We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

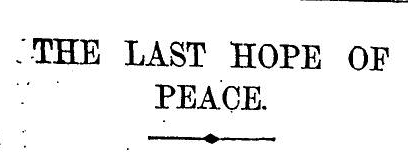

The “July Crisis” of 1914 may have come as a shock to the British but that does mean they were not able to weigh their options. I was surprised by the excellence of a couple of articles I came across in The Times. One of them appeared on the editorial pages, did not have a byline but didn’t appear to be an editorial either. It was still good though. This is the key passage:

France does not threaten our security. A German victory over France would threaten it irremediably. Even should the German Navy remain inactive, the occupation of Belgium and Northern France by German troops would strike a crushing blow at British security. We should then be obliged, alone and without allies, to bear the burden of keeping up a Fleet superior to that of Germany and of an Army proportionately strong. This burden would be ruinous.

That is the best explanation from Britain’s decision to go to war I ever heard. Peace is perilous.

The other was a letter from Norman Angell, author of The Great Illusion:

We are told that if we allow Germany to become victorious she would be so powerful as to threaten our existence by the occupation of Belgium, Holland, and possibly the North of France. But, as your article of to-day’s date so well points out, it was the difficulty which Germany found in Alsace-Lorraine which prevented her from acting against us in the South African War. If one province, so largely German in its origin and history, could create this embarrassment, what trouble will not Germany pile up for herself is she should attempt the absorption of a Belgium, a Holland, and a Normandy?

Rather depends on how civilised she plans on being. He goes on:

The object and effect of our entering into this war would be to ensure the victory of Russia and her Slavonic allies. Will a dominant Slavonic federation of, say, 200,000,000 autocratically governed people, with a very rudimentary civilisation, but heavily equipped for military aggression, be a less dangerous factor in Europe than a dominant Germany of 65,000,000 highly civilised and mainly given to the arts of trade and commerce?

A prediction, of course, that manages to be both very wrong and, ultimately, very right.

It will be obvious that this post was prompted by Perry Metzger’s post “A Sad Anniversary”.

Regarding the undoubted fact that the net result of the First World War was almost wholly bad, consider this analogy: your home is invaded by a gang, who have given ample evidence of their lawless nature as they rampaged through your neighbourhood before reaching you. Maybe you have not always been a blameless citizen yourself, but, by God, you won’t take this lying down. So you resist, calling in your family and neighbours to help. They pay a high price for their solidarity. At the end of the fight you look round and see relatives and friends dead, crippled and embittered. The neighbourhood you sought to defend has been wrecked. You also know that many of those dead gang members were more deluded than evil. What was it all for? Nothing has been gained, much has been lost. Worse yet, this slaughter will begin a cycle of violence that will take many more lives in future. Surely it would have been better all round to just let them in and let them take what they want?

Or would it?

One hundred years ago today, on July 28th, 1914, a month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on the Kingdom of Serbia and began an invasion. This was the official beginning of World War I.

Within weeks, every major and most minor countries in Europe had declared war upon some subset of the others.

Almost all wars are a terrible, stupid waste of human life, but “The Great War” was especially pointless.

You can grossly oversimplify and explain what most wars were about in a sentence or two. World War II could be said to have been about a group of governments attempting to gain through conquest and others trying to stop them. Vietnam could be explained as the US government’s attempt to back an authoritarian government with little internal support to try to hold back a communist takeover. These aren’t great explanations but they’re at least “sort of” explanations.

World War I has no real explanation beyond “a bunch of inter-governmental alliances got triggered in the aftermath of an assassination.” If you study the events in a history class, it takes days to explain the causes of the war, which is to say, to get to the point where you understand that there wasn’t really much of a cause, and not really much in the way of actual objectives on either side. (Sure there are “explanations” and I’m certain someone with a pedantic streak will bring them up, but I feel that they’re beside the point.)

It was not war for conquest, not war for political objectives, just war for war’s sake.

In spite of this lack of real purpose, enormous patriotic fervor was brought to bear by both sides. Anyone opposing the war was painted as a near enemy of humanity. Young men by the millions were conscripted or (even more tragically) convinced to voluntarily enlist “for their country”.

In the end, 16 million people died and a further 21 million suffered injury, some grievously enough to render them crippled for life, and all, in the end, to accomplish nothing of significance.

One might have thought that something might have been learned by our culture from this event, that the deaths of the millions might have at least brought about some sort of lasting moral disgust that convinced people that perhaps there was something deeply sick about blind patriotism, that perhaps warfare was in general not a glorious pursuit, that perhaps the presumption that governments act in the interest of their population might be misguided, etc.

There was, of course, a brief paroxysm of loathing. How could there not be when so many of Europe’s young men died uselessly in muddy holes? However, it did not last. The cultural memory faded quickly. Eventually, the world went back to business as usual, with governments slaughtering each other’s populations, and even more often their own populations, with increasing zeal.

World War I proved to be just an overture. The 16 million killed were barely a footnote in what was to come. In the 20th Century, about 160 million people died in wars, and about a further 260 million were killed by their own governments in democides of one sort or another. That’s 420 million people killed by various sorts of government managed madness in a single century alone.

420 million people killed by governments. That’s a staggering figure, far, far beyond my ability to comprehend.

Has the bloodletting ceased, now, in the 21st century? No, of course it has not. The human race appears to be immune to education.

And this is why, tonight night, I’m going to sit in a very old pub in New York City, raise a glass of scotch, and mourn for the dead, as too few people seems to remember them.

Today is the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. It is easy – way too easy, in fact – for a Brit to make some sort of snide comment about the bloody awfulness (literally) of the events of that time, the Revolution, the terrible example of, well, the Terror, and so on. But, but trying to rise above all that obvious “god those Frenchies made a right pig of their revolution” sort of line, I am going to ask readers the following: What were, in your view, the good things that flowed from the Revolution?

Go on.

Instapundit linked to this: Razr Burn: My Month with 2004’s Most Exciting Phone. Apparently, having become accustomed to smartphones, the lady found the ten year old Motorola Razr V3 un-smart.

Lady, that ain’t a 2004 phone.

This is a 2004 phone.

OK, it would have been nice at this point to download a picture of my phone. But one can’t do that with the Sagem myX-2, the only cell phone that a person of discernment need ever own. The myX-2 does not hamper my appreciation of the world by tempting me to take photographs. Nor does it download things, preferring to keep itself pure. I believe that it is capable of going to look at the internet, at warp 48.3, I am told, but in the decade since I first owned this jewel among telephonic devices, my affairs have never been so disarranged as to oblige me to attempt this feat.

It sends text messages. There is a thing called “predictive text”, but I prefer to make my own decisions.

It has a picture puzzle in which one does something or other with a grid of numbers. Of course technology has moved on and no one nowadays would play anything so primitive.

It falls into rivers. It gets left in the saddlebag of a bicycle stored in a lean-to shed for a month. It is stroked lovingly by people who had one in 2003. It distracts jurors from the case in hand when all the mobiles have to be put in a safe and it is the coolest one there. It bounces. It will be replaced when it finally dies which is sure to happen by 2008 at the latest.

You can telephone people on it.

Samizdata’s World War 1 correspondent Patrick Crozier and I are presently in Sarajevo, on the hundredth anniversary of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which triggered World War 1. It has been a slightly peculiar occasion, as nobody – local, or visiting – seems to be quite clear about what exactly is the correct way to commemorate such an event. There are musical events, art exhibitions (mostly only tangentially related to the occasion), conferences, and a vast number of television crews from all around the world looking for people to interview and things to film other than one another, mostly without great success. It has been, a long, hot day, and the journey into Sarajevo from Belgrade (that we made yesterday evening) is a long and tiring one through steep mountain roads, and I lack the strength to write at length now, alas.

However, whatever the correct way of commemorating an event such as this is, my guess is that it does not involve dressing up as the Archduke and/or his wife Sophie and sitting in a similar open car to the one they were riding in when they were murdered on the exact same spot exactly one hundred years earlier.

It was, however, possible to to that in Sarajevo today.

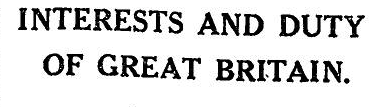

The Times 20 June 1914 p8 Now you might think that a headline like that (from 20 June 1914) would be prescient. But no. They are not referring to the prospect of a world war but to the prospect of civil war in Ireland.

It is an issue that has been dominating the pages of The Times for the last two years. In that time the debate had not moved on an inch. It can’t because the aims of nationalists and unionists are fundamentally incompatible.

For our ancestors the prospect of a world war exists but there are no obvious crises at the moment and anyway all those that have threatened to blow up have been diffused pretty quickly.

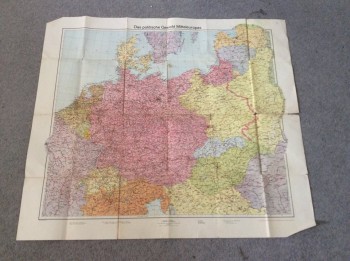

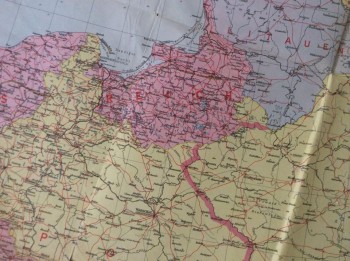

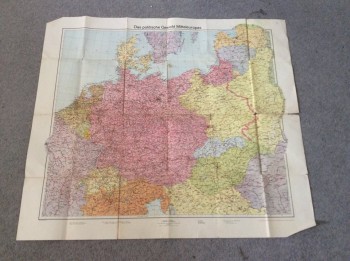

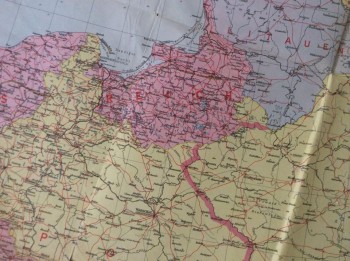

Partly due to despair at my unwillingness to decorate my flat in any way whatsoever, and partly because she knows I like this kind of thing, a friend of mine sent me this antique map of central Europe as a gift. She obtained it in an antiquarian map shop in Krakow, Poland.

First, obvious observation. This is a map from Nazi Germany. In the margin, it is identified as being the product of a mapmaker in Leipzig, but there is no date given.

Secondly, when I see a historical map, I like to play the game of figuring out the dates of the map by looking at the border, and using my historical knowledge of political geography to narrow the date down.

Figuring out the year of this map is easy. This map is from 1939. In most instances, getting the year is all you want to do. However, 1939 was a somewhat problematic year.

Klaipeda and the area around it is shown as part of Germany, not Lithuania. Also, Czechoslovakia has ceased to exist, Bohemia and Moravia has been annexed by the Reich, Slovakia is a supposedly independent country, and Carpathian Ruthenia has been invaded and annexed by Hungary. All these events occurred in March 1939, so the map was clearly designed after March 1939.

It’s looking at Poland that things get interesting. Firstly, Danzig is not shown as a free city, but is shown as part of the Reich. Danzig was invaded by Germany on 1 September 1939, proclaimed part of Germany on 2 September, and formally annexed under German law on 8 October. Danzig had, however, been under the control of the local Nazi party since 1933, and would have joined Germany instantly if it had been allowed to under international law. Is it possible that some German maps showed Danzig as part of Germany prior to September 1939? Possible, but I suspect probably not.

By far the most fascinating thing in this map is the red line through Poland, however. Poland is clearly identified as “Polen”, but the Molotov-Rippentrop line – it the limits of German occupation after the invasion of Germany in September 1939 – has been drawn through it. Therefore the map must have been printed no earlier than September 1939. This has clearly been printed at the same time as the rest of the map – it is not something someone added with a pen later, or anything like that.

What I suppose is possible is that the mapmaker had a map prepared reflecting recent border changes immediately prior to the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. When the invasion occurred, the map was quickly modified to show Danzig as German and the zones of German and Soviet occupation before being printed and sold.

And yet, this map does not reflect the view of the world that the Nazis wanted to present. Upon invading Poland, they declared that Poland as a country did not exist. On that same date of October 8, Germany formally annexed the northern and western sections of their Polish conquests (including the Suwalki triangle, clearly shown on this map), and declared the South-East to be the “General-government”, essentially a German colony (but not a “Germany colony in Poland”, as Poland did not exist). This map is therefore curious, as it essentially shows Poland (clearly identified as Poland) under German (and Soviet) occupation.

I cannot imagine maps like this being printed in Germany long after the annexation decree of October 1939. In the Nazi view, there was no occupied Poland the way there was later an occupied France. There was simply German territory that unfortunately happened to have Poles, other Slavs, and Jews living in it. It’s easy to imagine foreign maps from later showing the German and Soviet occupation of Poland like this, but German ones, not so much. So my conclusion is that this map was printed very soon indeed after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939.

Plus of course this map ended up in an antiquarian map shop in Krakow in Poland, which between 1939 and 1945 was in that aforementioned “General Government”. One has no idea how and when it got there, but I suspect that “during the occupation” is the most likely answer.

Thoughts anyone?

It is rather hard to believe that an entire decade has rolled on since the first private manned vehicle released the surly bonds of Earth and flew into space, a realm where heretofore only governments had trod. It was the beginning of a new age, and much has come to pass since then. As with all prognostications, my thoughts of the time were both more and less than the reality of 2014 in commercial space.

I would certainly have been surprised by two things, one of which I would have predicted and one of which I did not even imagine. I am sure at the time I would with certainty have said someone would be flying passengers by now. I would have been equally surprised had someone told me I would be a member of the XCOR Aerospace team working on the Lynx space plane with my own desk in the same location from which I filed my stories that day, in the same room which I had pitched my air bed the night before the big event. I would likewise have been happily surprised to find George Whitesides, our then new Executive Director at the National Space Society, who appears in some of my photos that day, would now be CEO of Virgin Galactic.

So what has happened in the ensuing ten years? For one, SpaceX is now making deliveries to the International Space Station on a regular basis with its Dragon Cargo ship, lifted via its Falcon 9 rocket. They are now sucking up the launch vehicle market, once a near American preserve, that Old Space and their political cronies proved incapable of holding. Noone, not even the Chinese or the French can compete with SpaceX’s prices. Why? No one ever before built a launch vehicle from the ground up to be viable without government cost plus contracts to foot the bill. SpaceX did take government contracts, but they worked through fixed price commercial style contracting. Their startup capital was private venture money that came from the pockets of Elon Musk and friends of his. He put every cent he had on the line and very nearly lost it. He made it through the early Falcon 1 test failures (which I live blogged here as well) on a wing and a prayer. Those failures were pretty much an inevitable part of learning to do something hard in a different way. Elon stuck his own tuckus way out over the edge… and he won.

Virgin Galactic, the company that will be flying SpaceShipTwo, the follow on to the vehicle launched that day ten years ago, has had its share of difficulties, but the company is well funded and they are plodding along towards the finish line for a suborbital tourist vehicle. XCOR is doing pretty much the same, although with a more ‘right stuff’ flight experience.

SpaceX unveiled its Dragon II capsule a couple weeks ago. They will carry out escape system testing this year and will likely be in manned test flight next year. By 2016-17 they will be a Spaceline that is delivering passengers to the International Space Station and the soon to be launched Bigelow Aerospace space station. Robert Bigelow has been ready for years now… but it did not make business sense to create a destination in space until someone could provide a regular taxi service. When the manned Dragon goes operational, I expect his extensively space tested module technology (two ‘small’ ones are currently in orbit) will go up very soon thereafter.

SpaceX has also been working towards a re-usable first stage. They have succeeded in a liftoff, flight to 1000 meters and a precise landing of a Falcon 9R first stage on the spot in Texas from which it lifted. They recently returned one of those stages from a for-hire launch and brought it to a hover over the North Atlantic waves. Later this year they will fly one from a pad at Spaceport America in New Mexico, perhaps as high as 100,000 feet, and then bring it to a landing. Next year they plan to bring one back from a commercial flight to a dry land site. It will then be checked out for re-usability and possibly reflown. They expect ten flights per stage but even if they only got two, it would halve the capital cost of a launch. If they get the full ten, we are looking at a total collapse of Old Space, a Reardon Steel moment. The only survivors will be those few protected by the Wesley Mouch’s of the world.

Later this year, SpaceX will be launching the first Falcon 9 Heavy. It will have the largest cargo capacity available on Earth and that has only ever been outdone by one vehicle, the US Saturn V Moon rocket. One might make a case to put the Space Shuttle and the short lived Buran in that exalted class, but their actual payload to orbit was mostly vehicle weight.

So much is happening in the New Space sector in June 2014 or is scheduled over the next one to two years that I would need to write a far longer article than this to come close to a proper treatment of the topic. I have not even mentioned most of the companies in our industry. Sadly there is also much I cannot talk about as I am drawing my wages in the field and that places limitations on me. If you want more details on XCOR… you can go read the company blog which can be found via the XCOR home page.

And now… a trip down memory lane. Rand Simberg just wrote his retrospective and since he and I were traveling together for that momentous day, here are the stories I filed as well, plus one other by Johnathan Pearce. The pictorial is at the end. There are a lot of fond memories there!

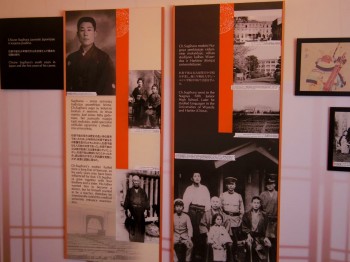

I visited the above house in Kaunas, Lithuania last month. In 1940, this house was the Japanese consulate. Kaunas functioned as the capital city of Lithuania prior to the Second World War. The Lithuanians considered Vilnius to be their rightful capital, but it was masquerading as the Polish city of Wilno at the time. Upon the German occupation of Western Poland and the Soviet occupation of Eastern Poland in late 1939, many (both Polish and Lithuanian) Jews were trapped in Lithuania and clearly in great danger, but were unable to gain exit visas to leave the Soviet Union (or travel across it by the Trans-Siberian railway) unless they had visas to go somewhere else. There were Japanese government rules stating that transit visas could be issued to Japan, but only if the applicant had plans to go somewhere else after Japan, and also that he had adequate financial resources.

Seeing the desperation of the situation, and against orders, Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara issued Japanese transit visas to anyone who asked. (In the book Bloodlands historian Timothy Snyder – who clearly finds Sugihara as fascinating a figure as I do – makes it clear that Sugihara was a Japanese spy as well as a Japanese consul, and his job was to keep track of Soviet troop movements for the Japanese government). During September 1940 he spent something like 20 hours a day writing out visas. When the consulate was closed and he had to leave, he was followed by a crowd to the railway station. As his train left, he was still throwing blank visas with his seal and signature on them to a crowd of desperate people. In total, he wrote something like 3000 visas, and as dependent family members could travel on the same visa as the principal person it was written for, those visas covered several times that number of people.

Kaunas railway station today. Kaunas railway station today.

Upon receiving these visas, Jews were able to travel on the Trans-Siberian railway to Vladivostok and then go by ship to Japan. They then dispersed to various places, but many were deported to Shanghai when the tripartite pact with Germany was signed shortly afterwards. Shanghai was also under Japanese occupation, and there these people spent time in the Shanghai ghetto – Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees – where they stayed until Shanghai was liberated by the Americans in 1945. I visited the remnants of the Shanghai ghetto in 2006, and wrote about it at the time. Although this was crowded and at times squalid, it was a place of relative safety. The Japanese behaved monstrously towards certain other groups, but they had nothing against Jews, and did not turn the Jews in Shanghai over to the Germans despite German requests. Rather cleverly, Jewish leaders in Shanghai played upon Japanese mistrust of their German allies. Upon being asked by a Japanese governor why the Germans hated the Jews so much, rabbi Shimon Sholom Kalish replied “They hate us because we are short and dark haired”.

Most Jews who got to Shanghai survived, and then emigrated to Israel, Australia, the US and other places after 1945. Estimates of the number of lives saved by Sugihara go as high as 10,000, although estimates of about 6,000 seem more common.

Half of the building in Kaunas is now a museum to Sugihara. I wanted to see this – it was why I went to Kaunas. The other people in the museum when I went there were a busload of Japanese tourists. Almost everyone who had signed the guest book had done so in Japanese, too. I didn’t see any Lithuanians or many other Europeans, which is a shame given this extraordinary story.

It’s an exceptionally good thing that the museum is there, but I did find the tone of the museum to be slightly curious. The museum did seem to be going out of its way to present the Japanese in general in the best possible light overall, rather than simply telling the story of Sugihara. That Sugihara was acting against orders was mentioned but not emphasised, and much was made of Jews who reached Japan being treated well, but not much was said about where they went after the Japanese alliance with Germany intensified and they were deported from Japan. The truth – the Shanghai ghetto mentioned above – doesn’t actually reflect too badly on the Japanese, but it is rather unfortunately connected to other things that do reflect badly on the Japanese. It is impossible to praise Sugihara himself too much – the man saved the lives of 6,000 or more people just out of basic human decency – but does this reflect well on Japan as a whole? That is harder to say. As is the case with other various people who did similar things, his story remained obscure for many years. His career with the Japanese foreign service ended after the war for reasons that may or may not have had to do with disobeying orders in Lithuania.

Eventually, Sugihara’s story became widely known, and he was later honoured by Yad Vashem, the state of Israel, the state of Japan and the state of Lithuania, but this took a long time. As it did with Paul Grüninger, Oskar Schindler, and others.

Forces of an offshoot of Al-Qaeda advance on Baghdad

“Blame Bush!” “Blame Blair!”

Can anyone explain to me why the starting point for anything newsworthy that Muslims do is eternally set at 2003?

Why not September 11th 2001 – one might have thought that was the big day this century for violent beginnings connected with Islam? Or why not date it from 1988, with the formation of Al-Qaeda? Or from the year 622, first year of the Hijra – if you take a long view of history, as ISIS themselves undoubtedly do? Or why not start the count later? How about late 2011 when President Obama took the last American troops out of what he called a “a sovereign, stable and self-reliant Iraq” just “in time for the holidays”?

Not that it is likely, as Muslim Iraqi fights Muslim Iraqi in a land from which the infidel was so delighted to absent himself, that comabatants on either side think much about American presidents at all.

Ten years ago today I tried my hand at alternate history with a post whose title was taken from the words General Eisenhower prepared for use in the event that the Longest Day had ended in defeat: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold.”.

Here is an earlier effort in the same genre – a German newsreel made, I would guess in late June 1944. It mentions stiff fighting around Caen, but since Caen did not fall to the Allies until late July, that does not narrow the date down much.

The claim made at 2:07 that infantry assault troops were “airlifted in for the first night of the engagements” is false. The Allies owned the skies. Nor do I believe that the “German wartime fleet” ever gave the “signal for resistance” (as claimed at 2:46), or any other signal at that time and place.

It would have been a remarkable stroke of journalistic good fortune to have happened to be filming when the first news of the invasion came and to have captured the moment when soldiers grabbed their rifles, so I guess what we saw one minute in was a drill. The numerous shots of explosions and guns firing could have been filmed at any time during the war, although they may show real combat. Film of men looking through binoculars and speaking into microphones in a resolute manner is best obtained on days when little else is being done.

Since reality did not grant German soldiers an opportunity to stroll around abandoned Allied landing-craft on the beaches of Normandy, I think the shots shown at 5:16 (just after the picture at 5:13 of an SS soldier who looks oddly like Barack Obama) must be of the aftermath of the Dieppe Raid of August 1942. Given the great losses the Canadians suffered that day I initially thought the film at 8:25 of Canadian prisoners from the North Nova Scotia Highlanders was also taken after that operation, but Wikipedia makes no particular mention of soldiers from Nova Scotia taking part in the Dieppe Raid, whereas the North Nova Scotia Highlanders are listed as having taken part in the Canadian D-Day landing at Juno Beach. I now think that last part of the film is mostly true.

The panning shot at 3:16 of the invasion fleet itself – impossible not to admire the steady nerves of the German cameraman who took that – looks as if it really does depict that vast armada coming “straight for me”, as Major Pluskat famously told his superiors, and I cannot see how the pictures of downed gliders could show anything but the real price paid by the D-Day vanguard.

I see no particular reason other than the general mendacity of the Nazis to disbelieve the section showing the fighting around Caen. There was plenty of time for film really taken then to have reached Berlin and be made into a newsreel. The announcement at 7:09 that the men shown surrendering “are all surprised that the invasion is over so quickly” turned out to contain a wrong assumption, but one that might have been believed at the time.

Many Samizdata readers know much more than I about military history – including the Samizdata reader to whom I am married – and I expect some of them will make better informed judgements than mine as to the actual origin of some of the scenes in the newsreel. Let us be glad that we can look back at these images with the tranquility of the historian in a society that, unlike the Nazis, still cares, if diminishingly, for objective truth.

For a view of D-Day from the German side that strove a little harder to be honest, see Von Rundstedt’s report for distribution to commanders.

And remember those Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen who died. Their comrades who survived are mostly entering their nineties now and vanishingly few will live to assemble on the beaches for any big anniversary after this.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|