I attended Alan Boyle’s book release signing tonight amongst a group of familiar faces. As such things go, this one was a great deal of fun as attendees were actually rather familiar with the material and the debate to which Alan has taken the ‘Pluto is a Planet’ side. If you are interested in the history of the whole debate over what is a planet according to astronomers, this is a worthwhile addition to your shelf.

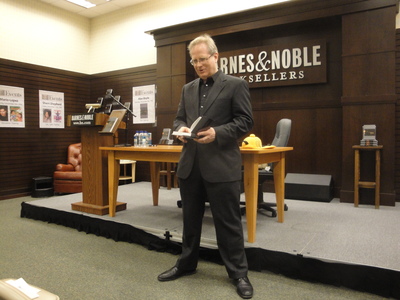

Alan Boyle reading from his newly released book, “The Case For Pluto” at Barnes and Nobles in The Grove in LA.

Photo: copyright Dale Amon, All Rights Reserved

Alan’s book release also presents me with the excuse I have been waiting for to throw in my tuppence in this ‘debate’.

For astronomical purposes, the reclassification of Pluto to officially be a scare quoted ‘Dwarf Planet’ is useful. I can also admit their classification of every element other than Hydrogen and Helium as a metal might also be useful… to them. On the other hand, neither classification is of much use to anyone else. Oxygen might be an astronomer’s metal, but to one like myself whose undergraduate degree was in Electrical Engineering, this method of sorting elements is rather silly. astronomer’s definition of planet is likewise rather worthless outside their discipline.

For those of us who look upon space as a place for settlement, commerce, and a source of resources to feed a solar system wide industrial economy, knowing whether a body clears its orbit of other matter is a “So what?” issue. Settlement and industry have different concerns and will most likely require a more complex system of classification. A planet with a thousand kilometer deep atmosphere that gradually turns to a liquid and then a solid phase is not useful for the same things as a body with a rocky surface. There may be temperate bodies out there covered with hundred mile deep oceans of water; there may be ones with molten rock surfaces. Each presents unique characteristics to the future explorer or industrialist.

From my point of view a planet has sufficient gravity to make it round-ish. Ceres and many of the new bodies outside of Pluto’s orbit are therefore planets in my book. I propose that just as Electrical Engineers ignore the astronomer’s definition of metal, the rest of us should ignore their definition of planet as well.

I think maybe the important distinction is actually between the gas giants and the small and rocky planets. There is clearly a qualitative difference between one of those and the smaller, rocky planets. However, frankly the transition from Mars and Earth via Venus and Mercury to Pluto, Ceres etc is a more gradual one, and drawing any kind of line is difficult. “Anything roundish” is a fair enough rule, but of course this leads to “How roundish?”. Any choice is going to be more or less arbitrary, which is why we are going to continue arguing about this.

I always liked the astrophysics version of chemistry – hydrogen, helium, metals because there was a lot less of it and chemistry is wank anyway.

Tomatoes being fruit & not vegetables never stopped them being placed beside the lttuce & cucumbers in greengrocers.

When I was growing up, Pluto was a planet. We weren’t all mistaken, it actually was a planet. That’s because the classification is somewhat arbitrary.

Let me ask this. Could those same stuffy Astronomers theoretically get together and call Mercury a dwarf planet even though mankind has known it as a planet since antiquity? If no, then why can they demote Pluto? Because it was known as a planet for a shorter lenght of time?

Pluto is a planet. I have books (published when I was a kid) to prove it.

Who trusts astronomers anyway? They use i to represent the square root of -1 when every right thinking person knows to use j instead to avoid confusion with electrical current i.

Yes, quite, AbuZuzu.

i is for current, meaning we avoid confusion with inductance by calling inductance L.

I admit to finding the whole “is it, isn’t it” debate rather surreal, particularly when it comes to the argument of a planet needing to sweep its orbit clean, in order to qualify.

After all, if Pluto isn’t a planet, then by this argument neither is Neptune, as Neptune has thus far failed to sweep its orbit clean of Pluto ;-).

The pointlessness of the public debate is to a great extent based on an opinion that the IAU classification matters to anyone outside of the IAU. It doesn’t. There will be other classification schemes and there will be common usage. If you are an asteroid miner of 2110 Ceres and probably even some of the less rounded bodies will be ‘planets’ to you. If you are an explorer of 3010 you might have as many words for planet as Eskimos have for snow.

The way around this debate is to admit that the astronomy guys have their own special needs and they are different from those of the rest of us.

As Boyle notes in his excellent book, the IAU definition is not even agreed upon by a consensus within the astronomy community. Pluto is still a planet. Only four percent of the IAU voted on the controversial demotion, and most are not planetary scientists. Their decision was immediately opposed in a formal petition by hundreds of professional astronomers led by Dr. Alan Stern, Principal Investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto. One reason the IAU definition makes no sense is it says dwarf planets are not planets at all! That is like saying a grizzly bear is not a bear, and it is inconsistent with the use of the term “dwarf” in astronomy, where dwarf stars are still stars, and dwarf galaxies are still galaxies. Also, the IAU definition classifies objects solely by where they are while ignoring what they are. If Earth were in Pluto’s orbit, according to the IAU definition, it would not be a planet either. A definition that takes the same object and makes it a planet in one location and not a planet in another is essentially useless. As for roundness, the issue isn’t whether the object is a perfect sphere but whether it is large enough to be pulled into a spherical shape by its own gravity. The latter is a characteristic of planets, not asteroids, and Pluto very much meets that criterion.

” . . . this is a worthwhile addition to your shelf.”

No disrespect intended to Dale, but my bookshelves are sagging under books, far too many of which I haven’t yet had a chance to read (or to read adequately), and there are scores of other worthy candidates begging for inclusion. Frankly, I don’t see this one making the list. And with all the other, more pressing, public policy issues clamoring for our attention, I don’t think this is a debate worth entering.

Laird, YMMV… My shelving propensities may well be based on a different relevance classification system than yours 😉

🙂

It seems to me that the orbit-clearing distinction is actually especially important if you want to settle on a body, especially if you are setting up a long-term civilization. Will you have warning before a gravitationally-bound object hits you, or will you be beholden to laws of random billiard balls? Will your orbit be stable over time or might you meet another large body that could fling you inwards or outwards?