We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

“America’s militant agnostic minority has totally distorted the meaning of separation of church and state. It doesn’t mean banning religion and religious values from the public square. It doesn’t mean Howard Stern’s off-color (and frequently off-the-wall) ‘humor’ is protected speech, while the free _expression of religion is banned. It means the United States will establish no official religion, while remaining equally hospitable to all religions — and to those who practice none. Religious principle is not something to fear and loathe and banish from the public square; it is a code of conduct on which we can and should rely to guide our personal and civic behavior”

– singer Pat Boone, writing in the San Diego Union-Tribune.

I know, I know – Pat Boone? But he seems to me he got this one about right (except for the implication that Howard Stern’s humor may not be protected speech).

Contrary to popular belief, “separation of church and state” is not found in the US Constitution. What is found in the Constitution is a prohibition on the establishment of a state church (which is why it is known as the Establishment Clause) reading thusly “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion…” The ‘separation’ meme comes from correspondence between Jefferson and Madison, but was never enacted in Constitutional language.

A nice, fairly even-handed intro can be found here.

Personally, I think that the issue of impending theocracy and separation of church and state evaporates, once you take seriously the US Constitution’s limited grant of power to the national government. If the national government is held to its enumerated powers, then it lacks the power to implement into civil law most behavioral controls that various religions might promote. Since the federal government restricted to its enumerated powers has no Constitutional basis to, for example, ban abortions, it simply cannot be used for that purpose by the purported theocrats among us.

The various left-wing ninnies who are running around bleating about theocracy are, in effect, hoist on their own petard. Having spent generations destroying the idea of limited government and creating an all-powerful national state, it ill becomes them to complain now that their tool is being turned to different ends. Even so, it is astonishing that virtually none of them realize that the uses to which the Republicans want to put federal power are inevitable, once you establish an all-powerful state in a country that is actually quite Christian and conservative, all told. It is sad but unsurprising that none of them are willing to attack the problem at its root by calling for limited government. No, the only solution the statists can imagine is seizing power again, themselves.

It will come as no surprise to regular readers of this blog that we have long regarded the Ban on Foxhunting with Dogs as having very little to do with foxhunting.

As David Carr has pointed out before, those who shout loudly that the move against hunting is ‘undemocratic’ are completely wrong: it is perfectly democratic. Welcome to the world in which there is no give and take of civil society… welcome to the world of total politics.

Mr Bradley says: ‘We ought at last to own up to it: the struggle over the Bill was not just about animal welfare and personal freedom: it was class war.’

The MP for The Wrekin adds that it was the ‘toffs’ who declared war on Labour by resisting the ban, but agrees that both sides are battling for power, not animal welfare.

‘This was not about the politics of envy but the polities of power. Ultimately it’s about who governs Britain.’

[…]

‘Labour governments have come and gone and left little impression on the gentry. But a ban on hunting touches them. It threatens their inalienable right to do as they please on their own land. For the first time, a decision of a Parliament they don’t control has breached their wrought-iron gates.

No kidding. That is what we have been pointing out here on Samizdata.net for quite some time and why we have treated commenters who shrugged and said “why get worked up about foxhunting?” with such derision. It was never about hunting but rather things that are far, far more fundamental. It is about those who would make all things subject to democratically sanctified politics (‘Rule by Activist’) seeking to crush those who see private property and society, rather than state, as what matters.

Mr Bradley, 51, admits that he personally sees the campaign to save hunting as an assault on his right to govern as a Labour MP.

And Mr. Bradley is correct but for one thing: the battle in question is about the limits of political power and not just Labour’s political power. Until the supporter of the Countryside Alliance see that they are actually struggling against the idea of a total political state, they will not even be fighting the right war. It is not about who controls the political system but what the political system is permitted to do under anyone’s control. The United States has a system of separation of powers and constitutional governance which (at least in theory even though not in fact) places whole areas of civil society outside politics. Britain on the other hand has no such well defined system and the customary checks and balances have been all but swept away under the current regime. Britain’s ‘unwritten constitution’ has been shown to be a paper tiger.

But those who look to the Tories to save them from the class warriors of the left are missing another fundamental truth. During their time in power, the Tory Party set the very foundations upon which Blair and Blunkett are building the apparatus for totally replacing social processes with political processes, a world in which nothing cannot be compelled by law if that is what ‘The People’ want: populist authoritarianism has been here for a while but now it no longer even feels it has to hide its true face behind a mask.

Moreover it would take another blind man to look back on Michael Howard’s time as Home Secretary and see him as being less corrosive to civil liberties that the monstrous David Blunkett. Have you heard the outraged Tory opposition to the terrifying Civil Contingencies Act? Of course not, because the intellectual bankruptcy of the Tory party is now complete… for the most part they support it. If the so-called ‘Conservatives’ will not lift a finger to stop the destruction of the ancient underpinnings of British liberty, what exactly are they allegedly intending to ‘conserve’? The Tories are not part of the solution, they are part of the problem and the sooner the UKIP destroy them by making them permanently unelectable, the better, so that some sort of real opposition can fill the ideological vacuum.

Those who were marching against banning foxhunting completely miss the issues at stake here. The issue is not and never has been foxhunting but rather the acceptable limits of politics. And you cannot resolve that issue via the political system in Britain. It is only once the people who oppose the ban on foxhunting and the people who oppose the Civil Contingencies Act and the people who oppose the introduction of ID cards and data pooling all realise that these are NOT separate issues but the same issue will effective opposition be possible. And I fear that opposition will, at least until the ‘facts on the ground’ can be established, have to be via civil disobedience and other ways to make sections of this country ungovernable by whatever means prove effective. The solution does not lie in ‘democracy’ but rather by enough people across the country asserting their right to free association and non-politically mediated social interaction by refusing to obey the entirely democratic laws which come out of Westminster.

Peter Bradley is right and he has provided any who are paying attention with a moment of utter clarity: It is time to challenge his right to ‘rule’ by whatever means necessary.

This article from the Washington Post, on the application of the little known Data Quality Act to hobble the regulatory leviathan, is full of unintentional insights. The Data Quality Act is, well, let the Post tell it, and let the insights begin!

The Data Quality Act — written by an industry lobbyist and slipped into a giant appropriations bill in 2000 without congressional discussion or debate — is just two sentences directing the OMB to ensure that all information disseminated by the federal government is reliable.

The first insight is, of course, the clonking great pro-government, pro-regulation bias that the Post brings to this story. Note the disparaging terms applied to this piece of legislation, which has a genesis and a pedigree that is totally ordinary – most legislation is the product of interested parties, and most finds its way onto the books via massive omnibus bills that no one reads. However, these routine facts of Washington life are given ominous prominence only when the media outlet is opposed to whatever was done. The rest of the story is riddled with similar bias – in the Post’s world, regulation is always good, always to protect the people, never fails a cost-benefit test, always supported by the preponderance of the scientific evidence, etc.

The next set of unintentional insights comes to us when the relatively innocuous purpose of the Act collides with the prerogatives of the regulatory state.

But many consumers, conservationists and worker advocates say the act is inherently biased in favor of industry. By demanding that government use only data that have achieved a rare level of certainty, these critics maintain, the act dismisses scientific information that in the past would have triggered tighter regulation.

First, of course, note who the Post asks for their opinion. Of equal interest is the rather revealing admission that, in the past, regulation was apparently handed down on the basis of information that was, how to put this, of less than adequate quality. Declining to regulate because the data isn’t there is, of course, a Bad Thing.

These final comments surely need no elaboration.

“It’s a tool to clobber every effort to regulate,” said Rena Steinzor, a professor of law and director of the Environmental Law Clinic at the University of Maryland. “In my view, it amounts to censorship and harassment.”

. . . .

Yet Steinzor, the Maryland environmental lawyer, and other critics complain that the OMB’s involvement politicizes the process. The expertise of the handful of scientists hired by Graham, they say, cannot match that of the thousands of experts on agency staffs.

Compared to other people (or rather, other people of my acquaintance) I joined the internet revolution rather late. While most people I meet are able to boast that they have had an e-mail address since the late (or even mid) 1980’s, I was not similarly endowed until 1998.

But what I lacked in early adoption techniques I made up for in subsequent enthusiasm. This was a whole new frontier and I revelled and rejoiced in the exhilirating liberation it provided. I am sure that plenty of our readers have experienced that same feeling.

And it was while I was on this big journey of discovery and emancipation that I stumbled across a forum (there were no blogs in those olden times) run by LM Magazine. LM stands (or stood) for ‘Living Marxism’ and it was run by the same people who, today, run Spiked-Online.

As with most internet fora, there was a regular contingent of posters and, in the case of the LM Forum, this consisted of a whole gaggle of Marxists, Communists and Trotskyites. Into this lion’s den barged (or perhaps blundered) two libertarians; one of them was me and the other was an American called Ed Collins. → Continue reading: My friend Ed

Almost anything you say about how ideas spread and eventually get accepted and acted upon is liable to be (a) true, but (b) over-simplified, because the whole truth about how ideas spread and get acted upon is far, far too complicated ever to keep complete track of. Where the definite falsehood creeps in is when people say, or more commonly imply through the other things that they say, that ideas can only spread in this way or that way, and that all the other ways they can spread don’t count for anything.

There is one such implied falsehood which we at Samizdata, for humiliatingly obvious reasons, are likely to be particularly interested in and cheered up by contesting. This is the idea that what matters when it comes to spreading ideas is sheer weight of numbers. It’s the idea that getting some other idea to catch on and be acted upon is a question of assembling a sufficiently huge number of people who believe this idea to be true or good or appealing, and then for this vast throng of supporting people to prevail against the other almost equally vast (but not quite) throng of people who believe the opposite.

Clearly, as a partial description about how some ideas spread, at some times and in some places, this kind of thing can definitely happen. Political elections are often just like this. This vast throng of humanity votes for this idea, that throng votes for that idea, and the winners are the ones who appeal to the biggest throng.

But as a complete description of how ideas spread this picture is false. Most things, after all, are not decided by political elections. For example, I would say that when historians look back on our era, they will say that the development of the Internet was a huge historical event, up there with the first printed bibles in local languages, or with the development of the railways or of the motor car. Yet neither the internet, nor printing, nor railways, nor motor cars were any of them set in motion merely by political electorates, and nor, once they had got underway, were any political electorates ever invited to vote against them.

The weight-of-numbers model is even seriously false when it comes to understanding the full story of most political elections. Yes, elections decide who will occupy various political offices, and what will be written about in newspaper editorials for the next few years. But these elections seldom decide very much about what actually gets done from these offices. Instead, democratic true believers (the ones who really do believe that absolutely everything should be decided with a head count) constantly rage at how “undemocratic” democracy typically turns out to be. They have a point.

I will now offer you a thought experiment, the point of which is to explain how unimportant mere numbers of believers in an idea can be, and how much more interesting and complicated the spread of and adoption of ideas can sometimes be. → Continue reading: How ideas spread and get acted on – the weight of numbers fallacy

There’s an article in today’s New York Times, an article about another article, in Homes & Gardens. But follow that Homes & Gardens link and you won’t find any mention of this article, because it was published in 1938 and was about Adolf Hitler’s “Bavarian retreat”.

The predominant color scheme of Hitler’s “bright, airy chalet” was “a light jade green.” Chairs and tables of braided cane graced the sun parlor, and the Führer, “a droll raconteur,” decorated his entrance hall with “cactus plants in majolica pots.”

Such are the precious and chilling observations in an irony-free 1938 article in Homes & Gardens, a British magazine, on Hitler’s mountain retreat in the Bavarian Alps. A bit of arcana, to be sure, but one that has dropped squarely into the current debate over the Internet and intellectual property. This file, too, is being shared.

The resurrection of the article can be traced to Simon Waldman, the director of digital publishing at Guardian Newspapers in Britain, who says he was given a vintage issue of the magazine by his father-in-law. Noticing the Hitler spread, which doted on the compound’s high-mountain beauty (“the fairest view in all Europe”) at a time when the Nazis had already gobbled up Austria, Mr. Waldman scanned the three pages and posted them on his personal Web site last May. They sat largely unnoticed until about three weeks ago, when Mr. Waldman made them more prominent on his site and sent an e-mail message to the current editor of Homes & Gardens, Isobel McKenzie-Price, pointing up the article as a historical curiosity.

Ms. McKenzie-Price, citing copyright rules, politely requested that he remove the pages. Mr. Waldman did so, but not before other Web users had turned the pages into communal property, like so many songs and photographs and movies and words that have been illegally traded for more than a decade in the Internet’s back alleys.

Still, there was a question of whether the magazine’s position was a stance against property theft or a bit of red-faced persnicketiness.

Now this episode could be turned into yet another intellectual property comment fest, and if that’s what people want, fine, go ahead. But what interests me is the ineptness of the commercial Homes & Gardens response, their woeful neglect of a major business opportunity. An honest response from them about their reluctance to get involved in political judgements of the many and varied political people whose houses they have featured in their pages over the decades, and about all the other famous (and infamous) people whose homes they’ve written about over the years, together with a website pointing us all to their archives, might surely have served their commercial purposes far better, I would have thought.

This might have morphed into a discussion of the comparably fabulous pads occupied by other famous monster-criminal-dictators (including some featured in Homes & Gardens, of the exact degree of opulence/disgustingness of the homes of the Russian and Chinese Communist apparatchiks, but of their far greater reluctance (when compared to openly inegalitarian despots like Hitler) to reveal their living arrangements to the world, in the pages of such publications as Homes & Gardens. There might also have been some quite admiring further thoughts on the nice way that Hitler had arranged matters for himself, from the domestic point of view, the way the design of the house made maximum use of the view of the mountains, etc., etc. It does sound like a really nice place.

Such a discussion could surely have been combined with a robust defence by Homes & Gardens of their intellectual property rights under existing law, and in a way that might have been to their further commercial advantage. They might have simply reprinted the entire piece in a current issue, together with their current comments about it.

But no. Down go the shutters. And an opportunity to bring Homes & Gardens to the non-contemptuous attention of a whole new generation of readers, instead of to its contemptuous attention, is missed. Or is about to be missed. → Continue reading: Hitler’s home in Homes & Gardens

One of the more annoying things about modern large bookshops is that they divide the non-fiction books into a vast number of over-defined categories. This is not a huge difficulty if you are looking for a cookbook, or a book about trains, or a travel guidebook, as it is pretty clear what sections those books belong in. However, when we get to the social sciences things get hazy. If I am looking for (say) one of Ian Buruma‘s books on Asia (which are all worth a read, by the way), it is impossible to know whether the book in question will be on the shelves in “Asian History”, “Eastern culture”, “Travel writing”, “Sociology”, “Chinese History”, or one several other categories, even though if you look at all his books together they are clearly all have a very similar theme. It just does not fit into bookshop categorisation.

This is fine if you are looking for a particular book. You just ask at the information counter, they look it up in the computer and they tell you where it is and whether they have any copies. However, if you are trying to find it without help it can be close to impossible.

In any event, when I was wandering through my local branch of Books etc the other day, I found myself walking past a section I hadn’t noticed before, labelled “anti-globalisation”. That’s right, they had a section devoted to the works of Michael Moore, Noam Chomksy and the like. People who wanted to read such books can go straight to that section without having to be exposed to anything else. I’m sure they find this very convenient.

Even better, the bookshop encourages its staff to recommend books to customers. They even go to the trouble of giving their staff members little cards on which they can write down their recommendations and attach them to the shelves in the store. This is a good practice, as it may help readers find books and it also makes it clear that the booksellers are people who like to read themselves. But, even so, I had personal issues with the anti-globalisation recommendations.

Ugh.

Save me.

Seriously, I suspect that the number of people who have read Michael Moore and are not already aware of the existence of John Pilger and Noam Chomsky already is small (or perhaps I overestimate them). I think recommendations like this are better when they refer people who have read something well known to something that is both rather more obscure and also good. And Pilger and Chomsky are not especially obscure, however much I might wish it were so.

However, in the chance that there might be anyone walking through the bookshop who might have discovered Michael Moore but not Pilger or Chomsky, I thought I had a duty to save them from this (and also there was a Samizdata post in it). Therefore, although it was a bit naughty of me I removed the little cards from the shelf and walked out with them. (Yes, okay, technically I stole them. However, sometimes the ends do justify the means).

As I was walking out of the shop, it struck me that it would be kind of cool to get a few of the blank cards, write out a few book recommendations of my own, and then attach them to the shelves. However, when I thought about it some more, I realised I didn’t need anyone to supply me with a stock of blank cards. For I have the miracles of modern technology at my disposal, and I could produce some of my own. I could go back into the bookshop and leave something like this.

Or perhaps this.

The fun could be never ending. → Continue reading: Globalisation, bookshops, and the Anglosphere

Whilst perusing Harry’s Place, I discovered a reference to an essay written by Labour MP Peter Hain in 2000 about ‘libertarian socialism’ over on the Chartist website called Rediscovering our libertarian roots.

The whole notion of this alleged form of libertarianism is something I have commented on before, but I have probably never seen a more clearly written explanation of the true thinking that underpins ‘libertarian socialism’ than this article by Hain.

It is very important to understand what Hain’s essay is and is not. It is not a philosophical paper making logical links between socialism and libertarianism. What it is is a tactical paper very much along the lines of the one I wrote called Giving libertarianism a left hook, only with the opposite objective.

Rather than fisking Hain’s article, I will just quote what I think are the most illustrative sections (emphasis added):

The key elements of libertarian socialism – decentralisation, democracy, popular sovereignty and a refusal to accept that collectivism means subjugating individual liberty.

[…]

Discredited by its association with statism, socialism’s rehabilitation can only be achieved through a recovery of its libertarian roots, applying these to the modern age through Labour’s Third Way.

[…]

Underlying libertarian socialism is a different and distinct notion of politics which rests on the belief that it is only through interaction with others in political activity and civic action that individuals will fully realise their humanity. Democracy should therefore extend not simply to government but throughout society: in industry, in the neighbourhood or in any arrangement by which people organise their lives.

[…]

However, power can only be spread downwards in an equitable manner if there is a national framework where opportunities, resources, wealth and income are distributed fairly, where democratic rights are constitutionally entrenched, and where there is equal sexual and racial opportunity. This is where socialism becomes the essential counterpart to libertarianism which could otherwise, and indeed sometimes is, right wing. It means nationally established minimum levels of public provision, such as for housing, public transport, social services, day-care facilities, home helps and so on. The extent to which these are ‘topped up’ and different priorities set between them, is then a matter for local decision.

[…]

Most individuals need active government to intervene and curb market excess and distortions of market power. For choice and individual aspiration to be real for the many, and not simply for the privileged few, people must have the power to choose.

Nevertheless the old left nostrum that markets equal capitalism and the absence of markets equals socialism, is utterly simplistic. As Aneurin Bevan argued, the extent to which markets are regulated or subjected to strategic intervention by government is not a matter of theoretical dogma, but a practical matter to be judged on its merit. That is why a Third Way Labour government is not passive, but highly active, working in partnership with business and investing in the skills and modern infrastructure which market forces and the private sector do not provide

There are so many problems and manifest contradictions that leap off the page it is difficult to know where to start. The core of what makes this so wrong lies as usual at the meta-contextual level. The problem is one of the distorting lens of the writer’s world view, based as they clearly are on utterly utilitarian principles. Hain says libertarian socialists are characterised by a “refusal to accept that collectivism means subjugating individual liberty”, whereupon he follows with an article which lists the many ways in which his socialist system would in fact do precisely that.

The core of Hain’s view is that politics, which is a euphemism for ‘the struggle for control of the means of collective coercion’, is the essential core around which ‘society’ exists and interacts. Thus when he says society must be ‘completely democratic’, he means society must be completely political (based upon collective coercion). Yet the argument that it is only by this that individual liberty can be realised falls at the first fence by virtue of the fact you cannot opt out of a political society and particularly a democratic political society: if my neighbour gets to vote on all aspects of “any arrangement by which people organise their lives”, then clearly my individual wish regarding what I may do with my own life is by no means my choice unless that choice is quite literally a popular one.

Secondly, if democratic rights are to be ‘constitutionally enshrined’ and the society is completely democratic in all its aspects and therefore completely political, then how can the individual rights of people be insulated from the democratic political process which may seek to abridge them? You can either have complete democracy enshrined or, as the American founding fathers tried with limited success, you can have individual rights enshrined and placed outside the reach of democratic politics, but you cannot logically have both.

The notion that a completely politicized democratic ‘society’ of the kind advocated by Hain could by its very nature allow any personal liberty whatsoever in a meaningful sense is manifestly absurd. If you cannot opt out of something you have not previously agreed to, in what manner are you free? If society is totally political, then you may have ‘permissions’ to do this or that, won by the give and take of democratic political processes but you do not have super-political inalienable rights at all. Politics can in theory make you ‘free from starving’ perhaps (in practise of course it tends to do the opposite), but what about being free to try or not try some course of action? When every aspect of life is subject to the views of a plurality of other people, there is no liberty to just try anything at all on your own initiative. What Hain is arguing for is by his own words collectivism.

It seems to me that one thing all forms of collectivism share is that individual choice is always subordinate to The Group, be it the fascist volk or a local soviet or an anarcho-syndicalist people’s council or whatever other fiction of ‘society’ the state decides to use. So talk of individual rights within the context of a collectivist ‘society’ is either incoherence or if not it is nothing more than a tactical ploy to conflate a violence based system of total governance with its antithesis in a manner well understood. As I wrote in a recent article, unlike a collectivist kibbutz, which is a voluntary collectivist commune, you cannot just walk out of the door of a collectivist ‘society’ and start setting up private arrangements with other willing people if the majority do not want you to do that: they will in fact deputise the use of violence to prevent it.

The logical flaws in the ‘collectivist society replacing collectivist state’ notion are so obvious that they have been pointed out a great many times by a great many people, but I will add my voice to the throng anyway. Hain, like Marx before him, clearly sees libertarian socialism as working towards the ‘withering away of the state’ as a true collectivist ‘society’ comes to replace it. But to maintain such a condition of total political governance will require the use of force to prevent any consensual but not democratically sanctioned acts between willing individuals. To maintain this suppression of spontaneous several relationships, a collectivist socialist ‘society’ must be organised and structured in certain ways that make it indistinguishable from a collectivist socialist state.

So if for a collectivist ‘society’ to function there must be a high degree of politically imposed non-spontaneous behaviour from its ‘citizens’ (such as preventing a person selling their own labour for less than the political community will allow them to), and those mandates must be backed with the threat of violence (i.e. law) if they are not to be ignored, then what we have a political State by any reasonable definition of the word ‘State’, much as Rousseau would have defined one. In fact, socialism must be the most ironic use of language in the history of human linguistics: it is the advocacy of the complete replacement of social interaction with political interaction, the very negation of civil society itself. ‘Politicalism’ would be a more honest term.

Now of course all societies have laws, be it polycentric law or state imposed law. Even the most libertarian society plausibly imaginable will have force backed prohibitions against the unjustified use of violence, which is to say (in very crude and simplified terms) libertarian law deals with ‘that which you may not do without consent of the person to or with whom you are doing it’. You may not cause me harm with dioxin from your factory because I have not given you leave to put your chemicals in my lungs. This law is based on the principle that the individual’s rights to his body (and property) are his own.

However the collectivist places the protection of the political collective as more important than the individual and thus collective law is whatever the political collective says it is. If the political collective says ‘a factory may not put dioxin in Fred’s lungs because we want a more environmentally safe place to live for all of us’, then that is the law because the political collective has said so, not because Fred has the right to control the contents of his own lungs.

But if they say ‘a factory may indeed put dioxin in Fred’s lungs because we want a better economy and more stuff for the rest of us’ then that too is the voice of the collective. And Fred? If he does not like it, well, it is “only through interaction with others in political activity and civic action that individuals will fully realise their humanity”. And if Fred finds himself in the minority? Now Fred has a problem because as the society is ‘totally democratic’, we will have none of this nonsense of independent and politically neutral courts stepping in to support the objective and several rights of Fred against the collective, as if that could happen in our libertarian socialist paradise, we would no longer have our totally democratic society.

So as Hain says it is only through trying to control the means of collective coercion, the means to use force to make people do things, that Fred can ‘fully realise his humanity’, how is this ‘libertarian socialism’ going to protect the individual called Fred’s rights? What if the majority in Hain’s total democracy don’t like Fred? And who will define these ‘individual’ rights? The political collective, of course. Forget constitutions which constrain democracy because those are anti-democratic (which is rather the point). Forget consensual several relationships because everything is democratic, meaning no politically unpopular relationships will be allowed. Forget custom and culture as a means to moderate interactions because that is not political. If Fred is not popular, Fred is just out of luck.

Fascist collectivists try to prevent mixed race sex, socialist collectivists try to prevent ‘undemocratic’ private trade, but the principle of collectivism is always the same. If an individual does something he wants to do in a collectivist ‘society’, it is because the political collective allows him to do it, not because it is his right to do as he pleases with those who are willing participants.

Clearly this democratic ‘society’ of Hain’s is willing to use force to prevent free trade between willing individuals unless they happen to be acting in a manner which is politically favoured. Much as most states currently use force to try and prevent free trade in drugs between willing individuals, the same will be done to any relationship the political collective dislikes. Put another way, this democratic society is in fact a state which will be organised to enforce the political will of the plurality on an epic scale, given that this would be a totally political society. And any time someone tries to opt out, they will quickly discover just how ‘withered away’ the state is under ‘socialist libertarianism’: not very.

Of course just as modern states may be more repressive or less repressive (running on a continuum from, say, Switzerland to North Korea), some implementations of so-called ‘socialist libertarianism’ may be more savage or less savage in their interpretation of an unfettered total political democracy at a given point in time. An individual who shares the views, aspirations and prejudices of the majority may well think that life seems equitable and good. After all, if he is allowed to do the things he wishes to do, why complain? But as the democracy advocated by Hain is total, what if he wants to do that which not popular?

I have long thought that supporters of collectivism (be it of the socialist, nationalist or conservative kind) who are homosexuals or who are people with other lifestyles that will never be popular (in the literal sense of the word, actually favoured by the majority) are unwise in the extreme to advocate anything that does not reserve rights to individuals before collectives. Socialism is by Hain’s own words seen as “…where socialism becomes the essential counterpart to libertarianism which could otherwise – and indeed sometimes is – right wing”. Of course by ‘right wing’ Hain means individualist. Libertarianism puts the rights of the individual as the first of all virtues. Libertarian socialism is individualist collectivism, ergo libertarian socialism is an oxymoron.

So what is Hain’s total political ‘society’ in reality? It is locally organised totalitarianism with Big Brother based in the local town hall rather than in Whitehall.

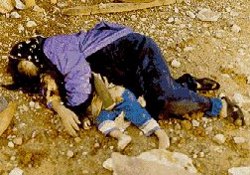

One of the news headlines today was about the discovery of mass grave in Mahawil area in Iraq. So far remains of more than 3,000 people have been found but Iraqis fear up to 15,000 people reported missing in the area may have been buried there during Saddam’s government crackdown on Shi’ites when they launched an uprising in 1991. Reuters reports:

Many families stood silently behind a ring of barbed wire coils separating them from the excavation in an attempt to preserve the site but others walked through the piles.

As an earthmover scraped heaps of rich brown earth from the site, bones protruded from the dirt. Once extricated, skulls and what look like the bones from the rest of the bodies were heaped into crumbled piles or stuffed into plastic bags. Clothing hung from the bones. Some skulls were cracked.

Since Saddam’s fall in the U.S.-led war on Iraq, mass graves have been unearthed in Najaf, Basra, Babylon and other areas and are still being found as Iraqis feel free to recount tales of arrests, torture and killings once too risky to tell.

To all those protesters whose righteous hatred for the United States and Britain was declared out of self-proclaimed desire for peace. Is this the kind of ‘peace’ you wanted to preserve when you cried “not in my name”?

Araya Hussein carried the remains of her husband in a bag away from the site weeping.

He went missing in 1991 when we had 10 children. I thought he was a prisoner and would one day come home. I never imagined I would be carrying his bones home.

Explain to this woman why your righteous wrath was directed at Bush and Blair but not at Saddam. Explain how according to your warped view of the world Saddam has ‘the right’ to rule Iraq and kill thousands without any fear of retribution. Explain how you can end up supporting an evil and oppressive regime and distance yourself from the long awaited liberation.

Damn you and your coddled, self-centered and twisted minds. You have caused enough misery and suffering by your irrational and irresponsible opposition to anything that might bring freedom to those parts of the world where free expression is an unknown concept. Perhaps you should change your slogans and cry for ‘peace of mind’, your minds that is, in the face of the gruesome truth emerging from Iraq.

The mass murders in Iraq have been stopped… but not in your name

If you oppose a war to overthrow Ba’athist Socialism in Iraq but also claim to despise Saddam Hussain, then I can only assume that you are a ‘containment’ advocate… which is to say you view the policy of the last 12 years which prevented the Iraqi regime attacking it neighbours as an adequate response. You probably also think that containing Hussain within Iraq’s borders is all that is really in the interests of any outsiders (which in practice means primarily the USA and UK)… therefore what happens inside Iraq is really not germane. You might even add that you would be quite happy to see the Iraqi people overthrow Hussain, just not with our tax money or the blood of US and UK soldiers, thanks.

Okay, I do not agree but that is indeed a coherent argument to make.

However if part of your argument against this impending war is ‘many Iraqi civilians will be killed and thus it is unjustified’, then you are not making the ‘containment’ argument, nor are you making a ‘not in our national interest’ argument. What you are saying is that the interests of the Iraqi people are actually important to you and presumably have some objective value.

So ponder this: Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist Socialist regime has been in power since 1979… about 22 years. Although the figures for how many people his regime has murdered varies hugely depending on the source and which axe they are grinding (with the high figure being 2 million), I will assume that the one million statistic being widely bandied about is correct… and lets for now just gloss over the number of people tortured, imprisoned or driven into exile.

That is approximately 45,500 Iraqi and Kurdish people per year murdered inside Iraq by the Ba’athist government… about 125 people per day that Saddam Hussein has been in power (or equal to about two Waco massacres every day). This is a crude blood calculus of course but it does put the Butcher’s Bill up where it can be seen and priced. Even if the number was half that, it gives us some measure of the scale of the horror involved.

So if your argument against a (hopefully short) war to overthrow Iraq’s Socialist regime is based on the undeniable fact innocent people will die, you would seem to be saying that it only matters when Iraqis are killed if outsiders are the ones killing them… because Iraqis are already dying at the hands of the Iraqi state in prodigious numbers. If that is indeed your position, I would contend that you really do not give a damn about what is best for the Iraqi people.

When the air turned to poison in Halabja: the reality of peace in Iraq

I have seen many good ideas put forth about why taking on Iraq is a good strategy, and how different approaches to the other members of the “axis of evil” are appropriate. I think there is something more profound happening in the Bush administration, a policy change whose outlines are now appearing and whose scope is breathtaking in its sweep.

Prior to 9/11, Bush was considered an isolationist. There were worries about America disengaging from the rest of the world. Folks, that is exactly where the endgame of the current global strategy is leading. President Bush and his advisors are cutting the Gordian knots which tie the US into permanent global deployment.

We’ve got large numbers of troops pinned down in the Middle East. Steven den Beste has already shown how the conquest of Iraq removes the reason for basing large numbers of forces in the Middle East. Troops can be withdrawn from Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, Kuwait, Turkey and god knows where else. Remove Saddam and there is suddenly no need for it. True, it will take some years to get Iraq Inc up and running the way we got Japan Inc going 50 years ago, but it will happen.

With Iran moving towards liberalization; with Iraq a capitalist democracy and with the Russians building a huge new oil terminal in Murmansk for sales to America, we not only get cheap oil… we undermine the very tool which allows Saudi’s to support billion dollar terrorist movements.

And then there are the Cold War leftovers in Europe… Another commentator I’ve read recently – where I unfortuneately do not recall – has suggested Rumsfeld wants to return the US to its classical military stance: a sea power. Maritime powers do not need large numbers of troops permanently based around the world. They only need ports for repair and refueling.

Where else are we pinned down? Korea… 37,000 Americans in harms way on that hellish armistice line. It is a no-man’s land of a half century old war that has never ended. Rumsfeld’s latest move in Korea is telling. US troops are to be pulled back. They will no longer be the Korean’s border canary.

SecDef Rumsfeld has stated in a number of recent public appearances South Korea has an economic capacity over thirty times that of North Korea and should be able to defend itself. He has suggestd it would be better for our soldiers and their families if they were based at home rather than in long overseas rotations.

In each area where there are large permanent American troop deployments, we see disengagement. It might take a war in at least one case to get us extricated. We are getting extricated nonetheless.

There is even a bonus prize. The UN is about to self-destruct. Put it all together and project ten years into the future. We see an America with a powerful naval and air force; with relatively few soldiers based outside the nation. An America looking out for its’ own interests and finally rid of most of the “entangling alliances” brought about by World War II and its’ aftermath.

We’re at the start not of Empire, but of the return to Fortress America… with a global reach via naval and air capacity to handle anyone who comes to our shores looking for trouble.

I think I could live with that.

The following stands out among the many comments to my previous post on Iraq.

How much is an Iraqi life worth? To me personally, about zero. Here’s why:

– I have no friends in Iraq (and doubt I ever will by the end of this post)

– No Iraqi signs my paycheck

– No Iraqi makes anything special that I can’t buy anywhere else (oil?)

– Iraq is on the other side of the globe

“But they’re being killed” you say. So are many other people. What about the North Koreans? What about the people who will effectively be killed because they cannot afford medical care due to this war? What about third world countries where parents have more children than they can afford to feed? Please make an objective, logical argument why the life of an Iraqi rates above (not just equal to) these others.

There are two issues in this comment. One is the old boring question “Why Iraqis and not North Koreans, or Chinese, or any other suffering people?” We have repeated countless times here on Samizdata.net that we do not consider lives of Iraqis above other individuals suffering elsewhere. Yes, I do want the world to be rid of North Korean, Chinese, Iranian and any other statist murderers. By yesterday, if you please. It’s long overdue and given that my taxes also pay for the army (or what’s left of it), I have no hesitation in supporting its use in cases when this becomes part of a government strategy.

The fact that the US and UK government policies are temporarily aligned with my view of the world does not redeem them in my eyes or make them somehow better entities. My objections to the state and my hatred of anything statist is not negated by my support of Bush and Blair in their determination to give Saddam his due. Samizdata’s eye will watch over the American attempts to establish democracy in Iraq with the same vigilance as ever and hurry to point out any misdemeanour by the inherently collectivist and kleptocratic state.

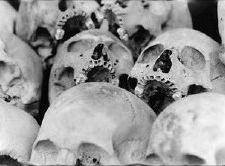

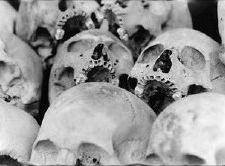

More importantly, the comment touches on an issue far greater than Iraq and the international pandemonium associated with it. Why do most of us hate to see people suffer? Why should we be moved by a sight of a child corpse, a woman tortured or a man shot? Why does the world remain shocked, moved and outraged by the suffering endured by those in Nazi concentration camps and Stalinist gulags (although unfortunately too few pictures serve to fuel the horror over those)?

I do not count myself among the emotionally incontinent (public expressions of grief) and the emotionally unsatiated (reality TV). My outrage comes from the belief that an individual is more important than a lofty idealistic concept, more so since every ‘utopia’ has built its edifice on a large pile of human bodies. The more idealistic and utopian the vision, the longer it takes to defeat it and the larger the ‘mountain of skulls’ left behind.

Savonarola’s Florence, Robespierre’s France, Stalin’s Russia, Hitler’s Germany, Mao’s China, Pol Pot’s Cambodia, Kim Jong-il’s North Korea, Saddam’s Iraq, note that there is an individual’s name attached to every totalitarian nightmare. We are forced to ‘care’ about them, whether we like it or not. If we are lucky, we have not been affected directly, but they certainly had an impact on the way we live today, simply as a result of the international politics shaped by their existence. → Continue reading: Old style morality…

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|