We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

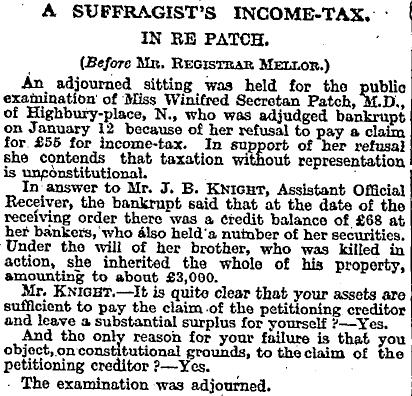

#imwithher  The Times 28 February 1917 p4 And no representation without (net) taxation one might add.

I did some searching to see what happened in this case but to no avail. I presume the state got its money in the end. As to the good lady herself there seems to be some sort of medical prize in her name.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|

But the good Doctor did have representation, the Rt. Hon. or Hon. Member for her patch of Highbury, she just could not vote for her representative, like an English, Great British or UK Peer at that time, as with infants and lunatics.

Fair point Mr. Ed, but I’ve noticed over the years that the buggers take increasingly more notice of you depending upon your ability to stymie their election chances.

Thus a child/lunatic/woman in 1917 would get less attention than a voter whereas a voter would get less attention than a member of their constituency panel (overseeing reselections, etc.)

I still agree that the refusal of Miss Patch to pay income tax without the ability to vote was a reasonable protest to make, but equally the His Majesty’s Inspectors of Inland Revenue also were right to pursue her through the court and presumably take recovery action.

The law either applies to all or to none.

But her point – that she was denied the vote because she was a woman – was the same as yours, wasn’t it?

(P.S. Her good silver had been seized prior to her hearing. It was sold to pay the resulting judgment. This was a yearly occurrence for her.)

Thanks for that bobby b. I had no idea her protest had been going on for so long.

#imnot. While on a personal level she might not had been enthusiastic about paying taxes (duh), as a suffragist she was effectively promoting the current situation, where just because I may vote, I must pay taxes. I am not thankful for that.

The suffragettes were the small minority, the suffragists the large majority, of those women who campaigned for the vote in the UK in the Edwardian era. The suffragettes believed in law-breaking. The suffragists objected, both on principle (they argued that in a country with free speech and similar personal rights, the cause both could and should be advanced by legal means) and from a practical point of view. They felt some of the wild public antics of the suffragettes hurt the public perception of how calm and competent the average woman voter would be. One suffragette threw a bomb that failed to go off, thus doing nothing for public perception of their self-restraint or their competence (the anarchists’ bombs usually did go off). Quite a few suffragettes chained themselves to railings in places that ensured they would be manhandled by male policemen; this tended to prompt less-than-affirming thoughts about what was going on with them. The suffragette who threw herself under the riders of the grand national threatened horses as much as men, and many women then as now cared for horses. Etc.

During the war, the suffragettes themselves split on the issue. Some argued that their cause was unlikely to prosper under the Kaiser’s rule, therefore they should support the war and resume any law-breaking tactics of their campaign after the war (if still needed). Others (like the woman in the story, one presumes), continued to see the UK’s government as their proper opponent. She does not indulge any wild antics but she does refuse to pay taxes on the £3000 inherited from her brother “who died in action”, so, apparently, she sees the war as not to be be funded while her freedoms (that it protects) are incomplete.

The war changed things. In 1912, women who opposed both suffragettes and suffragists proposed a referendum of women on whether women should vote. It was opposed by the suffragettes and suffragists; it’s clear that all groups were making the same guess as to what the result would be. In 1918, after years of women working in factories to make the weapons men used on the battlefield, a great many minds had changed. (Examples: in 1912, a conservative army officer like Sir Douglas Haig would have been unusual if he had supported women’s suffrage. In 1917, in one of his addresses to his men, Haig praised the courage of women dealing with a fire in a munitions factory a few months earlier, clearly relating it to their having earned a voice. One MP contrasted his pre-war “irritation” at suffragette demonstrations with his during-war value of women whom he found himself praising and thanking at every turn.)

The intellectuals’ version of this history is that the suffragettes won their sisters the vote, the suffragists deserve to be airbrushed out of history and the war was nothing to do with it. A few decades back, the beeb put on a series guided by exactly that viewpoint, and in their comments section – ah, sorry, their letters page (it was indeed a few decades ago 🙂 ) – the scriptwriter replied “you are wrong” to the women who wrote in to say they won themselves the vote during the war. This is one of PC’s many “rewrite it the way it should have been, and then teach that” actions.

Meanwhile, the issue of the OP’s story is one that also faces us. I pay my taxes to a government that maintains Blair’s reduction of my free speech rights – not, be it noted, a new right I want but an actual customary right I had and want back. As against that, if I look at how far the current government actually enforces the reduction, it’s excessive to compare my situation with the OP case; a fairer analogy might be with e.g. women’s votes having equally decided all issues but now not applying to some issues. (BTW, before 1832, a few women did vote in some constituencies. Each constituency had its own specific regulations, so, depending how the property qualification was in fact phrased, if a woman owned 20 shares in the local tin mine and that authorised voting, that woman could vote, and sometimes did. Electoral agents kept track of women who voted, to advise their candidates to woo them – electorally speaking 🙂 – as various letters from the 1700s show. IIRC, estimates are that maybe 1% of the voting population was female. The 1832 act made things uniform, so for a few it was withdrawal of a customary right.)

Unlike the woman in the OP story, who had a war to think about and good reason to expect her cause to win when/if the war was, I have no such actual hot war. I have a Brexit I hope to see start before end-March and be carried through to victory – I have some hopes the free-speech situation will then improve. But while my lessened free speech has some EU aspects, mostly it’s a symptom of a slow, creeping war between the west and its enemies, foreign and domestic and were-foreign-but-are-now-domestic. I have as much cause as she did in (I’m guessing) 1917 to expect victory in the one to mean victory in the other.

So if the law says all females over the age of 18 must have their right ear cut off, this should equally apply to all males above that age?

This is one of those instances where the distinction between law and legislation must be made. If taxation is legalized theft (and no, I’m not saying that it necessarily is – depends how one defines and applies it), then it is not The Law, it is mere legislation, and so there is no point in talking about ‘equality before the law’.

Niall Kilmartin (February 28, 2017 at 10:16 am): “I have as much cause as she did in (I’m guessing) 1917 to expect victory in the one to mean victory in the other.”

I wrote a long post, checked it carefully to remove all the poor phrasings and typos – and now realise I wrote the last line, making the key point, confusingly. 🙂 So instead, here’s the same point briefly:

– If I survived a prosecution of something I said, that would contribute my tiny morsel of expressed support to the war whose victory will also restore my free speech.

– If she had survived the OP prosecution, that would have withheld her tiny morcel of financial support from the war whose victory also gave her the vote.

(So now you can skip reading my long post. 🙂 )

The argument has certainly been made Alisa and by greater minds than I (for example Plato’s dialogue Minos)

I find myself well suited to the natural laws of man, but I am often at odds with the “rules and regulations” drawn up by legislatures pretending to be laws. They just aren’t.

I therefore (by and large), hold them in contempt. I avoid, evade, frustrate and ignore them when I can and only obey them when the only alternative is civil or criminal proceedings.

I doubt that I am alone in this.

I would like to thank Niall for that wonderfully informative comment. I was not aware of calls for a referendum of women. It does not seem to have been mentioned in The Times although another one (Ireland?) was. Also, if the argument against woman suffrage is that they are not up to the job of deciding on issues of the state how could an anti-suffragist accept the result? Also, which women would have been allowed to vote: all, or those with the same qualifications that applied to men? And, this would have been quite an administrative task.

I find it a strain to have sympathy with anyone whose argument is more ‘I want a say in taxation and spending.‘ rather than ‘I should not be taxed, particularly when I am not even permitted to have a say in who decides taxation and spending‘.

Thanks are definitely due to Niall Kilmartin for his longish post at February 28, 2017 at 10:16am.

I was particularly pleased to see the bit on the UK women’s franchise being explicitly withdrawn by the Reform Act of 1832. This is a fact that I only became aware of recently – IMHO it is important in the history of UK electoral reform.

Best regards

I am somewhat surprised to find someone using the pseudonym John Galt arguing in favour of Plato.

Though my own objection to Plato’s philosophy (especially the concept of Philosopher-Kings) is almost entirely down to Karl Popper (eg The Open Society and Its Enemies), I have found the following on Ayn Rand and Plato.

I also read that the attribution of Minos to Plato is at least somewhat disputed – which, if correct, might help explain things otherwise conflicted.

Best regards

How so? You may recall that the ‘snoopers charter’ was declared unlawful by the ECJ (as far as I am aware this verdict is being ignored for all practical purposes). I have no illusions about the UK’s attachment to free speech. Us Whigs are a very small minority. Many of our English rights are protected better elsewhere, including in Europe.

…or on the issue of the use of explosives, for that matter… 🙁

Yep.

Indeed. I think ‘one woman, one vote’ would have served this country better in the last 70 years. The woman in particular being Queen Elizabeth II.

I think there’s a conflation of arguments about taxation and representation here. We do not know the personal view of the lady refusing to pay taxes due to lack of representation on taxation, since this is not mentioned in the sources. It could be she opposed this generally, but was not making an issue of this as her major concern was to be given equal representation (it would certainly have confused her stance). So the suggestion that we cannot support her stance because she was accepting taxation (during a war which had to be funded remember) is hardly valid. Even if we agree taxation is legal theft, then that does not mean that we can criticise someone for saying they will only give in to the pressure of legal theft if they have the same right as others who also give in to that pressure, as clearly having to accede to legal theft without any ability to be involved in the decision making around legal theft is worse than having to accede to legal theft whilst having the opprotunity to change things through your vote.

So, bluntly, it is a better situation to have the right to vote to end the legal theft that you suffer from than to not have this right. And in this respect, I agree with the original post.

Now we have some women who say that men have no right to take part in the debate on abortion, but they happily accept NHS funding for the operations, much of which is taxed from men’s wages.

I was not arguing in favour of Plato, far from it, I was merely pointing out that the argument between natural law and legislative fiat* has been going on since antiquity.

The vast majority of legislation is rent-seeking, either the lobbying of government by 3rd parties or the abuse of government power by politicians and civil servants.

We would be far better off scrapping the entirety of parliamentary legislation and telling the magistracy / judiciary to ‘apply common law in all cases’ then allowing the traditional appeals system to sort out any issues.

But that’s a bit of a thread hijack so…

* – Which amounts to “Do what I say or I will bash you”

So a female variant of Sir Pterry Pratchett’s “One Man, One Vote” approach…

Watchman, I’m not sure I agree that it is worse. By protesting against a minor part (taxation without representation) of a greater evil (taxation) you, perversely, grant authority to the greater evil. Sure, I accept that the woman in question may not have viewed taxation as being the greater of the two, but, given the views that I have on these matters, I cannot look at her actions in a charitable light.

Indeed John G, the denizens of Ankh-Morpork don’t know (I first wrote ‘didn’t know’ but then I realised that Discworld is in a parallell universe) how lucky they are.

To be fair though, taxation at the time was trivial compared to modern standards. Or so I suppose.

Funnily enough, I was having a few beers Monday night in the local boozer here in Penang and had a reasonably robust exchange of views on the point that “The best thing for the French* would be to restore absolute monarchy in France and abolish democracy altogether“.

In the end we agreed but couldn’t decide who to put on the French throne, the current line of pretenders all being contaminated with ‘the French disease’.

* – If you exclude the option of total extermination 😆

Niall, thanks so much for your comment on the real history of the suffragettes, suffragists, the women not included in either group, and WW I’s effect in making it clear that women had earned the right to vote. I certainly didn’t know all that.

Peter T,

I am not sure I see exclusion from government as a lesser evil than taxation to be honest. Taxation is morally questionable, fine, but having a system where only a certain subset of adults (of sound mind etc – and yes, I recognise the issues all that brings) can participate in government is far worse. Should the government not be imposing taxation or other impositions, then maybe taxation would be the greater evil, but this was not about choosing taxation or representation, but simply seeking to rectify one of the two wrongs – it is entirely possible that those seeking universal sufferage may have approved of taxation (actually I doubt they approved of anything universally, being a diverse bunch) but that does not mean the justice of the original case should not be recognised.

I feel this taxation is more important than representation line is similiar to the left’s equality is more important than freedom of speech issues: it takes a particular hobby horse of the particular thinking prevalent in that group, and somehow makes it more important than an important aspect of freedom – in this case, all the people being able to participate in government. If a freedom is important enough that both us and the statist left agree on it, it is unlikely that it can actually be trumped in importance by one of our particular issues.

As to the idea that Queen Elizabeth II would have been a good absolute ruler, it might work, but please remember that the one vote would pass to the next monarch, last seen suggesting sterlising grey squirrels with nutella… After all, in Ankh-Morpok a plot to remove the Patrician was only defeated by journalists (you can tell this is not the real world, as journalists here plot to depose leaders…) and the Patricianship had previously been held by a number of manifestly self-interested or incompenent figures – basically Lord Vetenari was a blip, and there appeared (I think the past tense is appropriate for Discworld now it is no longer a ‘living’ world) to be no succession planning to ensure the stable regime continued, as power had corrupted the guild leaders who were meant to maintain the balance, and perhaps most worrying the head of the police force was the next most senior figure in government. And yes, I do know too much about Discworld…

Permit me to join the chorus praising Niall Kilmartin’s lengthy post about the history of women’s suffrage in Britain. I wasn’t previously aware of much of that.

A quick question about the article posted: it contains no reference to any year. How do we know this was 1917?

Er, Laird, the date is in the caption: 28 February 1917.

Queen Elizabeth II is always a good role model when discussing absolute monarchy and Chuckles Buggerlugs III is always a good argument against it.

In Jack Pullman’s classic production of “I CLAVDIVS”, Claudius was pondering why both his ancestors, uncles and nephews varied so greatly from the heroic to the downright insane.

Then, his friend Herod reminded him of an old saying :

I suspect this is also true of the House of Windsor…and Chuckles is very, very bad.

Patrick, perhaps this is some quirk of my computer, but I see no “caption”. The title of your post is #imwithher, and beneath the Twitter (etc) icons is the date of posting (February 28th, 2017), but I see nothing else. What do you mean by “caption”? Something in the copied article itself? (No date there.)

Ok, I found it. I opened this post on my Android phone and could see the “caption” just beneath the article. But it is illegible on a PC when opened using Google Chrome. So then I swiped the cursor over the screen just below the picture and there it was. The “caption” is in blue font on the blue background and so can’t be seen normally. Perhaps the webmaster can do something about the font color.

I’ll add another vote for Watchman’s point.

There are many evils within government that we can choose to oppose or not, but without the right to vote in a democracy, you have no voice with which to do so.

John Galt makes the point that “We would be far better off scrapping the entirety of parliamentary legislation . . . ” in his comment about “law versus legislation”, but he’s assuming membership in that “we” as a starting point. Dr. Patch sought to be allowed to vote – to be one of that “we” that decides such things. That’s a far more basic fight than a fight about any one specific issue about our governance.

bobby b:

Agree. And as recent votes in Britain and here show, the voters can vote to change things, if they get riled up enough or if one candidate is more awful than the flesh of most can bear. Of course, in both cases it remains to be seen if, or how far, the changes for which they voted will be made.

. . .

Rant: Who in the world thinks that the system of hereditary monarchy, or of “absolute monarchy” (totalitarian dictatorship), has a good track record “because after all the kiddies are trained to the office.” Good grief! Historical counterexamples abound! For a current example of the worst of both worlds, consider our pals the Kims of NORK. Note also that those on the throne or in line for it risk unnaturally short life-spans.

.

Furthermore, no Constitution will save things unless the PTB buy into its strictures.

/endrant :>)

One odd thing is that (I believe) that female property tax (“rates”) payers did have the vote – both for Poor Law Guardians (from the Act of 1834) and for local councils (the Act of 1835).

But Parliament was different – even for women who paid income tax.

In some American States in the 18th century (for example New Jersey) female taxpayers had the vote – but the Democrats took it away.

Wyoming was the first State to give the vote back – as a Territory in the 1860s, then as a State from 1890.

As for taxation and representation.

As Gough pointed out in his little book on John Locke (still the best work on John Locke), Locke is slippery when it comes to the transition from individual consent to majority consent (there is a jump – without proper argument).

There had been nobles in the Middle Ages who are argued they could not be taxed without their INDVIDUAL consent. That the Crown could call up their sword arm – but not their money. And there arguments were sometimes presented to include ordinary people (not just nobles).

The only real counter argument to this is “it does not work – it leads to the Commonwealth of Poland”.

If universal consent (even among nobles) is demanded someone will always object. And the Realm will be left open to its enemies.

It takes only one side (not two) to make a conflict.

As Belgium found out in 1914.

Laird, like youI rather missed the 100-years-earlier way of knowing the date. Instead I reasoned that it must be 1915 through 1917, since her brother was “killed in action last year” and in 1918 or 1919 she’d have the vote or at least know it was on the way. I guessed 1917 as most likely, since British war dead in 1916 were much higher than the two prior years.

PeterT (February 28, 2017 at 12:30 pm), I have (only) ‘some hopes’ of post-Brexit free speech improvement, or at least of lesser danger things will get even worse because the EU is even more enamoured of “hate speech” laws then we are. The Erdogan poetry competition happened here, and was inspired by events in Germany. As Mr Ed IIRC put it:

A vain president lives on the Bosphorus.

Any satire makes him feel quite phosphorus.

Said Frau Merkel, “Fine sue;

As regards the EU,

Ending free speech will not be a loss for us.”

To all who said thanks for my comment, you’re most welcome.

pete (February 28, 2017 at 1:35 pm), the women who proposed a vote on whether women should vote did not think women were stupid. They believed in a society with certain divisions of responsibility. The role of women in the war persuaded them their idea was wrong.

On the question of monarchy v. republic, the First World War was a pretty good test. The monarchies: Germany, Austria, Russia lost. The republics: Britain, France, Italy, America won. I am not quite sure how to characterise Serbia and Turkey and far from sure whether to describe Serbia as a winner or a loser.

I’m not convinced absolute monarchy would be worse on average than democracy. Although as the Kim/Targaryen example shows the outliers are more extreme (and I think sterilising squirrells with Nutella is probably a less harmful policy than most – although of course Charles might also turn off the electricity grid over night). The benefit is that the monarch doesn’t have to pander to specialist interest groups (he does have to pander to the population at large, and those that could actually threaten him – which I’m guessing doesn’t include the equal-access-to-toilets-for-transexuals lobby and their ilk). The nature of our current democracy is that the machinery of government gets captured by such people (‘activists’). However, direct democracy would be a better solution than absolute monarchy – or maybe a combination would work well.

I still find the ‘no tax without representation’ unconvincing. I have the vote but I don’t have representation – EU referendum being the only exception in my life.

Judging by the trajectory of the western world since women were given the vote, it might be pinpointed as the moment when we began our decline. Women seem overwhelmingly drawn to the soft, smothering embrace of socialism and nanny state government in a way men simply are not. I would suggest that after a major catastrophe that broke any form of civil society, women would not get the vote again so long as memories of what they did with it still exist. I apologise to those women here and elsewhere who vote on grounds of liberty, I mean to speak only as a general proposition.

Last night I was watching my DVD of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena in which Henry VIII has his missus Anne Boleyn topped, (along with a few of her friends and relatives), so he can marry Jane Seymour. Tonight I might watch my copy of his Maria Stuarda in which the daughter of Henry and Anne, Elizabeth, has her cousin murdered for being catholic, (and threatening her throne).

Absolute monarchy wouldn’t be too bad if they restricted themselves to knocking off relatives and spouses, but it never stops there, does it**.

Apparently the Italians didn’t get the message either since a few decades after Donizetti wrote the operas, they were going around scribbling VIVA VERDI* on the walls and look where that ended up.

*Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia. There is some controversy amongst opera hisorians as to whether Verdi’s greatest contribution to the Risorgimento was the occasional patriotic anthem he smuggled into his operas, (va pensiero or patria oppressa for instance), or as a piece of acronymic graffiti.

** Who mentioned Lady Di?

I am happy to see that Patrick

(a) avoids the loaded and deceitful word “democracy” and

(b) uses the word “republic” in the old-fashioned way, i.e. takes constitutional “monarchies” to be republics and not true monarchies.

Not sure that ww1 is the best test, but it beats any test that Mencius Moldbug is likely to offer.

Not so: in the UK before Blair, and in France (at least until recently), women tend(ed) to vote more conservatively than men. Presumably, that is because “the left” in the UK and France has historically been associated with blue-collar workers, few of whom are women.

(I admit that French conservatives have traditionally offered something rather close to a nanny state.)

See also the last few pages of chapter 8 of The Road to Serfdom. (Why am i always the one who has to bring it up??)

Patrick Crozier (March 1, 2017 at 9:24 am): Hannah Arendt (in “On Revolution” IIRC) argues that the violence of modern world war means no regime could survive losing one and therefore she argues that post-defeat revolution is not a diagnostic test. The view will bear debate; I mention it as a point, not an unarguable rebuttal.

Mr Black (March 1, 2017 at 11:25 am): the enfranchisement of women in Britain led to left-wing complaints about their tendency to vote Tory. The “relative barbarism of women” (I quote H.G. Wells) was seen as an obstacle to the advance of socialism. (In Well’s novel ‘Mr Kipps’, the working-class heroine’s distaste for the word socialism is Wells making the same point more politely.) In the UK at least, do not mistake some current poll for an eternal innate gender-related voting preference. The Tories had the first female MP and the first female prime minister (and now the second). When I was a lad, before the days of quotas, their female membership (both numbers and ratio) effortlessly outpaced Labour’s.

As Natalie has pointed out, the French Gaulists were the only western party to have 50% female membership before the time of quotas and PC pressure. (It seems General de Gaulle was very popular with ladies of a certain age in France in the early 60s, but they could also justify their choice, relative to his rivals, on robust logical grounds.)

I think that currently female support for the Conservatives again outstrips that for Labour in the UK. If only because that seems to apply to almost every group imaginable (Labout has a leader that only 53% of party members think would make the best prime minister…).

Anyway, surely this debate about female support is a bit silly, since females are all individuals, and can probably make up their own minds on things without having to have reference to their gender (if not, that decision to give them the vote in 1919 was a bit silly…). Men or women may vote in particular patterns, and we may be able to construct sociological explanations of why this would be, but frankly each person makes their own choice on their own grounds – my wife has in moments when she had no strong opinion voted on the ground that the candidate had the best surname for example (she tries to always vote but doesn’t necessarily engage with the issues). I am hoping that is fairly unique, and unrelated to gender. But the fact that 65% of women voted for George Clooney as President in 2020 (you heard it here first) should simply reflect the fact that there was 102,050,000 reasons to vote for him that were raised at independently by people who happened to be female, and should not be explained by the an assumption that all females vote in the same way. We’re in danger of walking the road of identity politics otherwise, even if there is a temptation to assume gender stereotypes affected people’s decision to vote for a manifestly idiotic candidate. And we’re hopefully better than that?

Just as an aside, despite her age, I’d still consider eliminating a few interfering busybodies in order to get my hands on Jane Seymour.

I’ll be in my bunk.

Just for Bod:- Anna Bolena: Netrebko – Garanca

Anna Netrebko and Elina Garanca are two of the reasons I like to get my history from Opera.

Getting back to the OP:

There is something to be said for that: it is only fair that only taxpayers have a say on how tax money is spent; and of course, the more tax you pay, the more of a say you should have. (Not necessarily in a linear relationship.)

Besides, it is a negative-feedback system: people who pay more taxes can very well vote for lower taxes for themselves and higher taxes for everybody else — but then, they decrease their own political power.

And yet, in such a system, checks+balances are needed to ensure that tax money is not spent in ways that go against the natural (Lockean) rights of non-payers. As an extreme example: Poles did not pay for the Wehrmacht, but that does not make it right for the Wehrmacht to invade Poland.

Note also that whoever makes the laws, also decides what constitutes a tax. The richest taxpayers could very well decide that only payment of income taxes qualify people for representation; then proceed to lower income tax rates to 1% and raise VAT to 40%. Or they could reinstate serfdom, a tax by any other name.

So i have an immodest proposal for constitutional reform, inspired by Glenn Reynolds’ idea of a Chamber of Repeal: taxpayers get to vote for the Legislative Chamber (which makes laws, and can also repeal them), and everybody (including taxpayers) gets to vote for the Chamber of Repeal (which can only veto or repeal laws). Of course, Poles still would not get to vote on what the Wehrmacht does, but it’s a step forward.

Patrick Crozier@ February 28, 2017 at 7:50 pm:

And the caption is in tiny dark grey letters on the dark blue background…

It needs to be better formatted, I think.

It has been suggested that Miss Patch was withholding her financial support from the war in which her brother had died.

It seems possible that Miss Patch subscribed to the British government’s War Loans. Such voluntary support would be compatible with her stand against “taxation without representation”.

An aside: “but frankly each person makes their own choice on their own grounds.” Once again the plural pronoun with a singular referent rears its ugly head! William H. Stoddard would approve.

Well, I don’t.

Rich Rostrom (March 1, 2017 at 7:45 pm), “it seems possible…”. It is possible but the text makes no suggestion of it, so Occam’s razor suggests we discuss the case without it. In any case, war loans were paid back (eventually! – my parents had some WWII ones which I was quite old enough to recall being paid back and I’m not that old; inflation had of course vastly reduced their value – WWI loans did not suffer from this). “It is not often that a man will be content to have a present made him when he expected payment of a debt.” (Dr Johnson). Loans are not equivalent to taxation even if the amounts were the same, except insofar as they’re not paid back, either literally or because the government converts them to taxes via high inflation.

As regards no taxation without representation, the immediate question in the west today is surely the converse: representation without taxation (but with receiving benefit from it).

If anyone is interested in more details of Dr. Patch’s fight, the website The Picket Line has gathered as many snippets as could be found concerning same. (The link is to a Google search that brings up articles in The Picket Line.)

In one of her court appearances, Dr. Patch noted the following: “It is to the British Constitution that the British Empire owes its place among the leading nations of the world, and it is the duty of her children to whom her honour is dear to keep her true to those principles. I was a tax resister before the outbreak of the war. The political truce with the Government was tacitly accepted by suffragists, and this would have prevented me from beginning tax resistance after war broke out. I have paid no taxes for many years, and it is a breach of faith of the Government to have just started proceedings against me now. By taking my money which is at my bank you only prevent me from putting it into War Loan, as I intended to do.”

The Suffragists made a point of regularly offering to pay contested tax monies into any War Charity the government might designate, but their offer was always refused. The government had been chasing after them for taxes for years prior to the war, and had entered into a suspension of efforts with them because their cause was getting too much public notice, but when the war started, the government, apparently feeling that tax resistance that could be labeled as an antiwar effort might not be so popular, resumed its efforts. The suffragists, not wishing to be portrayed as traitors in a time of war, offered to pay their tax bills directly into the war effort, thus defusing the government’s attempt.

At one meeting of suffragists concerning Dr. Patch’s travails, supporters said the following:

“Mrs. Despard, in the course of her speech, said that the Woman Suffragists were going to adopt measures of coercion towards the Government. They were going to “stop the traffic.” Mr. Laurence Houseman took up the phrase. He said, “Stop the traffic, and you have found the solution of the situation. Bad government makes government expensive.” He spoke of the spirit of liberty which is latent in every human being — the spirit of liberty which is always roused to its fullest force under tyrannical oppression. That spirit was awake in the women who are fighting for the Franchise to-day. He thought that most of the men of this country did not realise the spirit of that fight because they had come by their own votes too easily. They had practically been born to the Vote. They had come into it too long after their fathers’ fight for it to feel its true basis of liberty. He remarked that wherever Mrs. Despard went to-day the Government became an object of ridicule. She ought to be in prison, as she had refused to pay the Imperial taxes, but they were afraid to put her there — (laughter and cheers) — and she would not go to prison because she was more logical than the Government. If they gave her representation she would agree to taxation — the two must go together.”

It was an interesting struggle.

Thank you Niall and Bobby for the very informative comments. To me this is a fascinating subject, and the more I learn about it, the more fascinating I find it.

Still, my mind has not been changed regarding the effort to give women the right to vote in general, and connecting that effort to taxation in particular – at least when it concerns taxation at the national level: in my mind, saying that at that level a voter has any significant say in how his or her tax money is spent borders on wishful thinking. What that voter does have some say in, it is how the taxes paid by the rest of the population are spent – and I hope there are better ways to justify universal suffrage.

The larger the constituency, the less legitimate taxation becomes. At the local level one can at least talk about community, where at least some residents know some others, are connected to each other by some common interests other than national defense, and can directly influence the opinions of others on local policies, including taxes, and negotiate such policies based on such common interests. Of course it ain’t always pretty, but at least it is in some way based on real opinions and real interests of real people.

The above also applies to voting, and that is why, for example, in the US we don’t elect Presidents based on popular vote.

Alisa (March 2, 2017 at 9:19 am), I sort of agree with your comment above but with some caveats/concerns. “The larger the constituency, the less legitimate taxation becomes.” You can tell if, in the next paragraph, we’re actually agreeing – if your “the larger the constituency” means precisely the UK’s meaning of undifferentiated winner-takes-all constituency as against some larger polity – or not.

The Federalists argued that a larger federal polity would check the fits that from time to time sweep over small ones – and I agree with them. However a large federal structure will have some taxation. Equally, even a small group may tax a lot, giving greatly to some and taking greatly from others. The population of the later Roman Empire was very small by our standards, but the percentage of its area listed as “agri deserti’ tended to increase; I agree with those who suggest it was taxation that caused marginal land to go out of production. So I think I’d say it was the amount of taxation (relative to the community’s income) rather than the numbers of the citizenry that was a key variable, plus the degree of throughout-life separation between those who pay and those who benefit, above all where those who benefit include those with power.

bobby b (March 2, 2017 at 5:37 am), an actual war charity, rather than war loan, would indeed be a simple giving of the money by the payer. If said charity were also funded by the government, then a simple bookkeeping exercise could see both the war and the war charity as well funded as before. However I can quite see the state would not want to allow that liberty; where one is permitted to go, others would follow.

That said, I should mention in Miss Patch’s defence that Lloyd George had just become (arguably our worst) prime minister. Like Bill Clinton, Lloyd George screwed around a lot. Like Bill Clinton, he had his wife lie to protect him from political consequences. (Both Lloyd George and his wife lied in court under oath to escape political consequences that could have been fatal in those more prim and proper days – an “alienation of affection” case IIRC.) Unlike Bill Clinton, Lloyd George did not have nearly so much of a complacent press to assure women that he was their candidate – on the contrary, he had good reason to think the votes of the fair might be cast disproportionately against him. Thus he added a clear political motive to his personally vulgar manner of opposing women’s suffrage.

To us, looking back, it may seem obvious that by early 1917, Miss Patch’s cause was certain to win in the UK if the UK won the war, whereas the UK’s victory was a lot less certain at that particular date. But I can understand if she saw Lloyd George’s appointment as bad news. (Indeed, and not at all just as regards her cause, I could not agree more.)

BTW, I believe Lloyd George was key to destroying the UK’s Liberal party, letting Labour replace it as one of the two that counted. It is very had to replace, as against evolve, a major party in the English-speaking world’s two-party system. Lloyd George became so corruptly embedded in the Liberals that it was impossible to get him out, but after WWI his yet more and more evident corruption made him hard for ‘decent’ collaborators to tolerate – and hard for the electorate to believe in their election-time intra-party truces. They died of the tension.

It is true that the British Monarch and the Italian Monarch were less powerful than the German monarch – but PARTLY that was a matter of personality.

As for “true monarchies” – Snorri would seem to mean an absolute monarchy, for example no voting for War Credits in the German Parliament, just rule by decree.

Well there was a bit of that – for example Bismark increasing taxation in the early 1860s without the consent of the Prussian Parliament.

I think (at least hope) that Snorri will agree that an absolute monarchy, such as that of the Roman Empire, is to be avoided.

It is certainly anti Christian – as Christian theologians put the law of God (natural law) above the arbitrary commands of Kings.

Feudal monarchy was limited (“constitutional” monarchy) even as far back as 877 the King of France admitted that there were things he was not allowed to do – for example take land from one family and give it to another.

That is the basic difference between the limited (constitutional) monarchies of the West and Asiatic Despotism.

Supporters of unlimited monarchy are traitors to the West. And the German lands are part of the West.

But that does not mean a totally powerless monarchy is right either.

Little Liechtenstein gets the balance about right.

Neither an absolute monarchy nor a powerless one.

The monarchy as one element in the checks and balanced of a Balanced (or “Mixed”) Constitution.

Russian history is an interesting one.

The conventional approach is to describe Russia as a succession of one tyranny being followed by another tyranny, being followed by…..

But that leaves out many elements – the rights of the Cossacks, and the Free Peasants of the North, and the role trial of by jury before the First World War, and the operation of local government, and the national Duma (on and off) and so on.

Russia is very big and very complicated – any simple description of is history as just the history of tyranny is wrong.

It is a great historical “might have been” – what Russia would have developed into had it not been for premature war, and then Marxist Revolution.

Counter-Rant: Kim Jong-Un is Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Who in the world thinks this is any kind of example of any kind of “monarchy” except by sloppy thinking and playing merry hell with the definition? Communist regimes are neither republic nor monarchy and shouldn’t be lumped in with either for cheap points.

Just to be clear, I’m not taking Kim’s titles at face value. I’m taking them as tells as to what kind of government is in operation there – what kind of political formula, legitimizing principle, et cetera. forms the basis of the North Korean government. In a republic, the ruler justifies his rule by saying something like “Because I won the vote-counting game”. In a monarchy, “Because I own the country”. In a theocracy, “Because God will smite the country if not”. In a communism, “Because I represent the Workers”. In a junta, “Because I have the biggest army”. Of course few governments are purely one thing, but they do tend to cluster.

I joked a few threads back that if one really wanted to be contrarian, one could lump together communism and democracy (and nazism, for that matter) as demo-logic governments: those that justify themselves by appeals to some large chunk of demos. The Workers, The Voters, Das Volk, same kind of rot, right? Thereby conveniently labeling both the worst groups into the bin of “non-monarchy”.

The word “totalitarian” in that equivocation particularly grinds my gears for another reason. Totalitarian is not a form of government, nor even a modifier unique to dictatorship. You can perfectly well have a totalitarian monarchy, totalitarian democracy, totalitarian junta… or relatively libertarian forms of all of those. Surely it’s not that hard to imagine a military government that doesn’t give a damn how large, sugary or salty your soda is, the way various democracies have of late?

“Absolute monarchy”, meanwhile, has a useful technical meaning which is not synonymous with “totalitarian”: a monarch who is unrestrained by such things as a powerful noble class, or a Constitution, or the Church, or division of power, et cetera. He can treat the country strictly as personal property. Like the supposed droit de seigneur, it appears to be far less prevalent in history than in scaremongering about that horrible kingdom over there.

For all this fiendish advocacy, I’m not a monarchist. It’s more that I think the democratic transition was a bit of a red herring from the important things: level of technology and virtue of people. If you live five hundred years before the invention of antibiotics, life is gangrenous and then the plague gets you. If 90% of your countrymen have no respect for your personal property, odds are they’ll vote to take it in a democracy and the King will be one of the 90% in a monarchy. No allotment of suffrage can do much about either of these troubles.

FWIW, I agree with Erik’s “counter-rant”. I’m not a monarchist either (at least, not yet; I remain open to persuasion), but I can certainly see that it has features to recommend it. Just as democratic-style (“demos“) political systems have significant flaws. The issue is not as clear-cut as Julie would have us believe.

“Democracy is a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance.” – H. L. Mencken. Indeed.

The problem with monarchy, whether constitutional or absolute is that for every good monarch there is at least one bad one, usually more…

Niall, I had the feeling when typing my previous comment that the connection between paras 1 and 2 might go unnoticed 🙂 I was trying to reply to a specific point made earlier in this thread (forget by whom) – in fact, not only is it a point often made, it is almost a received truth that we vote on how our tax money is spent.

Of course the size of the constituency is not the only factor that affects the legitimacy of taxation – but that said, the other two factors you mention seem to be well-understood and accepted by most, so I didn’t even think it needed to be mentioned.

JG sums it up well.

And I never said nor implied nor thought that “democatic-style political systems” are or ever can be flawless.

.

“Totalitarian” means that every aspect of life is under the control of somebody other than the individual whose life it is. You’ll notice I said “totalitarian dictatorship.” Understanding “dictatorship” in the conventional way, “totalitarian” modifies “dictatorship,” and it serves among other things to point out that the two are not necessarily the same. (Not all dictatorships are totalitarian, nor are all totalitarian regimes dictatorships in the sense that the law is only and entirely what the dictating entity says it is.)

Not all military juntas give rise to dictatorships, or at least to totalitarianism.

.

Laird: “Julie would have us believe” is downright insulting. I retain the right to state my opinion (as long as it doesn’t cause dyspepsia in our hosting hippo), even in rather emphatic terms; but to state an opinion is not an attempt to force it down anybody’s throat.

I made a point which I think is a good one. Others may disagree. In this case, the fact is that I had thought we are supposed to be libertarians in that we believe that each person’s self-determination is not to be breached past the absolute minimum. The question is, what sort of political system is likely to operate per this principle most closely and for the longest time? (Nothing is forever. With the two notable exceptions.)

I see nothing in the history of “absolute” anythings that looks like a very good bet. You can look at this or that system, and find plenty of places where it has failed in honoring self-determination, or in attempts to protect the citizenry physically. And in the worst of systems, or rulers, you can usually find something, however negligible, that all by itself could be considered pretty good. If our American democracy is on the short-list of dreadful systems, as seems to be a popular opinion among “libertarians” these days, at least we have not had violent rebellions every four or eight years. And even Hitler gave his Jewish doctor a pass, if memory serves. They say that at least Mussolini made the trains run on time. (Although I’ve heard that’s not true.)

And our Maximum Leader is not a dictator by any means, not even the Sith, however much this may have caused him to weep, or to rant vociferously, if vacuously, from time to time. Nor does our electorate impose totalitarian rule, although I would still like to haul the raccoons over next door and let them tear up her roof. It might give her a whole different slant on things. Our particular demos is not totalitarian; partly because our people do have somewhat of a live-and-let-live attitude still, and partly because it includes so many factions pulling this way and that, so that none of them really has complete power.

. . .

Also, there is overlap between the categories “Democracy” and “Monarchy.” It’s possible to have a monarch who is elected for life, or for some set term. Then we can deal with the issue of keeping him or her within reasonable bounds; such as instituting a Constitution by which everyone, including said elected monarch, feels bound — whether anyone likes it entirely or not.

Off-topic: can anybody here remember which Act of Parliament it was that only passed because the man counting the “ayes” inflated the count? I think it was some important human rights legislation but I might be wrong. The only other details I remember was that it was back in ye olden days and the count somehow involved counting the members as they returned to the chamber, but the fella counting the “nos” wasn’t paying attention to his counterpart, who noticed, and realised he could pull a fast one.

Any help would be appreciated.

MM: I think you’re speaking of The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679.

(Fat guy was jokingly counted as ten votes as he walked back in the door, counter noticed his auditor wasn’t paying attention, and left it that way.)

Bobby B: legend

Laird,

How is it possible to believe in freedom, but believe that one person should have the power to remove freedom from others at a whim?

And the problem with any form of dictatorship (here including supreme monarchy) is not necessarily the dictator (we might devise a system to select only ideal dictators (although that would be a crap system in my book – the ideal dictator would immediately step down and hand power to the individuals who they were appointed to rule, which might be ideal but is not the system that was designed)). It is with the centralisation of power, which creates a court and courtiers, as the ambitious and the venal will need proximity to the one with power to access that power themselves. The courtiers might be those concerned with ‘equality’ and identity politics rather than aristocrats, but such courtiers natually flock to anybody with power over others. And they tend to be given functions, because no one person with supreme power can do anything – so we get appointees with power. And these appointees’ power derives from the monarch or dictator, who cannot therefore let it be challenged without their own position being challenged. And the need to defend this power destroys the rule of law, as the law becomes discarded in favour of whim or expediency (the law may be changed, but law being changed for a particular case, as happens in this sort of situation, indicates the rule of law has broken down and that law is now the tool of the government against the people).

What supreme rulers (yes, I know I like to keep switching terminology – it makes for a better read hopefully) inevitably produce therefore, even before a potential weak successor, is systems prone to corruption and inefficiency, where proximity to power becomes the road to power, which excludes merits and reduces freedom. Historically this is obvious – the republics (including the constitutional monarchies) are the countries where wealth has increased for all, whilst the states with supreme rulers are those where, mineral wealth occasionally excepted, there is the least development and the greatest continuation of poverty. Note that China and Vietnam, where wealth has increased, have taken on many republican characteristics, most notably no single supreme leader in the Mao Tse Tung or Ho Chi Minh mould. The failure of Venezula or North Korea could equally be ascribed to the power (not necessarily constitutional legitimacy – power is about ability to act) that is focussed on a single leader. The underlying weakness of Russia is also ascribable to the same phenomenon.

So, unless you actually believe that economic freedom is not the basis of personal freedom (if so, I’ve got some peasants (edit: not mine personally – apparently serfdom is illegal in England) who might have something to tell you…), then it seems a bit difficult to justify supporting any sort of supreme ruler. That said, I much prefer constitutional monarchs to elected presidents, for pretty much the same reasons. But power itself has to be as decentralised as possible to offer the best chance of freedom, and you don’t decentralise power by putting it all in one pair of hands.

Bobby b,

So a fundamental of the UK’s freedoms (and an underpinning act in the US’s, Canada’s, Australia’s, New Zealand’s, Singapore’s etc) was apparently passed because someone was making a fat joke?

That makes me feel a whole lot better about the world. And perhaps means we should be wary of the fact that Nicholas Soames has apparently lost weight.

Watchman,

Indeed. And just imagine what the world would be like if Lord Grey had been a more principled man.

Freedom thru chicanery!

If the arc of the universe bends towards justice, it’s only because somebody grabbed hold of it with a pair of pliers and pulled.

I’m baffled by a discussion of which system is better with no definition of “better.”

If “trains running on time” is the criterion, I could understand some of the choices defended here, but if there’s any component of “recognizes and empowers free individuals”, the choice narrows.

The historical erudition in this thread is quite impressive. I reply to Paul Marks because he brings up issues close to my heart; and apparently we entirely agree, which has not happened for a while.

This is a matter of definition, of course. My understanding is that “absolute monarchy” is used to refer to European Renaissance (ie post-feudal) monarchies. Those were not really absolute, because the Monarch (normally) could not raise tax revenue without approval from taxpayer representatives. However, they were still the form of government closest to arbitrary rule, except for “oriental despotism” and (even worse) xx/xxi century totalitarian regimes.

I did say “normally”.

That goes without saying.

I am fond of the neo-republican definition of freedom/liberty: you are only really free if nobody has power over you. You are only partially and temporarily free if someone has power over you, but does not use it.

This is an important reminder. Things got worse during the Renaissance, however; except in the Republic of Venice, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. (Maybe a few other places.) It took a bit longer in England/Britain.

Right on!!!

Both “monarchy” and “democracy” are, or ought to be, checks on the power of the ruling class/oligarchy. NOT the ONLY checks, mind you: it is ALSO necessary to foster divisions within the ruling class. (As long as they do not lead to civil war of course.)

That is why i do not pay much attention to rants and counter-rants, on this blog and elsewhere, about the relative virtues of monarchy and democracy **as systems of government**: as such, monarchy is dead (except for Saudi Arabia, North Korea, and maybe a few other places), and democracy is a pipe dream.

Watchman:

Let me ask you and Laird and others who have similar opinions, what specifically those reasons are? I can only think of one possible reason, which is that such a monarch might eventually gain experience which might make him a better ruler than one whose term of office is relatively short. But that, again, would depend on the specific monarch and also on his term of office — and the terms of his office, of course; and most importantly, perhaps, the degree to which he feels bound by the constitution.

The only other thing I can think of that sounds half-way plausible is the argument for hereditary monarchy, which depends on the idea that the kiddies are reared to the art of good governance. To this, as I said above, Bah humbug!. It can and has happened in individual cases, I daresay, but it’s a mighty weak reed to support the contention that such is the likelihood.

So, I am honestly interested in the brief for a constitutional monarchy as opposed to an (American-style) presidency.

Julie: i don’t MUCH prefer constitutional monarchs to elected presidents, but i can easily think of a few more reasons to have a constitutional monarchy rather than an elected presidency.

Item #1: a hereditary monarch knows that (s)he is only tolerated as long as (s)he [i’ll use she from now on] is not blatantly going against the will of the people. An elected president, by virtue of being elected, can always claim to embody the will of the people, even when going against it.

Item #2: a hereditary monarch thinks about the long term: as long as she behaves, she’ll be monarch for life, and her heir will succeed her; if she screws up, like the Bourbons, Hohenzollerns, Romanovs, and Savoia, then it’s game over.

Item #3: an elected president only represents the half of the country that voted for her; a monarch represents all the people who are willing to tolerate her.

The 3 items above are closely related, and maybe they are really just one item, but i’d have to think about it.

————

A couple more items, one about presidential systems such as the US, the other about parliamentary systems.

The US system: In a constitutional monarchy, the monarch is a check on the executive; in the US, the president is also head of the executive and therefore cannot act as a check.

Monarch-deprived parliamentary systems: the president is elected by parliament independently of the head of the executive and therefore can act as a check on the executive; but both are elected by the majority in parliament, and therefore the president cannot be much of a check.

I must stress that i do not regard any of the above arguments as conclusive.

Bobby b,

Sorry – I was thinking of individual freedom as the ideal but did not communicate it. Although my explicit reference to better systems was not to that but to a hypothetical ideal dictatorship…

Julie,

Presidents seek power. Constitutional monarchs accept it with limits accepted. Might not be always the case, but close enough for me to distrust Presidents.

Snorri, thank you for taking the time to answer. I do have some problems:

1. A hereditary monarch is just as likely as some other ruler to think that if necessary, guns will keep the natives quiet. If so, he may know that his hold on power will be stronger if he can use propaganda and presents to keep them from getting restless, but as long as he thinks he’s got the guns, he thinks he’s got the upper hand. After all, in the end “Government is force,” or some such slogan.

.

2. A hereditary monarch is just as prone to human fallibility as anybody else, and one of the unfortunate traits of our nature is to think that what is will always be. Yes, eff-uppery past some point of people’s endurance will end in tears for the Prince, but especially when one is long-ensconced in a protected position, let alone a protected position of authority, there’s a tendency even for the prince to think that he can slide by with only minimal exhibitions of interest in “the will of the people.” (Of course, there is no such thing, but that’s another discussion for another time.)

And as I noted already, monarchs do not necessarily die of natural causes; and as for worrying that one’s son or daughter or other protegé might not accede to the throne if one screws up, not all royal guardians have exhibited overwhelming concern in that area. (Besides that, children are cussed creatures. The “best” upbringing in the world, whatever that is, doesn’t guarantee the child will become what Mom or Dad wanted. He may fall in with bad company anyway, one of whom thinks he sees the main chance and forcibly removes our Princeling as an obstacle.)

So it can very well happen that a monarch knows the importance of not screwing up, both to himself and his own rulership, and to his natural or designated heir — again, in both regards. But depressingly many rulers have done so anyway.

Also, sometimes people get just plain tired of being Mr. or Mrs. Big. Even the mantle of power may grow heavy on the shoulders.

.

3. An elected president may or may not represent “half the people” in any meaningful sense: Usually, fewer than half of the electorate bother to vote at all. But that’s secondary. In a technical sense (i.e. according to one’s definition), a monarch (of any type) or a president may “represent” at least the people who voted for him; but in reality said representation tends to have lots of holes in it.

I really don’t see whether it matters whether one is elected to leadership or inherits the position. Either way, what does people’s toleration of the ruler or the president have to do with whether he or she “represents” them? (And, “represents” in what sense? As a matter of appearances to the outside world, as when a basketball team represents its school at the Conference games or a diplomat “represents” his country when he deals with his foreign counterparts? Or as a matter of trying to get for all of his people, or at least the ones most in his favor, what they want — or what he thinks they should have whether they want it or most definitely do not?)

For instance, I did “tolerate” the Sith in the sense that I didn’t off him or otherwise attempt to depose him, but in no way did I think that he “represented” my interests; and it’s a stretch to say he represented the American people, or at least me, even in the technical sense of appearing as “the face of America” at the diplomatic level, since in fact what he did was to misrepresent us at every opportunity, whether here or abroad.

.

So, it seems to me that the points you bring up are awfully “iffy” in the real world. Sometimes the system might work out well, or at least tolerably; but I think it depends a great deal on the character of Mr. or Mrs. Big, among other things.

. . .

Another question: In the final paragraphs, you begin by saying

“In a constitutional monarchy, the monarch is a check on the executive…”

What do you mean by “the executive”? In Britain, for instance, would you mean the Prime Minister? And in any case, even in a constitutional monarchy I don’t see why the monarch would be debarred from having Executive powers. Indeed, shouldn’t the constitution state who is to be vested with executive power? (As well as specifying just exactly what the Executive is empowered to do?)

Watchman,

Some presidents seek power; some, I think, probably more have it thrust upon them — as do some monarchs, whether or not “constitutional.”

Either way, the problem is the same for both: Why should the monarch or the president obey the constitution? Possibilities:

1. His own conscience compels him.

2. He has a relaxed, go-with-the-flow nature that, in some circumstances, might make it just plain easier to follow the thing. *Yawn*

3. He does like power and being Mr. Big, so if following the constitution seems likely to help him retain them, follow it … unless, of course, it becomes really really inconvenient. Oh, and he might do it for the kiddies — his own, that is.

4. Because some among the people are working on stringing him up, and it seems prudent to try to mollify them.

Those are what I come up with.

Well, I keep advocating time-share governments. We would all have a chance to rule! If a person wanted to be a citizen, then one would need to perform some community service (militia, volunteer fireman, rescue services, street patrols, etc.) for 11 months of the year, and then have the right to be a member of the local county for one month a year, voting on laws, making appointments to conferences with other counties, etc. If one needed a permanent public service, one could have contests amongst the services, and select the champions to be the public servants on a permanent basis, subject to performance standards. If you didn’t want to be a citizen, you could use the public roads, but would have no say on the rules of the roads. Seniority of citizenship would determine speaking order. This would be my version of a libertarian society.

What voting does is allow the majority to get rid of a government without killing people.

It is certainly not perfect – but, as Winston Churchill pointed, not allowing the majority to get rid of a government they detest is worse.

Julie near Chicago (March 2, 2017), and later posts that reply to hers, discuss what virtues a constitutional monarch might have, but do not mention any of the main points IMNSHO.

That a constitutional monarch is outside the world of routine politics is valuable in perception, in day-to-day situations and in extreme ones

– In perception: in a republic (modern-sense), there is no alternative to the president as the human representative of the country, but the president is also the head of a party, so typically hated by all who voted for the other guy while making themselves believe disaster certain were the majority to disagree. In the UK, we sing ‘God save the Queen’, not ‘Hail to the chief’. The Queen lives in a palace, the PM in number 10 Downing Street. It all helps keep Britain and Britain’s government a bit more obviously separate.

– In day-to-day: a monarch, like any of us, can live in a bubble, but she does not live in the politicians’ bubble. Every week, the PM is forced to discuss things with someone from outside a politician’s usual set; someone who has a right to have her questions answered, to be told anything and everything, and a right to order the PM to listen attentively to any advice and warnings she chooses to give.

– In extremis: in the late 1800s, Japan and China handled the existential threat of the west very differently.

— In China, the emperor was very much simply the head of the system. Thus the system’s response to the arrival of the west (e.g. buying and dismantling railroads in hope of restricting western-caused difficulties to the coastal ports) had no alternative but revolution, with all its disastrous effects.

— In Japan, for a thousand years, the monarch functioned very much as in the UK. A battle rather than an election decided who would be recommended to the emperor as the new Shogun, but otherwise it was very similar. When the west arrived, the emperor could therefore see it differently to the system, The emperor was outside the sphere to which a web of vested interests and group-think confined Japan’s actual rulers, yet had the formal prestige to confer ancient legitimacy on a radically-modern west-handling approach. Thus the emperor offered a third way between the different-ways-to-fail paths of vested-interest rejection and vicious revolutionary acceptance.

Thus in the UK, I see the monarch as having obvious everyday value plus being an insurance policy. The cases in which the policy will ever pay out are rare and the payout uncertain, but it costs us less than nothing to keep on renewing the policy, since the monarchy pays for itself in tourism (and probably again in advertising), the curator functions of the monarchy would have to be done anyway, and the whole thing (financially – i.e. the civil list, as it is called) was fairly bought and paid for in exchange for the foreshore (which the monarchy owned).

Julie: my arguments for constitutional monarchy are indeed iffy, and indeed the only constitutional monarchy that i hold as a model is the UK, and then only between 1688 and the early xx century.

Having said that, my iffy arguments at least are pertinent to your question. By contrast, your counter-arguments are not pertinent, because you shift your ground from constitutional monarchy to “hereditary monarchy”.

Actually, your counter-argument #3 is relevant. The fact is that i did not express myself clearly: the problem with an elected head of State is not that little more than half of the people voted for her, it’s that almost half of the people voted against her. Nobody voted against Queen Elizabeth II.

As for this:

If you don’t see it, then you should ask yourself what counts as a constitutional monarchy, before asking what its advantages are.

BTW if you think i am more snarky than usual, wait till you see what i am going to say to Paul Marks tomorrow!

Snorri, I got to admit you gots me in re the shift from “constitutional” to “hereditary.” It was entirely inadvertent — I was really more exercised about the latter than the former, as the original rant I think at least hints.

… It’s amazing, the things you can find to fret about between the time when you turn out the light and the time when sweet sleep knits up the ravelled sleeve of care [with luck and if the Great Frog is in a generous mood] ….

.

However, what puzzles me is what you mean by “the Executive” (politically, that is) in general. As I questioned above.

.

By the way, if you’re taking the American President as your representative example of a President, you might want to check — I don’t believe we’ve had any female Presidents lately. ???

Niall, I am pondering your comment, which, as far too often *g*, presents information of which I was unaware. Thanks. :>)

Niall Kilmartin @ March 3, 2017 at 12:39 pm:

I don’t think this accurately states the situation in either country.

In China: none of the Emperors after Daoguang (d. 1850) had any real authority. After 1861, the Dowager Empress Ci Xi had near-total control, as effective leader of the dominant court faction. Ci Xi was a reactionary, as were most of her faction; forced by circumstances to allow modernization, they often tried to roll it back or exploit it.

In Japan: the Emperor Meiji (reigned 1868-1912) was a teen-aged boy at his accession, the figurehead of the dominant political faction. The men of this faction were able modernizers, who carried through Japan’s transition.

Thus the difference was not the relative positions of the two Emperors, which were about the same. Rather it was in the quality of the factions which controlled the Emperors and thus the governments.

Niall:

I am curios, is there any evidence of this actually occurring, present or recent-enough past? And is there any real external incentive for the monarch to ask such questions and to offer such advice or warnings? I am asking about the day-to-day context, as I can see how in extreme situations the monarch would be motivated solely by the acute sense of urgency, similarly to the rest of the population.

Rich Rostrom (March 5, 2017 at 4:27 am), in my contrasting of Japan and China in the 19th century above (March 3, 2017 at 12:39 pm), I was using ’emperor’ as a synonym for the institution. In the late Victorian period, the old Empress was the de-facto wielder of the institution’s power in China. In japan, the movement that would achieve what is called the Mejii restoration began under Emperor Kōmei (Emperor Meiji’s father) and completed under his teenage successor.

My point is illustrated by what was said to those pushing ‘choice’ at the Department of Education:

(No doubt some across the pond are thinking the same of Betsy DeVos.) The shogunate administration expelled such mutant organisms too, but separation of ruling from reigning created another space for them in Japan.

Alisa (March 5, 2017 at 11:19 am): “I am curious, is there any evidence of this actually occurring …”

If you mean, is there any evidence of this weekly meeting occurring, yes. I think it was Harold Wilson – Labour leader and PM from time to time in the late 60s and mid-70s) who once said that it was the only meeting in his week that didn’t leak. (He was one of those PMs who felt – not without cause – that some of his bitterest enemies were inside his own cabinet. 🙂 ) The remark has been repeated by several of his successors. Some have also said that the regular chance to discuss things with someone outside the routine political realm is something of a relief.

What advice her majesty gives is usually not known. IIRC, when a group at a garden party asked her majesty to tell Tony Blair that he did not understand rural people, she replied that she had already told him this more than once (and implied she would raise it again). Tony, after ceasing to be PM, was publicly very positive about the general benefit he had had from these talks with her majesty, but did not mention this specifically.

There is also the regular meeting at which her majesty approves laws. All attending ministers have to stand throughout, while IIRC chosen ministers present laws appropriate to their department, to which her majesty assents. (It is – sadly in some ways – 300 years since another queen – Queen Anne – last replied ‘La Reine s’avisera”, which IIRC is Norman French for “The Queen will think about it”, which is a polite royal way of saying ‘no’.) The royal assent is the last stage of adding a new law to the (too!) many that we have.

Alisa (continuing March 5, 2017 at 4:45 pm above): “… ‘La Reine s’avisera’, which IIRC is Norman French for ‘The Queen will think about it’ …”

Literally, “The Queen will advise herself”, i.e. as against taking the advice of her PM and ministers.

Obviously, the “weekly meeting” is in fact affected by the vagaries of schedules, e.g. when a PM returns from a foreign summit, a meeting with the Queen is arranged where he gives her a report on it, and that kind of thing.

Niall, I did know about the weekly meetings before, I was just wondering how effective they have been, generally speaking. Your reply did give me a fuller picture, so thank you for that.

Alisa: the weekly meetings between the Queen and Thatcher are said to have been quite effective in making Thatcher feel the need for a stiff drink.

😛

Alisa, the sole example I quote suggests the Queen felt Tony Blair was not paying as much attention as he could to her advice about country folk during the latter part of Tony’s time as PM. It has been suggested that some of Labour’s spiteful anti-rural antics were Blair’s payment to the left for not unseating him over the Iraq war – which could be read as meaning that her majesty’s advice was not ineffectual until it became an internal Labour political necessity. However except for the coincidence of timing, and common sense, I know no evidence beyond rumour for any of that.

Niall, this seems to be one of those cases where rumors, while unreliable as evidence of actual facts, can give one a sense of the real general dynamic of events.