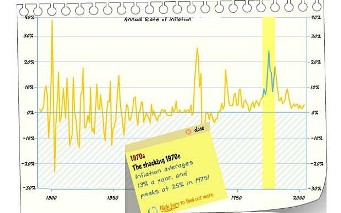

I was struck by this graphic, produced by the money printers at the Bank of England and reproduced in the Telegraph:

We are told (not least by the Bank of England) that deflation is the greatest threat to our well-being. But look at the Nineteenth Century. There’s no end of deflation there. And yet in this time they managed to build almost all of Britain’s railways (including three routes from London to Manchester), the Great Eastern, Crystal Palace, most of London, bring clean water and sewerage to the cities, introduce street lighting, make huge advances in science and medicine. and establish just about all the industries (coal, shipbuilding, steel etc) whose loss is so lamented, especially by people on the left.

OK, so I suspect a lot of those industries would have closed anyway but I fail to see how anyone could look at this graph and honestly claim that deflation was something to fear.

PS I now notice that the BoE does indeed talk about “Years of Deflation” between 1921 and 1931 and my understanding is that it was a pretty grim time. I would be interested to know if there’s a response to the implied claim that deflation is or was a bad thing.

‘Deflation’ simply means ‘low prices’. Consequently, it is neither a problem, nor a blessing in and of itself: it can be a symptom of something positive (such as increased productivity due to technological advancement), or something negative (such as decreasing demand as a result of stagnation).

My understanding is that in the UK there was a modest economic recovery up to 1929 which was then brought to an end by the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression. The 1920s were a time of economic boom in the US.

Its arguably more damaging in a legal environment that produces lots of sticky wage contracts and contracts that assume some level of inflation rather than deflation.

Alisa: “‘Deflation’ simply means ‘low prices’. ”

Hmmm.

Anyway, even in modern times we have experienced ‘deflation’. Not many people I know complain that their new higher specified computer is more powerful and costs less than their old one.

Even taking into account monetary inflation.

Similar with the motor market.

The cars we used to use in the ’70 (for example) were underpowered, poorly featured and relatively expensive.

There has been deflation in auto prices too.

Looking at the considerable oscillations in the ‘inflation/deflation’ rate in the first half of the 1800s, I must ask whether those shorter-term measurements have any reliability at all.

And (in line with APL’s comment above) what are inflation and deflation when the pool of goods on which they are judged is continuously changing and improving both in value for money and in sophistication. Perhaps we can judge the basic value of food by not starving – but warmth and shelter (accommodation) are significantly different, even from my childhood of only a few decades ago.

If one judges these things, plus local and international travel, healthcare and life expectancy: it is deflation all the way when measured in terms of the purchasing from a week’s work.

Best regards

I did say ‘simply’, APL. And, although I could be wrong, it didn’t sound as if the post was about monetary deflation.

Deflation/lower prices is a bad thing for governments, they get less sales tax.

Longer term they’d get less income tax also.

Deflation, let’s give it a try.

Like:-)

I think its as simple as:

Inflation erodes debt, deflation increases it.

Seeing as we’re pretty much all up to our eyeballs in debt (personal, corporate and state) then increasing the value/cost of our debt would be a pretty bad thing..

Neither inflation nor deflation have any real influence on debt itself – they only change the yardstick with which it is measured. Of course, the government owns the yardstick.

If in an economy there is stable prices, that is zero inflation, it is likely that there will be mild deflation. Efficiencies of manufacture and distribution increase in customer base and economies of scale might reasonably be expected to produce increasing value.

That is, the price of a manufactured good might go down in relation to the stable yardstick of the currency.

A couple of observations.

As Johnnydub explained, deflation increases the real size of debts. In the nineteenth century few people had debts of any kind. Indeed, borrowing money was considered a vaguely disreputable activity, an attitude that survived well into the twentieth century. Even as recently as 1914, the British owner occupancy rate was only about 10%; most people lived in private rented accommodation and, presumably, rents fell during times of deflation. By contrast, today a significant portion of the population is mortgaged to the hilt; add in other debts they owe and a period of deflation, with its attendant falling wages, would financially ruin them.

Meanwhile, it is interesting to note that for much of the time shown on the chart, Britain was on the gold standard. Perhaps the gold standard is not necessarily the guarantor of price stability its proponents claim it to be.

Ah, an interesting ‘discussion between Johnnydub and Alisa.

Johnnydub:

Alisa:

Personally, I think Alisa has the better of it. This is primarily because interest rates increase in times of inflation and decrease in times of deflation. That, itself, is an attempt by both sides of the market to be reasonable: the true value of money, and the cost of money, tries (in the sense of a free market) to be free of the artificiality of measurement, especially where that is measurement on a scale that is less than true according to the judgement of the market.

As Alisa writes: the government owns the yardstick. And clearly government is strongly motivated to manipulate the yardstick for the benefit of government, not least as they have some power to do so.

Best regards

I think that there’s a confusion in this discussion between money and the goods/services it (ideally) represents. The confusion may be on the part of one or more of the participants, or it may be just a failure of all of us to define the terms of the discussion.

I think most of us have got it pretty clearly. Inflation is when you have to ask your employer for more money to cover the rising costs of everything. Deflation is when you find you can buy more of everything without having to actually ask for more money.

And yes, deflation means long-term debt becomes more expensive, and inflation makes it cheaper. Thus having a “stronger currency” is a buzzword for deflation, which governments as holders of massive long-term debt don’t like, and having a weaker currency makes paying the government debt that much easier.

Deflation is not “simply low prices”. Yes, that is one consequence of deflation, but is neither its cause nor its definition. Furthermore, deflation is not the only cause of low prices. As others have already noted here, prices can fall for a myriad of reasons, notably improved efficiencies in production (better technology, etc.). Properly understood, deflation is a decrease in the money supply relative to the overall economy. If the money supply remains constant in a growing economy there would be a tendency for prices to fall (what Detlev Schlichter refers to as “secular deflation”). This is a good thing. As Schlichter put it in a comment on his blog,

Deflation harms debtors and benefits creditors (who get paid off in more valuable dollars). Yes, to some extent we’re all debtors, but the real debtors in western society are banks (which fund almost all of their operations with debt) and especially governments. That’s why they’re desperate to keep inflating the currency, at all costs, and will spread any lie (such as the claim that deflation is an unalloyed evil) or perpetrate any distortion (confusing the public as to what deflation really is) in order to perpetuate the current system. (Does anyone here really believe that governments and megabanks are looking our for our interests? If so I have a lovely bridge to sell you.)

In another post on his site Schlichter notes:

He spends much time in his book, and in his talk at the Adam Smith Institute last fall, debunking the notion that inflation is always bad.

There is no doubt that massive deflation would be extremely painful. But that’s because instead of permitting the constant micro-adjustments wrought by technology, etc., for a century or more our goverments have refused to permit those necessary corrections, pursuing instead an intentionally inflationary policy. The reasons for that aren’t important to this discussion, but the result of this massive cumulative distortion is as inevitable as it will be, shall we say, troublesome.* Governments will continue inflating the currency until it is completely unsustainable, resulting in hyperinflation and eventual collapse.

* “Life is pleasant. Death is peaceful. It’s the transition that’s troublesome.” — Isaac Asimov

Smited. Again. Sigh.

“Something there is that doesn’t love a firewall.” (apologies to Robert Frost)

Niall Ferguson may yet do so, but I am not aware of a treatise on A Monetary History of Westren Civilization, or indeed of the “World,” similar to that of Friedman & Schwartz in the U S.

Still, Deflation has both a monetary aspect and an economic transactions aspect – the correlations of which may vary by the extent to which Credits rather than Bullion serve as the major functions of “Money” (including the dreadfull store of value).

Deflation and depression are not synonymous though often contemporaneous. The rail systems of the U K and the U S were built by using credit, for example. Depending on whether it is generated by declines in the relative values of credits Deflation does not necessitate a decline in economic transactions, though they may slow. Other factors, such as tarrifs, can and do have depressive effects, as did mercantilism.

Consumer Credit which came into the banking systems in my infancy, and in the city of my youth, as The Morris Plan Banks, substantially changed the composition of credits in the monetary system. The factors of “private” debt and “Public” debt create a different “kind” of deflation from that of the historical past.

There is one strong reason why deflation can be bad in practice, even though it may not be bad in principle.

If the value of money rises, for your real salary to remain the same your nominal salary must decrease. If you live in a society that has powerful institutional arrangements designed to prevent that, such as entrenched union privilege, the minimum wage, benefit payments fixed in nominal terms, &c., the result is that wages rise above the market rate. This results in unemployment.

In fact such policies were aggressively pursued, especially in America but also elsewhere, during the Great Depression. In fact Hoover’s flagship policy in response to the Great Depression was to force (nominally it was voluntary – but on the basis that they would like the resulting legislation even less if they didn’t go along) companies not to cut wages in order to prop up “aggregate demand”.

It is possible in fact that this is why the Great Depression happened when it did, rather than in say 1830 – powerful unions and wage-fixing laws were not present at that time, and governments did not respond to recessions by strengthening such policies, so the market could quickly adjust with relatively short, sharp recessions.

It is very difficult to see how a system with deflation could be implemented today. Union privilege, at least in the UK, has been rolled back since the 1950s, but there’s a strong psychological block to decreasing nominal wages even if they’re worth the same or more in real terms.

PS I now notice that the BoE does indeed talk about “Years of Deflation” between 1921 and 1931 and my understanding is that it was a pretty grim time. I would be interested to know if there’s a response to the implied claim that deflation is or was a bad thing.

Britain’s return to the gold standard in 1925 was indeed disasterous – but only because Britain went “back on” at the old pre-war rate of US$4.86. Acknowleding the depreciation in sterling over the previous decade and returning to the gold standard at a lower rate would have spared much of the pain the British economy endured during the late 1920/early 1930s.

I’m sure many people who read this blog would be very interested to read Currency Wars by James Rickards: http://www.amazon.com/Currency-Wars-Making-Global-Portfolio/dp/1591844495

PS: I’m not James Rickards lol

As someone who runs a business that incurs costs before it receives income I can tell you the problem with deflation is simple:

Your costs only decrease with deflation after you have incurred them, while your planned income decreases before you receive it. Particularly if you have a business model with a cash-flow like mine. 12 – 18 months lead time from the start of production.

Now this doesn’t have to be a problem, especially for larger producers who can sell forward/future contracts at the start of production. However, smaller businesses and businesses selling direct to a consumer can have difficulties.

This is actually something that businesses already cope with all the time, especially those dealing with commodities that do, as we know, go down as well as up in price. So it is not the end of the world, just another pain in the ar$e thing to consider.

Clearly for all parties on both sides of the exchange SOUND MONEY is the best.

Everyone knows where they stand and it makes planning ones future business much simpler.

I would add that having a steady rate or deflation (or inflation for that matter) also helps planning wise. Although inflation can help with both debt financing and acts as a “margin” safety net.

Will someone please unsmite Laird?

I’d like to continue Johnnydub’s point – that if inflation erodes debt and deflation enlarges it in real terms, then the debtor wants to have inflation and the creditor wants to have deflation. And given human nature, that we want things we cannot afford outright, and we don’t want to work long and hard now so that we can enjoy the fruits of our labor later, why it’s easy to see that being a debtor is so much more attractive, especially if we can shift the rules to our advantage.

So we have reversed that age-old wisdom, “The borrower becomes the lender’s slave” (Proverbs 22:7) because the borrowers are becoming the 99% and can stick it to the 1% man.

And if I, as a 1% man, become weary of borrowers inflating away the value of my fiat money, and I go and buy physical gold, they can turn around and in the name of “national security” get the government to confiscate my gold. Heads they win, tails I lose.

Or is this too simplistic?

Laird, what I meant was that under inelastic money supply, deflation becomes synonymous with lower prices.

Neither deflation, nor inflation affect the size of the real debt, what they do affect is the size of debt in monetary terms. When the money is real (i.e. money supply is inelastic), the monetary debt serves as a realistic representation of the real debt (i.e. goods/services exchanged for money). When the money is funny, the real debt is forgotten, and instead both sides of the original loan agreement are essentially forced into a new one. This new “loan agreement” has nothing to do with the original agreement (or its real size), other than using it as an excuse to extend favors to one party to the original loan agreement over the other by the government.

“deflation” can mean lower prices (of course a “price index” is a flawed concept – but I am not going to deal with all that just now) or (more properly) it can mean a decline in the money supply.

A fall in prices can occur without any fall in the money supply – by people finding better (cheaper) ways of producing goods and services.

However, a rapid fall in prices (a crash) is normally associated with a big fall in the money supply.

Now how can this occur?

Does it mean that bad elves (like elves in Old English mythology) go about buring notes and melting down coins?

No.

What it means is a collapse in BANK CREDIT (“broad money”) – i.e. bank loans (and other such) that were not from real savings in the first place (so there are not the notes and coins to “back” them).

A normal human mind would consider that fraud has taken place (to produce vast amounts of such loans that are not from savings – i.e. money that DOES NOT REALLY EXIST), but statutes and court judgements are carefully written so that the above is not considered fraud.

Anyway – the Bank of England (like the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank and….) is concerned that bank credit (“broad money”) will collapse – so it pumps up the money supply (the types of money that it controls) and sends this money out into the banking system – in a desperate effort to stop this happening.

That is why an “expansionary monetary policy” does not involve the Central Bank creating money and giving it to ordinary folk. The point of it is to prevent a banking collapase – and with such a collapse a massive “deflation” of the credit money bubble. So there is no point giving the money to Mr Smith or Mrs Jones – the money must be sent to the bankers, because it is their credit bubble (“broad money” that is in danger of deflating).

That is the real reason the word “deflation” is used – think of how a balloon “deflates” when one sticks a pin into it.

Of course banks would not build credit bubbles on this scale without Central Bank intervention in the first place.

Even J.P. Morgan and the other titans of his era (who were considered, and considered themselves, to be the ultimate in daring) only produced between two and three Dollars of credit for every Dollar of hard cash.

After the introduction of the Federal Reserve system this went up to 12 Dollars of credit for every one Dollar of cash by 1929 (and remember the World War One credit bubble was liquidated in 1921 – the bust of 1921, so this was pure Ben Strong of the New York Federal Reserve credit bubble orgy).

Alan Greenspan was the main force behind the expansion of the money supply in the 1990s and 2000s (with the British Bank of England, and so on, following on behind). Every time the credit bubble looked like it was going to burst – he came along to “save the world”, by yet more monetary expansion.

And B.B. (if only that was Bilbo Baggins) of the New York Fed and the Bank of England people (and the Eurpean Central Bank people) all regard the credit bubble (the banks and other financial institutions) as sacred.

They will do just about anything to save them – to prevent the credit bust (what they really mean by “deflation”).

However, there is one extra factor to be considered…..

The distortion of the basic economy itself (the capital structure) – it is now so twisted that it looks like a corkscrew.

The Central Bank people do not bother there heads about such silly “Austrian School” stuff – after all they have a sacred credit bubble (I mean a “financial system”) to save.

However, the distorted (utterly twisted) nature of the fundemental economy will make itself felt – more and more.

“But how would you save the financial system?”

I would not try to save it.

As a boy (and I mean that – yes I was so “sad” that decades ago I walked to school thinking of stuff like this) I thought of the Bank of England printing money (litterally printing it – not doing the stuff they do) and GIVING (not “loaning”) it to the banks – ON CONDITION THAT THE INVERTED PYRAMIDS OF DEBT WERE ENDED FOR EVER.

No more “fractional reserve banking” – where the “fraction” turns out to be “one hundred tenths” or whatever (i.e. far more is lent out than was ever really saved – not how most people think “fractional reserve banking” works).

However, I no longer believe in all that.

The financial system is so complext and so full of people who operate on different principles (I am trying to be polite) that any deal would be twisted and broken.

So – let it go.

It is going to go anyway – the collapse can not be long delayed (whatever the Central Bankers do), so let the collapse be NOW – so that people have a chance to rebuild an economy (whilst there is still a chance of rebuilding an economy).

“But Paul does a collapse mean that prices will go up or go down?”

Errrr I suspect it means something rather more radical – something that makes that question beside the point.

If things go well then people will be buying goods and services in gold and/or some other commodity money (such as silver – or perhaps copper).

And if things go badly – the main currency will be ammunition.

Re: P M Org Overview:

About the only thing missing is an aphoristic query: Can there be deflation where there has been no inflation?”

Then there is the “new” jargon term Disinflation.

It turns, as P M implies, on the nature of the credits.

The credits “created” (directed?) by J P Morgan et al. went to the building, aggregating, augmenting and operation of productive assets (many not easily transferable, hence illiquid). The goals were production, and to some extent distribution; any, if not all, of which would return five-fold the credit outlays- thus more than satisfying time preferences.

What have credits, particularly those that serve a monetary function, been created to achieve?

(a) Production enhancements

(b) Distribution efficiencies

(c) Political power or influence

(d)Cost spreading of capital outlays over future users

(e)Consumption

(f) [the fatal letter] Other – or insert your own.

“Can there be deflation where there has been no inflation?”

The short answer is “yes”; there is no necessary correlation between the two. The more interesting answer is to ask why the question; do you really think there has been no inflation? Surely you don’t believe that the CPI is a valid measure of inflation, or (for that matter) that there is any validity whatsoever to the grossly distorted CPI figures which the US government disseminates? The ones for which they regularly “adjust” the components to eliminate those inconvenient things (food and housing, for starters) upon which most people spend the bulk of their income? Take a look at the US adjusted monetary base and tell me you don’t think there is massive incipient inflation baked into that graph. Just because the dishonest CPI numbers aren’t showing much “inflation” doesn’t mean that it’s not there.

L-

Au Contraire, there has been continuous inflation, of course.

My note was to reflect back on the chart source and its implication that deflation results from or is correlated with “depression” or stagnation in economic transactions – trade.

While inflation, extant or prospective, is generally seen in the symptomatic expressions of prices, whose validity as informative signals for a market system is diminished, the causes of those symptoms lie in the uses of credits for the functions of money; and to a large extent in the objectives of those uses.

posted

Apologies for the misunderstanding, RRS.

There has been a vast amount of inflation – the increase in “broad money” (bank credit) has been vast over the last few decades. Do I have to explain again that “inflation” is not “price indexes” (particularly rigged ones – i.e. ones the government is in charge of) – or, indeed, prices in the shops at all?

And the recent increase in the “monetary base” (the sort of money Central Banks create) has been on a vast scale also (it was occuring all the time – but since 2008 it has been increasing on a vast scale).

The Central Banks (Federal Reserve, Bank of England, ECB and so on) have been increasing the monetary base (“narrow money”) out of fear that bank credit (“broad money”) will collapse.

This collapse is what they mean by “deflation”.

I have now explained all this twice.

Being a bad tempered middle aged man, I will not explain it a third time.

Lets just have sound money.

per PM

Precisely the point made, I think, by Humpty-Dumpty.

When they use a word, it shall mean (for their purposes) whatever they shall intend it to mean.

The banking systems buy, sell, swap, create and consume credit, not bullion or specie or much else in the way of “hard” assets, other than real estate. They have now reached the point where they are essentially state-created or state (politically)-sponsored monopolies in those credits serving the functions of money.

Perhaps our heavy metal friend Ian Dodge could do a slightly modified version of an old Blue Oyster Cult song: “Don’t fear de flation…”

Hey, it’s near dawn and I’ve been working all night!