We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The other day I wrote a post about the plight of the Bushmen living in the Kalahari desert in Bostwana.

Jaded Voluntaryist commented,

Survival International are a bunch of arseholes who would see brown skinned human beings being prevented from rising out of the mud because it’s just so quaint. I wouldn’t take their word for it. Of course that may not be what’s happening here, but they don’t have a great track record.

They moaned for example when the Saint family (at the cost of several lives) brought Christianity to the Huorani tribe in Ecuador, which helped reduce their murder rate down from somewhere in the 70% region. Hardly anyone lived to old age. No one would deny that not everything the Huorani got from contact with the developed world was good, but only a sociopath would want them to keep living as they were.

I replied,

I take your point about the patronising attitude of groups like Survival International, although I have also heard that they sometimes do good work on the ground protecting tribal people from state and other violence. As I am sure you agree, if any particular Bushman wants to carry on as his or her ancestors did, good luck to them, and if he or she wants to head to the relatively bright lights of Gabarone and seek their future there, good luck again.

However it looks very strongly as if the Botswanan government has taken away the option for Bushmen to live in their traditional way by the use of a mixture of force (eviction from their ancestral hunting grounds and the hunting ban) and state “help” (the infantilising effects of welfare as pointed out by Mr Kakelebone).

I may write a post someday about the superiority of the attitude of Christian missionaries towards tribal people compared to the attitude of groups like Survival International towards tribal people. My argument would not be based on the fact that I am a Christian, nor on any general assessment of how much or little I admire the hunter-gatherer lifestyle (which might vary widely between different groups). My argument would be that the missionaries wish to persuade some other human beings to believe as they themselves believe, whereas the “protectors” wish to keep them as living museum exhibits. They always remind me of those science fiction stories in which Earth is kept ignorant / keeps other planets ignorant of faster than light travel and so on. My sympathies are nearly always with those who say, “Screw the Prime Directive”.

Then I said,

Come to think of it, screw the “I might write a post someday”. I will cut and paste the above comment as a post right this minute.

He also maintained homes in Colombia, Barcelona and Paris and continued to keep up his friendship with Fidel Castro, who gave him the use of a villa in Havana. During García Márquez’s frequent visits to Cuba, Castro would call on him as often as twice a day; the two men went fishing together, and talked about books and the nature of absolute power.

– from the Telegraph obituary of Gabriel García Márquez

This io9 piece reports that a musical based on Ayn Rand’s Anthem will open, in New York, on May 29th.

There is a website, where you can read this:

Anthem is told through the words of Equality 7-2521, in diary form. Equality 7-2521 is a young man who lives in the future after a time called the “Great Re-birth”. The city in which he lives is surrounded by an immense forest which is thought to be impassable due to the fact it is filled with wild animals. This is a simple and isolated society in which all technology is carefully controlled and in its most primitive state. All awareness and understanding of individualism has been lost and words such as ‘I’, ‘me’, or ‘mine’, do not exist in spoken or written language, therefore, nearly the entire story is told in the ‘first person plural’. Independent thoughts and/or actions are strictly prohibited by law and therefore, everyone lives and works in groups as a collective body also known as the “Great We”. …

It will be interesting to see how well it does.

Today’s big political story in the UK is the resignation, due to expenses she had claimed, of Maria Miller. Her ministerial post had been that of “Culture Secretary”; her brief had included the role of regulation of the media, and the whole wretched power-grab known as the Leveson Report.

It won’t have occurred to most of those in the Westminster Village who write and chat about such things, but for me, as a slash-and-burn small-government type, what I’d like to think of is that we get rid of such an Orwellian-sounding post as “Culture Secretary”.

The business of sport, media and the arts should not be under the control, or even vague oversight, of the State, in my view. Since when, for example, have the doings of Premiership footballers been the proper concern of politicians? In an age of crowdfunding platforms, and due to the continued philanthropic involvement in such matters, as well as plain good entrepreneurship, why should money be forcibly taken from people in tax to spend on art galleries or whatever? Why should a state interest itself in how the television industry is run (abolish the BBC licence fee, etc)? Getting rid of this ministry would be a part of a wider retrenchment of the State to what arguably are its core functions. At the very least, the scrapping of this post, and the associated quangos it deals with, would signal that we haven’t given up on the noble idea of rolling back the State.

Needless to say, I am dreaming impossible dreams. It may have something to do with it being such a gloriously sun-kissed April morning here in London.

Have you ever heard or read a speech in real life or fiction that left you inspired, moved, exalted, perhaps even blinking back tears… only to remember a minute later that you fundamentally disagreed with every word?

One of the saddest recent facts about the world, and especially the twentieth century world is that the Devil has tended to have the best tunes, the best pictures and the best public sculpture.

By the middle of the twentieth century, World War 2 having been at least partly won by some of the Good Guys, many officially encouraged Artists in the rich West had come to associate all tunefulness and all pictorial or sculptural communicativeness with evil, and to shun artistic communicativeness on purpose. Is this picture telling a story? Does that symphony have lots of tunes? Is this sculpture of something or of someone, and does it speak to the best in us? To hell with that, said many of the more serious and educated sorts of Artists, because such glories reminded them that Artistic glory had just been and was typically then still being used, by Hitler and by Stalin and by their numerous imitators around the globe, to glorify wickedness.

Meanwhile, the horribly numerous and influential supporters within the better bits of the world of the still persisting and Communistic sort of evil went out of their way to encourage these mostly dismal and arid Artistic tendencies, in order to make the best bits of the world seem far more uninspiring than they really were, and hence ripe for conquest by the Communistically evil bits. Artistic glory continued, well into the late twentieth century, when the very worst of the twentieth century’s greatest horrors were politically and economically in retreat, to glorify the dreary and still decidedly evil aftermath of the horrors, in the USSR and in all the places it continued to subjugate or influence, such as in China and nearby despotisms. The rule was, still, that the better the mid-to-late twentieth century place was and the more it was contributing, despite all its corruptions and blunders and disappointments, to the ongoing advance of humanity out of mass poverty and into mass comfort and even mass affluence, the duller and more uninspiring its officially sponsored Art was.

Thank heavens for the less official, small-a art, like advertising and the more commercialised parts of cinema and television, and like pop music. Above all, thank heavens for rock and roll. If Official Art refused to celebrate the escape, in the rich countries, of the poor masses from their poverty, then the enriched paupers would buy electric guitars, form ten million pop groups and celebrate their newly emancipated lives for themselves. The rock-and-rollers didn’t “build this city on rock and roll”. The city was already built. But by God they cheered it up. And this despite all the efforts of Official Art people to make rock and roll dismal too.

These thoughts were provoked by me recently having been steered towards pictures of this, I think, rather splendid piece of public sculpture on a hill in Africa, just outside Dakar, Senegal:

This gigantic and inspiring celebration of human progress and traditional family values was erected by the sculptural propaganda arm of the abominable state of North Korea, that classic after-echo-of-horror relic that still now staggers on into the twenty first century.

To the exact degree that Africa is now starting seriously to shun the follies of North Korean style murder-suicide-statist political-economic policies, Africa is indeed now starting to make some serious economic progress, thanks to things like free trade, mass literacy and mobile phones. Well fed African go-getters with adoring wives and happily well fed babies are now multiplying across the continent, busily exploiting the potential of such things as mobile phones to stir up affluence, for others as well as for themselves, perhaps some of them even inspired in their capitalistic endeavours by sculptures like the one above.

I personally believe that the famously colourful and inspiring Chinese posters that were among the very few pleasing things created during the otherwise wholly dreadful and destructive Mao-Tse-Tung era in China may have had a similarly inspiring impact upon China’s subsequent generation of capitalistic go-getters. Communists had a minus quantity of knowledge about how to create the good life, but they at least had a clue about what the good life looked like and felt like, and got other and less crazed persons thinking about how actually to contrive it.

Meanwhile, public sculpture in the old rich parts of the world has, for some time now, been on the up and up, or so I think. It may not be gloriously inspiring, but at least it has started to be – has for some time actually been, I think, some of it – fun, at least quite often. Official Art still can’t quite bring itself to be as brashly optimistic about humanity and its future as those North Koreans, but at least the baleful representation-equals-Hitler-and-Stalin equation is sinking into the cultural history books. Good riddance.

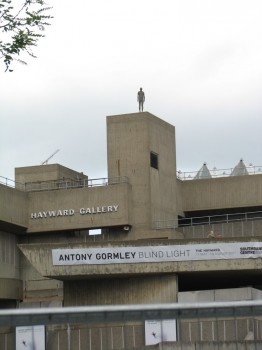

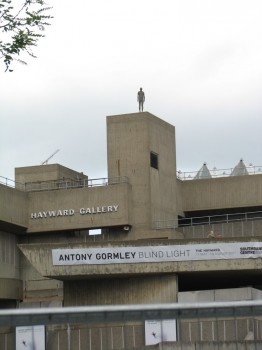

Personally, and in company with many other people who are not usually very attracted by or admiring of contemporary Art, I particularly like the works of Antony Gormley. There was recently a show about Gormley on BBC4 TV, which illustrated only too vividly that Gormley emits the same drone of vacuous and pretentious Art-Speak nonsense that most other Artists seem to. The contrast between the educated verbal gropings that Gormley talked on TV last night with the down-to-earth clarity achieved by the comic book artist Frank Quitely, who starred in an earlier BBC4 show in the same series, was extreme (see my remarks above about the redemptively inspirational contribution of popular art to Art). But ever since Gormley stumbled into popular acclaim with his Angel of the North, which proved a whole lot more inspiring to the wider public than he probably thought it would, he has specialised in doing public sculpture that is of something (typically his own very average naked body but never mind), and which many people, me included, often enjoy looking at. His actual work is, I think, as often as not, brilliantly eloquent, and he is now finding it easier to do it, what with the new technology of 3D computer scanning and visualisation and 3D printing. Gormley’s actual Art makes me want to say, not so much that his spoken words are silly (even his sculpture titles tend to be Art-Speak meaninglessness), but that words are just not Gormley’s thing.

I still remember fondly the time in London, in the summer of 2007, when the dreary concrete of London’s South Bank Arts district and nearby parts was invaded by a small army of naked metallic Gormleys. The many identical Gormleys were not, in themselves, especially inspiring. But look on the bright side. Nor were these Gormleys bent-out-of-shape semi-abstract grotesques, mid-twentieth-century style. And although in themselves ordinary, the Gormleys were often standing in very interesting and inspirational places, high above the streets, up on the roofs of tall buildings:

Stick anyone on a pedestal – in general, look up at them – and they look more impressive. They look like they deserve to be looked up to. This positioning of all those South Bank Gormleys suggested (yes yes, to me – I admit that all this is very personal) ordinary men at least looking, very admirably, towards less ordinary and more inspiring far horizons. Some of the Gormleys were looking downwards, but most were looking out ahead. What all these Gormleys were not doing was just standing in Art galleries, staring miserably at their own feet, with signs next to them full of demoralising Art-Speak drivel. They raised the spirits of almost all of those who gazed up at them. Only those Art People who hated what a popular hit the Gormleys were and who still want Art to just moan about the horrors of capitalist consumerism, instead of actually making a positive contribution to this excellent trend in human affairs, were seriously offended by all these Gormleys, which for me is of course just another reason to love them and to treasure the memory of them. I and most other Londoners and visitors to London who saw them regretted only the moment when they migrated elsewhere.

If and when the ghastly government of North Korea is overtaken by the collapse that in a wholly just world would immediately engulf it, I wonder what will happen to these North Korean sculptors. I now like to conjecture that, despite all the barbarism that they now go through the motions of glorifying, they might yet have some kind of civilised future, glorifying people and things that truly deserve to be glorified.

Why I wuvs capitalism, part Umpteen Hundred and Two.

No. 6: Bach on a Japanese forest xylophone. It’s actually a mobile phone advert.

Many of us libertarians complain about how our anti-libertarian adversaries seem to do so appallingly well in attracting support from celebrities, and most particularly from showbiz performers. I agree with what Johnathan Pearce said here about this yesterday. Showbiz people are and should most definitely remain entirely entitled to express their opinions about politics or about anything else. But, they must then be willing then to be criticised by those who don’t agree with what they say, just like any other opinion-monger. JP makes a point of mentioning by name some showbiz people whose thinking he admires, which is also good. But I often hear other libertarians indulging in blanket condemnations of the thought processes of all showbiz people, declaring them to be inherently less capable than others of thinking clearly and arriving at wise political ideas. They then go on to curse the world for paying so much attention to these terrible people.

Quite aside from the obvious fact that many showbiz people are very smart, this is a tactically very silly way to think and talk. Showbiz people have at the very least demonstrated their expertise in communicating, in engaging with audiences. Many of the curses aimed by libertarians at showbiz people whose political views they do not agree with sound to me more like sour grapes than serious argument. Most such complaints would surely cease if we libertarians were to start attracting showbiz people to our cause in serious numbers. Meanwhile, if we think that showbiz people typically proclaim bad political ideas, then our task is to persuade such people to think better and to proclaim better ideas, rather than us merely moaning that such people somehow have no right to be heard opining at all, about anything except showbiz. Maybe it is in some ways true that celebrity opinion-mongers shouldn’t be paid attention to, as much as they are. But they are, if only because being paid attention to by lots of people is the exact thing that these people specialise in being very good at. Maybe people are foolish to get their foolish political ideas from politically foolish showbiz people. But many do. Whether we like it or hate it, recruiting at least a decent trickle of showbiz people is a precondition for us achieving any widespread public acceptance of our ideas.

I also believe that showbiz people may have quite a lot to teach us about how to present our ideas persuasively.

The above ruminations being all part of why I find Dominic Frisby such an interesting and appealing individual. He is an all round actor and entertainer and voice-over guy, and he is in particular an experienced and successful stand-up comedian. He is also a libertarian, and he has recently written a book called Life After The State, which I have recently been reading. I think it is very good, and I have already given it and its author a couple of admiring mentions here.

On the back cover of Life After The State, Guido Fawkes says:

Things are so bad that in our time only a comedian can make sense of an economy based on printing money.

This makes Frisby sound like a British P. J. O’Rourke, which is to say a writer who uses politics to get laughs, and laughter as a way to think about politics. But although it is true to say that Frisby is a comedian who writes about politics, he does not write about politics to get laughs, or even make much use of laughter to get attention for what he writes. The comedy experience that Frisby has brought with him to this new and distinct task is the experience of having to make himself clear and to hold the attention of an audience. If a comedian’s audience loses track of or interest in what a comedian is saying, it won’t get his jokes and it won’t laugh. But what Frisby wants with this book is not laughter, but to be understood. There is plenty of wit. There are plenty of felicitous phrases and nail-on-the-head, SQotD-worthy sentences. But a laugh a minute this book is not.

So, if Frisby is no longer playing the comedian when writing his book about the state of the world and about why the state of the world would be better if there was less statism in the world, what kind of arguments does he present, and how does he present them?

There was a big clue in the talk I recently heard Frisby give at the Institute of Economic Affairs, the one I mentioned here in this earlier posting. In the course of this talk, Frisby described himself as a “bleeding heart libertarian”.

Now there’s a phrase to raise Samizdatista hackles, to cause rats to be detected, red rags to be charged at. The suspicion here will be that anyone who self-identifies as a bleeding heart libertarian is not really any sort of libertarian at all, and probably more like a traitor in our midst. I have not read enough from other self-identified bleeding heart libertarians to know how true or fair such accusations are. (That link is to a piece at Counting Cats, but it is by a regular commenter here, “Julie near Chicago”.) What I definitely can report is that the particular bleeding heart libertarian who is Dominic Frisby is definitely not guilty in the way that this label might here cause him to be charged.

Frisby starts out, in Life After The State, by describing what is wrong with the world, the kind of sufferings it contains, the kind of wrongs in it that ought to be righted. There is huge inequality, not just in matters of what people get paid for the work they do, but in things like healthcare and education. What the wrong kind of bleeding heart libertarian presumably argues, or is accused of arguing, is that because poverty is terrible and because poor people ought to get better healthcare and education than they do now, and because all decent people want the best not just for themselves but for people generally, and especially for the poor and the unlucky, well, that means that we need to soften our line on such things as state welfare, state education, the national health service, and the like. But what Frisby says is that because people at the bottom of the heap ought to get better chances in life than they now get, that is why unswerving and principled libertarianism is the absolute right thing, no ifs no buts. He doesn’t word it quite as belligerently as that. He does not constantly italicise, the written equivalent of banging the table. He is Dominic Frisby. I am merely me. But I trust I am clarifying the distinction that I am trying to clarify.

All of which is central to the project of persuading people generally, and showbiz people in particular, to become libertarians. Showbiz is full of people who want all that is best for everyone, but who are, as part of all that, very wary of aggressively eloquent rationality. (Typically, this is how their villains talk.) What they want to know is whether your heart is in the right place. Do you even have a heart? If you do, does it ever bleed? Yes, yes, we hear what you think. But what do you feel, and what do you feel about what others feel? Do you want the best for everybody, or do you merely want the best for your nasty, boring little self and your nasty, boring friends?

For well over a century now, that particular brand of collectivists called socialists has done a brilliantly successful job of convincing people generally and showbiz people in particular of socialism’s niceness. Socialism, say the socialists, is about wanting what is best for everyone. Socialism’s opponents may be all very clever and rationalistic and skilful at advancing their own arguments and interests, but they are all of them heartless, uncaring bastards, at best deluded. As a result of this relentlessly successful line of argument, millions of people who really do want the best for everyone have flocked towards socialist banners. Yes, many socialists have been cynical and manipulative, and more like the kind of people that most socialists complain about. But, say the other socialists, bad socialists like that are bad because they betray socialism, they fail to do socialism. They are traitors to the cause. Socialism could never have had the colossal and colossally damaging impact that it actually has had, if the leading socialists had all come across as mere schemers and contrivers and arrangers with no hearts, and still less if all the other socialists attracted to the cause were like that also.

Dominic Frisby’s father was the noted playwright Terence Frisby, and Terence Frisby was himself a socialist. But the thing that is wrong with socialists like Terence Frisby is absolutely not that their hearts bleed. They want a kinder, more generous, more fair, more comfortable and more entertaining world, especially for those who are now very poor and very unlucky, and good for them. Their folly is in supposing that the way to contrive these outcomes is for socialism to be inflicted upon the world, and for freedom to be done away with.

In short, Dominic Frisby is both a nice guy and a clever guy, and a notably effective and significant contributor to the libertarian cause. When some of his many showbiz friends take a look at his book, as some of them surely will, they may find themselves surprised at how much they agree with what it says.

Learn more about Frisby and his ideas by exploring his website, by reading his stuff, and watching some of his video performances and creations.

Or, be at my home in a week’s time, on the 28th of this month, when Dominic Frisby will be giving a talk on the subject to which his second book will be devoted, namely Bitcoin, crypto-currencies, etc. Confusingly, a lady called Dominique was to have been my speaker that evening, but she had to postpone and will now be speaking at my last Friday gathering on May 30th. Meanwhile, February 28th turned out to be a date that was just right for Dominic, because he is now eager both to find further readers for his first book and to sign up members of the crowd which will be crowd-funding the publication of his second book.

The crowd-funding of books, especially of books intended to persuade rather than just to entertain, being a subject that deserves an entire posting to itself.

“I’m thinking of making T-Shirts for Guardian readers and Progressives. The first one would say: I GET MY OPINIONS FROM MILLIONAIRE ROCK STARS AND ACTORS.”

Taken from a comment by someone called Stuck-Record at Tim Worstall’s blog. Tim was describing how he left a comment on an article by the actor, Bill Nighy, in defence of a “Robin Hood Tax”; Tim’s comment – which he said was entirely civil – was deleted. The Comment is Free site of the Guardian clearly cannot take dissent from some pro-marketeers. (I expect Tim drives them mad with his dissection of their views on a daily basis.)

The red lights on the mental dashboard go on in my head when the words Robin Hood come out. The false assumption of the tax proponents is that you can tax an activity – such as bank trading – without the impact in any way being felt by us ordinary folk. More cynically, politicians might like the idea because the actual cost impact will not be easy to see (wider bid/offer spreads for exchanging money, lower returns to investors, cuts to service and jobs in banks, etc.)

Of course, not all actors and music folk have collectivist, interventionist views on things like economics, or other things. The US actor Rob Lowe seems pretty intelligent, ditto Clint Eastwood, Michael Caine, etc. I don’t have a problem as such with actors/others talking about such things – we should not fall into the ad hominem fallacy of saying that non-specialists on subject A cannot talk about it (democracy is based on such a position, is it not?). However, actors, singers or whatever who want to get into the arena cannot expect to be treated any more gently than an economist or other specialist in an area of controversy. Being a luvvie doesn’t get you special favours.

One commenter managed to get past the CiF “checkpoint Charlie” to leave what I thought was a pretty good point:

The whole flaw is laid bare in this one sentence – a tax can be tiny or it can raise billions, it is unlikely to do both. Those billions you claim can be raised are a powerful incentive for organisations to circumvent the tax; on something as ephemeral as financial transactions that’s quite easy to do. It would merely hand volume to New York, Hong Kong or Singapore.

Of course France, Germany et al are in favour of it. It would be a EU wide tax that would fall most heavily on the UK and you even point out that a whopping 50% of the money raised could be spent on domestic causes – oh fantastic, we adopt a tax that could be damaging to one of our major industries and get to spend half of the proceeds on our own country. Do you honestly believe that Germany would accept a similar deal in relation to a green tax on luxury motorcars or France on farming?

As I often like to say and to write, if I don’t regularly quote me, who else will? And once upon a time, I wrote (on page 4, left hand column, of this), in a paragraph about the many different ways there are to be an effective libertarian, this:

Or perhaps you contribute crucially to the cause simply by (a) calling yourself a libertarian when asked what you are but not otherwise, and (b) being a nice person in all other respects. By merely proving that libertarianism and decency can cohere in the same personality, you will be a walking advertisement for the cause, as I might not be.

Now I don’t want to accuse Frank Turner of regarding himself as a member of any sort of political team, any sort of promoter of a “cause”. He is first and last a musician and an artist, not “a libertarian”. But the more I learn about this man (and thanks to Google sending me emails whenever anyone mentions him I have been learning quite a lot about him lately), the more he strikes me as the living embodiment of the above notions. It’s not that he is incapable of arguing his political corner. Merely that, on the whole, he prefers not to, and just to get on with his work and his life.

Consider this Frank Turner interview piece by Anna Burn, published today by Cherwell.

Near the beginning, Burn writes of the “clear tension” between Turner’s “old, anarchist politics and his new libertarianism”. And at the end of her piece, she writes this:

“People have historically been quite rude about rock and roll as serious art,” he says. “To me rock and roll is proper art, but it’s also disposable art, it’s adolescent art. What’s great about rock and roll is that it’s music about being young and pissed on a beach and getting your first kiss and then dancing until dawn. Sometimes people want to make rock and roll into this high art and I love it because it’s low art. It’s almost a sort of Liechtenstien thing. It’s pop art.” He grins wryly, seeming pleased with the pun. “All my influences are rock and roll.”

And with that last declaration, we’re done. As we’ve been talking he’s been putting his coat back on so that he can dash down to catch a train to London and film his tribute to Pete Seeger for Newsnight. For a man who’s on his longest break from touring in seven years, he’s still remarkably busy, and yet he can still spare a few minutes to chat to a student newspaper.

As he runs down the stairs, I realise that this is why he is a true folk singer – he’s open to everyone prepared to engage with his work, and he makes it worth their effort.

Note the Pete Seeger reference. This is not a man who allows a thing like politics to get between him and an admired fellow musician. See also Billy Bragg.

A few weeks ago, when the weather was crap – as it still is – and I knew I’d be spending some evenings at home, I opened a box-set of DVDs to watch that classic Sixties TV series, The Prisoner, starring Patrick McGoohan. Many things have been written about this series, which in my view represents one of the best such shows ever made. Chris R Tame , the late UK libertarian activist, mentor and friend of mine, wrote a fine essay about this show in the early 1970s and I agree with every word of it. The show is intelligent, profound, thought-provoking, and now thanks to the wonders of digital remastering, looks as fresh today as when it was first produced. (So much so that it seems almost better than if it were made now.) I was born in 1966, roughly time the show was conceived, written and shot. Some Sixties series can look very dated today, however much fun they are (like the old Avengers with Diana Rigg, etc) but The Prisoner doesn’t. And boy, is it on-target now. In the age of surveillance cameras, nanny statist health campaigns, the Leveson recommendations on state regulation of the UK press, unaccountable quangos, the NSA, and the like, much of what is lampooned in The Prisoner is all too believable.

Some time after he made The Prisoner, and had gone back to live in the US, the country of his birth (he spent a large amount of his adult life in the UK), McGoohan had these thoughts about the show and why he made it. I wonder what actors are as emphatic in stating such a viewpoint today:

“I tried first of all to create a first-class piece of entertainment. I hope it rings true because here, too, I was concerned with the preservation of individual history….If I have any kind of drum to beat in my life it is the drum of the individual. I believe that to be truly an individual, mentally clear and free, requires the greatest possible effort. And I seek this individuality in everything I do – in my work and in my private life. It is not easy.”

It isn’t. The other day, I had a bash at UK journalist and controvertialist Peter Oborne for his claim that a game such as cricket should not be primarily about people having a fun time, of doing something that makes them happy as individuals, but because it helps obliterate the self, that is about a “duty” to a nation, or some Other. I don’t know much about McGoohan’s explicit political views, but something tells me he would have regarded Oborne’s bullying anti-individualism about something like a ball game with bemusement, if not contempt.

For every type of crime there are false victims as well true ones, suggestible and forgetful witnesses as well as witnesses whose recall is accurate, scam artists digging for gold as well as honest people bravely speaking out to bring monsters to justice. The existence of cynical liars, fantasists, and well-meaning but tragically mistaken people is part of the human condition and always will be. That is why any half-way civilised society has trials and rules of evidence instead of just declaring people guilty or innocent by category.

Coronation Street star Bill Roache found not guilty of rape and assault, reports the Telegraph.

and in a separate article,

Bill Roache not guilty: high-stakes gamble backfires for CPS

Accusations that the Crown Prosecution Service has indulged in a “celebrity witch-hunt” gather strength as Coronation Street actor found not guilty of all charges

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|