We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Hat tip to “bloke in spain”, who pointed out this article by Dr Helen Pankhurst in the Telegraph:

95 years since its first female MP, Britain is lagging behind.

We brag about our democracy, but women are still less represented in our legislature than in Kyrgyzstan, China, Rwanda and Sudan

“Now there’s a list of democracies to regard with awe & envy,” said bloke in spain.

Before I turn to the article, a word about the author. At the bottom of the piece there is a note saying, “Dr Helen Pankhurst is the great-granddaughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the original Suffragettes, and a special adviser on gender equality at CARE International UK.” If you were wondering, CARE International UK is a charity adequately described by the fact that it has a special adviser on gender equality and Emmeline Pankhurst was a great name in the fight for women’s suffrage, and, equally admirably, though this is less celebrated in the history books, a pioneer in the struggle against Bolshevism.

It is heartening to see Dr Helen Pankhurst gain entry to the pages of the Telegraph on the strength of the name of her great ancestress, thus upholding the hereditary principle in these Jacobinical times.

She writes,

Ninety-five years ago today, on November 28, 1919, an American became the first woman in Parliament. Technically, she had been beaten to it the previous December by the countess Constance Markievicz, an Irish nationalist who fought and won her campaign for Dublin St Patrick’s from Holloway Prison. But Sinn Fein, her party, was boycotting Parliament, and with them she refused her seat.

So it fell to Lady Nancy Astor to enter the House of Commons as its first female member (and first female Conservative), succeeding her husband in the by-election triggered by his ascent to the Lords. It was one year since the Act of Parliament which had given propertied women over 30 the right to vote and stand. She would serve her constituency of Plymouth Sutton for another 26 years.

Yet since then the progress for women’s representation has been slow. Until 1987 women represented less than five per cent of MPs; this doubled in 1992 then doubled again to 20 per cent in 1997. Even now, nearly a hundred years after the initial Act, only 23 per cent of representatives in both houses are women. Will it take until the 200th anniversary of Lady Astor’s election before we write about equal representation as if it were business as usual?

I disagree that the progress for women’s representation in the United Kingdom has been slow since 1919. Progress was quite fast between 1919 and the passing of the Representation of the People Act 1928, when women gained the vote on the same terms as men, and nonexistent since then. Progress has been nonexistent for the excellent reason that there was no more progress to be made. Once women and men had equal rights to vote or stand for office they were equally well represented by being represented (not duplicated) by whatever representative they had voted for. You know, voting for your unrestricted choice of candidate, like you do in a representative democracy. One of the things you’re allowed to do is vote for someone not like you in the nether regions. This innovation seems to have worked out OK since 1919; I think we might keep it on. Does Dr Pankhurst think that Lady Nancy Astor MP was incapable of representing her male constituents?

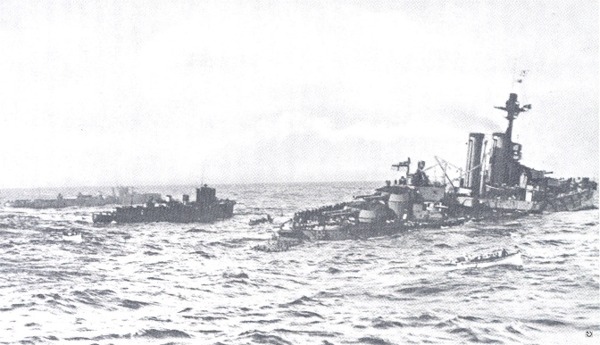

On 27 October 1914 HMS Audacious, one of the Royal Navy’s newer battleships hit a mine and sank. The government censored the story and the loss wasn’t officially admitted until after the war had ended. This is about as close as readers of the Times got to hearing about it officially:  The Times 6 November 1914 p4 The point being that the Olympic (sister ship of the Titanic) helped in the rescue operation. Many of its passengers were Americans and some even took photographs. As there was no censorship in America news of the sinking slowly filtered across the Atlantic. There’s a good discussion about the sinking here:

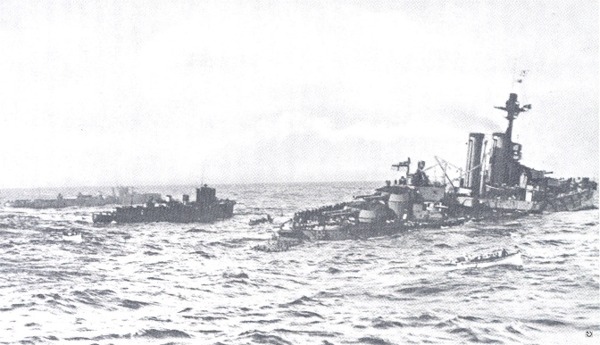

So, why the secrecy? Partly this was because of where the Audacious sank. The fleet was supposed to be in Scapa Flow in the Orkneys guarding the North Sea. However, due to the state of the submarine defences there it was thought prudent to move it to Lough Swilly off the northern coast of Ireland. The navy did not want the idea to get out that the North Sea was an open house.  HMS Audacious sinking But there may have been another reason. The early months of the war had been a disaster for the Royal Navy. The German battlecruiser, Goeben, had evaded the British in the Mediterranean and went on to play a large part in bringing Turkey into the war. Three cruisers, the Hogue, Aboukir and Cressy had managed to get themselves sunk by the same submarine in the Channel in the space of an hour and a half. At the battle of Coronel a British cruiser squadron had attacked a superior German force with disastrous results. In the southern oceans the commerce raider Emden was making fools of its pursuers, seemingly able to pop up out of nowhere to shell ports and destroy wireless stations. There may have been a desire not to admit just how badly things were going.

In situations like this questions are bound to be asked about the man at the top – or the First Lord of the Admiralty to give him his grand, official title – but it would take another year and more disasters before he would finally be sacked. The chap’s name? Oh yes, Winston Churchill.

Back in the bad old days, Kremlinologists used to try to figure out what was going on in the leadership of the USSR by observing signs and portents.

During the Cold War, lack of reliable information about the country forced Western analysts to “read between the lines” and to use the tiniest tidbits, such as the removal of portraits, the rearranging of chairs, positions at the reviewing stand for parades in Red Square, the choice of capital or small initial letters in phrases such as “First Secretary”, the arrangement of articles on the pages of the party newspaper “Pravda” and other indirect signs to try to understand what was happening in internal Soviet politics.

To study the relations between Communist fraternal states, Kremlinologists compare the statements issued by the respective national Communist parties, looking for omissions and discrepancies in the ordering of objectives. The description of state visits in the Communist press are also scrutinized, as well as the degree of hospitality leant to dignitaries. Kremlinology also emphasizes ritual, in that it notices and ascribes meaning to the unusual absence of a policy statement on a certain anniversary or holiday.

Brian Micklethwait has often written of the “sovietisation” of various parts of the British State such as state schools and the NHS. To illustrate this process, take a look at the way a “major incident” at Colchester Hospital has been reported.

What major incident you ask? My point exactly: you ask, they don’t answer. Likewise “safeguarding” is repeatedly mentioned. Something needs to be safeguarded.

Late last night or early this morning there were oracular bulletins from the Telegraph and Times, all chock-full of unspecified “incident”. From the Times:

On Wednesday, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspected Colchester Hospital’s accident and emergency department and emergency assessment unit and told trust it had concerns over “safeguarding” there.

The major incident is likely to last for a week, and the trust has reminded members of the public to only visit A&E if they have a “serious or life-threatening condition”.

A spokesman for the hospital said the inspection was not the sole reason for the major incident being declared, although it played a role.

All clear now? There was a similarly opaque article on the AOL homepage. It has been updated since, as has the Telegraph one, I think, but the Times, like a good horror movie, is delaying the big reveal.

The BBC followed suit: “Colchester Hospital declares major incident.” The BBC did tell us what sort of general thing might constitute a “major incident” but not about this major incident. As a result everyone thinks it’s ebola and as I write this it’s the most looked-at article on the BBC website.

Stand down. It’s not ebola. The Guardian was slow to get the story but does actually tell it:

A major incident has been declared at Colchester hospital after a surprise inspection this week found patients being inappropriately restrained and sedated without consent and “do not resuscitate” notices being disregarded.

The ward concerned has been closed to new admissions, an emergency control centre has been put in place to address capacity problems, and patients are being urged to go to A&E only if they have a serious or life-threatening condition.

Inspectors from the Care Quality Commission (CQC) found that the Essex hospital is struggling with “unprecedented demand”, but the Guardian understands concerns were also raised about safeguarding issues relating to inappropriate restraint, resuscitation and sedation of elderly people, some with dementia.

Oh dear, what a let down. Just as it used to in the days of Pravda and Izvestia the secrecy concealed mundanity. It’s just the NHS in crisis again. Can’t they do anything right? The zombies they make aren’t even dead yet.

Nigel Farage: the armistice was the biggest mistake of the 20th century

Farage is quoted as saying,

“But had we driven the German army completely out of France and Belgium, forced them into unconditional surrender, Herr Hitler would never have got his political army off the ground. He couldn’t have claimed Germany had been stabbed in the back by the politicians in Berlin, or that Germany had never been beaten in the field.”

Most of the Guardian commenters take this as proof of Farage’s bigotry and ignorance.

“That’s because he wasn’t doing the fighting. Even if he was alive at the time, little silver spoon establishment posh boys don’t do the fighting anyway. They send others to their deaths,” says commenter “steemonkey”, getting lots more recommends than the reply from “FenlandBuddha”:

“Actually the upper classes suffered worse proportionally than anyone else because you were more likely to be killed as a junior officer than a private. The Prime Minister Asquith lost one son, the Conservative leader Bonar Law lost two.”

Sir Thomas died on November 6th and so just missed having his Times obituary appear on Armistice Day. He was 94. There will not be many more obituaries like this.

The Jedburgh team of which Major Macpherson was in charge, codenamed “Quinine”, was flown from Blida in Algiers and dropped near Aurillac, in the Cantal department, on the night of June 8, 1944. Accompanied by Aspirant (officer cadet) Prince Michel de Bourbon of the French Army and Sergeant Arthur Brown of the Royal Tank Regiment, Macpherson — a proud Scot — wore his kilt for the occasion. The attire caused some confusion and the first report to reach the local maquisards claimed “a French officer has arrived with his wife”.

In order to swell partisan numbers, Macpherson drove around in a car — still wearing his Cameron Highlander tartans — openly flying the Union Flag pennant and the Croix de Lorraine, much to the astonishment of his comrades

Whether through bravery or chutzpah, Macpherson won the surrender of 23,000 Wehrmacht troops by spouting a series of brazen lies. He presented himself to the commanding officer, Major-General Botho Elster, and assured him that heavy artillery, 20,000 troops and RAF bombers were waiting for Macpherson’s word to attack. In reality he had only the aid of another Jedburgh team. Surrender or die, he urged Elster; the bluff worked. Elster and his troops eventually passed into US Army captivity.

. . . Macpherson won an athletics Blue and could even boast a rare victory over Roger Bannister.

Oxford eased him back into civilian life — “Our life was finished, and then it started again”. For nearly 30 years he worked for the timber company William Mallinson & Sons, where he started as a personal assistant to the chairman and finished as managing director.

As children they recall their father beginning every day with a cold bath and an hour of exercise.

He published an autobiography, Behind Enemy Lines, in 2010. Once asked to name his proudest moment, he pondered and said: “It’s very often that one remembers the small things and forgets the big ones.”

Twenty five years ago today, the crossings between East and West Germany, most notably at the Berlin Wall, were opened, and shortly thereafter, the last of the Marxist regimes in Europe ended.

The Berlin Wall was a symbol of the depravity and viciousness of the Marxist idea. Karl Marx was a pure hate monger masquerading as a social philosopher. His ideas may, in the end, be summarized thus: wealth can be gained only by stealing from others, and thus successful people are evil, and thus it is okay to threaten or kill rich people (or even people who are just a bit better off than you are), to steal their belongings, and to threaten anyone who might in the future have more stuff than you do. If you somehow get more things than other people, it is okay for other people to take your stuff, and if you resist, it is okay to beat you up or kill you.

Even more succinctly, Marxism is the idea that envy is laudable, and should be turned into social policy with the use of pervasive violence.

I am putting this more bluntly and baldly than the average Marxist would. They prefer concealing their central idea beneath a heavy blanket of words. They dress up their “philosophy” in avant garde costumes, adding layers of verbiage, complicated and counterfactual claims about language and logic, bizarre ideas about the nature of history, etc., all in the service of keeping people from seeing what they’re actually suggesting. What lies underneath is nothing much more than hate of people who have more stuff than you do, justified by little or nothing more than wanting to take what they have for yourself.

When you base your beliefs on this sort of foundation, the violence that proceeds is not an accident or the result of an improper understanding or implementation of an otherwise fine program. The violence is the direct and intentional result of the underlying program. The violence is the entire purpose of the underlying program.

In spite of the claims of apologists, the Marxism that fell twenty five years ago was the true Marxism. You cannot force people to work whether they get any benefit of it or not if they can flee from you, so you have to build walls. The Berlin Wall was not an aberration, it was the the only way to keep the quite literal slaves from fleeing their bondage. You cannot take stuff from people who have it without goons with guns, since they will not want to hand their material possessions over, so you bring in goons with guns to scour your population. In a free market, you get ahead by making things people want like bread or telephones, but in a Marxist society, the only way to get ahead is through gaining political power, and so people who are exceptionally talented at deploying violence and thuggery and are ambitious rise to the top of your society. Stalin or someone like him was not an accident, he was an inevitability.

What is shocking but sadly unsurprising to me is this: after a seventy year experiment that lead to a hundred million deaths, we still have people in our universities and even on our streets who profess to be Marxists.

There are, everywhere, professors who teach a Marxist interpretation of history, of literature, of economics and sociology, and not merely for some sort of historical perspective, but as an actual active ideology they would like their students to adopt. It is, indeed, an entirely ordinary sort of thing, so common it is not even worthy of note. There are people who wear Che Guevara T-shirts in the streets, never mind the people Guevara ruthlessly executed, including children, in the name of Marxism.

Would it be considered equally ordinary for a professor to be out teaching the Nazi interpretation of literature or social interactions, and encouraging their students towards adopting the Nazi point of view? Would people feel equally unmoved by people walking around wearing a Joseph Goebbels shirt?

Note that I do not suggest censorship. That is not the point. What I am instead suggesting is that, to this very day, our culture has not yet absorbed the lessons of Marxism, has not come to terms with the fact that it was not a noble experiment that failed, but rather a monstrous calamity that needs to be understood for what it was, lest it happen again.

The Berlin Wall was breached 25 years ago today. The New York Times has an article about those for whom it came too late: On Berlin Wall Anniversary, Somber Notes Amid Revelry

BERLIN — It was the morning after the best party ever, the tumult and joy that marked the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989. After 28 years, East Berliners were giddy with marvel that they could now visit the West.

Günter Taubmann felt different, as if, he said, “I am in the wrong movie.” Eight years earlier, his only child, Thomas, had been killed trying to cross the wall, one of 138 people who died at the barrier erected by the Communists in 1961 to stop Germans streaming out of the poor, repressive East.

ADDED LATER: Re-reading the New York Times article to which I linked above, something about the reference to one of those killed attempting to escape, Marinetta Jirkowski, being shot 27 times, triggered a memory. I dug out from our bookshelves a collection of Bernard Levin’s columns for the Times called Speaking Up. Here is what he wrote in a column dated 22nd January 1981:

For a week or so ago there was a report, so irrelevant to the world’s concerns that I could find no trace of it any newspaper other than the Daily Telegraph, where it was recounted in exactly fifty words, which tells a story often recounted by me in the past and no doubt even more often to be repeated by me in the future.

A pregnant girl of eighteen – we even have her name, Marinetta Jirkowski – was shot dead by East German border guards while trying to escape to the West with two men. The two men survived, and got to freedom; Fräulein Jirkowski did neither, but fell dead with nine bullets in her.

[…]

We have supped full of horrors these past few decades, and the worst result of such a diet is not indigestion but loss of appetite. And yet it seems to me that even if we have to hold our noses and make a face as we swallow, sup we must. For what lies upon our plate is the knowledge that some things are evil – evil sans phrases – and that what was done to Marinetta Jirkowski is one of those things.

As you will have noted, Mr Levin had underestimated the number of bullets that struck Marinetta Jirkowski. Other than that his assessment was accurate.

Levin’s column continued,

And so I feel it necessary to bang my head against the wall again today, upon the strange death of Marinetta Jirkowski. I do not know how the filthy thing that killed her is to be destroyed, though I know that sooner or later it must be. I do know that there are people in this country who admire that thing, and wish it to rule us, too, and some of them are in our universities, and some in our press and television, and some in the councils of our trade union movement, and some in Parliament, and many of them hardly bother any longer to pretend that their beliefs are other than they are, which suggests that they think they are near their goal; and in so thinking they may well be right.

How strange it is to read those words in conjuction with Perry Metzger’s post above. The particular avatar of the filthy thing that killed Marinetta Jirkowski was nearer to its destruction than Levin had dared hope when he wrote that column. It is gone. But the intellectuals and the media “personalities” who admire it are still there. As Perry wrote,

There are, everywhere, professors who teach a Marxist interpretation of history, of literature, of economics and sociology, and not merely for some sort of historical perspective, but as an actual active ideology they would like their students to adopt. It is, indeed, an entirely ordinary sort of thing, so common it is not even worthy of note. There are people who wear Che Guevara T-shirts in the streets, never mind the people Guevara ruthlessly executed, including children, in the name of Marxism.

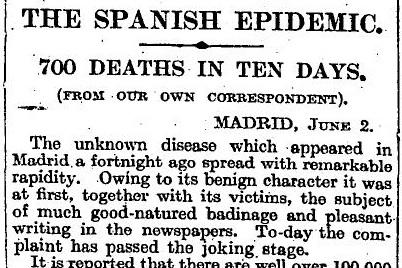

This is how in 1918 Times readers first found out about Spanish flu:

The Times 3 June 1918 p5

You can say that again. It ended up killing 40 million people.

Incidentally the Wikipedia page on the subject is an appalling mess. At one point it claims that it began on the Allied side of the front, at another that it began on the Central Powers’ side. At one point it claims that it was particularly lethal to those with strong immune systems and at another to those with weak immune systems.

Having said that I love the suggestion that it was called Spanish flu because that was the origin of the first reports of the disease. It was the origin of the reports not because it was the first place to get the disease but because wartime censors did not want to encourage the enemy by admitting its presence.

So, it’s possible that this was not how Times readers first found out about it.

The story of the First World War so far: Germany pushed the bulk of its army through Belgium. The French, along with the tiny British army were unable to hold them and retreated. At the Marne the Germans were stopped and themselves began to retreat. At the Aisne they stopped retreating, dug in and trench warfare began. People are beginning to realise it’s going to be a long war.

However much we may hope to bend back the German right and relieve Antwerp [they didn’t]; whatever confidence we may entertain that the shock of the Russian masses in the East may soon prove decisive [it didn’t], we must not entertain the slightest illusion regarding the hard and trying conditions which await all the Allies in their future operations against a Germany reduced to the defensive. Germany is still united and her resources are great. All her men are in arms and all her arsenals are working at full presssure. Her unbeaten fleet and flotillas will strike when their hour comes, and probably in cooperation with her Army. The line of the Aisne, even when forced, may prove only one of many similar lines which are being prepared to the rear of it… and it may take long, very long, for the Allies to compel Germany to experience the sense of her weakness.

In other words, it’s not going to be all over by Christmas. [Not that I have actually come across that phrase in the pages of The Times.]

The writer, himself is worth a mention. He is The Times’s Military Correspondent, a chap by the name of Charles à Court Repington. A talented officer with a bright future, he was chucked out of the army for conducting an affair with a married woman. The army’s loss was The Times’s gain. While no one can predict the future with perfect clarity, Repington did a pretty good job of it as he does above. In 1913, he predicted that Germany’s main thrust would come through Belgium. The French high command did not work that out until late August 1914 when it was almost too late.

The Times 3 October 1914 p5

Starting on 1st August, 1944, the Polish Home Army resistance rose against Nazi Germany in Warsaw, mounting what was by far the largest single military effort by a European resistance movement in World War 2. The advancing Soviet Red Army halted and waited for the German Army to completely crush Polish resistance and did not lift a finger to help, even though it had air force assets less than five minutes flight time away from where the Poles fought and died, light infantry weapons and a few captured heavy weapons against tanks and artillery. The Soviets quite literally watched and did nothing, refusing requests by the Western Allies to use Soviet airbases to provide assistance to the Poles. More than two hundred long distance supply drops were conducted by the RAF in spite of Soviet opposition, but were completely inadequate for the needs of the defenders.

However as the Polish Home Army was loyal to the Polish government-in-exile in London, the Soviets saw it as an obstacle to their intentions to turn Poland into a communist puppet state, and were delighted to have their former ally but now bitter enemy Nazi Germany eliminate this politically inconvenient group.

Starting on 16th September, 2014, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and elements of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) began defending the town of Kobani from the Salafist forces of the Islamic State, light infantry weapons and a few captured heavy weapons, against an enemy who have heavy weapons and copious munitions that they acquired in Iraq, when the Sunni elements of the Iraqi Army either changed sides or simply abandoned their depots and ran away. Also early on in the Syrian Civil War, what was to become the Islamic State gained material support as part of the resistance movement against the Syrian Government, from Turkey under its politically Islamist leader Tayyip Erdogan.

The largely Kurdish defenders of Kobani in Syria are associated with Turkish Kurdish nationalists of the Marxist PKK, and thus the Turkish army are quite literally watching from across the border from within small arms range, as Kobani’s defenders are being crushed in bitter street fighting by the numerically superior and better armed Islamic State.

The Islamist government of Turkey is really not that concerned by the Islamic State, and so they are quite happy to see them crush the politically inconvenient and politically secular Kurdish nationalists in Kobani. Turkey has refused requests for NATO aircraft to use Turkish airbases, and the mostly American strikes have failed to prevent the Islamic State from forcing their way into the town at the time this article is being written.

The parallels are striking.

One of the many felicities of Bill Bryson’s At Home: A Short History of Private Life, which I am currently engaged in reading and am enjoying greatly, is that noted warriors and statesmen do get mentioned, but for their peacetime activities.

The Duke of Wellington, for instance, gets just the two brief mentions, on page 128, for his habit of consuming a very large breakfast, this being an illustration of the then breakfasting habits of rich personages generally, and before that on page 49, when in his dotage Wellington was in nominal charge of an army of militiamen whose task would have been to quell any revolutionary outrages that the masses gathered for the Great Exhibition of 1851 might have felt inclined to perpetrate, outrages which were greatly feared at the time but which never materialised.

Concerning two big military and political movers and shakers on the other side of the Atlantic, Bryson has more to say, because they, unlike Wellington, made two very impressive and influential contributions (Jefferson’s Monticello and Washington’s Mount Vernon) to the art of domestic architecture, and in consequence to architecture generally:

Had Thomas Jefferson and George Washington merely been plantation owners who built interesting houses, that would have been accomplishment enough, but in fact of course between them they also instituted a political revolution, conducted a long war, created and tirelessly served a new nation, and spent years away from home. Despite these distractions, and without proper training or materials, they managed to build two of the most satisfying houses ever built. That really is quite an achievement.

Monticello’s celebrated contraptions – its silent dumbwaiters and dual-action doors and the like – are sometimes dismissed as gimmicks, but in fact they anticipated by 150 years or so the American love for labour-saving devices, and helped to make Monticello not just the most stylish house ever built in America but also the first modern one. But it is Mount Vernon that has been the more influential of the two. It became the ideal from which countless other houses, as well as drive-through banks, motels, restaurants and other roadside attractions, derive. Probably no other single building in America has been more widely copied – almost always, alas, with a certain robust kitschiness, but that is hardly Washington’s fault and decidedly unfair to his reputation. Not incidentally, he also introduced the first ha-ha into America and can reasonably claim to be the father of the American lawn; among all else he did, he devoted years of meticulous effort to trying to create the perfect bowling green, and in so doing became the leading authority in the New World on grass seed and grass.

It is remarkable to think that much less than a century separated Jefferson and Washington living in a wilderness without infrastructure from a Gilded Age America that dominated the world. At probably no time in history has daily life changed more radically and comprehensively than in the seventy-four years between the death of Thomas Jefferson in 1826 and the beginning of the following century …

A “ha-ha”, in case you are wondering, is a fence set in a ditch, which works as a regular fence for impeding animals, but which doesn’t spoil the view.

Concerning those “proper materials” that Washington and Jefferson lacked, I particularly enjoyed reading (pp. 424-8) about the infuriations suffered by rich pre-revolutionary Americans when trying to get Brits to send stuff over to America for them to build and furnish their houses, in sufficient quantities, of the correct sort, not ruined in transit, and for a non-extortionate price. The Brits insisted that everything that Americans bought from abroad had to go via Britain, even stuff originating in the West Indies. Of this draconian policy, Bryson says (p. 428):

This suppression of free trade greatly angered the Scottish economist Adam Smith (whose Wealth of Nations, not coincidentally, came out the same year that America declared its independence) but not nearly as much as it did the Americans, who naturally resented the idea of being kept eternally as a captive market. It would be overstating matters to suggest that the exasperations of commerce were the cause of the American revolution, but they were certainly a powerful component.

Despite such things as the dramas now going on in the Ukraine and in the Middle East, most of us now live amazingly peaceful and comfortable lives, when compared to the hideously warlike and uncomfortable lives lived in the past. That being so, more and more of us are going to want to read books like this one by Bryson, about how life became as comfortable as it now is, who contrived it, and how, and so forth and so on. We are now becoming the kind of people who attach more importance to things like why forks are the way they are, or why wallpaper started out being poisonous, or how vitamins were discovered and itemised, or how farming got better just when big new industrial populations needed more food, or how gardening became such a huge hobby or how meat, fruit and vegetables first got refrigerated, than we do to such things as the details of the Duke of Wellington’s or George Washington’s battles.

All this peace and comfort may turn out to be a mere interlude, if all-out war between Great Powers is resumed, and if that happened, the people in the formerly comfortable countries, like mine now, would soon rediscover any appetite they might now be losing for learning about war rather than about peace. But despite recent claims that our times resemble those just before WW1, I personally see little sign of a real no-holds-barred Great War erupting soon between two or more Great Powers. Putin is not Hitler reborn and Russia now is not 1940s Germany; the Muslims are mostly killing each other rather than us; and attacks with H-bomb barrages remain as utterly terrifying now as they have been ever since they were first made possible.

For the unlettered among you, the heptarchy is a collective name for the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros, Dorne, the Kingdom of the Isles and Rivers, the Kingdom of Monuntain and Vale, the Kingdom of the North, the Westerlands or Kingdom of the Rock, the Kingdom of the Reach, and the Kingdom of the Stormlands …

Bzzzt! Reset!

The heptarchy is a collective name for “the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, conventionally identified as seven: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms eventually unified into the Kingdom of England.”

Like you care? You should. Following the vow made to the Scots by David Cameron in order to win the referendum of devo max to the limit of my credit card, the West Lothian question has come back to bite him.

The West Lothian question is easy to ask and almost impossible to answer. As posed in 1977 by Tam Dalyell, former MP for the Scottish constituency, it demands to know why MPs from Scotland (and now Wales and Northern Ireland) should be able to vote on issues such as health and education that affect England when English MPs have no power to vote on social and other policies that are devolved to the parliament in Edinburgh (and now also the assemblies in Cardiff and Belfast).

Because welfare issues are devolved, members of the Westminster parliament elected from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have no power to decide how these policies should affect their constituents; ironically, they can vote only on welfare issues as they affect constituencies in England.

One solution to this might be simply to have the same type of devolution for England as is already present for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. (Yes, I know that the arrangements for all three regions differ, but I’m just thinking in broad terms.) The trouble with that is that England has a population of 53 million as against Scotland’s five million, Wales’ three million and Northern Ireland’s 1.6 million. Quoting the same Guardian article by Joshua Rozenberg on the West Lothian question as above,

Vernon Bogdanor, research professor at the Institute of Contemporary British History at King’s College London, pointed out recently: “There is no federal system in the world in which one unit represents more than 80% of the population … Federations in which the largest unit dominated, such as the USSR, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, have not been successful.” He also points out that there would be little appetite for a new English parliament, separate from Westminster.

So maybe we could split England up into smaller electoral regions for the purpose of voting on English matters? It has been tried. Almost nobody wanted it. Only the proposed North East England Regional Assembly ever appeared to have anything like enough support for anyone even to bother putting it to a vote, and the proposal was decisively rejected. The main reason for that rejection was that voters saw it as just another layer of politicians and bureaucrats whose salaries and fancy offices would have to be paid for out of their taxes. A less well-articulated but still significant reason was the feeling that it was all a plot to Balkanize England hatched by the European Union and England’s oikophobic elite. Which it was, though probably not one made consciously. Yet another reason was that the proposed regions were cultivated in a petri dish and hatched from a test tube. Many have loved the north east of England but nobody has ever loved “North East England”. No poet has ever penned such stirring lyrics as “To arms, citizens! Will ye stand back when enemies imperil our Regional Unit?”

It is an attractive idea to bring back the traditional counties of England. It is also an attractive idea to dig up the body of the man who abolished them, Edward Heath, and stick his head on a pike, but that won’t happen either. The counties are just too small.

So if we are to have petty kingdoms, let them at least be kingdoms. Men have loved the Kingdom of Mercia. Men have died for the Kingdom of East Anglia – notably at the hands of men of Mercia, but there you go. Men of all the ancient nations of the Saxon have followed the greatest of the Kings of Wessex to glorious victory against the Vikings. Divide and conquer that, Eurocrats! Also it would serve the Vikings right for subjecting me to all those irritating pictorial instructions.

Sorry, Scotland, I’m afraid that the contemporary Kingdom of Strathclyde will not be restored to the full extent of its ancient holdings where they stretch into modern England. As in post-colonial Africa, for the avoidance of bloodshed the external borders established by the imperialism of the Kingdom of Alba must remain in place. Whether Scotland should restore its own ancient sub-kingdoms within its present borders is naturally a devolved matter.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|