We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

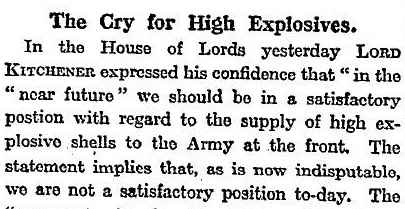

It’s been an interesting couple of months a hundred years ago. There have been the landings at Gallipoli, the German use of gas at Ypres, the imminent departure of both the First Lord of the Admiralty and the First Sea Lord, the failure of the British attack at Aubers Ridge and the “Shell Scandal” – the claim that the Aubers failure was due to a lack of shells. Meanwhile, the Lusitania has been torpedoed, Zeppelin raids are continuing and the Bryce Report into alleged German atrocities in Belgium has concluded that most of the allegations are true. In shades of the London riots of 2011 – demonstrators have asserted their right to protest at the uncivilised behaviour of the German government and – additionally and in consequence – to steal and break the property of all those who have German names.

There are a couple of ideas going on here.

The first idea is that we – the British – are dealing with a ruthless and unprincipled enemy and that therefore we must at least be equally ruthless and possibly equally unprincipled. The second idea is that it is the state’s responsibility and privilege to lead and enforce British ruthlessness. There must be no more amateurism or muddling through. Everything must be systematic and uniform and directed from the top. Early signs of this change in approach will be the formation of a coalition government and the foundation of the Ministry of Munitions. Already there have been calls for conscription which is odd given that the New Armies raised in 1914 have yet to fight.

I suspect that, like most things that government does it didn’t work, or at least, worked no better than if they had left things to market or – given the central role of government in any war – near-market forces. However, he who wins gets to write the myths. And so the myth that government direction works got established in the UK. Probably.

The Times 19 May 1915. Talk about “The Thunderer”. I particularly like the reference to the “mutilated and twice-censored” Times article.

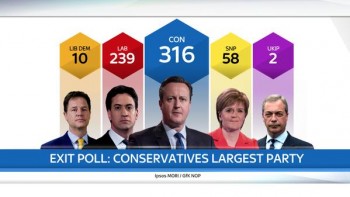

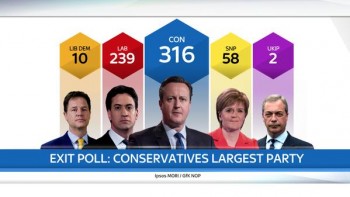

It is, as I type this, only a few hours since the polls closed, and this graphic is not the result of Britain’s General Election. It is merely a guess, based on asking people just after they had voted who they voted for. But, for what it’s worth, here it is:

I found it at the Guido Fawkes blog, which has been the pair of spectacles, as it were, through which I have mostly been viewing this now-concluded election campaign.

I have learned the hard way that what I hope for and what will happen in elections are not the same thing, not least because I tend to choose my electoral spectacles on the basis of pleasure rather than mere enlightenment. But the story told in the above graphic is very close to what I was and am hoping for, given the plausible possibilities or likelihoods that it made sense to be choosing between.

(What I would have liked, in a perfect, parallel-universe and wholly implausible world, would have been an election in which candidates were falling over themselves to offer swingeing tax cuts and competing about who could close down the most government departments and slash and burn the most in the way of government spending. All this, while the voters all stood around jeering, and saying: “Yeah, they say they’re going to slash and burn the public sector, but do they really mean it? They would say that, wouldn’t they?” Dream on, Micklethwait.)

The TV broadcasters have now been saying, for several hours now, that the Conservatives are doing significantly better than had been expected but not well enough to be truly happy because destined to occupy more Parliamentary seats than everyone else put together, that the Scottish Nationalists are engaged in sweeping Scotland and annihilating the Scottish Labour Party thus causing Labour, who are not doing well in England anyway, to do very badly indeed in the UK as a whole, that the Lib Dems are taking a hammering everywhere, and that the UK Independence Party is going to get a small mountain of votes, including a great many from Labour, but only a tiny molehill of seats.

The biggest story, as I watch my telly in the small but getting bigger hours of Friday morning, is the electoral earthquake (choose your preferred geological or climatological metaphor) that is erupting, exploding, sweeping across, engulfing, swamping, blah blah blah, … Scotland.

→ Continue reading: Scottish questions

[This is the text of a talk I gave on 20 March to the 6/20 Club in London. This is the final part. Part IV is here.]

Could the outcome provide a clue? Four monarchies: Germany, Austria, Russia and Turkey were swept away by the First World War.

When I say monarchy I am not talking about the wishy-washy monarchy we pretend to have in the UK. I am talking about real monarchies, monarchies red in tooth and claw, monarchies that can at minimum hire and fire ministers and start wars.

Now, I can almost hear the pedants shouting “But those are precisely the powers the Queen has” To which I say “Only in theory”. Should the Queen or any of her successors ever attempt to actually exercise those theoretical powers they would be out of office in a matter of nano-seconds. Britain is a republic.

When did it become one? I think we can be pretty precise with the dates: sometime between 1642 and 1694. 1642 is the date of the outbreak of the English Civil War, when Charles I tried to impose his idea of absolute monarchy. 1694 is the date William III accepted that his powers were extremely limited. Since then it has been Parliament that makes the laws and votes funding – without which making war becomes extremely difficult.

But think of what happened in that period: four civil wars, one military dictatorship and a foreign invasion.

You think that was bad? Try the French. Between 1789 and 1871 they saw four monarchies, three republics, three foreign invasions and a 20-year war with the rest of Europe.

And now look at what happened in the 20th century. Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, China, Turkey, Spain and Portugal all made the same transition from monarchy to republic. I need not dwell on the German or Russian experiences – they are well enough known but all the others follow a similar pattern. China saw a 20-year civil war followed by Mao’s communist regime; Spain, a monarchy, followed by a republic followed by a civil war followed by a dictatorship followed by a monarchy followed by a democratic republic. Even Portugal saw two revolutions, a dictatorship and a series of bloody colonial wars.

The point is that in every case the transition from monarchy to republic is bloody and protracted.

If there is an exception to the rule it is Japan. Japan is odd because in the middle of the 19th Century it had two monarchies. The one we know about – which was as powerless then as it is now – and the Tokugawa Shogunate. The downfall of the Shogun was remarkably swift and afterwards, as I understand it, Japan was pretty stable up until the 1920s. That’s about 40 years. But assuming Japan is an outlier and we have a pattern, then why the bloodshed?

My guess is that once a monarchy looks vulnerable and anachronistic thoughts turn to a future blank slate. This blank slate is an invitation for idealistic, Utopian and statist ideas to fill the vacuum. And so they do. Even England got the Puritans (and, I might add, the Levellers).

This process was in full swing well before the First World War broke out. The Revolution of 1905 had forced the Tsar to call a parliament. The largest party in the Reichstag, the German Parliament, was the Socialists.

There were two basic majoritarian ideas knocking about Europe at the time: socialism and nationalism. Monarchs can’t do much with socialism but it is just possible for them to embrace nationalism (unless they’re Austrian, that is). And so we see Europe from about 1890 on divide on nationalist lines. Russia and Germany started to become hostile. German politicians began to talk of a coming racial struggle.

This put Austria in a bind.

When he was single there was a time when Franz Ferdinand would regularly visit an eligible duchess. The assumption was that he was courting her and that the two would eventually marry. Not so. He was courting Sophie Chotek one of her ladies in waiting. Sophie was from a noble family herself but just not noble enough. The emperor was furious when he heard that the two wanted to marry.

In English we have a rarely used word, morganatic. So rarely-used is it that I have only ever heard it used in one context. This one. It means that in a marriage one of the partners and the children and not allowed to benefit from any of the privileges of the other partner. Franz Ferdinand and Sophie had a “morganatic marriage”. The children were not allowed to inherit Franz Ferdinand’s titles or status. They could not become Emperor or Empress. On state occasions Sophie could not accompany her husband. One of the reasons the couple loved England so much – their last trip was in 1913 – was that Sophie was granted the same status as her husband. One of the reasons Sophie was in Sarajevo on the fateful day was because it was one of the rare occasions on which she could accompany him. It was also their wedding anniversary.

I have often wondered about the significance of this. Why was the Emperor so furious about Franz Ferdinand marrying beneath him? I think the reason is that Austria-Hungary being a multi-national state could not embrace nationalism. The only unifying factor was the monarchy and so everything had to be done to preserve the mystique and uniqueness of the institution. As the Emperor might have seen it when royals start marrying lowly nobles pretty soon you give the impression anyone could do the job. Bye bye monarchy, bye bye empire.

Ultimately, no one is to blame for the First World War as such. The First World War is principally a chapter in the story of central Europe’s transition from monarchy to republic. As such the principal actors were subject to forces that were way beyond their ability – or indeed anyone’s ability – to control. Although, this does not entirely absolve them of blame it absolves them of a lot.

[This is the text of a talk I gave on 20 March to the 6/20 Club in London. See also Part III and Part V.]

Part of the reason the origins of the First World War are so controversial is that for a long time the history itself was a matter of contemporary politics. After the inclusion of the War Guilt Clause in Article 231 of the Versailles Treaty, the German government spent a great deal of effort in attempting to vindicate its predecessor’s actions. In a similar vein the communist movement spent a great deal of effort trying to prove that it had something to do with capitalism and imperialism.

The very fact that the debate is still ongoing and still so confused makes me think that there must be something missing.

One thing that tends to be missing from the debate is morality (although as I will explain that’s not going to do us an awful lot of good.) What I mean by that is a sense of right and wrong. What is reasonable for a state to do and what is unreasonable.

This poses some pretty obvious difficulties for libertarians. Violence is wrong. States are the institutions that claim a monopoly of violence. Therefore states are wrong. But, so what? they exist. And not all states are the same. Some states do more violence than others and some states act more reasonably than others. Secondly, you are allowed to defend yourself and others. (At least, I think you are.) The problem is that if you are British in 1914 and wish to defend Belgians the only way you can do that is through the British state.

I should point out that Belgians were attacked in 1914. Whatever, you make think of the tales of German atrocities – I tend to think they were substantially true – German rule still meant all sorts of restrictions on every day life, a vast decline in living standards and the taking of hostages.

Another way of looking at it is to look at states’ liberalness. In 1914 the UK and France were the most liberal states in Europe, Germany and Austria slightly less so and Russia a long way behind (but still a long way ahead of what followed it). In 1917, America, a very liberal state, joined the allies and Russia exited the war. So, from a libertarian point of view the good guys, or at least the less bad guys won.

But were the good guys acting justly? Or less unjustly might be a better way of putting it. To the best of my knowledge, while the UK may have had the largest navy in the world it was not using it to deprive anyone of their freedom. Similarly, Belgians and Frenchmen were under attack and Britons had the right to come to their defence.

What about the French? Pretty much their only concern was Alsace-Lorraine. But from a libertarian point of view the only thing that matters is the freedom of the people of Alsace-Lorraine.

This takes us more or less immediately to the Zabern Affair. The Zabern Affair began when a German officer based in Alsace said some rude things about the locals. The locals got to hear about it and there were riots. It revealed to Germans that the army had a legally privileged position and that the Reichstag was toothless and to Frenchmen that their countrymen were, well oppressed is perhaps too strong a word – looked down upon might be better.

So what about Germany? In the Christmas truce of 1914 some British and German soldiers got talking and the conversation turned to the subject of the war. The German explained that they were fighting for “freedom”. To which the Briton replied, “I’m terribly sorry but we are the ones fighting for freedom.” You wonder how the German could think such a thing. I think it was related to the idea that to be a serious state you had to have an empire; a place in the sun. Whatever, it is it is not freedom as we know it.

As for the rest of them Russia was not going to be liberating anyone and if Germany was really worried about the Russians then first it should have made up with Britain and France and secondly, it should have waited to be attacked.

And then we’re left with Austria and Serbia. It’s difficult to pick a libertarian winner but my money’s on Austria. On the plus side it’s got waltzes, schnitzels, fancy uniforms and Ludwig von Mises. On the down side it’s just closed down the Bohemian Parliament. As for Serbia, the Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 as with the 1990s had seen their fair share of ethnic cleansing but on the plus side in July 1914 they were holding an apparently free and fair election.

I have recently been suffering from one of those annoying state-of-the-art flu bugs that made me properly ill for only a few days, but which then hasn’t allowed me to get truly better for another month. I still await full functionality.

When in such a state, I find serious writing difficult. (I can still manage unserious writing.) But what I really like to do when thus semi-incapacitated, is to read. And there is nothing, I find, like reading well-written history about long-ago times to make me count my modern blessings and cheer me up.

I recently began what looks like being a very good book about King Edward I. (A short excerpt from this book, on the subject of medieval historical evidence, can be read here.) Edward I was the English monarch who won the Battle of Crécy, and who soon after that presided – if that’s the right word – over the Black Death. You want a bug? That was a bug.

But I haven’t got to the Black Death bits yet. …

(LATER: And I won’t ever. I’m muddling Edward I up with Edward III, see commenter number one below, to whom thanks, and with apologies to everyone else. Edward III was the victor of Crécy, and I will wait in vain for anything about the Black Death in this book. I will be learning about such persons as Simon de Montfort. But the Black Death was, as I have read elsewhere, very nasty.)

… In the bits I have read so far, Edward is still a teenager, and his dad, Henry III, is fretting about how to crush a rebellion in his French possessions, and in particular (p. 16), how to persuade his English subjects to foot the bill for that enterprise:

The obvious solution was to impose a general levy on everyone – a tax – and Henry’s immediate predecessors had on occasion done just that. King Richard and King John had found that they could raise huge sums in this way – England, it bears repeating, was a rich and prosperous country – but such taxes proved highly unpopular, …

It is always worth keeping an eye out for a use of the word “but” when it would make more sense to have encountered the word “and”, or “therefore”. The unpopularity of taxes in England on the one hand, and on the other, the fact that England was a rich and prosperous country sound to me a lot like a cause and an effect. But the way that modern-day author Marc Morris phrases it, if your country is rich, it can accordingly afford to pay higher taxes without its richness being in any way disturbed.

It was this next bit that made me laugh out loud:

… but such taxes proved highly unpopular, and were regarded as tantamount to robbery.

Ah those medieval fools, so lacking in our modern grasp of the obvious and fundamental differences between taxes and robbery!

Here is a way in which things – things that in general are so much better now than then – have actually got worse.

I do not want to single out Marc Morris for criticism here. He is only describing matters in a way that most of his readers will immediately understand. Taxation? Of course. What he personally thinks about the idea of there now being higher taxes, to pay for such things as foreign wars, now, I do not know. As for me, although I will not live to see it, I look forward to a time when both taxation and death (at the sort of age that I will in due course be encountering it) are thought of in the same kind of way that we now think only of such things as the Black Death.

How on earth could those blundering and miserable twenty-first centurions not understand such obvious ideas?

[This is the text of a talk I gave on 20 March to the 6/20 Club in London. See also Part II and Part IV.]

I have heard that story with a few variations many times. And I find it deeply unsatisfying. The reason is because it doesn’t answer the fundamental question. Whose fault was it? Who was to blame?

Knowing more about the July Crisis doesn’t seem to help. What I have just outlined is a pretty short version. Christopher Clark’s version in his book Sleepwalkers stretches to over 600 pages with 100 pages of footnotes. University libraries groan with books on the subject. 25 years ago someone counted them all up and came up with a number of 25,000 books and pamphlets on the subject of the origins of the First World War. Seeing as this entire talk is based on books published since then one dreads to think what that number must be like now. There are even books on the history of the history. There is a lot of interesting detail. For instance, in the years leading up to the First World War something like 20 world leaders were assassinated. In most cases the perpetrator was an anarchist whom the authorities subsequently declared insane. You learn that Britain had a secret deal with France to protect the Channel in case of war; that in its declaration of war Germany made the entirely fictitious claim that France had bombed German cities; that the head of the Austrian counter-intelligence service was himself a Russian spy and that the French ambassador to London believed that French was the only language capable of “articulating rational thought”.

Perhaps more pertinently you learn that there is good evidence that the German government was planning for a war in 1914.

With most of the world colonised by Europeans who weren’t Germans, Germany hoped to be able to exercise influence over the declining Ottoman Empire. For instance a German general, Liman von Sanders had been sent out to take charge of the Turkish Army and there were plans to build a Berlin to Baghdad railway. They weren’t the only foreign advisers to Turkey. While a German was in charge of Turkey’s army, a Briton was in charge of its navy. Tellingly, the Hague Convention of 1912 called for a worldwide ban on opium. This eventually made its way into the Treaty of Versailles but in 1912 its opponents included Germany, Austria and Turkey.

Obviously, if Germany was to be able to exercise influence over Turkey it had to be able to get there. With hostility between Britain and Germany over Germany’s naval programme the only effective route lay through the Balkans. So, when Serbia massively increased its territory in the First Balkan War of 1912 Germany naturally grew disturbed.

On December 8 1912 a meeting was held with some of the major figures in the German government presided over by the Kaiser, Willhelm II. This has been dubbed a “War Council”. Whether it was or not who knows but it is interesting what followed next. First, Germany more or less accepted that the naval arms race with Britain was over and that Britain had won. Second, Germany massively increased the size of its army. Third, a succession of articles appeared in the press claiming that Russian military expansion was proceeding so quickly that by 1917 Germany could not hope to win a war. It is worth pointing out that the General Staff sincerely believed this. Fourth, the expansion of the Kiel Canal to allow battleships to sail between the North Sea and the Baltic was completed in 1914.

At about the same time General Bernhardi published his book Germany and the Next War. In it he essentially argued that might was right and that Germany should have not qualms about observing, for instance, international treaties. The book did especially well in Britain.

So, all this seems fairly clear cut until you learn that France and Russia were also pretty keen on war at the same time and made no efforts to diffuse the crisis that arose after Sarajevo. Indeed, Britain found itself in the uncomfortable position of not being able to deter Germany without simultaneously encouraging France and Russia.

The fact remains that after a hundred years there is still no consensus on who or what was to blame.

There are other mysteries. Explaining the Second World War is easy. You have a bad guy with bad ideas who started a war of conquest. But you look in vain for such a character in 1914.

Sure, the German government of the time has to bear a lot of the responsibility for the war but Kaiser Wilhelm is no Adolf Hitler. He was not a man espousing a foam-flecked, hate-filled, land-grabbing ideology. Sure, he had his moments but he quickly backed down and had a reputation for so doing. Similarly, the Tsar was no Stalin. He may have done stupid things like banning vodka and banning Jews from the boards of public companies but he wasn’t in the business of killing hundreds of thousands of people. Having said that it should be borne in mind that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, eagerly taken up by anti-semites around the world, was a Tsarist fabrication.

The truth is that the statesmen of Europe were acting rationally in the pursuit of limited objectives. Most of them were well aware of the likely consequences of a war. We can tell this in the hemming and hawing displayed by both the Russians and the Germans. Both Asquith, the British Prime Minister, and Churchill described the prospect of war as “Armageddon”. And yet despite this the disaster still managed to unfold. I tend to refer to this as the Michael Jennings question. How could such a disaster have happened when none of the leaders appear to have been particularly bellicose?

The conundrum gets worse. By November 1914, Germany had to all intents and purposes lost the war. The Schlieffen Plan had failed and they had been held at the Marne. Austria had suffered even worse disasters in Serbia and Galicia. So, why did it take them another 4 years to make peace?

From the Daily Mail:

Polish prince challenges Nigel Farage to a DUEL with swords over Ukip slurs on immigrants

And why not? Resort to the field of honour would be in accordance with prime ministerial precedent. Those were the days. The Sussex Advertiser of 23rd March 1829 blandly recorded, “His Grace was seen riding through the Horse-Guards at six o’clock on Saturday morning, and returned to Downing-street at eight.”

[This is the text of a talk I gave on 20 March to the 6/20 Club in London. See also Part I and Part III.]

So, what caused this catastrophe? If any of you are unfamiliar with the story it might be an idea to get out your smart phones out and pull up a map of Europe in 1914. When you do so you will notice that although western Europe is much the same as it is today, central Europe is completely different. There are far fewer borders and a country called Austria-Hungary occupies a large part of it.

As most of you will know on 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austrian throne was assassinated in Sarajevo the capital of Bosnia which he was visiting while inspecting army manoeuvres. Bosnia at the time was a recently-acquired part of the Austrian Empire having been formally incorporated in 1908. Although the Austrians didn’t know this at the time – though they certainly suspected it – Gavrilo Princip, the assassin, and his accomplices had been armed and trained by Serbia’s rogue intelligence service. I say “rogue” because the official Serbian government seems to have had little control over the service run by one Colonel Apis. Apis, as it happens, was executed by the Serbian government in exile in Greece in 1917 and there’s a definite suspicion that old scores were being settled.

Oddly enough, the Austrians weren’t that bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the man. Apart from his family no one seems to have liked him much. His funeral was distinctly low key although there was a rather touching display by about a 100 nobles who broke ranks to follow the coffin on its way to the station. More importantly, Franz Ferdinand was one of the few doves in a sea of hawks. Most of the Austrian hierarchy wanted war with Serbia. Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Chief of Staff had advocated war with Serbia over 20 times. Franz Ferdinand did not want war with Serbia. He felt that Slav nationalism was something that had to be accepted and the only way of doing this was to give Slavs a similar status to that Hungary had obtained in 1867. So his death changed the balance of power in Vienna. Much as the hierarchy were not bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the man, they were bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the symbol – the symbol of Austria’s monarchy and Empire, that is. The Serbs wanted to unite all the South Slavs: that is Slovenes, Croatians, Bosnians, Montenegrins and Macedonians in one state. However, most of these peoples lived in Austria. Now, if the South Slavs left there was no reason to think that the Czechs, Poles, Ruthenes or Romanians who were also part of the Austrian Empire would want to stay. Therefore, it was clear that Serbia’s ambitions posed an existential threat to Austria (correctly as it turned out). The solution? crush Serbia. And now the Austrians had a pretext.

Unfortunately (for the Austrians), Serbia had an ally: Russia. Russia regarded itself as the protector of the Slavs and Serbia in particular. But Austria also had an ally: Germany. Germany had spent the previous 20 years antagonising Britain, France and Russia and so was glad to have any ally at all. The fact that Austrians spoke German at a time when racial ideas were gaining ground was also a factor. But Russia itself had an ally: France. This was something of a marriage of convenience given that France was a democratic republic and Russia was an autocracy. But allies they were. All this meant that if Austria went to war with Serbia, Germany could find herself at war with France and both Austria and Germany could find themselves at war with Russia.

→ Continue reading: What caused the First World War? Part II – The July Crisis

[This is the text of a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago to the 6/20 Club in London. As you will see this introductory part is mainly about 1915. Part II is here]

By March 1915 the people of the United Kingdom were beginning to realise that the war was going to be much longer, involve many more men and be more expensive than they had previously imagined.

The military correspondent of the Times was a man called Charles à Court Repington. He was normally pretty astute. In a recent article he had argued that the war on the Western Front had become an attritional struggle. As there was a line of trenches stretching from Switzerland to the English Channel, there were no flanks to turn and no prospect of a war of manoeuvre. The two sides were of roughly equal quality. It had become a war where progress could only be made by material means: by being able to put more guns, shells, bullets and men on the battlefield than the enemy.

This massively favoured the Allies: France, Britain, Russia and Belgium. Combined they had more people and more industry than the Central Powers. They were also less good at “cleverness” in warfare – so a material struggle also played into their hands. Their victory was inevitable. But that didn’t mean it was going to come soon.

But at the time, the British in particular, were short of everything. This would come to a head soon afterwards when Repington, again, claimed that the Battle of Neuve Chapelle could have gone much better had the British had enough shells. This would lead almost immediately to the creation of the Ministry of Munitions under Lloyd George.

By this time food prices were beginning to rise. Some foods were already up by 50%. Given that a large proportion of the average person’s income went on food this was inevitably causing hardship. Worse still, this rise took place before the Germans declared the waters around the UK a warzone. I must confess I don’t entirely understand the ins and outs of this but essentially this means that submarines could sink shipping without warning. The upshot was that rationing would be introduced later in the war.

Government control also came to pubs with restricted opening hours. It would even become illegal to buy a round.

So far the Royal Navy had not had a good war. It had let the German battle cruiser Goeben slip through its fingers in the Mediterranean and into Constantinople where it became part of the Ottoman navy which attacked Russia. An entire squadron was destroyed off the coast of Chile and even the victories were hollow. At the Battle of Dogger Bank the chance to destroy a squadron of German battle cruisers was lost due to a signalling error.

But the man at the top, one Winston Churchill, was undeterred. He thought the Navy could take the Dardanelles, take Constantinople and knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war alone. Repington thought – or at least, I think he thought – that this was nonsense.

The Navy had, at least, for the time being deterred the German Navy from shelling any more coastal towns. Now the threat came from the Zeppelins high above.

The Army, traditionally the junior service, was having a much better war. But The Times still records about a hundred deaths a day and this at a quiet time when the Army in the field was still small. This was not going to last long. About 2 million men had volunteered and the job of turning them into useful soldiers had started.

Mind you, every cloud has a silver lining. Perhaps, given events earlier, that should be every eclipse has a corona. In July 1914 Ireland was on the verge of civil war. The First World War came along in the nick of time and for the duration of the war the main participants had agreed to bury the hatchet. Similarly, the suffragettes called off their campaign of destruction and there are far fewer strikes – Britain having been plagued by them in the years leading up to the war.

But as we know things were only going to get worse. In all the war lasted four years, killed 10 million people and saw the birth of a totalitarian communist regime. Something like 5 million Britons served on the Western Front. There they experienced trenches, mud, barbed wire and shelling at a minimum. Others would have experienced gas, machine-gun fire and going “over the top”. A million never came back. And for what? Twenty years of political instability followed by the experience of having to do it all over again in the Second World War.

In Britain we tend to think of the First World War as being worse than the Second. This is because, almost uniquely amongst the participants, British losses in the First World War were worse. It is also worth bearing in mind that Britain’s losses in the First World War were much lower than everyone else’s. France lost a million and a half, Germany 2 million. Russia’s losses are anyone’s guess. For all the talk of tragedy and futility, the truth is that Britain got off lightly.

For many libertarians the First World War is particularly tragic. They tend to think (not entirely correctly) of the period before it as a libertarian golden age. While there was plenty of state violence to go around, there were much lower taxes, far fewer planning regulations, few nationalised industries, truly private railways and individuals were allowed to own firearms. If you were in the mood for smoking some opium you needed only to wander down to the nearest chemist.

The Times 8 March 1915 p8

What is a military correspondent to do when in the course of wartime his government is doing something sensible? Why, support it of course. But what if that government is doing something very, very stupid like launching the Gallipoli campaign? The answer, of course, is to support that too – in wartime loyalty trumps honesty – but point out the difficulties.

Which is precisely what Charles à Court Repington, Military Correspondent of The Times, does. In some detail.

The reasons in favour of this operation are overwhelming, provided that the risks and necessary preparations have been coolly calculated in advance, and such naval and military force as may be allotted to the object in view can be spared from the decisive theatre of war.

Note the use of the word “decisive”. The meaning is clear: the Western Front is decisive, this isn’t.

The defences of the Dardanelles are formidable, and nothing is gained by denying the fact. The Straits are narrow, the channels are winding and they are mined. A considerable current runs down the Straits, and the ground on both sides offers excellent sites for batteries both high and low, and for guns giving high-angle fire for the attack on ships’ decks.

The best way to attack the Dardanelles is by means of a conjoint naval and military expedition,…

Which they’re not doing… yet. By the way, I was once told that strictly speaking the word “military” refers exclusively to land-based warfare. I think this is how the word is being used here.

… and a purely naval attack can only be justified if the necessary and very large military force cannot be spared,…

Which it can’t, not least because it doesn’t exist.

… or if our information is so good,

Which it isn’t.

…and the chances have been so carefully weighed, that the success of a naval attack is reasonably probable.

But hey…

…if they can master these formidable Straits, and appear before the walls of Constantinople they will have accomplished a feat of arms which will live in the history of the world.

He’s not kidding.

And whose bright idea is this campaign? Why, Winston Churchill, of course. If you want a way of thinking about Churchill prior to “We’ll fight them on the beaches” and all that, think Tigger from the Winnie-the-Pooh books – loud, abrasive, energetic, enthusiastic, convinced of his genius and indispensability, hare-brained. Such an attitude has already caused problems but now it will cause the sort of problems that cannot be ignored. Ultimately, it will lead to Churchill’s removal from government and a stint in the trenches. It is not something that will ever be entirely forgotten. Indeed one wonders if Churchill timed his death in January 1965 to avoid the 50th anniversary of Gallipoli in the February.

About the best that can be said for Gallipoli is what would they have said had it never been tried? There would doubtless have been people claiming that here was a scheme that would have won the war much more quickly at far less cost and it was only a lack of imagination and institutional stubbornness that prevented it being pursued.

The Times 22 February 1915 p6

Many of you will have noticed that I haven’t been blogging from a hundred years ago as much as I used to. This is mainly because my source material, The Times, isn’t what it used to be. It is much shorter – 16 pages instead of 24 – and much less accurate. In wartime you do not and often cannot know what is going on.

Here, however, we do have an accurate report, from the front line no less:

…it may interest your correspondent to know that we were served out with grease before going up to the trenches on Christmas Eve. I rubbed my legs and feet thoroughly with this and was careful to leave my boots and puttees loose – but I arrived home on January 1 with frostbite in both feet, and am still laid up.

He goes on:

…I was for 36 hours in a trench which was so badly knocked about and fallen in, and had such an ineffective parapet, that it was simply “asking for trouble” to stand in anything like an upright position. The main trench was over knee deep in liquid mud.

Before getting indulging in some light sarcasm:

Our cubby-hole, by the way, had fallen in, and we had no hot shower-baths, stoves, drawing room carpets, or other luxuries which abound in these Aladdin’s-Cave-cum-Ritz-Hotel trenches I have read about in the papers.

The thing that really strikes me about this letter is that it pulls no punches. I have often heard it said that the people at home had no idea what life was like at the front. But if letters like this were getting published on a daily basis I wonder if that’s really true.

The Times 25 January 1915 p9

I just came across this tour de force of a speech by Dan Hannan at the Oxford Union, courtesy of David Thompson. Thank goodness for YouTube.

I particularly like the bit at the end, where Hannan shows that he knows more about the Levellers than do those arguing against him. “Proto-libertarians” is a very good description of just what kind of libertarians the Levellers were. They certainly weren’t socialists.

Just over thirteen minutes in length. Lots of good points made in a very short time, despite interruptions from the floor. No wonder Hannan’s debating opponents looked so scowly and unhappy, as Thompson notes.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|