doing careful analysis and finds the state wanting while showing that his own anarcho-capitalist system shines. But in fact, no argument is so bad, no intellectual sleight-of-hand too dishonest, if it will get Rothbard to his pre-chosen conclusion.

Charles Steele.

How often do we see the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” error among even pretty smart people – and Rothbard was not a stupid man. I have come across some libertarians who, out of an entirely rational desire to be wary of state adventurism, moral panics and so on, bend over backwards to play down threats and problems that statists talk about even when those threats and problems might actually be real. (This can be seen sometimes on issues such as Islamic terrorism or, for that matter, on environmental issues.) This can undermine the credibility of the argument. Far better for the libertarian to say: “Yes, I agree that X or Y is serious and cannot be ignored but a free society such as the one I favour is a far better position to deal with it than your Big Government-model one.”

Rothbard, it also should be said, was also an enthusiastic stirrer and practical joker: I think he enjoyed being outrageous for the sake of being outrageous; his pranksterism sometimes became an end in itself. (Sometimes those on the receiving end deserved it.) But this sort of behaviour carries its costs. It also leaves one with a sneaking sense that the joker might use the “but I was only joking!” defence as a ploy in case he or she was actually serious.

As Charles Steele writes in the same piece, this is all a great shame given that Rothbard could also be right on a lot of issues. I can recommend Brian Doherty’s Radicals For Capitalism, which gives Rothbard a lot of detailed treatment.

I think it was Rothbard who once came out with the crackerjack line: Say what you like about Marx, but at least he wasn’t a Keynesian.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

– from a document that may soon be given a security classification the way things are going. Simply following that link could brand you as a potential terrorist. Not to mention get you in trouble with the IRS.

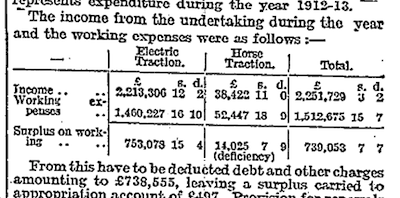

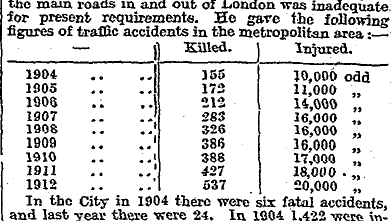

A hundred years ago, London was undergoing a transport revolution. Electric trams, electric underground trains, motor cars and motor buses had all entered the market while horse-drawn buses, trams and cabs were leaving it. I’m guessing here, but it seems to me that for centuries the big class distinction was whether you owned a horse or not. Now that horses were becoming uninimportant, class barriers were starting to come down.

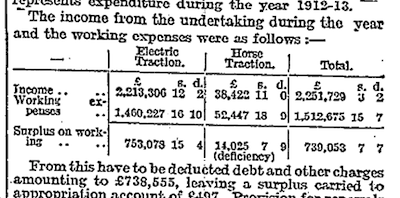

But that’s by the by. In a revolution there are winners and losers. And here, in the London County Council’s accounts, we see a loser, horse-drawn trams:

The Times 16 June 1913 page 3 But read a bit further and you see it’s not just horse-drawn trams that are losing out:

The most striking feature of the accounts is the falling off in gross traffic receipt, as well as in the receipts a car-mile compared with previous years. The average passenger receipts a car-mile have gradually fallen from 11.95d. in 1907 to 9.73d. this year. A new factor which has arisen during the last year or two which the Council has seriously to reckon, in its efforts to maintain the tramway undertaking on a sound financial basis, is the great increase in the competition which the tramways have to meet from the motor-omnibus undertakings.

In other words buses are taking their market. I must admit I’m in two minds on this. On the one hand, it’s hard to feel sympathy for the government losing money. On the other, trams are nicer than buses: smoother, quieter, cleaner. And commercial tram operators (they do exist) will not find bus competition any easier to deal with. You have to feel some sympathy with operators that have, at great expense, set up electric tram systems only to find them superseded by the internally combusted upstart within a few years.

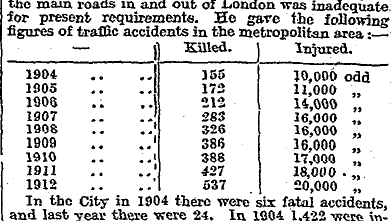

But buses are where the action is. Still. In 1911, they bought up the lion’s share of London’s tube network. [Yes, private enterprise integrated transport.] They may be dirty, noisy and uncomfortable but they are cheap and flexible and go where people want them to go. Oh, and dangerous. Did I mention dangerous:

The Times 20 June 1913 page 4

Back in 1913, the Times has just published a supplement on the textile industry. Just about every company that has advertised has included a picture of its factory.

For example:

I think they look fantastic: big, modern, solid, clean even. But why are they used in adverts? Perhaps the question should be why companies don’t use them any more? What it does suggest is that at the time they were regarded as far from the dark, satanic mills of modern-day folklore.

I have long admired the libertarian historian and activist Stephen Davies, my previous posting here about him being this one, in connection with a talk he recently gave to Libertarian Home, in the superbly opulent setting of the Counting House‘s Griffin Room, in the City of London.

Here is a photo of Davies that I took that night:

Here is another, together with a photo of someone else also photoing him.

The Davies talk was predictably excellent, and this on a day when he had also given another talk elsewhere in southern England somewhere, to a bunch of sixth formers. I know this because I happened to share a tube journey with Davies afterwards, during which we talked about, among other things, his day, and why he was so very tired. I don’t recall where this other talk was, but do recall that it was definitely out of London and that Davies also organised for three other speakers to be present, as well as himself speaking. All this being part of the networking and speechifying enterprise that Davies masterminds from the IEA, along with his IEA colleague Christiana Hambro. LLFF2013 was but a London manifestation of a nationwide libertarian outreach programme.

The way Davies seems to operate is that he has a number of set-piece performances on particular themes, each of which he delivers pretty much off the cuff, with almost intimidating fluency but which he will typically have done several times before you get to hear it. So, when a particular audience assembles, they get to choose from a menu. There’s that history of libertarianism talk, which Davies did for Libertarian Home, having previously done it for the Essex University Libertarians and presumably for plenty of others besides. There is a healthcare talk, which I heard Davies do at LLFF2013, which he also did for those sixth-formers earlier in the day of the Libertarian Home performance. And there are several more of course, which I also asked him about, during that tube journey. I know. He was by then just about dead on his feet, but just sitting there and not asking such things would have felt even ruder than picking his exhausted brain.

A particular favourite of Davies himself, and of me now that I have heard about it, concerns history dates.

→ Continue reading: Steve Davies supplies some different and better history dates

Rob Fisher’s posting here a while back entitled Open source software v. the NSA reminded me that on April 26th, in my home, Rob Fisher gave a talk about open source software. I flagged this talk up beforehand in this posting, but have written nothing about it since. I don’t want to get in the way of whatever else Rob himself might want to write here on this subject, but I do want to record my appreciation of this talk before the fact of it fades from my faltering memory and I am left only with the dwindling remnants of what I learned from it.

My understanding of open source software, until Rob Fisher started putting me right, was largely the result of my own direct experience of open source software, in the form of the Linux operating system that ran on a small and cheap laptop computer I purchased a few years back. This programme worked, but not well enough. Missing was that final ounce of polish, the final five yards, that last bit of user friendliness. In particular I recall being enraged by my new laptop’s inability properly to handle the memory cards used by my camera. Since that was about half the entire point of the laptop, that was very enraging. I wrote about this problem at my personal blog, in a posting entitled Has the Linux moment passed?, because from where was sitting, then, it had. I returned with a sigh of relief to using Microsoft Windows, on my next small and cheap laptop.

I then wrongly generalised from my own little Windows-to-Linux-and-then-back-to-Windows experience, by assuming that the world as a whole had been having a similar experience to the one I had just had. Everyone else had, like me, a few short years ago, been giving Linux or whatever, a try, to save money, but had quickly discovered that this was a false economy and had returned to the fold, if not of Microsoft itself, then at least of software that worked properly, on account of someone having been paid to make it work properly.

The truth of the matter was clarified by Rob Fisher, and by the rest of the computer-savvier-than-I room, at that last-Friday-of-April meeting. Yes, there was a time a few years back when it seemed that closed source software looked like it might be making a comeback, but that moment was the moment that quickly passed. The reality was and remains that the open source way of doing things has just grown and grown. All that I had experienced was the fact that there has always been a need for computer professionals to connect computer-fools like me with all that open source computational power, in a fool-proof way. But each little ship of dedicated programming in each gadget floats on an ever expanding and deepening ocean of open source computing knowledge and computing power.

→ Continue reading: What I learned from Rob Fisher’s talk about open source software

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|