We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The problem I often see in left-libertarian writing is the sense that the world of freed markets would look dramatically different from what we have. For example, would large corporations like Walmart exist in a freed market? Left-libertarians are quick to argue no, pointing to the various ways in which the state explicitly and implicitly subsidizes them (e.g., eminent domain, tax breaks, an interstate highway system, and others). They are correct in pointing to those subsidies, and I certainly agree with them that the state should not be favoring particular firms or types of firms. However, to use that as evidence that the overall size of firms in a freed market would be smaller seems to be quite a leap. There are still substantial economies of scale in play here and even if firms had to bear the full costs of, say, finding a new location or transporting goods, I am skeptical that it would significantly dent those advantages. It often feels that desire to make common cause with leftist criticisms of large corporations, leads left-libertarians to say “oh yes, freed markets are the path to eliminating those guys.” Again, I am not so sure. The gains from operating at that scale, especially with consumer basics, are quite real, as are the benefits to consumers.

– Steve Horwitz.

(Hat/Tip, Econlog, which has other thoughts here.)

I am all in favour of ending “corporate welfare” – for ALL sizes of firms; I think tariffs, subsidies, “soft loans”, eminent domain property land-grabs, huge extensions to intellectual property such as patents (I think some forms of IP are okay, the more clearly and narrowly defined), and so on, count as such welfare. But none of this means we have to make the error of automatically saying that small firms are somehow less bad than larger ones are. And remember that when a firm, even a brilliantly-run one with no government aid, gets large, that unless it is very lucky, its sheer size can reduce its nimbleness in responding to new challenges to its position. I don’t have the data to hand, but I read somewhere that of the firms in the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1950, fewer than half are still there.

So the next time you hear someone waxing indignant about WalMart or Tesco’s, bear that sort of thing in mind.

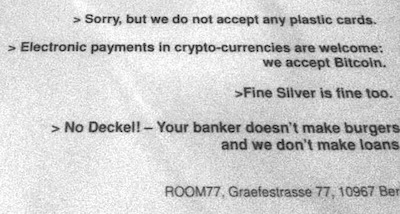

I would recommend clicking on the picture for the large version, in order to read the house policy of the establishment for the use of firearms on the premises.

My apologies for the poor quality of the picture. The light was dim, and I merely had a phone camera. I could have stolen the menu in order to get a better picture, I suppose, but I would not dream of violating the property rights of people of such obvious soundness.

The world’s creative activities can be placed along a line. At the good end of this line are the activities that politicians don’t care about, or even better, don’t even know about. The most important quality possessed by such activities is that politicians – by extension, most people – don’t consider them to be important, necessary, vital for the future of our children, etc., so they leave them alone. These things tend to be done well. And at the opposite end of the line, there are the things that politicians and most people do care about, like schools, hospitals, transport, banking, power supplies, broadcasting, and so forth. These things are done anywhere between rather and extremely badly. It is not that they are not now done at all by businessmen. But this is not enough to ensure excellence of output. If the politicians stand ready to be the buyers or lenders of last resort, to “ensure” that this or that is “always” done properly, that it (some scandal or catastrophe that would destroy a proper business) will “never happen again”, then relentless disappointment will ensue. Bad enterprises, instead of just being left to die, are endlessly and expensively fretted over, or worse, coerced into mad purposes that only politicians could dream of caring about, like trying to change (in politics speak: “fight”) the climate. Bad schools or hospitals or banks or power stations or TV channels, rather than just being closed or cannibalised by better ones, are inspected, given new targets and new public purposes, subjected to ever more regulations, asked about repeatedly in places like the House of Commons, and above all, of course, given more and more, and more, money.

It would be tempting for a visitor from the planet Zog to suppose, then, that only trivialities will be done well by twenty first century humans. Luckily, however, both people and politicians have bad taste, and bad predictive powers. As a result, many things are considered to be trivial which are actually not, and they get done and done well. Also, things which are thought to be trivial but which later turn out to be hugely important, but because the politicians and most people at first reckoned them trivial, also get done well, or get done well until such time as the politicians start taking an interest. Alas, things at first considered trivial but later deemed important tend from then on to get done badly, but at least they got done in the first place.

A good example of something which, as of now, is still considered so insignificant as to be beneath the attention of politicians is the computer keyboard.

Computer keyboards have got steadily better and better throughout the last three decades, yet at no point in the story did politicians do any “ensuring” or “supporting” of computer keyboards or of the enterprises that designed and built and sold them, even as more and more politicians became familiar with using such things. No “framework” more complicated than criminal and patent law was imposed upon the enterprise of making computer keyboards. No government minister has particular responsibility for computer keyboards. Computer keyboards thus continue to be made very well, and better with each passing year.

Yet who would now dare to say that computer keyboards are not important? Everyone who ever has anything to do with Samizdata has at least this in common, that they use a keyboard at least some of the time, and in lots of cases, surely for something like half of life when awake. For many a modern working citizen in the year 2012, the big difference – well, a (can you register the italicising of that one letter? – you can now) big difference – between misery and happiness, to update Dickens – the difference between repetitive stress syndrome and constant cursing on the one hand, and daily digital (in the literal bodily sense) bliss on the other hand (talk of metaphorical hands is all wrong in this connection but you surely get my point) – is a nice computer keyboard. → Continue reading: My new computer keyboard

Blaming the prince of the fools should not blind anyone to the vast confederacy of fools that made him their prince.

– via Bernard Goldberg

Even if you haven’t any time for Conrad Black, recently released from a US jail after being convicted of corporate wrongdoings (there is something about the conviction that makes me smell a rat), this review, by Paul Johnson, of Black’s recent book contains a rousing assault on the darker side of the US legal system. Excerpt:

America’s criminal courts now insist on convictions at the expense of any other consideration, above all of justice. They are more like a court martial than a civilian establishment of law. The presumption of innocence has been abandoned. I recall, during my military service, a senior provost martial telling me: ‘If a soldier is court-martialled one must assume he is guilty, otherwise he would not have been charged in the first place.’ That is contrary to all the principles of English justice but it now approximates to the approach of the American prosecuting authorities. The assumption of guilt is sanctified in law by the grotesquely unjust plea-bargaining process, which saves the accused from total financial ruin by forcing him to plead guilty to some of the crimes with which he is charged, however innocent he or she may be. Plea-bargaining in turn leads to a multiplicity of indictments by prosecutors, which adds a judicial to the financial compulsion of the innocent to bargain.

Hence the American prosecution practices are what the law calls ‘a derogation from honest service’. The US prosecution service, in heedless pursuit of convictions, does what it wants and prosecutes whoever it wishes for as long as it likes. Thus, over 90 per cent of prosecutions are successful, a higher proportion than in either Putin’s Russia or Communist China.

In my view, the plea-bargaining system is, as Johnson notes, one of the reasons why even the most Atlanticist Brit is concerned about the way in which the US-UK extradition arrangement tends to work unfairly against Brits who can be sent to the US without a, their case having to be shown to be worthwhile before a UK court and b, face the disgrace of the plea-bargaining system, which ends up with people settling for a criminal record rather than take their chances with a hideously expensive defence. By the way, here is a Canadian take on plea-bargaining. The Volokh Conspiracy had thoughts on this a while ago.

Like and admire much of the US as I do, its legal system, and incarceration rate, is nothing to admire.

By the way, it is good to see Johnson returning to some of his old fire in articles such as this. In his older years I suppose he has slowed down a bit. As a reminder of him at his best, I can recommend his Birth of The Modern.

James Rummel of Chicagoboyz posted this sad but telling photo essay about what happened when a hobo moved into a shed next to a restaurant that had closed down.

Strictly speaking, I wouldn’t call this a tragedy of the commons, more a tragedy of the consequence of poorly enforced property rights. The events James Rummel describes could just as easily happen here; the recent changes in the law that made squatting in residential properties a criminal offence do not apply to commercial buildings. Of course squatters can be evicted by civil proceedings as before, but it is not an easy process.

I would guess that the sympathies of most Samizdata readers will be with the property owner – and so they should be. To be stuck with a deteriorating building that is costing you money every day that goes by is no joke. Quite soon, I would guess, a point of no return is passed beyond which it becomes uneconomical to even try to make the building attractive to a potential buyer or tenant, particularly if, as in this case, someone is actively subverting any attempt to do that. To rub salt in the wound, you can bet that all your nice well-meaning neighbours are tut-tutting at what a heartless slum landlord you are, leaving that fine building to decay. Large numbers of people apparently do believe that landlords let buildings decay for the fun of it. Here are some of them, in the comments to another Guardian article by the same Ally Fogg whose article about the man arrested for burning a poppy I was praising the other day.

However sympathy need not be a zero sum game. Sympathy for the landlord should not preclude sympathy for the homeless man. Many factors can make a man or woman homeless; drink, drugs, unemployment and shattered relationships among them. It is also possible, or even probable, that the hobo’s plight, as much as the landlord’s, was ultimately caused by official contempt for property rights. Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson” is more than half a century old now, but the lesson still hasn’t been learned.

It may reach a point where many landlords not only cease to make any profit but are faced with mounting and compulsory losses. They may find that they cannot even give their property away. They may actually abandon their property and disappear, so they cannot be held liable for taxes. When owners cease supplying heat and other basic services, the tenants are compelled to abandon their apartments. Wider and wider neighborhoods are reduced to slums. In recent years, in New York City, it has become a common sight to see whole blocks of abandoned apartments, with windows broken, or boarded up to prevent further havoc by vandals. Arson becomes more frequent, and the owners are suspected.

That passage was describing the effect of rent controls. Other restrictions on the property rights of landlords, such as ever-stricter demands as to maintenance and compulsory inspections, making it extremely difficult to evict a non-paying tenant, or forbidding tenancies with short notice periods even by mutual agreement, work a little more slowly but get to the same sorry result in the end. When the government penalises landlords it also penalises tenants and those who would like to be tenants but cannot find a place to rent.

I have made no secret here of my admiration for Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature.

I was especially struck by the pages where he describes The Enlightenment, and I have taken the liberty of scanning these pages into my personal blog. If anyone connected with the book objects, my posting will be removed, so if a brief exposition of what The Enlightenment was and how the ideas behind it all fitted together appeals, go there, soon, and read on.

Two questions naturally arise from Pinker’s summary. First, is it an accurate description? Or does Pinker impose a coherence upon Enlightenment thinking that it never quite possessed for real? (My guesses: yes, and no.) Second, if I am right that Pinker does describe the unified scientific and moral agenda of The Enlightenment accurately, then how true are these ideas? Were errors made, as well as truths declared? Did these errors do harm? (Did any of the truths do harm?)

I could go on, but prefer not to. Suffice it to say here that it’s there if you want it, for the time being anyway.

Keynesian policies will keep us in a constant loop of distorted markets and growing imbalances. They guarantee us a Groundhog Day of economic depression.

— Detlev Schlichter, 8th November 2012

…triple-dip recession…

— The Bank of England, 14th November 2012

I did not write what follows. It was sent to me by my regular correspondent, Niall Kilmartin. – NS

When I first started reading Edmund Burke, it was for the political wisdom his writings contained. Only many years later did I start to benefit from noticing that the Burke we know – the man proved a prophet by events and with an impressive legacy – differed from the Burke that the man himself knew: the man who was a lifelong target of slander; the one who, on each major issue of his life, gained only rare and partial victories after years or decades of seeing events tragically unfold as he had vainly foretold. Looking back, we see the man revered by both parties as the model of a statesman and thinker in the following century, the hero of Sir Winston Churchill in the century after. But Burke lived his life looking forwards:

– On America, an initial victory (repeal of the Stamp Act) was followed by over 15 years in the political wilderness and then by the second-best of US independence. (Burke was the very first member of parliament to say that Britain must recognise US independence, but his preferred solution when the crisis first arose in the mid-1760s was to preserve – by rarely using – a prerogative power of the British parliament that could one day be useful for such things as opposing slavery.)

– He vastly improved the lot of the inhabitants of India, but in Britain the first result of trying was massive electoral defeat, and his chosen means after that – the impeachment of Warren Hastings – took him 14 years of exhausting effort and ended in acquittal. Indians were much better off, but back in England the acquittal felt like failure.

– Three decades of seeking to improve the lot of Irish Catholics, latterly with successes, ended in the sudden disaster of Earl Fitzwilliam’s recall and the approach of the 1798 rebellion which he foresaw would fail (and had to hope would fail).

– The French revolutionaries’ conquest of England never looked so likely as at the time of his death in 1797. It was the equivalent of dying in September 1940 or November 1941.

It’s not surprising that late in his life he commented that the ill success of his efforts might seem to justify changing his opinions. But he added that “Until I gain other lights than those I have”, he would have to go on being true to his understanding.

Of course, the background to these thoughts is reflecting on the US election result. Reflecting on how much worse it was for Burke is consoling. Choosing to be truthful in politics often means choosing to be justified by long-term events not short-term elections.

Two weeks before, I’d have guessed a Romney victory with some confidence, but the night before the election, I realised – rather to my surprise – that I expected Obama to win. I took myself to task over these negative thoughts, but it made no difference: I still expected Obama to win. On Wednesday morning, I was glad that being British gave me some feeling of insulation from it (not that our own government has been anything to shout about for a long time – shout at, maybe), although I fear the ill consequences will not all be confined to the far side of the pond.

Burke was several times defeated politically – sometimes as a direct result of being honest – and later (usually much later) resurged simply because his opponents, through refusing to believe his warnings, walked into water over their heads and drowned, doing a lot of irreversible damage in the process. Even when this happened, he was not quickly respected. By the time it became really hard to avoid noticing that the French revolution was as unpleasant as Burke had predicted, all the enlightened people knew he was a longstanding prejudiced enemy of it, so “he loses credit for his foresight because he acted on it”, as Harvey Mansfield put it. Similarly, when ugly effects of Obama’s second term become impossible to ignore, people like you and me will get no credit from those to whom their occurrence is unexpected because we were against him “anyway”.

Even eight years is a shorter time than any of Burke’s epochs. If the euro dies in less than another four years, maybe we should think ourselves very lucky. In our health service, the ratio of administrators to doctors and nurses passed 100% much longer ago than four years or even eight, and the NHS is still a sacred cow. Perhaps US citizens should think themselves lucky that adverse effects of ObamaCare may show soon and be noticed.

Since Burke was admired by Churchill, here’s a Churchill quote: “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.”

And a related Burke one: “The conduct of a losing party never appears right: at least, it never can possess the only infallible criterion of wisdom to vulgar judgments – success.”

“Nobody pretends that hiking these taxes means “ordinary people” will have less tax to pay. But most folk still believe that companies can be made to pay taxes, shifting the burden away from the rest of us. I have news for you: they can’t. Corporations are artificial legal constructs: only people can ever pay taxes. The burden of taxes supposedly levied on companies is borne either by investors (through reduced returns on their capital), workers (via lower wages) or consumers (as a result of higher prices). Targeting firms is just a way of stealthily taxing these people, ensuring nobody really understands who is picking up the bill. It is because we’ve forgotten about these basic principles that we’ve ended up with a dysfunctional and incomprehensible tax system, as exemplified by the row over the practices of Starbucks, Amazon, Google and others.”

Allister Heath. (Non-UK residents who don’t subscribe may not be able to see the full Telegraph article, but it seems that quite a lot can, so I am putting this up with a disclaimer.)

Blogger Tony Newbery of Harmless Sky tried to use the Freedom of Information Act to get the BBC to reveal who were the people present at a certain seminar whose advice led the BBC to decide to adopt a pro-AGW stance. The BBC described this decisive seminar as being graced by ‘some of the best scientific experts’. Newbery had a suspicion that there were many fewer experts and many more activists than the BBC made out. One out of the few – and I think that means one out of the one – people present at the seminar with views outside the consensus, Richard D North, said as much. Presumably North either had kept no record of the exact attendance list or had an obligation to keep it confidential.

The BBC really did not want to say. Representing himself, up against the BBC’s six lawyers, Newbery, not surprisingly, lost his case at the Information Tribunal. The fact that one of the lay judges had strong views against “deniers” probably didn’t help.

Though he had started an appeal, the point became moot when Maurizio Morabito of Omnologos found the list anyway by clever use of the Wayback Machine.

Watts Up With That, Bishop Hill, and Guido all have posts. Summary: Newbery was right.

They’re all there; Greenpeace, the New Economics Foundation, the Gaian branch of the Church of England, someone from Greenpeace China, bods from Stop Climate Chaos and Tearfund, Jon Plowman, Head of Comedy…

What? Head of Comedy? Yes. One of the aims of this series of seminars was to “take this coverage [international affairs, including climate change] out of the box of news and current affairs, so that the lives of people in the rest of the world, and the issues which affect them, become a regular feature of a much wider range of BBC programmes, for example dramas and features.”

Note that even some of the sciency sounding names and job titles listed are not exactly the hardest of the hard. According to the comments at Bishop Hill among the list there is a Senior Lecturer from the OU focussing on environmentalism and politics, a Geography PhD with an interest in conservation and human rights and a lucky undergraduate from Harvard specialising in documentary film making.

Why it matters.

Fun fact: all the four big-name resignations from the BBC over the last few days (Peter Rippon, Steve Mitchell, Helen Boaden and George Enwistle) were present. Someone somewhere (I’ve lost the link, I’m afraid) mentioned the Private Eye occasional feature “Curse of Gnome”.

Balen Report next, then!

Despite its obvious potential for oppression, for the first twenty years or so of its existence the Malicious Communications Act 1988 did not seem to do much harm. At least, if it did, I did not read about it. If I am wrong on this, tell me, but on the few occasions that I heard about prosecutions under the Act they seemed to be cases like this one where a man sent out emails purporting to be from the Foreign & Commonwealth Office in the aftermath of the 2005 tsunami falsely telling people that their relatives had been killed. That is certainly fraud, and something like assault, and I would argue that it is not a freedom of speech issue. “Malicious communication” seems a fair description.

You are not safe just because a monster sleeps. Circa 2006 the government rediscovered the Act and decided to give it some exercise. In the period 2006-2010 the number of people against whom proceedings were launched followed this pattern: 182, 251, 329, 507, 694.

The latest? Here is a story from the BBC: ‘Canterbury man arrested over burning poppy image’. He is not a Muslim apparently, and it is another reflection of the decline of free speech that my assumption that the BBC’s unnamed “Canterbury man” was left unnamed to conceal him being a Muslim was a perfectly reasonable one. In fact Linford House, 19, is a non-Muslim, white rugger bugger.

There is a good article by Ally Fogg in the Guardian: Arrested for poppy burning? Beware the tyranny of decency.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|