Daniel Ortega, remember him?

Ortega was one of the leaders of the Nicaraguan Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) that overthrew the dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979, thus ending 43 years of rule of Nicaragua by the Somoza dynasty.

For a while Sandinista rule in Nicaragua was popular at home and admired worldwide. A often-repeated line from left wing sources was that its success represented “the threat of a good example”, the good example being of a country thriving despite the opposition of the United States, which had supported Somoza, as it did many right-wing dictators in Latin America.

The admirers included teenage me. Not that I followed every twist and turn of Nicaragua’s politics, but, at first, it all sounded good. Land reform. Education. Healthcare. If I had known then what I know now “price fixing for commodities of basic necessity” might have told me what was coming, but I did not know then what I know now.

Several years went by and a few discordant notes started to spoil the chorus of praise. The forcible ejection from their ancestral lands of the Miskito Indigenous people (at that time everyone, even the Guardian, called them “the Miskito Indians”) was one ugly incident that I remember noticing. This Time article from 1983, “Nicaragua: New Regime, Old Methods” gives many other examples of Sandinista human rights abuses.

That said, the Sandinista National Liberation Front of that era under the leadership of Daniel Ortega still had enough decency left to hold an election and, having lost it, leave.

I will spare you a blow by blow account of Nicaraguan history from 1990 to the present day. You can read Wikipedia as well as I can. Suffice to say that half a lifetime later the reference books once again list the Sandinista National Liberation Front as the ruling party of Nicaragua and Daniel Ortega as its leader, and this time he has no plans to ever leave.

“Nicaragua: Ortega and wife to assume absolute power after changes approved”, the Guardian sorrowfully reports.

The Geneva-based UN human rights office in its annual report on Nicaragua warned in September of a “serious” deterioration in human rights under Ortega.

The report cited violations such as arbitrary arrests of opponents, torture, ill-treatment in detention, increased violence against Indigenous people and attacks on religious freedom.

The revised constitution will define Nicaragua as a “revolutionary” and socialist state and include the red-and-black flag of the FSLN – a guerrilla group-turned political party that overthrew a US-backed dictator in 1979 – among its national symbols.

*

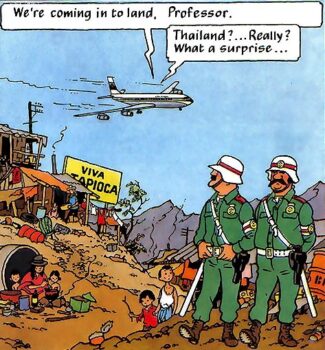

One of the Tintin books – remind me which – starts and ends with a picture of a couple of thuggish cops patrolling a shanty town. The only significant difference between the two scenes is that the party symbol on the police uniforms has changed.

Update: Thank you JJM, who supplied the name of the book. It was Tintin and the Picaros. ¡Viva [Tapioca / Alcázar] !

I don’t recall the illustrations but your description suggests it may have been the first ever book “TinTin in the land of the Soviets”.

In a “revolutionary state”, isn’t there always an implied duty to assassinate the leader?

Human rights violations? By a recipient of the Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights, surely not.

IIRC in 1990 every UK daily and Sunday newspaper, plus The New Statesman and The Economist called the Nicaraguan election incorrectly; only The Spectator successfully predicted the actual result.

“One of the Tintin books – remind me which – starts and ends with a picture of a couple of thuggish cops patrolling a shanty town.”

It was Tintin et les Picaros. ¡Viva Alcázar!

Per JJM, off the top of my head, there was a running theme in Tintin’s stories of the good guy, General Alcázar, who regularly took power in a mythical Central American country, capital San Theodos (?), and his bitter and sinister rival General Tapioca (at least called that in English). There is one book where there are coups and counter-coups with Bolivian-style rapidity and even the firing squads change sides instantly when told of the latest coup. Eventually, Tintin makes Alcázar promise, after his latest counter-coup, not to shoot Tapioca. The two Generals then lament the falling standards and the attitudes of the young generation. I suspect that in Nicaragua that Tapioca has assumed power now for good. The only line in the ledger to his credit is his opposition to lockdowns and the Covid Terror, even if, like in a maths test, his working was not correct, his answer was.

The only silver linings are:

1. Like Thor, he cannot defeat old age or time.

2. President Milei – Prester John – is setting a powerful counter-example in Argentina, which might spread.

Ortega learned his lesson: holding elections was no guarantee of perpetual authoritarian rule.

I worked in Nicaragua twice, the first time on the pacific coast in an old Russian built power plant, and later on at two power facilities in Managua. I found the citizens I interacted with to be entirely admirable. All the plant workers were dressed in a manner that would pass any military inspection. Their homes may be cinder block walls with no windows or doors, and bare lightbulbs hanging from the ceilings, but the yards were swept clean, there were plantain plants tended inside the enclosures, and the children waiting for the school bus were impeccably dressed in uniforms. One day, I was wiring temperature sensors leads into the three data input cards of a data logger at a table on the steam turbine deck of the oil boiler power plant in the capital, and my engineer came up to me, laughing as he did so. I asked him what was so funny; he pointed behind me. I turned around, and there were 14 plant personnel intently watching me work, fascinated by our equipment and eager to learn. An admirable people afflicted with horrible governments.

Mr Ed:

Tapioca and Alcázar first appeared in L’Oreille cassée (“The Broken Ear”) way back in the late 1930s I believe. The fictional country was San Theodoros, a stand in for a Central or Latin American republic.

I’ve been a tintinophile since I was a kid!

@Mr Ed

The only silver linings are:

…

2. President Milei – Prester John – is setting a powerful counter-example in Argentina, which might spread.

I think it is deeply sad that not too long ago it was the United States that was that shining city on a hill, and before that Britain set a standard for freedom that many aspired to. Now they are quickly turning into examples of what not to do. The inspirational “rights of the Englishman” has turned from a call for freedom everywhere to a cautionary tale.

However, I think there is a third silver found in the great comment by Bruce Abbott. His experience of the Nicaraguan people suggests that they are a very good, hard working people and perhaps that dormant giant will wake up and take back what is theirs. If so I wish them well. Without these oppressive governments and massive gang problems Central America could be a powerhouse.

Mr Ed – quite so. Although Uruguay has just chosen to go the other way, the path of Nicaragua, Brazil and Venezuela.

Indeed it is worse in a way – as the election in Uruguay appears to have been straight, unlike the rigged elections of Brazil and Venezuela, so the people of Uruguay have freely chosen to wreak their own country.

As for the socialists in Nicaragua – they left office in 1990 because the United States put very strong pressure upon them to do so, and because the Soviet Union (their patron) was collapsing in 1990.

I will say one thing for the socialist dictator of Nicaragua – he did not have a Covid lockdown. But then neither did Uruguay – and that moderate conservative government has just been voted out of office.

Decency had nothing to do with it. The Sandinistas were under heavy military pressure from the US-backed Contra guerrillas. They held the election to gain “legitimacy” with the “international community” and make the US back off.

To achieve this, the election had to be real, with actual free, secret voting. They had to let the opposition organize and campaign, especially as the opposition candidate was the widow of the man whose murder by Somoza had triggered his downfall. They also accepted a cohort of foreign election monitors.

But they thought that with control of all state resources, the prestige of “the revolution”, and extensive harassment and intimidation of the opposition by their goons (“turbas divinas”), they would eke out a plausible majority.

They were wrong – and the result was so clear that even the mostly-sympathetic foreign monitors could see it. At that point, the Sandinistas had to yield power, or else face possible US invasion.

As I wrote above, it wasn’t “decency”. It was at de facto gunpoint. They couldn’t just rule by force, and their attempt to scam legitimacy backfired.

BTW, as the Sandinistas left the government, they looted it of anything portable: money, vehicles, weapons, office equipment, even furniture.

I note that the American government has sanctions against both Nicaragua and Venezuela is response to their rigged elections – but there are no sanctions against the government of Brazil, indeed the “G20” and so on trot along there for conferences, even though the Brazilian election was also rigged.

“Ah but Paul, you do not understand – Brazil is an IMPORTANT country”.