We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, II, IV, V & VI.

Politically, these are radical times. In 1906 a Liberal government was returned by a landslide.

Elections in those days were very different from the way they are today. For starters, the electorate was much smaller. Women couldn’t vote at all and men had to be over 21 and pass a not particularly onerous property qualification. General elections themselves, took place over the course of a couple of weeks. In each constituency the voting would take place over a number of days and it would not be the same days in each constituency. As a consequence the results would filter in over the course of a week.

Up until 1910, MPs weren’t paid at all. If they wanted to become a minister they would have to resign their seat and fight a by-election.

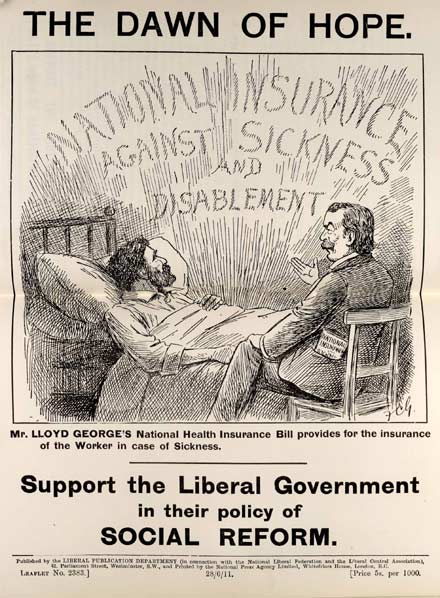

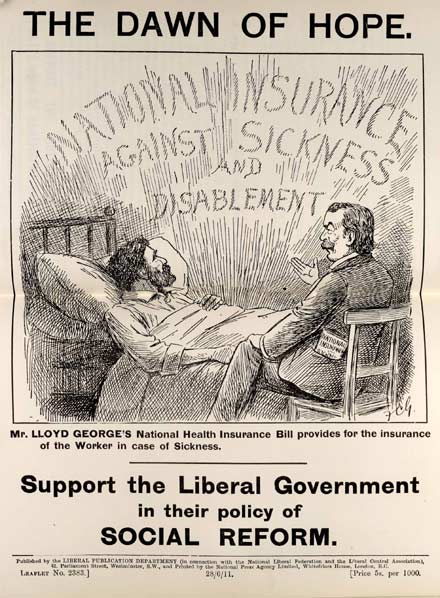

The Liberal government introduced the Workmen’s Compensation Act, old-age pensions, sick pay, unemployment benefit for certain trades, maternity benefit, nationalised GPs, allowed Trade Unions to pay strike pay and, as I mentioned earlier, nationalised the telephones. To pay for it all they upped taxes. At this point the Unionist-dominated House of Lords objected causing a constitutional crisis. After two general elections in 1910 and a threat to create 1000 new peers the Lords’ backed down and their power to block money bills was removed for good.

Sick pay is not working particularly well. In the days when sick pay was entirely in the hands of friendly societies they had powerful incentives to make sure that people claiming sick pay were indeed sick as indeed did the doctors in their pay. Now that the state bears the costs you will be shocked to hear that there has been a dramatic increase in the number of people claiming sickness benefit. Malingerers, as they are known can get away with it because doctors are signing them off as sick without making a proper examination.

In 1910 the Liberals lost their majority and went into coalition with Labour and the Irish Nationalists (one of whom, incidentally, represents a constituency in Liverpool). The price of Nationalist support is Home Rule and the obstacle to that, as always, is Ulster. In the North, men are drilling and guns are being run. The Unionists are in the process of setting up a provisional government. The penny is beginning to drop that this could end in Civil War.

The suffragettes are causing chaos. They are breaking windows, destroying mail, disrupting political meetings, and burning down country houses. When jailed they go on hunger strike. Initially, the state force fed them. When this proved unpopular it started releasing them when they became weak and re-imprisoning them when they’d become stronger. Known as the Cat and Mouse Act it simply proves that the state has no idea what to do.

It could of course give women the vote. A bill was introduced in May 1913 but mysteriously failed to pass. While arguing against it, the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith amid much tedious inconsequential waffle argued that the bill would enlarge the franchise both too much and too little and therefore, it should be rejected.

What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, III, IV, V & VI.

Little is said about the economy – not that that was a term in common use at the time. Unemployment – known as idleness – seems non-existent but there is some inflation – referred to as an “advance in prices” or “an increase in living costs”. Seeing as the pound was tied to gold at a rate of about £4 per troy ounce this seems surprising although the enormous gold finds in South Africa may have had something to do with it. Inflation may have been the cause of the many strikes at the time and it may have been the effect. The tax take is about 10%. Today it is over 40%. Northerners are better off than Southerners.

In 1912 the Titanic, the largest moving object in the world, set sail on its maiden voyage. Most people are aware that it sank, which is notable enough. But the really amazing part is that it got out of port at all. There had been a month-long national coal strike immediately beforehand and supplies were extremely low. Strikes are extremely common. In addition to the national coal strike, recent years have seen a national rail strike, a London dock strike and a Hull dock strike. London is currently undergoing a painters and decorators’ strike and Dublin a tramworkers’ strike.

In a previous coal strike, in 1910 in South Wales, troops had been used to put down a riot. At about the same time troops were also used to put down a riot in Liverpool.

The state is starting to nationalise things. In 1911 it nationalised the National Telephone Company. I should explain that this isn’t quite as dramatic as it sounds. The state already owned the trunk lines. The National Telephone Company owned everything else and operated them under licence. In 1911 the licence simply wasn’t renewed. In London, the County Council, late in the day, built an electric tram network. It was completed just in time for motor buses to take their market away from them.

It is difficult to detect any class, race or sex prejudice in the pages of the Times.

In 1913, the world is undergoing a transportational revolution. The horse is being swept from the streets of London to be replaced by electric trams, motor buses, motor lorries and motor cars. Below the streets, the deep-level, electrified tube lines are being built while steam trains are being replaced by electric ones on the older cut and cover lines. We are seeing the beginnings of surburban electrification.

Buses, in particular, are allowing people to travel much further to work and to shop. The only downside is that a lot of people are getting killed on the road.

Talking of buses, this is still a time when entrepreneurs are able to think big. Flushed from their success in London, the London General Ominbus Company, which incidentally bought up most of the Underground in 1911, is selling shares in a planned national bus company.

A generation from now, Americans will be richer, more leisured, healthier and longer-lived than ever. That sentence could have been written at any time since the Mayflower landed (at least of the settlers; it was a different story for the indigenous tribes). It would always have prompted scepticism; and it would always have been true.

– Daniel Hannan begins his response to America 3.0, an optimistic book about the historic origins of and future consequences of the exceptionalness of America, by James Bennett and Michael Lotus. Hannan shares their optimism.

What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts II, III, IV, V & VI.

In modern popular culture there seem to be two distinct images of the period immediately before the First World War. The first, exemplified by Upstairs, Downstairs [I believe Downton Abbey is the modern-day equivalent] is of well-dressed people being nice to one another; and the second, one of a rigid class system with the ruling class fighting a desperate rearguard action to preserve the vast differences in wealth and privilege between them and the poorest.

Libertarians have a rather different image of the period before the First World War. They tend to think of as a Golden Age of freedom, low taxation and low regulation; an age of constant improvement, where entrepreneurs could do their thing with the minimum of interference. A time when the pound was linked to gold and people didn’t have to worry about inflation or asset bubbles; a world that was swept away by war, never to return. The question is, is this true?

One of the ways I try to answer the question is to read the Times from 100 years ago. I can do this because a company called Gale Group scanned in just about every copy there has ever been and indexed them. They then made these digitised copies available online to subscribers. I am lucky in that my local library is one of those subscribers.

When I started doing this I think the reason was partly because I thought it was a great age to be alive and partly because I wanted to see if there were things that modern historians weren’t picking up on – parts of the story that would have been familiar to people living at the time but have long since been forgotten.

Trying to make sense of the world via the pages of the Times is a little like trying to look at the world through a pinhole. Perhaps another way of looking at it would be to imagine trying to understand the modern world with the BBC as your only source of information. You’re going to miss a lot of the routine of life, a lot of the unspoken assumptions and receive a biased viewpoint into the bargain. At the time, the Times, along with the Daily Mail and (would you believe it) the Daily Mirror was part of the Northcliffe Press and as such a Conservative-supporting paper. [I say Conservative but at the time they called themselves Unionists.] The Times tends to favour trade protection and spending on the armed forces while being opposed to Irish Home Rule. It is generally sceptical of state intervention.

The Times itself is, as you would expect, very different from its modern counterpart – at least I assume so – it is a few years since I last read the print version. For starters it is very big. It is a proper broadsheet being slightly bigger than even the modern-day Daily Telegraph. It has no photographs and precious few diagrams. The front page is a bit of a shock. It is entirely filled with classified adverts. This seems a rather odd arrangement until you realise that the idea is that you open the paper in the middle where there is an index (as well as the editorials) and you work out where you want to go from there. Classified adverts remained on the front page until May 1966. The paper is usually about 24 pages long. There are no colour supplements although occasionally you will get the odd special and there is an engineering supplement every week. At this time, The Sunday Times is an entirely separate publication not becoming part of the same stable until the 1960s and is not available online.

Don’t hold the front page. The Times 4 September 1913.

There are some display adverts for many of the things you would expect: fashion, railways, buses, some cars, books and magazines. Any manufacturer of any product that you might put in your mouth: drinks, foods, compounds, medicines etc will make an outrageous claim for its disease-preventing and health-inducing abilities. For example an ad for Allinson wholemeal bread claims that:

it is a cure for constipation and its attendant evils and will do more to maintain health than all the medicines ever sold.

About the only people who don’t claim that their product will make you live forever are the tobacco manufacturers who simply claim that their product is less bad. One even sells his product on the basis that it produces less nicotine which I thought was the whole point. In the classifieds you will often find adverts for hospitals along with the rather depressing line: “Funds urgently needed.”

The writing is turgid. Writers can take an age to get to their point. And scanning doesn’t help. With a modern newspaper article you can usually extract the useful information without going to the hassle of reading the whole article. In the case of the Times from 1913 you have to read the whole bloody thing and even then you may find yourself none the wiser. I can only imagine that our ancestors had a lot of leisure time.

And they must have paid attention at school. Every so often you will find a quotation in French, Latin or Greek without translation. And, less commonly, German.

The city pages are every bit as boring as you might imagine. Much of it is given over to government debt which given the size of that market seems reasonable. There is comparatively little space given over to quoted companies largely because there are so few of them. The majority of those that do exist are in the railway, oil, rubber or tea industries. I can’t remember many of the others although the Aerated Bread Company does stick in the mind.

One curiosity is that in those days, every week, the train companies would report their receipts. The Times then faithfully reports these receipts along with those for the previous week and the equivalent week in the previous year. Incidentally, the size of the British rail network peaked in 1912.

The hardest section to read is the page and a half given over to Parliamentary proceedings. I like to think Parliament gets this much attention because this is where all the great debates of the day are taking place. And I have found the odd nugget. Samizdata readers may remember me blogging about the debate on the Lee Enfield rifle and how contemporary opinion regarded it as grossly inadequate. It went on to see service as the British Army’s principal infantry weapon in two world wars. But for the most part Parliamentary debates of 1913 are every bit as dull as they are nowadays.

A surprising amount of space is given over to sport. All the important games: cricket, racing, golf, tennis, sailing, shooting and polo are covered. Football is not entirely ignored. The Times faithfully reports the results from the league championship – a competition dominated by northern teams. The printing of league tables is a somewhat haphazard affair. At the end of the 1913 season they printed the 2nd Division table but not the First. Sunderland won in case you were wondering.

The Times also supplies match reports on the important fixtures. If you want to know what happened in the big game between Eton and Charterhouse or Harrow and Westminster there’s no better place to go.

A lot of the place names have changed since then. Üskub became Skopje, Servia: Serbia, Adrianople: Edirne, Salonika: Thessaloniki, St Petersburg is St Petersburg but for most of the last 100 years it wasn’t. Singapore is part of the Straits Settlements and there is something known as the Shanghai International Settlement.

The quick version of something the old plague-carrier said is that history repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Second time as tragedy and farce would have been more accurate.

Top comment: “I did not set a red line, Bush did it and you are a racist”

These proceedings are closed.

– General Douglas MacArthur, bringing World War II to an end as if it were a parish council meeting, sixty-eight years ago today.

Something strange just happened. Parliament has asserted itself over the Government. It doesn’t occur very often, and I can’t remember the last time the government lost a vote on a foreign policy matter. I am reminded of Viscount Cranborne‘s famous mea culpa after having been rapped over the knuckles for exceeding his authority. Like him, the executive “rushed in, like an ill-trained spaniel”, only to be chastised by the master it had almost forgotten it had.

Of course, the matter is not settled by any means. Parliament may wake up hung over and remorseful, and I’m sure the spaniel will be prowling the darkened halls of power, looking for someone to sink its teeth into, but for once it feels like we’re in a parliamentary democracy rather than an elected dictatorship.

– Richard Carey

Tomorrow evening I have another of my last Friday of the month meetings at my home in London SW1. Recent Samizdata acquisition, and a friend of mine from way back, Patrick Crozier, will be the speaker. Regular readers of Samizdata will not be surprised to learn that Patrick will be talking about what life was like in Britain one hundred years ago, this being a regular theme of his postings on this blog.

In my email to Patrick about about what I hoped he might be talking about, I wrote this:

What I have in mind is: Were They Libertarians? Any more than now? At all? Or had Germanism by then done its stuff and turned everyone into rabid statists? That kind of thing.

Patrick’s reply:

In addition to attempting to answer your question I am going to try to give a picture of what life was like: unemployment, inflation, transport etc., as well as how people viewed the prospect of war.

Which is hardly a change of subject away from the libertarianism that is the ongoing agenda of all these evenings. Opinions are opinions, but events and existing arrangements and experiences shape opinions. Unemployment, inflation, transport and war are all regular objects of libertarian contemplation. So: excellent. I look forward to it all.

I am particularly looking forward to learning more about that last bit, about how people viewed the possibility of war. Did the sort of people whose opinions were reported by or published in The Times realise what they were about to unleash, or what was about to hit them? If they did think war was coming, what sort of war did they think it would be? And did they realise what a shot in the arm the Great War would be for the power of the state?

This time next year, Patrick’s postings here about events exactly a century ago will surely get very dramatic.

If you want to be told more about this and/or subsequent Last Friday of the Month meetings, email me, by going here and clicking where it says “Contact” (top left).

Last night I attended a meeting of the End of the World Club, and by the end – of the meeting, not the world – the conversation had turned uncharacteristically optimistic. Oh, there were the usual prophecies of doom, and it is hoped that the next meeting will be someone talking about what it was like living through the Zimbabwe hyper-inflation. But the second of the two speakers last night was Rory Broomfield, speaking about the Better Off Out campaign, as in: Britain would be better off out of the European Union. That is an argument where at least some headway is now being made. How big the chances are that Britain might either leave or be kicked out of the European Union some time in the next few years, I do not know, but those chances have surely been improving. I can remember when the fantasy that “Europe” was going to cohere into one splendidly perfect union and lead the world was really quite plausible, if you were the sort already inclined to believe such things. EUrope, in those days, was a boat that Britain needed not to miss. Now, EUrope is more like a swamp into which Britain would be unwise to go on immersing itself, and should instead be concentrating on climbing or being spat out of.

Mention was made of shipping containers, i.e. of the story told in this fascinating book. Compared to the arrangements it replaced, containerisation has damn near abolished the cost of transporting stuff by sea, which means that the economic significance of mere geographical proximity has now been, if not abolished, at least radically diminished. Regional trading blocks like EUrope now look like relics from that bygone age when it would take a week to unload a ship, and when Scotch whiskey could not be profitably exported from Scotland because half of it would be stolen by dock labourers.

Containerisation also exaggerates how much business Britain does with Europe, because much of this supposed trade with EUrope is just containers being driven in lorries to and from Rotterdam, and shipped to and from the world. The huge new container port now nearing completion in the Thames Estuary is presumably about to put a demoralising (for a EUrophile) dent in these pseudo-EUropean trade numbers.

Mention was also made of a recently published map (scroll down to Number 29 of these maps). This map shows the economic centre of gravity of the world, at various times in history. A thousand years ago, this notional spot was somewhere near China. And the point strongly made by this map is that this centre of economic gravity is now moving, faster than it has moved ever before in history, from northern Europe (it was in the north Atlantic in 1950), right back to where it came from, leaving Europe behind.

Broomfield talked about how you convince people of such notions. For younger audiences, he said, just moaning on about how terrible EUrope is doesn’t do it. You have to be positive. But the trick, said Broomfield, is to be positive about the world. The important thing is that Britain, and you young guys, should not held back by EUrope from making your way in that big world.

The actual End of the World is not nigh any time soon, but the world is changing.

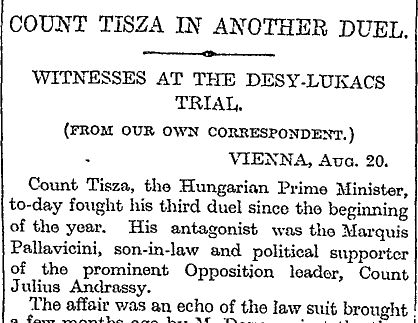

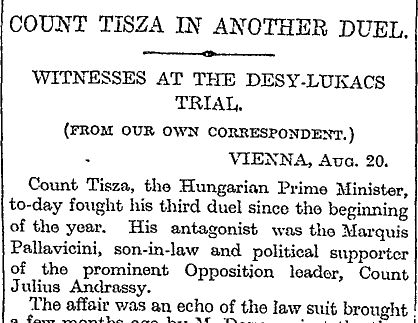

The year being 1913, of course.

The Times, 21 August 1913 p4

The whole business seems to be a bit stylised although still dangerous.

Though he was ambassador in London from 1898 to 1920, Cambon spoke not a word of English. During his meetings with Edward Grey (who spoke no French), he insisted that every utterance be translated into French, including easily recognised words such as ‘yes’. He firmly believed – like many members of the French elite – that French was the only language capable of articulating rational thought and he objected to the foundation of French schools in Britain on the eccentric grounds that French people raised in Britain tended to end up mentally retarded.

– Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers p193. While Sleepwalkers is clearly well-researched I am far from sure the research supports the conclusions i.e. that the First World War was all one big accident. I may blog more on this sometime but equally I may not.

The Times 24 July 1913 page 5

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|