Of course, officially speaking there was never a First Battle of Passchendaele but most of us are aware that in 1917 in the space of 3 months at the cost of 80,000 dead the British advanced from just outside Ypres to Passchendaele Ridge.

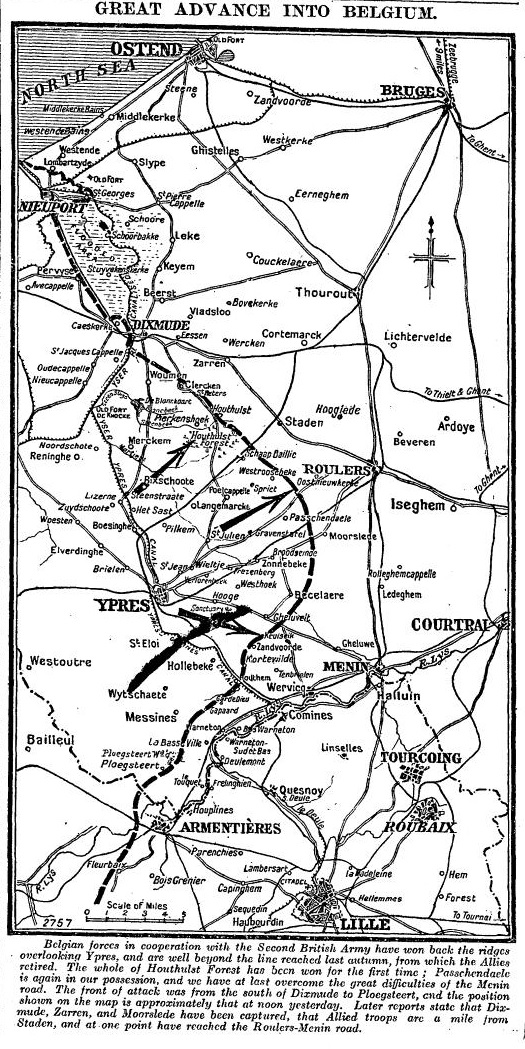

In September 1918, they – along with the Belgians(!) – did it in a day.

A day. A couple of months ago I wrote about the Battle of Amiens. I still find it astonishing. And I find this astonishing too. Because it is so difficult to explain. The British army had been battered in the Ludendorff Offensive. It had been clinging on. It had lost huge numbers of men. The sense of panic went right up to the top. And yet, when it went on the offensive itself it found it was seemingly pushing at an open door. Second Passchendaele – as I choose to call it – wasn’t even the biggest victory that week. Sure, the British Army had got a lot better at attacking. There is a clear line of progression from 1916 to 1917 and one must assume that that continued in 1918. But there is nothing to suggest this amazing series of victories.

I imagine that German morale must have suffered a catastrophic collapse. But even that doesn’t make sense. More Britons died in the Hundred Days Offensive than at First Passchendaele. The Germans might have been down but they weren’t out. At least not yet.

As I understand it, it was almost all tactical and logistical improvements. They’d finally figured out how to attack trench lines successfully, on both sides – tank spearheads, minimal initial bombardments, crawling bombardments during the actual attack, “stormtrooper” infantry tactics, sufficient artillery and shell to enable diversions, and so on, and so forth. That’s why 1918 moved so impossibly fast compared to 1915-17.

The idea that the Allied generals were a bunch of fools who just beat their heads against walls for the whole war really doesn’t hold up – they learned too slowly, to be sure, but they did learn.

For those interested in World War One, there is an excellent series on Youtube that has been exploring it on a week by week basis: The Great War. They also do videos on side conflicts, personalities and weapons of the war. The same group just started a similar series on World War Two as well.

Also worth noting that the German defences were much weaker with considerably fewer men and as the best soldiers had been combed out for “stormtrooper” units, of lower overall quality.

And the weather was good as well.

German morale had not wholly collapsed, but a lot of units were not fighting hard. It is noticeable in the “100 days” that there were far fewer German counter-attacks; and the counter attack was a core German tactical doctrine. It did require good morale though to consistently counter-attack.

And I agree that actics were more consistently skillfull by this point, but at least some of the tactics were the same as 1917.

Perhaps Haig’s strategic view that a war of attrition was necessary to get to the point where genuine breakthroughs were sustainable was in fact correct. The same applied in Normandy in 1944, over a shorter time frame sure, but also in a limited environment where Germany had very limited resources compared to their overall capacity. The casualty rates in the attrition phase of Normandy were similar to and in some cases exceeded those of WW1. The breakthrough though was more spectacular, primarily because the armies by then had far more mobility and far better communications to exploit that mobility.

I highly recommend Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History series on WW1;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALus607sH7g

Goes into fantastic detail about the challenges and approaches used on both sides.

I highly recommend Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History series on WW1;

So do I.

The article about Dr G F Nicolay on that page is interesting, too. He predicted in 1915 that the war was a terrible idea. Also the journalist is already writing about how the German people, even if they overthrow the militarist government, will need to repent by making good the evil they have wrought.

Three useful books on 1918 are:

Artillery in the Great War by Paul Strong – the development of Western Front tactics;

The Day We Won the War by Charles Messenger;

With Our Backs to the Wall by David Stevenson – a comprehensive look at both the battle and home fronts.

To alsadius’s and Ed’s comments I would add:

1) The Ludendorff offensives were a mix of Pyrrhic victories, strategic and tactical defeats which left a depleted army holding an extended and vulnerable front line;

2) The crisis brought about by the German offensives led to a unified Allied command, forced the British government to release large reserves held in the UK , and accelerated the arrival of US troops;

3) By 1918 both French and British armies had at last solved the problem of how to break into German lines and hold them against hitherto successful German counter-attacks by skilfully using their considerable material superiority;

4) As was commonly the case after failed offensives, German morale declined, especially as many troops were well aware that this was Germany’s last gasp before American intervention made victory impossible;

5) Morale was further affected by troops overrunning well-stocked Allied depots which quite undermined propaganda about the success of the U-boat campaign and implied that not just troops but civilians too were vastly better off than their semi-starved German counterparts.

The British attack at Amiens, on top of much improved defensive efforts by the Allies, came as a shock and revealed that the huge effort by Germany in the preceding months was for naught. More than half of German surrenders on the Western front came in the last three months as incessant Allied attacks exhausted outnumbered defending soldiers and destroyed German reserves.

General Gough did not do well during the Passchendaele offensive – indeed the mess of August 1917 was not just the fault of the rain (although summer rain WAS to be expected in the area, and the heavy shelling destroyed the drainage system – something that Haig was warned about, but choose to ignore the warnings), but also the fault of Gough just not being a very good infantry commander (he was a cavalry man and might have done well in the Middle East – but the Western Front was not a place where General Gough should have been). But General Plumer did do well, there were a series of tactical victories under the command of General Plumer.

However, I can see Haig’s point against Plumer (yes, for once, I can see Haig’s side of the argument). General Plumer and men like him thought in terms of tactical victories (killing Germans and taking certain positions) – Haig wanted to attain strategic military objectives, and these objectives (very valuable military objectives – I fully CONCEDE that) could not be achieved by the sort of tactical victories of General Plumer, no matter how impressive these tactical victories were.

Where I disagree with General Haig (and YES with a century of hindsight) is that I do not believe that his strategic goals for the Passchendaele offensive were achievable. In short Haig was saying “using these tactics will not gain us the strategic gains I want” – and my answer would be “the strategic objectives you want for this offensive are NOT achievable”.

We can not forget that the Passchendaele offensive was not just made up of a series of tactical victories by Plumer – the offensive went on for months, cost a vast number of British lives, and none of the strategic objectives that Haig wanted to achieve (and I admit, fully admit, that what he wanted to achieve with this offensive would have been very valuable) were achieved.

Therefore, due to the cost of men (265 thousand British soldiers killed or badly injured) and the failure to achieve the objectives, the overall offensive must be considered a failure – in spite of the important tactical victories of General Plumer from September 1917 onwards (Plumer was brought back to replace Gough in August – but spend several weeks studying and planning before launching his attack). The first of Plumer’s September attacks was a tactical success, as was the second attack (Polygon Wood) at the end of September, and battle of Broodseinde in early October 1917.

11 KMs of marshland were not work 265 thousand British casualties – but, to be fair to Haig, his objective was NOT 11 KM of marshland, he wanted a lot more than that. Unlike the Somme Offensive (where Haig does not appear to have had real military objectives) – General Haig did have real military objectives for the Passchendaele offensive, and had those objectives been achieved they would have justified the offensive. They were NOT achieved – but we say that with the benefit of a century of hindsight.

As usual there are two military questions.

“What is the military objective we are tying to take?”

And.

“How do we take that objective?”.

For the Passchendaele Offensive (unlike the Somme Offensive a year before) General Haig at least answered question number one – he DID INDEED have a valid military objective, take the coastal area, deny it to the Germans – thus partly undermining the German submarine offensive that was threatening to CRIPPLE Britain. Haig’s objective was a worthwhile one. He did not manage to answer question number two – he did not take his objective. But a lot of very worthwhile military operations do not succeed – and we (I) must be wary of hindsight.

After all, as even Colonel Barker (a severe critic of General Haig) pointed out – the original plan of Haig was NOT to smash up the drainage of this area of Flanders with a massive and prolonged artillery bombardment – Haig wanted a mass of TANKS.

Also Haig MAY (all sorts of plans were discussed) have originally wanted to attack soon after Plummer’s original attack Messines ridge (June 7th was when that attack occurred). The big gap between early June and the start of August was not good.

British industry failed to provide Haig with the mass of tanks (and the quality of tanks) Haig originally wanted (thus leading him to turn back to the idea of mass prolonged artillery bombardment), and delays and other such delayed the next stages of Passchendaele in the planning stages (for all sorts of reasons) till the end of July start of August (under Gough).

If we ignore the period under Gough (basically August 1917) and the period after Broodseinde in early October – then the Passchendaele offensive does not seem so bad – but, of course, we can NOT ignore the really bad periods of the Passchendaele offensive.

As every private (let alone General) should know – killing people is not the objective of a military campaign, killing people is the horrible thing one has to do in order to achieve the military objective. If one can achieve the objective without killing anyone at all that would be wonderful – but, sadly, normally one does have to kill people and (yes) suffer casualties (dead and maimed friends) on one’s own side.

What one has to judge is “is this a military objective for which such sacrifice is justified?” and “do we have a realistic plan that has a good chance of achieving the military objective?”

Two hundred and sixty five thousand dead or maimed British soldiers was not an acceptable price for 11 KM of marshland – but (as I state several times above) 11 KM of marshland was NOT the objective of General Haig – he did (unlike in the Somme offensive of 1916) have real military objectives (and military objectives of real value) for the Passchendaele Offensive of 1917. He just was not able to achieve them – in part because the technology and methods (such as large numbers of advanced tanks – and well organised landings on the coast as well) was just not available at the time.

Compared to General Patton and General Macarthur in the 2nd World War, Haig does indeed look utterly pathetic – but Patton and Macarthur had access to technology and methods that Haig just did not have. He could see what he wanted in his mind – but he could not reach out and grasp it, the technology and methods were just outside the reach of his hand.

Nor was their any real alterative to opposing the Germans in the First World War. This is shown by the following.

The infamous “two letters” to the Russian government (delivered as the same time – the first letter saying the Germans were declaring war because the Russians were mobilising, but the second letter saying that if the Russians changed policy the Germans would DECLARE WAR ANYWAY).

The TISSUE OF LIES that was the German Declaration of War upon France in 1914 (which even pretends the French are bombing Bavaria) – which President Poincare was right in saying was not really a declaration of war upon France, but rather a declaration of war on the very idea that there were universal and objective principles of reason and justice (as a philosopher Poincare knew that universal and objective principles of reason and justice were exactly what German academia DENIED – and he also knew that the German academic and the German political elites were joined-at-the-hip).

As for Britain – the German Ambassador to Britain Karl Max (Prince Lichnowsky) outlined various ways in which Germany could have its wars of aggression to destroy Russia and France WITHOUT having a war with Britain (the British government were desperate to avoid war – and would have grasped any good excuse to avoid getting involved, indeed Canadian ministers expressed contempt for the timid nature of the British government in 1914) – the Imperial German Government rejected the ideas of Ambassador Karl Max with total contempt. They ASSUMED there would be war with Britain – and just reasoned that they could destroy Belgium and France before we could come to their aid. Then the longer term objective of German academic “Geopolitics” (the destruction of Britain itself) could proceed, and Germany (in control of the European continent) could seek to strangle the United States in the long term and achieve the objective German academic Geopolitics (control of the world – world domination). That Prince Lichnowsky did not agree with this objective just showed that (like General Falkenhayn and his family) hopelessly “old fashioned” and “reactionary” – and unable to “free himself” from “the chains of the concepts of moral right and moral wrong” which the “modern” “Progressive” and “scientific” thinking had rejected.

So it was not just in 1939 that Britain found itself facing a ruthless enemy who had (and I will use the word) embraced EVIL and made it the basis of their policy – this was also the case in 1914 as well. The desperate desire of such men as Prime Minister Asquith and Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey for peace was doomed to failure – and only by LYING about such British ministers (and LYING about Czar Nicholas and his foreign minister as well) are apologists for Germany able to maintain their fictions.

As for the military commanders of 1917 – I hope that no one will accuse me of being an apologist for General Haig (a man who I have attacked for many years – indeed for many DECADES), but his interests were golf, horse riding and personal advancement – compare that to his opponent, General Ludendorff, a man whose interests (beliefs) contain all the basic doctrines of National Socialism, later made famous by senior private Adolf Hitler (a man who invented NOTHING – simply taking the political ideas fashionable in Germany and putting them into practice).

Paul, just would comment that although some rain could be expected in Flanders, that late summer and autumn was ahistorically wet, it rained far beyond the norm and way beyond even the pessimistic estimates of the amount expected. And it didn’t start to rain until after (I think) 9 October, and then continued almost non-stop.

Interestingly, if you compare Gough’s offensive and Plumer’s first, in terms of the casualties suffered for the ground gained, Gough was significantly more successful than Plumer. The major difference was that Gough promised a lot more and didn’t get it; Plumer promised a lot less and did achieve what he said he would. And had Gough had a better understanding of the tactical needs – for example the need to attack or at least neutralise the area that Plumer later attacked before his lunge out of the salient, he might have done much better as the troops were freshest and the ground less damaged even though in neither attack was the ground particularly muddy. Haig’s fault with Gough is that although he apparently pointed out the tactical demands, he did not enforce them and let Gough have his head, almost certainly incorrectly.

One could also point out that Haig didn’t need an absolute breakthrough, if he could bring the rail centre of Roulers under direct artillery fire from the high ground along the ridge with sufficient numbers of guns, the German occupied territory between that point and the Dutch border was probably untenable, forcing a general withdrawal at that point.

One final point, one of the most important effects of the unified command was that it placed upon the French a commitment to support the British with reserves, and it removed from defeatist Petain the opportunity to abandon the join with the British in order to cover the possible German advance on Paris from the Amiens area. Petain was too strategically short sighted to see that unless the Germans could overwhelm the allied armies, the only way they could win was to defeat them in detail separately. Thus allowing the Germans to penetrate between the British and French forces was to give the Germans their only real chance to win. To his credit Foch could see that, but so could Haig, but an CinC had to be French because of their numerical superiority, so luckily it was Foch not Petain.