The bloke who posted this describes it as,’The same scene everyone knows, except it is from a film called “Hitler: The Last Ten Days” starring Alec Guinness.’ Presumably both this film and Der Untergang followed Traudl Junge’s diaries quite closely for this scene.

|

|||||

– Geoffrey Levy, in a hit piece in the Daily Mail aimed at Ed Miliband.

– Demosthenes, in a hit piece aimed at Aeschines. [T]his Conceit of Levelling of property and Magistracy is so ridiculous and foolish an opinion, as no man of brains, reason, or ingenuity, can be imagined such a sot as to maintain such a principle, because it would, if practiced destroy not only any industry in the world, but raze the very foundation of generation, and of subsistence or being of one man by another. For as industry and valour by which the societies of mankind are maintained and preserved, who will take the pains for that which when he hath gotten is not his own, but must be equally shared in, by every lazy, simple, dronish sot? or who will fight for that, wherein he hath no other interest, but such as must be subject to the will and pleasure of another, yea of every coward and base low spirited fellow, that in his sitting still must share in common with a valiant man in all his brave and noble achievement? The ancient encouragement to men that were to defend their Country was this: that they were to hazard their persons for that which was their own, to wit, their own wives, their own children, their own Estates. And this give me leave to say, and that in truth, that those men in England, that are most branded with the name of Levellers, are of all in that Nation, most free from any design of Levelling, in the sense we have spoken of. – John Lilburne defends himself against the accusation that he was a “Leveller”. But, the name stuck. Last night Richard Carey gave a fascinating talk about the Levellers, and about the seventeenth century historical context within which the Levellers proclaimed their ideas, in the course of which he quoted the above piece of writing. Carl Watner includes it in this JLS article (p. 409) about Richard Overton. Next time I meet up with Patrick Crozier, I will be giving him a present. I hope that the next time we meet will be if he drops by at my place tomorrow evening. Then, Richard Carey will be giving a talk about “The English Radicals: 1640-1660”, but I believe that work commitments may prevent Patrick from being at that. Richard Carey will be talking about:

As always with these talks, I expect to learn a lot. To find out more about them, click where it says “Contact” here. The present for Patrick Crozier is this: That’s twenty one ancient copies of The Times. I saw a great stash of these in a local charity shop, and, knowing Patrick’s interest in the past of this newspaper, especially when world wars are involved, I purchased one, dated May 24th 1940. I asked Patrick if he’d like this copy, and more. He expressed enthusiasm. So, yesterday I went back and bought all the rest. Originally these copies were sold for 2d. These same copies each cost me exactly as much as a copy of The Times would now cost, £1. Someone else had also had a go at the pile by then, but there were plenty left. The dates of the copies I now have are: 1939 – October 2; November 18, 20, 22, 24, 25, 27, 29; December 5, 13, 15, 19 Giving gifts to one’s friends these days is hard. Stuff worth having tends not to cost nearly as much as it used to. If a friend wants, say, some spoons, he just buys some spoons, of exactly the sort he wants. Why give him other spoons of the wrong sort? Besides which, the gift most of us would really like would not be more crap, but more space to accommodate all the crap we already have. So, when the chance occurs to give a friend a gift that they really might like, costing about the right amount in money or bother, it makes sense to grab that chance. LATER: I’ve just discovered that what I thought was December 27th 1939 was actually September 27th 1938. Before WW2 began, in other words, which will please Patrick. There’s a big Hitler speech about Czechoslovakia. I was reading an article about the creation of the Federal Reserve Bank (boo, hiss) in 1913 and I came across this:

Cue utter confusion. For starters, why would a bank want to issue currency? Surely, a bank has all the money it wishes to lend out in the form of deposits. And what is meant here by currency? notes and coins or money in general?

This is really confusing. I can understand how notes work in a goldsmith system. Briefly, a depositor deposits some gold with the goldsmith and in return receives a receipt for that gold. The receipt, or note, is then capable of being used as money because it is literally “as good as gold”. I can see how government bonds might replace gold but it requires a depositor. And surely, once a depositor has deposited his bond the bank can issue its own receipts/notes rather than having anything to do with the government. Or maybe that’s illegal. Or maybe depositors would prefer to use government notes as they are accepted in more places. “…a normal and elastic currency system”. What do they mean by “elastic”? Do they mean what modern-day Austrian economists mean i.e. inflationary? I doubt it because at the time the UK was on a gold standard which tends to be anti-inflationary [notwithstanding comments I have made about how there was some inflation at the time]. And what’s all this about commercial paper? The modern meaning is short-term business debt. I can kind of see how that would replace government bonds although presumably it would have to be extremely homogenous and what happens when the term is up? And where, if anywhere, is the link with gold which, as I understand it, was one of the main issues in the 1896 presidential election? Whatever the case may be it seems clear that the US monetary system was far from being a free market before the Fed came along. One last thought: there are times when I think the confusion that monetary matters generate is deliberate rather than accidental. What follows is the final part of a series based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, II, III, IV. & V When reading about the time it is impossible to be unaware that in less than a year Europe will be plunged into war. It is not as if they are unaware of the risk. Churchill, hardly a pacifist, describes the prospect as “Armageddon”. A recent series of articles have appeared in the Times under the title “Europe’s Armed Camp”. In the 1900s, Germany began to build up its navy. Britain responded. By 1913 Germany is ready to throw in the towel. Britain has not only shown herself prepared to outbuild Germany at every step but has raised a Territorial Army to fend off a potential invasion. She has also developed plans to send an Expeditionary Force to the Continent should the need arise. Meanwhile and simultaneously, France and Germany have both expanded their armies. It is worth spending a little bit of time describing the political systems in Central and Eastern Europe. Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia all had systems that were partly monarchical and partly parliamentary. In Germany the Kaiser made all the appointments. The Reichstag was elected on a wider franchise than the House of Commons i.e. universal male franchise and it had the power to block the Kaiser’s bills including the budget. Austria-Hungary had parliaments everywhere although the Hungarian was elected on an extremely restricted franchise and there were some magnificently complicated arrangements for making decisions, such as military spending that affected the whole empire. In the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution, a parliament, the Duma, was elected on a universal male franchise. It had rather too many socialists for the Tsar’s liking so the franchise was narrowed until he got something more acceptable. The Duma is not entirely powerless but does not appear to have any control over the budget. The 1905 Revolution took place in the wake of Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. This severly weakened Russia both on land and on sea. She has been rebuilding her forces but it is a slow process. In the absence of a strong Russia, Austria has been having a field day in the Balkans. It annexed Bosnia in 1908, created Albania to prevent Serbian access to the Adriatic and has detached Bulgaria from her alliance with Russia. And yet Austria is worried. Historians of the period love telling us how many times Conrad von Hötzendorf, Chief of the Austrian General Staff, urged war on Serbia. The number is well into the twenties. The Serbs make no secret of their desire to add the Austrian territories of Bosnia, Croatia and Slovenia to their own. The Austrians see this has highly destabilising: should Croatia go why not Bohemia, or Slovakia, or Ruthenia? There are some extraordinarily disturbing ideas knocking around Germany. In his book “The Next War” General Bernhardi talks about the need to smash France, curb Britain and ignore treaties and other promises into the bargain. The Prime Minister, Bethmann-Hollweg, the “Good German”, talks of a coming race war between Teuton and Slav. In addition to threats abroad they face threats at home. The Socialists are the largest party in the Reichstag and it is becoming ever more difficult to get their army and navy bills enacted. What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, II, III, IV & VI. In 1913, Britain has an empire. A very big empire. It’s pretty peaceful, doesn’t appear to be very expensive and doesn’t appear to be very controversial. The problem is that the British have no idea what to do with it. It is, let’s face it a pretty disparate and far flung bunch of territories. About the only thing that connects them is that Britain got to them before anyone else. In 1906, the Unionists went into the general election proposing an Empire-wide common external tariff otherwise known as Imperial Preference. Given that this would have put up the price of food and given that that’s what about 50% of average incomes were spent on it is not surprising that the Liberals won by a landslide. What is surprising is that the Unionists refuse to ditch it. There are proposals to build a Channel Tunnel. Given that it didn’t get built until 80 years later, using much better technology and at great cost, you would have thought the main concern would have been over its feasibility. But no. The main concern, or at least the one occupying the minds of the Times and its correspondents, is how an invader might use it. Could an invader take both ends? Could it be blown up? What if they put the entrance on a viaduct and blew that up? Those are the sort of questions being asked. Some controversies and concerns will seem odd to us. A lot of space is given over to agriculture, Welsh disestablishment and the teaching of Greek. One of the big hullabaloos is over the Olympics. Britain did not do very well in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics only coming third in the medal table. This has caused a great deal of wailing and gnashing of teeth not least from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who feels that Britain risks losing her reputation as the “Mother of Sport”. He believes there are only three options for dealing with this catastrophe: accept the humiliation, withdraw from the Olympics entirely or create a subscription-based fund to pay for the recruitment and training of future Olympic champions. Cue letters to the Times arguing that we should withdraw as quickly as possible as the Olympics already represent a ridiculous perversion of the amateur principle. At no point has anyone suggested that they should be using taxpayers’ money. What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, II, III, V & VI. Drugs. When I was preparing this piece I was under the illusion that drugs were legal. That’s not quite the case. Since as long ago as 1868, only pharmacists could sell opium. In 1908 cocaine was put onto a similar footing. As far as I am aware there are no restrictions on cannabis. At the 1912 International Opium Convention most European states agreed to end the trade although Germany, Austria and Turkey dissented. The Convention was eventually incorporated into the Versailles Treaty. When I started delving into the pages of the Times my assumption was that there was very little regulation. The more I read the more I realise this isn’t really true. Every train crash prompts a government-led investigation. Companies must submit returns on how many accidents there have been on their premises. Back-to-back housing has been banned. In 2000, the Telegraph reprinted and edition from 1 January 1900. Sure enough, there was a little article reminding readers that a regulation had come into force on the availability of stools for female shop workers. Having said that a few years ago I was reading up on the Regulation of the Railways Act from the 1880s. This made various demands on companies but it turned out that most companies had put these measures into place well before the law was even thought of. In other words regulation was following existing practice. It would be interesting to know if this was still a common feature in the 1910s. In an editorial in part on the topic of drug regulation the Times of March 18 1913 had this to say. Some of the sentiments may seem familiar:

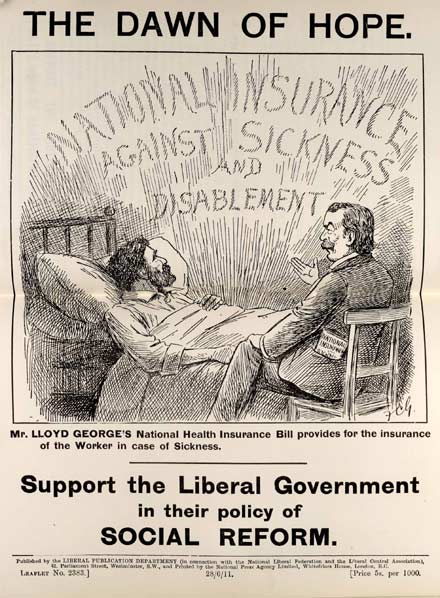

Mind you they’re not always banning things. In 1910, an explosion at the Pretoria Pit near Bolton killed over 300 miners. While there was a great deal of sympathy expressed there was very little suggestion that this was a problem to which the solution was more state regulation. There is an organisation called the Liberty and Property Defence League – incidentally, based just around the corner from the current-day Adam Smith Institute – which occasionally gets letters into the papers and another called the Cobden Club which mainly aims at preserving peace. It is legal to own a gun so long as you have a licence to do so. The licences themselves cost 10 shillings. And guns get used. Ex-lovers, ex-wives, scab labourers and people hanging around having a quiet drink in a hotel bar have all become victims of 1910s gun crime. In another incident, an actor managed to get himself killed while on stage when a fellow actor, as part of the play, fired on him with blanks. Incidents like this would be shocking today and yet the murder rate was about half what it is now. In December 1910, the police were called to a burglary in progress in Houndsditch. The burglars opened fire killing three policemen and sparking a manhunt. In what became known as the Siege of Sidney Street some of the perpetrators, believed to be East European anarchists, were tracked down. The army were called in and in an exchange of fire a bullet narrowly missed the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill.  What, exactly, the policemen think they are going to achieve with those shotguns is anyone’s guess. From here. He’s not the only person to have had shots aimed at him. Edward Henry, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, was shot by a man he’d turned down for a taxi licence. Leopold de Rothschild had shots fired at him. But the real fun is abroad. In the years leading up to the First World War, the King of Serbia, the King of Greece, the Russian Prime Minister, the Grand Vizier of Turkey, a French President, an American President and (famously) the heir presumptive to the Austrian throne will all be assassinated. On the eve of the First World War the wife of an ex-French Prime Minister will be on trial for the shooting of a newspaper editor. In the years following the 1905 Russian Revolution something like 2000 Tsarist officials were assassinated. Mind you, the great and the good were just as susceptible to natural causes. In the years leading up to the First World War a US ambassador to London, a German Foreign Minister and an Austrian Foreign Minister will all die in office. The Russian ambassador to Serbia will die during the July Crisis and a British general, Grierson, will die on his way to the front. A Fortnum’s hamper was found by his side. Court cases of all kinds tend to be over quickly and juries usually make up their minds within the hour. I suspect the fact that they aren’t paid for their time plays a large part in this. Punishments include hanging and flogging. Flogging takes two forms: the cat if they’re up to it and the birch if they are not. One thing that still surprises me is access to these courts. Ordinary people, for instance, can and do bring libel cases. Homosexuality is illegal but it appears to be rarely prosecuted. The word “homosexual” appears once in ten years and that is in relation to a libel case in Germany. I recently read about a blackmail case. A mother accused a merchant of “ruining” her son. I assume this is a euphemism for buggery. The merchant paid her £150 which in those days would buy you 40 ounces of gold – about £35,000 at today’s prices. A few months later the mother made further demands at which point the merchant went to the police and the mother and son were prosecuted for blackmail. At no point is there any question of the merchant being prosecuted for a criminal offence despite the fact that by his actions he’s effectively admitted to it. Could it be, that so long as you were discreet the state wasn’t that bothered? What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, II, IV, V & VI. Politically, these are radical times. In 1906 a Liberal government was returned by a landslide. Elections in those days were very different from the way they are today. For starters, the electorate was much smaller. Women couldn’t vote at all and men had to be over 21 and pass a not particularly onerous property qualification. General elections themselves, took place over the course of a couple of weeks. In each constituency the voting would take place over a number of days and it would not be the same days in each constituency. As a consequence the results would filter in over the course of a week. Up until 1910, MPs weren’t paid at all. If they wanted to become a minister they would have to resign their seat and fight a by-election. The Liberal government introduced the Workmen’s Compensation Act, old-age pensions, sick pay, unemployment benefit for certain trades, maternity benefit, nationalised GPs, allowed Trade Unions to pay strike pay and, as I mentioned earlier, nationalised the telephones. To pay for it all they upped taxes. At this point the Unionist-dominated House of Lords objected causing a constitutional crisis. After two general elections in 1910 and a threat to create 1000 new peers the Lords’ backed down and their power to block money bills was removed for good. Sick pay is not working particularly well. In the days when sick pay was entirely in the hands of friendly societies they had powerful incentives to make sure that people claiming sick pay were indeed sick as indeed did the doctors in their pay. Now that the state bears the costs you will be shocked to hear that there has been a dramatic increase in the number of people claiming sickness benefit. Malingerers, as they are known can get away with it because doctors are signing them off as sick without making a proper examination. In 1910 the Liberals lost their majority and went into coalition with Labour and the Irish Nationalists (one of whom, incidentally, represents a constituency in Liverpool). The price of Nationalist support is Home Rule and the obstacle to that, as always, is Ulster. In the North, men are drilling and guns are being run. The Unionists are in the process of setting up a provisional government. The penny is beginning to drop that this could end in Civil War. The suffragettes are causing chaos. They are breaking windows, destroying mail, disrupting political meetings, and burning down country houses. When jailed they go on hunger strike. Initially, the state force fed them. When this proved unpopular it started releasing them when they became weak and re-imprisoning them when they’d become stronger. Known as the Cat and Mouse Act it simply proves that the state has no idea what to do. It could of course give women the vote. A bill was introduced in May 1913 but mysteriously failed to pass. While arguing against it, the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith amid much tedious inconsequential waffle argued that the bill would enlarge the franchise both too much and too little and therefore, it should be rejected. What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts I, III, IV, V & VI. Little is said about the economy – not that that was a term in common use at the time. Unemployment – known as idleness – seems non-existent but there is some inflation – referred to as an “advance in prices” or “an increase in living costs”. Seeing as the pound was tied to gold at a rate of about £4 per troy ounce this seems surprising although the enormous gold finds in South Africa may have had something to do with it. Inflation may have been the cause of the many strikes at the time and it may have been the effect. The tax take is about 10%. Today it is over 40%. Northerners are better off than Southerners. In 1912 the Titanic, the largest moving object in the world, set sail on its maiden voyage. Most people are aware that it sank, which is notable enough. But the really amazing part is that it got out of port at all. There had been a month-long national coal strike immediately beforehand and supplies were extremely low. Strikes are extremely common. In addition to the national coal strike, recent years have seen a national rail strike, a London dock strike and a Hull dock strike. London is currently undergoing a painters and decorators’ strike and Dublin a tramworkers’ strike. In a previous coal strike, in 1910 in South Wales, troops had been used to put down a riot. At about the same time troops were also used to put down a riot in Liverpool. The state is starting to nationalise things. In 1911 it nationalised the National Telephone Company. I should explain that this isn’t quite as dramatic as it sounds. The state already owned the trunk lines. The National Telephone Company owned everything else and operated them under licence. In 1911 the licence simply wasn’t renewed. In London, the County Council, late in the day, built an electric tram network. It was completed just in time for motor buses to take their market away from them. It is difficult to detect any class, race or sex prejudice in the pages of the Times. In 1913, the world is undergoing a transportational revolution. The horse is being swept from the streets of London to be replaced by electric trams, motor buses, motor lorries and motor cars. Below the streets, the deep-level, electrified tube lines are being built while steam trains are being replaced by electric ones on the older cut and cover lines. We are seeing the beginnings of surburban electrification. Buses, in particular, are allowing people to travel much further to work and to shop. The only downside is that a lot of people are getting killed on the road. Talking of buses, this is still a time when entrepreneurs are able to think big. Flushed from their success in London, the London General Ominbus Company, which incidentally bought up most of the Underground in 1911, is selling shares in a planned national bus company. A generation from now, Americans will be richer, more leisured, healthier and longer-lived than ever. That sentence could have been written at any time since the Mayflower landed (at least of the settlers; it was a different story for the indigenous tribes). It would always have prompted scepticism; and it would always have been true. – Daniel Hannan begins his response to America 3.0, an optimistic book about the historic origins of and future consequences of the exceptionalness of America, by James Bennett and Michael Lotus. Hannan shares their optimism. What follows is based on a talk I gave at the end of August at one of Brian’s Fridays. See also Parts II, III, IV, V & VI. In modern popular culture there seem to be two distinct images of the period immediately before the First World War. The first, exemplified by Upstairs, Downstairs [I believe Downton Abbey is the modern-day equivalent] is of well-dressed people being nice to one another; and the second, one of a rigid class system with the ruling class fighting a desperate rearguard action to preserve the vast differences in wealth and privilege between them and the poorest. Libertarians have a rather different image of the period before the First World War. They tend to think of as a Golden Age of freedom, low taxation and low regulation; an age of constant improvement, where entrepreneurs could do their thing with the minimum of interference. A time when the pound was linked to gold and people didn’t have to worry about inflation or asset bubbles; a world that was swept away by war, never to return. The question is, is this true? One of the ways I try to answer the question is to read the Times from 100 years ago. I can do this because a company called Gale Group scanned in just about every copy there has ever been and indexed them. They then made these digitised copies available online to subscribers. I am lucky in that my local library is one of those subscribers. When I started doing this I think the reason was partly because I thought it was a great age to be alive and partly because I wanted to see if there were things that modern historians weren’t picking up on – parts of the story that would have been familiar to people living at the time but have long since been forgotten. Trying to make sense of the world via the pages of the Times is a little like trying to look at the world through a pinhole. Perhaps another way of looking at it would be to imagine trying to understand the modern world with the BBC as your only source of information. You’re going to miss a lot of the routine of life, a lot of the unspoken assumptions and receive a biased viewpoint into the bargain. At the time, the Times, along with the Daily Mail and (would you believe it) the Daily Mirror was part of the Northcliffe Press and as such a Conservative-supporting paper. [I say Conservative but at the time they called themselves Unionists.] The Times tends to favour trade protection and spending on the armed forces while being opposed to Irish Home Rule. It is generally sceptical of state intervention. The Times itself is, as you would expect, very different from its modern counterpart – at least I assume so – it is a few years since I last read the print version. For starters it is very big. It is a proper broadsheet being slightly bigger than even the modern-day Daily Telegraph. It has no photographs and precious few diagrams. The front page is a bit of a shock. It is entirely filled with classified adverts. This seems a rather odd arrangement until you realise that the idea is that you open the paper in the middle where there is an index (as well as the editorials) and you work out where you want to go from there. Classified adverts remained on the front page until May 1966. The paper is usually about 24 pages long. There are no colour supplements although occasionally you will get the odd special and there is an engineering supplement every week. At this time, The Sunday Times is an entirely separate publication not becoming part of the same stable until the 1960s and is not available online. There are some display adverts for many of the things you would expect: fashion, railways, buses, some cars, books and magazines. Any manufacturer of any product that you might put in your mouth: drinks, foods, compounds, medicines etc will make an outrageous claim for its disease-preventing and health-inducing abilities. For example an ad for Allinson wholemeal bread claims that: it is a cure for constipation and its attendant evils and will do more to maintain health than all the medicines ever sold. About the only people who don’t claim that their product will make you live forever are the tobacco manufacturers who simply claim that their product is less bad. One even sells his product on the basis that it produces less nicotine which I thought was the whole point. In the classifieds you will often find adverts for hospitals along with the rather depressing line: “Funds urgently needed.” The writing is turgid. Writers can take an age to get to their point. And scanning doesn’t help. With a modern newspaper article you can usually extract the useful information without going to the hassle of reading the whole article. In the case of the Times from 1913 you have to read the whole bloody thing and even then you may find yourself none the wiser. I can only imagine that our ancestors had a lot of leisure time. And they must have paid attention at school. Every so often you will find a quotation in French, Latin or Greek without translation. And, less commonly, German. The city pages are every bit as boring as you might imagine. Much of it is given over to government debt which given the size of that market seems reasonable. There is comparatively little space given over to quoted companies largely because there are so few of them. The majority of those that do exist are in the railway, oil, rubber or tea industries. I can’t remember many of the others although the Aerated Bread Company does stick in the mind. One curiosity is that in those days, every week, the train companies would report their receipts. The Times then faithfully reports these receipts along with those for the previous week and the equivalent week in the previous year. Incidentally, the size of the British rail network peaked in 1912. The hardest section to read is the page and a half given over to Parliamentary proceedings. I like to think Parliament gets this much attention because this is where all the great debates of the day are taking place. And I have found the odd nugget. Samizdata readers may remember me blogging about the debate on the Lee Enfield rifle and how contemporary opinion regarded it as grossly inadequate. It went on to see service as the British Army’s principal infantry weapon in two world wars. But for the most part Parliamentary debates of 1913 are every bit as dull as they are nowadays. A surprising amount of space is given over to sport. All the important games: cricket, racing, golf, tennis, sailing, shooting and polo are covered. Football is not entirely ignored. The Times faithfully reports the results from the league championship – a competition dominated by northern teams. The printing of league tables is a somewhat haphazard affair. At the end of the 1913 season they printed the 2nd Division table but not the First. Sunderland won in case you were wondering. The Times also supplies match reports on the important fixtures. If you want to know what happened in the big game between Eton and Charterhouse or Harrow and Westminster there’s no better place to go. A lot of the place names have changed since then. Üskub became Skopje, Servia: Serbia, Adrianople: Edirne, Salonika: Thessaloniki, St Petersburg is St Petersburg but for most of the last 100 years it wasn’t. Singapore is part of the Straits Settlements and there is something known as the Shanghai International Settlement. |

|||||

All content on this website (including text, photographs, audio files, and any other original works), unless otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons License. |

|||||