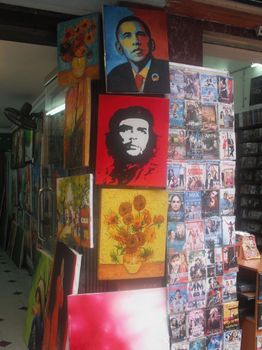

My apologies about the blurry photo. I was a little preoccupied with other things at the time. Not that I would do anything to encourage speculation.

|

|||||

|

People sometimes ask me why I travel, and how I choose where I travel to. Let me give a recent example. I have recently been making an effort to fill in gaps in my knowledge of modern European history. In particular, I have been attempting to learn about the Napoleonic Wars, and the subsequent growth of Prussia and its evolution into the German empire. The remnants of Europe’s 20th century history are obvious and everywhere, but the remnants of earlier upheavals are equally there if you look for them. I have a certain penchant for looking at odd and peculiar remnants of the past, sometimes big, sometimes small. When in Poland late last year, for instance, I found myself visiting the remains of the mausoleum of Prussian General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, victor alongside the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. This was desecrated by the Red Army in the closing days of the Second World War – Russian soldiers used the general’s skull for a game of football when doing so – and is not particularly easy to find these days, as Poland does not exactly advertise its presence, but it is there if you look for it. And when reading about those same wars, I discovered an interesting fact: that there is an outstanding territorial dispute between Spain and Portugal from the same era. The river Guadiana forms the approximate border between Spain and Southern Portugal, although there are significant pieces of land that are east of the river and nonetheless part of Portugal. There used to be more. The town of Olivenza (in Spanish) / Olivença (in Portuguese) was Portuguese from the thirteenth century until the nineteenth (full details here). However, as Portugal allied itself with England in 1373 and the Spanish kingdoms were more often allied with France or other continental European powers, European wars along with local rivalries meant that the border was often fortified and there were various military skirmishes in the area over the centuries. For instance, the Ajuda Bridge across the Guadiana (which like many bridges in rural Portugal is often claimed to be Roman but which was actually built in the 16th century) connecting Olivença to the nearby Portuguese town of Elvas, was destroyed in 1709 during the War of Spanish Succession. Lack of resources, continuing instability, and the devastating earthquake of 1755 prevented it from being rebuilt before Olivença fell to the Spanish in the War of the Oranges in 1801, and was ceded to Spain in the Treaty of Badajoz that same year. One article of that treaty stated that if either side breached any article of the treaty, the whole treaty was void. Spain and Portugal went to war again in the Peninsular War of 1807, at which point Portugal claimed that the Treaty of Badajoz had been abrogated as a consequence. Upon the final defeat of Napoleon, Britain promised to aid Portugal in achieving the return of Olivença, and a clause was inserted in the Treaty of Vienna in which it was agreed that the powers would “endeavour with the mightiest conciliatory effort to return Olivenza to Portuguese authority”. After a bit of foot dragging, Spain signed the treaty. And that is where we are today. Spain occupies Olivenza to this day, stating that agreeing to “endeavour with the mightiest conciliatory effort” is not the same as agreeing to do something, and claiming that the Treaty of Badajoz is still valid. Portugal rolls its eyes at this, and states that the Peninsular War makes the Treaty of Badajoz null and void anyway, plus Spain agreed to give Olivença back under the treaty of Vienna. The Napoleonic wars apparently continue on this small corner of the Iberian Peninsula, just as the Franco-Prussian War apparently still goes on in Liechtenstein. In practice, nobody gets too worked up about this, as modern relations between the two countries are good. Before Christmas, I learned all this and I thought it was kind of interesting. In addition I was able to get a very cheap airfare to Faro on the Algarve and a cheap car rental when I arrived there. Plus the forecast in London was for heavy snow, and I wanted to get out of the cold for a few days. Plus I always have a lovely time when I go to Portugal – especially when I drive into the interior. There is a certain cliche of rural France (much represented in French cinema and much parodied in Stella Artois commercials) that seems largely gone when one visits rural France. One still finds it rather more in rural Portugal, and I find this rather charming. So, the plan was set. I would fly in, have a look at the coast, and drive up the Portuguese side of the border, roughly following the Guadiana river, ultimately ending up at Olivenza. I would look for lingering signs of Portugueseness and resentment from the Napoleonic wars. If I had time, I might then head for the coast near Lisbon, look for the location used in a music video of a song by a Romanian pop princess that I had viewed in a bar in Transylvania a couple of weeks earlier, for no particular reason other than it reminded me a little of home. → Continue reading: Do or not do. There is no endeavour with the mightiest conciliatory effort When I was in Vietnam last week, I caught up with fellow Australian expatriate Samizdatista James Waterton. James presently works teaching English in Vietnam to people preparing to attend Australian universities, and prior to moving to Hanoi lived in Beijing for several years. During this time he wrote for us about both Chinese, other Asian, and Australian affairs. Really good anonymous stuff on China was occasionally known to appear on this blog during this period, also. After James guided me to a number of fine culinary establishments (as one would expect from one of the world’s great authorities on soy sauce) and gave me a tour of the main sights of Hanoi from the back of his motorbike, the two of us sat down in a cafe on the second floor of a building mysteriously shaped like a ship in central Hanoi, where we recorded a conversation about what was on our minds. This included our experiences as expatriates and our opinions on economic growth in Asia in general and China and Vietnam in particular, the outlook for the Chinese nation and economy, the differences between the the authoritarian habits of the Chinese and Vietnamese governments, ways in which people in poor countries now in some ways have greater and easier access to modern technology than do people in rich countries, and (surprisingly related to this) the correct etiquette for visiting the embalmed body of Ho Chi Minh. There is a little bit of background noise in this recording, much of which is the honking of motorcycle horns and other street noise coming from outside the cafe. I think the conversation is quite easy to follow despite this, so I shall just refer to this as “ambience that adds to the listening experience”. Enjoy. Update: The link pointing to the post on soy sauce was incorrect. This is now fixed. Just out of interest, although this couple were watching a movie together on an iPhone screen in an impressive display of marital harmony, they did have his and hers iPhones regardless. Perhaps even more impressively (if you are Steve Jobs, anyway) all five people in my row on the plane were at one point using iPhones or iPod touches simultaneously. I think all of us would have our experiences enhanced using the larger tablet. On the other hand, Apple victim as I am, I don’t think I will be getting one myself. For me, the killer issue is the lack of an SD card slot. Normally, I travel with a netbook, and I am constantly taking photographs and backing them up. I do not want additional accessories that I have to remember to bring with me and can lose along the way. I certainly do not want additional accessories that have proprietary Apple connectors and that I cannot replace in obscure shops in strange parts of the world. No SD slot but works with USB card reader = annoyance. No SD slot and card reader with proprietary connector = deal breaker. This is a shame, because iPad as media player, web browser, and photo management tool that would import my photos to iPhoto and then sync with my Mac when I got home would be great. Plus there is the small matter of VLC and a bit-torrent client, which for unstated reasons that are fairly obvious, are much more useful to me when on the road than when at home, but let’s not mention that. This may be less of a deal breaker, as I suspect there are teams of jailbreakers and hackers on the job already. This development may horrify the old guard, but peer-to-peer review was just what forced the release of the Climategate files – and as a consequence revealed the uncertainty of the science and the co-opting of the process that legitimizes global warming research. It was a collective of climate blogs, centered on the work of Stephen McIntyre and Ross McKitrick, which applied the pressure. With moderators and blog commenters that include engineers, PhDs, statistics whizzes, mathematics experts, software developers, and weather specialists – the label flat-earthers, as many of their opponents have attempted to brand them, seems as fitting as tagging Lady Gaga with the label demure. – Patrick Courrielche, discussing the circumstances by which the Climategate e-mails came to light and were analysed by independent parties. Parts two and three of his article are unnecessarily on separate pages. I confess that I do like the phrase “Peer to peer review”. I am struck by how much of the progress here has been made by the so called “lukewarmers” – people who are (or at least were) open to the idea that global warming was real and human caused, who often had relevant expertise, and wanted to look at the data for themselves. After all, many interpretations are always possible. (First link via Bishop Hill). This is not a joke. Well, it is a joke. However, the Home Office does not seem to realise this. Reading the comments at The Register is always good value in times like this, too. Somebody please tell me that this is really a withering piece of satire dreamed up by Guy Herbert. Please. I will be in Dubai on January 16 and again on February 7-9, Singapore January 17-18 and again on January 29-31, the Gold Coast and Brisbane from January 19 to 28 (except January 25-26, when I will be in Sydney), Hanoi from January 31 to February 4 and Melaka from February 5-6. If anyone feels like buying me a drink in any of those locations, please let me know and I will see what I can do. People (like Anatole Kaletsky) who have the view that large quantities of government debt somehow don’t matter and are are not potentially damaging would do well to listen to this talk given by Professor Kevin Dowd, that I was fortunate enough to attend at the Libertarian International conference in Paris last September. An audio only version is here. The whole talk is good, but the first half (mainly about sound ways of recapitalising banks) is drier than the second. The really good stuff gets going at about the 20 minute mark. Update: For the first few minutes of this lecture, it seems that Professor Dowd is giving the same talk he gave at the Chris Tame lecture earlier in the year. However, this is not the case. He gets through that in the first half of the talk. It is in the second half of this that he really says exactly what he thinks, and it is refreshing to hear someone just come out and say these things. If you heard the earlier lecture, it is still worth listening to at least the second half of this one.  Alicante, Spain. January 2009.

I yesterday went shopping for an LCD television for a friend of mine. I went to Richer sounds (a splendid and rather uncharacteristic British retailer known for selling high quality electronic merchandise at low prices from relatively unfashionable locations where the rent is low, providing fine customer service and treating employees well), and I ended up buying a Sharp TV. Interesting company, Sharp. People sometimes think the name is a little odd. For what it is worth, the company originally made mechanical pencils for engineering purposes, and they wanted to make it clear that they were very sharp (true story). Japanese companies seem to divide into two kinds. There were pre-WWII monoliths – the so called zaibatsus. American policy after the war was that these were far too powerful and that they were to be broken up into smaller companies. This American policy failed. They zaibatsus were theoretically broken up into smaller units, but they retained a complex arrangement of holding companies and cross shareholdings in which management control largely remained in place even though the companies had theoretically been split up. They evolved into post war industrial groupings known as keiretsus. These companies remained politically well connected, and when Japan attempted to grow its exports through government directed industrial policy, these were the beneficiaries of it. These keiretsus included Mitsui/Toshiba, Mitsubishi, Hitachi, Matsushita (Panasonic), and others. As I said, these well connected companies were recipients of government largesse, and those who would wish to praise government industrial policy would tend to construct a story that this led to Japan’s industrial success in the 1970s and the 1980s. But of course, the story is more complex than this, There is a really good book about this, We Were Burning: Japanese Entrepreneurs and the Forging of the Electronic Age by Bob Johnstone. The interesting part of the story is that although the keiretsus did benefit from the growth of the Japanese electronic industry, they were not where its innovation came from. The companies that were the heroes in this regard were small, non-existent or unfashionable in 1945, or were discarded or disdained pieces of broken zaibatsus, In particular, we are talking companies like Seiko-Epson, Canon, Yamaha, or even Sanyo or Honda or Suzuki (the Japanese government tried to micromanage the car industry, but the motorcycle industry was seen as less interesting, and so that is where the interesting companies ended up coming from). In electronics, in the 1970s, Sharp’s research was led by Sasaki Tadashi, whose enthusiasm earned him the truly glorious nickname of “Dr Rocket” – personally I would almost kill for such. In that era Sharp pretty much invented the electronic calculator and the LCD display. Sharp remains a leader in LCD display technology to this day. To the extent, that in this day of LCD television, Sharp is the only Japanese company worth mentioning in this market. Sony – a company that rode a totally unique route between the keiretsu and the post war upstart, but which in the end did a better job of selling itself as a brand than an innovator – was the undoubted leader in the era of CRT televisions, but (perhaps as a consequence) totally missed the transition to flat screens. A lot of fancy televisions are sold today under the Sony brandname, but these were generally actually made by Samsung, or (in certain high end cases) by Sharp. The only Japanese company that actually makes televisions today is Sharp. The company that always was the great innovator: the company that Sony pretended to be. Which is why I was happy to buy such a set for my friend. My good friend Rob Fisher recently wrote the following on his own blog.

Yes, but Bob Geldof and Midge Ure wrote those lyrics, and they had this British preconception already. Another factor might be that the places in Africa that British people are most likely to visit are Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and South Africa: the Sahara, and the arid south. There is plenty of fertile land in the middle. A tragedy is that some of the most fertile parts of Africa tend to be some of the most troubled: the vast Congo basin is prime land, essentially, and yet its history has been unspeakable, at least since the arrival of King Leopold’s privateers in 1877. As Chris Moyles discovered, Uganda is green and fertile, but its history is not the happiest either. People who attempt to raise awareness of malaria in Africa and elsewhere, and to raise money for its prevention deserve praise, of course, but what I am struck by is that the story about mobile phones becoming ubiquitous in poor countries has only just reached these people. This story is at least five years old now in the sense that most people have access to one and probably closer to ten in the sense that mobile phones existed in these countries and networks have been quite comprehensive, in many cases as comprehensive or more so than in rich countries. A related story: about three years ago I was walking along the Thames path on a Sunday afternoon. and I passed City Hall. Outside the building was some kind of “Here is how bad things are in the third world and why we should fell guilty” kind of exhibition provided for us by Ken Livingstone’s lackeys using our money. Amongst the factoids of information in this display was the statement that “90% of the world’s population have never made a phone call”. The “x% of the world’s population have never made a phone call” meme has been around for a while. 90% is obviously ridiculous and shows intense innumeracy from whoever made it up. (About 15% of the world’s population lives in rich countries, and if you add “rich parts of middle income countries, you can increase this number to 20 or 25%). The meme seems to usually be stated as “50% of the world’s population have never made a phone call”. Clay Shirky attempted to investigate where the meme came from, and the first recorded statement of it appears to be from engineer Greg LeVert of telephone company MCI in 1994. However, he said it in the context of “.. but oh boy is this going to change with all the great new technology that’s in the pipeline”. Nobody knows where he got the factoid from though: he may have just made it up. However, the Al Gores and Michael Moores and Kofi Annans and the like (and even people like Melinda Gates and Carly Fiorina who should know better) have repeated it endlessly since – or at least were doing so until only a few years ago. It is, of course, just not true. It is extraordinary that people should repeat out of context a ten year old view of what the poor world is like, as if the ten years between 1995 and 2005 were static in the development of telecommunications. At the time I encountered that exhibition outside City Hall, there were around 3 billion active mobile phones in the world: so therefore, although 90% of the world’s population had never made a phone call, about 50% of the world’s population owned a mobile phone. (They were all big texters, apparently). Since then, the number of mobiles in the world has increased by a further 50% to around 4.5 billion. The number of people with multiple phones per person or separate voice and data accounts and such has now reached the point where you cannot go directly from this to “4.5 billion people have mobile phones”, but the number of people who do is clearly greater than 50% of the world’s population. Given phones shared between families and friends, and the interesting third world concept of the cellular payphone, the percentage of the world’s population that is old enough to have made a phone call and has never done so must be in the low single figures. The use of this meme by the internationally prominent seems to have finally died over the last couple of years: even someone as dim as Al Gore can figure out from his occasional views out of windows of five star hotels or between the gaps between members of his entourage on his occasional trips to the third world that something has changed, I suspect. Finance and business folk get this completely and got it long ago: fortunes have already been made selling mobile phones to people in poor countries. But the well intentioned who seldom leave rich cities other than to visit Mediterranean beaches still don’t generally get it. At best, people who see Africa as a problem to be addressed through benevolence, charity and aid have made small differences in a few places. The capitalists who have built mobile phone networks have transformed the continent utterly. The logistical networks that go with them have facilitated all kinds of other changes, too, in terms of logistics and markets. All kinds of consumer goods are available that were not before. (Many people cannot afford them on an everyday basis, but they are there, and this matters). Just as in the west, food is better, and there is more variety. There are lots of under the radar small businesses that were not there before either. Access to information and to the outside world is much greater. As it happens, my first trip to Africa was to Kenya and Tanzania, and a main aim of that trip was to climb Kilimanjaro, too. → Continue reading: Mobile phones are only part of the story in Africa |

|||||

All content on this website (including text, photographs, audio files, and any other original works), unless otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons License. |

|||||