About a year and a half ago, Terence Kealey gave a talk at a Hobart Lunch at the Institute of Economic Affairs arguing that a world without patents would be more innovative. Dr Kealey is a biochemist who is Vice-Chancellor of the University of Buckingham and the author of The Scientific Laws of Economic Research.

It was one of the most interesting events I have been to at the IEA, and the audience was very much split which made for an entertaining Q&A session. I disagreed with Dr Kealey at the lunch, but I recognized there was something to what he said. The lunch was something of a life-changing experience because I have subsequently moved towards his position, though I’m not there yet.

One of the most difficult aspects of thinking about a world with less or no patent protection is that it is so hard to imagine. When thinking about a Britain with a denationalized National Health Service, you can visit mainland Europe or America and see how systems work in other developed countries. Country comparisons aren’t so easily available when it comes to patents.

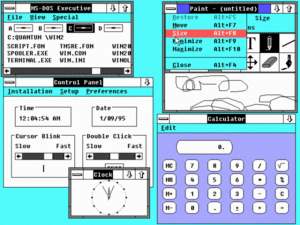

But one market – that of software – clearly shows that fast innovation can occur without patents, at least in the area of software. If software patents had existed in the US from day one, and if there had been a culture of patenting everything, we might live in a very different world today. We might sit in front of our computers today and see this:

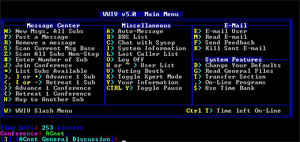

And people would pronounce in public: “Thank goodness that we have software patents. Just as property rights in physical property enables economic development, software patents enable software development.” And they would post articles to that effect on the internet, known in this alternative reality as The Microsoft Network, which might look like this:

And everyone would be thankful that we have a system that clearly and undeniably promotes innovation.

The point of patents has nothing to do with promoting or discouraging innovation directly, the point is to let someone reap the financial rewards of a good idea, and by doing so encourage people to have good ideas.

We need to be careful to distinguish between patents specifically (and I do think that the system as it currently exists has many warts) and protecting intellectual property in general.

It often strikes me as odd that the people who defend patents are often opposed to state interference – yet the patent IS a state interference in the market – whereas those who oppose them are often much more pragmatic and rational about state intervention.

Similarly, with the concept of the limited liability corporation, which is a state interference/distortion.

EG

EG,

Couldn’t have said so better myself. The vast Ministry of Defence patent unit, formerly based at the Empress State building in West Brompton, existed primarily for just one purpose – to analyse all filed or pending patent applications and see what military use could be generated from the product.

As for the image of the early Windows GUI , if software patents had been enforced then its extremely unlikely that either Jobs or Gates would have been allowed to use Xerox’s Palo Alto Labs research and thus you probably would not have ended up with the ‘desktop’ system. Of course Jobs/Woz would have found another way round and Gates would have then undoubtedly ‘copied’ that system.

Alex, could you do another post outlining Dr Kealey’s arguments? There would seem to be some points for and against such a reform, but an elaboration might be in order for the legally and economically illiterate among us.

Julian,

Steve Jobs bought the rights to tour the Palo Alto labs and to use what he saw. And Apple (John Scully I think) sold Microsoft the right to copy them.

Alex, thanks for illustrating the difference between Economic Reasoning and Accounting Fallacies. No achievements that are seen can serve to justify anything until they are compared with the alternative achievements that cannot be seen but only imagined (thank you, Bastiat). And as of patents in particular, I still recommend Patents are an Economic Absurdity.

That was shameless plug day.

Steve Jobs neither paid for nor stole Xerox PARC’s research — XEROX invested in Apple.

I don’t think that it’s fruitful just to say that patents constitute state interference in a market. It is through the state that we define property rights, and so why not intellectual property rights too? It is always an open question how best to do it. The views of a reflective biochemist are likely to be worth listening to, because drug patents are such a big deal.

Euan makes an interesting point about limited liability. Some libertarians, like Sean Gabb, for instance, have argued that such laws should be abolished.

Steve Jobs neither paid for nor stole Xerox PARC’s research — XEROX invested in Apple.

The payment Apple negotiated with Xerox PARC was to get in on Apple’s IPO. IIRC, Xerox PARC netted a few tens of millions in profit on the deal- in the 70s, that was real money.

I don’t think that would be a good idea.

Limited liability is a problem in the sense that it permits investors to escape sanction for wrongs done with their money and insulates the investor from the lack of wisdom of his investment (to a certain extent). On the other hand, it is a boon in that it permits more speculative and risky ventures than would otherwise be embarked upon, for these same reasons, and you can’t have the reward without first taking the risk. I think on the whole that incorporation with limited liability is a net good thing to have since otherwise we would unlikely to have progressed as far or as fast.

It is, of course, another example of state interference in the market making greater progress possible. It is extremely stupid, IMO, to decry ALL state intervention on the basis that SOME (or if you must, MOST) state intervention is counterproductive. This is hasty generalisation, a trap into which ideologues of all stripes do, most amusingly and incredibly frequently, fall.

EG

I can imagine a freely developed stateless form of limited liability developing.

All contracts and dealings with my firm would state or imply that it was on the understanding that my liability was limited to £xx,xxx. It would then be up to you to decide wether that was an acceptable basis on which to do business with me. Risk would be at your own peril.

No doubt insurance and credit risk analysis would be available as it is now from agencies.

What Sean might argue is that there is no need for the state to determine these arangements.

[I am not familiar with his arguments, he may already say this – or not. You never know where Sean’s imagination will take you.]

paul d s,

Is it not a tad more complex than that?

If you have a maximum liability of say £1,000, but you have 1,000 transactions, then your maximum aggregate liability is £1 million. Suppose, though, that your investors have only stumped up £750k to fund your company. Where does the other £250k comes from? Who enforces that law, and on what basis does everyone have to agree that their authority to enforce it is valid?

EG

It is, of course, another example of state interference in the market making greater progress possible. It is extremely stupid, IMO, to decry ALL state intervention on the basis that SOME (or if you must, MOST) state intervention is counterproductive. This is hasty generalisation, a trap into which ideologues of all stripes do, most amusingly and incredibly frequently, fall.

Then it took Ludwig von Mises about 1000 pages of Human Action to make this ‘amusing’ and ‘hasty’ generalisation. What a twit he must have felt.

Much as Marx should have done after going on for hundreds of turgid pages, only to be wrong.

Just because it’s in a book written by some bloke with a German name does not mean it is correct.

EG

Euan, I won’t answer for Sean Gabb, but in my view Paul ds’s point is quite interesting in that it may not be necessary for the state to legislate the existence of limited liability companies for them to exist. If such things are so self-evidently sensible, then it is usually unnecessary to have state intervention to bring it about. Intelligent self-interest usually does the trick.

I’m not saying that Mises was necessarily right, just pointing out that his view was scarcely a ‘hasty’ generalisation, it was the result of lots of very deep thinking. (As was Marx’s for that matter) It is you who make the hasty generalisation in assuming all who decry state intervention are making an ‘incredible’ and ‘amusing’ error.

As in the famous private sector eradication of cholera, the voluntary market adoption of food and drug purity standards and the phenomenal success of private monetary systems in producing stable currency, perhaps?

More seriously, your general point is valid enough, but there are cases where it is necessary to have state intervention to bring things about. It’s best not be dogmatic and insist that either only the state can do something, or contrarily that the state is not necessary for anything.

The idea that state intervention is always wrong is a hasty generalisation NOT because it is posited too quickly (this is not what the phrase means), but because it takes the general postulate (state intervention is often or even usually counterproductive) and assumes with inadquate thought and no consideration of the contrary examples that it is therefore ALWAYS counterproductive. You can take 20 years to reach your conclusion, thinking terribly deeply all the way, but still be guilty of hasty generalisation.

There are examples of successful state intervention, so the thesis is demonstrably false as a GENERAL thesis, but may still be valid in SPECIAL cases.

Incorrect. I am amused by people who insist that it is ALWAYS wrong, in the face of real world data that shows the contention is manifestly incorrect. Even if it is usually wrong, it is not always wrong.

EG

“yet the patent IS a state interference in the market “

That is glaringly false.

If patents are recognized as property, and if it is agreed that the state’s legitimate function is to protect property rights (otherwise no society can exist), than state’s role in patent protection is it’s rightful task, not “iterference”. That above is a somewhat demagogical pronouncement.

The late 19TH century leftie-anarchists claimed that state’s protection of property rights was oppresion, it enabled the capitalists, owners of the means of production, to keep exploiting and oppresing the poor proles, while the state forcefully protected the capitalists (i.e. their property rights).

One should beware of such loose juggling of words and concepts.

The idea that state intervention is always wrong is a hasty generalisation … because it takes the general postulate (state intervention is often or even usually counterproductive) and assumes with inadquate thought and no consideration of the contrary examples that it is therefore ALWAYS counterproductive.

Here you are again making all sort of wild and false assertions. Certainly not Mises and practically no other outright opponents of state intervention make any such errors as you describe.

Indeed very few people hold the view that all state intervention is wrong and those that do come to their conclusions not from making the sort of mistakes you describe. Nearly all are professional Austrian economists or philosophical libertarians and they have spent many years testing their arguments against the strongest alleged counter arguments.

They may not necessarily be right but you seem falsely to think that you can dismiss their views merely with a fatuous accusation of slack scholarship. You still cannot see that it is you who is guilty of hasty generalisation and you do it all the time.

Here is another example:

those who oppose them (patents) are often much more pragmatic and rational about state intervention.

Wrong; the most vigorous opposition to patents comes from the no-compromise free market purists associated with the Ludwig von Mises Institute.

It may be a legitimate interference, but the grant of a legal monopoly is nevertheless an interference in the market by the state – patents would not exist without a state enforcement system to compel people to observe them. After all, is it not libertarian received wisdom that monopoly can only arise by state interference? A patent is a monopoly, therefore it must be state interference.

Banging on about it being legitimate is mere linguistic hair splitting and serves no purpose other than to provide the determined anti-statist with some nebulous justification for accepting that there are times when state action achieves what he wants. Why not just accept that not all state action is bad?

EG

It’s not an accusation of slack scholarship, it’s just an error in the reasoning within that scholarship. People make mistakes, even if they do have German names.

Marx worked and thought long and hard to come up with his ideas. They are generally accepted these days to be wrong, at least in the large scale, but this has nothing to do with the length or intensity of study and thought that went into them. Similarly with von Mises – plenty of work, but nevertheless a wrong conclusion. He was only human, you know.

And how exactly does that refute the idea that people who oppose patents are OFTEN (note, not EXCLUSIVELY) of a more pragmatic disposition?

EG

No, you specifically accused Mises and the non interventionists of inadquate thought and no consideration of the contrary examples .

I don’t deny Mises may have made mistakes but it is simply false and intellectually lazy of you to make the accustaion of ‘hasty generalisation’. He did not make hasty generalisations or fail to consider counter arguments. Similarly you are right to say that Marx’s ideas are now considered false, but that is becasue his theoretical errors have been carefully and painstakingly exposed, not because some halfwit accused him of making ‘hasty generalisations’.

And how exactly does that refute the idea that people who oppose patents are OFTEN (note, not EXCLUSIVELY) of a more pragmatic disposition?

Your qualifier of ‘often’ does not save your statement from being false and misleading.

He patently did, since his thesis is refuted by real-world examples available at the time of writing and before. He either ignored them or didn’t know about them (which is unlikely). It’s not a counter-ARGUMENT that he didn’t pay attention to, it is concrete FACTS. Thus, there was an error in his reasoning caused by a failure to take account of contrary data, either wilfully or accidentally. Either way, it’s a mistake, and the type of mistake is hasty generalisation.

So he made a mistake. Big deal, people do.

But your illustration of a single group who don’t meet my non-exclusive criteria doesn’t exactly mean much, does it?

For my statement to be false and misleading, I think you would have to provide evidence that a pragmatic approach to state intervention is a rare thing amongst people who oppose patents. I’m not holding my breath.

All you’ve done is point to a single group who aren’t pragmatic and suggested that this refutes my contention. Tough luck, but it doesn’t. You’re arguing from the specific to the general without evidence, aren’t you? Hmm, do you think that could be another hasty generalisation?

EG

He patently did, since his thesis is refuted by real-world examples available at the time of writing and before. He either ignored them or didn’t know about them

No, he (and nearly all others who have written on this subject) considered all of strongest available counter aurguments and then carefully and specifiacally explained why they did not in fact work. I don’t know what so called ‘concrete facts’ you have in mind (if, indeed, any) but they will have been carefully assessed and rejected for a clear and given reason.

Mises, and the others, may have made errors in their theoretical reasoning, I do not dispute this, but it is utterly false for you to allege that they either wilfully ignored or were unaware of the strongest counter arguments. I suspect that you have never read the work of a single one of these theorists you are so cavalierly dismissing.

As for your silly statement that the opponents of patents are often the most pragmatic about state intervention. What is the point of it? It is just an ill conceived and hasty assumption on your part which you would not have written had you been aware that the people who make the most sustained and vigorous intellectual case against patents are free market purists.

Obviously the state doesn’t *always* !@#$ things up, and there are certainly instances where it had benefitted society. The question though is whether these occasions are worth the price of all the other instances that are counter productive. In a perfect world you could count on the government for the good ones, and have them but out the rest of the time, but I think we can all agree that just about any government’s nature is to expand in size and interferrence… “give em and inch etc….” So the question that should be asked is are the states past and future “triumphs” going to out weigh the cost rest of the package.

Wow… what an awful piece of text I posted there….. sorry about that.

It may be a legitimate interference, but the grant of a legal monopoly is nevertheless an interference in the market by the state

Property rights in general are either granted by or defended by the state. Property rights can also be described as giving the property owner a monopoly on his property.

Thus, if I own a parcel of land, the original title to that land was probably granted by the state in the distant past, my rights in the land are defended by the state in the present in the form of laws against trespass and the institutions to enforce those laws, and my property rights pretty much give me a monopoly on the use and enjoyment of my land.

Are we then to conclude that all property rights are an interference in the market? The characteristics of patents that so many like to complaing about seem to me to be shared by property in general.

And don’t start with an argument that you can own a material object but you can’t or shouldn’t own something intangible and infinitely reproducible. Real estate is defined by its boundaries, which are intangible and arbitrary. Stock in a company is intangible, and can be reproduced indefinitely without taking one share away from current owners.

True, reproducing shares of stock dilutes the current owners and thus erodes the value of their stock, but it does so in a fashion precisely analogous to the way reproduction of intellectual property erodes the value of that property to its creator.

I don’t see how intellectual property of any form can properly be considered to be property. There is no scarcity involved with any idea.

My use of somebody else’s idea does not prevent that person from using that idea, whereas my use of somebody’s car prevents that person from using his car.

Freedom loving folks ought to recognize that all forms of intellectual property law, and especially patents, are nothing more than a government priviledge that interferes with actual property rights.

My use of somebody else’s idea does not prevent that person from using that idea, whereas my use of somebody’s car prevents that person from using his car.

Your having a picnic on my front lawn doesn’t prevent me from living in my house, either. Does this mean that your picnic should not be a trespass?

Scarcity has never been, as far as I know, one of the roots of property. Exclusivity, on the other hand, has.

The fundamental property right is the right to exclude. Thus, you are not allowed to use my property even if your use does not interfere with mine. It is still theft if you take my car and return it before I need it again. It is still trespass even if your presence on my land doesn’t deny me the use of my land. The reason is that your “borrowing” of my car and my land is a violation of my exclusive rights, not because your use interferes with mine.

Intellectual property not qualitatively different from any other kind of property, but is merely the extension of the idea of exclusive rights to a new class of intangibles.

Any intangible is infinitely reproducible, but reproduction of a piece of intangible property reduces the economic value of each item of intangible property. This same principle applies to money (where it shows up as inflation) and financial instruments (where it is called dilution). Simply because you can print off another stock certificate without taking mine from me doesn’t mean you haven’t taken value from me. The same is true with ideas.

RC Dean,

If I have a picnic on your front lawn, then that prevents you from using your property as you see fit, and is properly labelled “trespass”, even if you are sleeping at the time and are not using that portion of your lawn. This is not in dispute here.

Forgive me for the confusion I caused. I normally also use the word “exclusivity” when writing about property rights.

Intellectual property is qualitatively different. One’s use of an idea DOES NOT prevent somebody else from using that idea, whereas one’s use of my car prevents me from using my car.

If Joe invents a new type of mousetrap, and Sally finds out about the idea and builds a similar mousetrap, she is not infringing on Joe’s rights at all. Joe still has his original idea and can still use it as he sees fit.

If I print out a fake stock certificate on my computer and sell it as a genuine piece of a company, I am engaging in fraud. That would properly be labelled as theft.

Using somebody else’s idea is not theft as the original creator of the idea still possesses his original idea.

If I have a picnic on your front lawn, then that prevents you from using your property as you see fit, and is properly labelled “trespass”, even if you are sleeping at the time and are not using that portion of your lawn.

Not necessarily. If I am out of town, and there is no possible way that I could use my property while you are picnicking, it is still trespass. The key to a violation of property rights is denial of my exclusive rights to my property, not interference with my use of my property.

One’s use of an idea DOES NOT prevent somebody else from using that idea, whereas one’s use of my car prevents me from using my car.

The quick answer, and really the true one, is that your copying and use of an idea most certainly prevents the owner of the idea from using it to make money.

At a more principled level, your use of someone else’s property is a violation of their rights regardless of whether it deprives them of the use of their property. Because you can violate someone’s property rights without depriving them of the use of their property, it is irrelevant whether your use of my idea prevents me from also using that idea.

Once you recognize the core concept of property rights is exclusive control over the propery rather than the right to use the property, the main objection to intellectual property rights in principle goes away. That’s not to say there isn’t a better way to implement IP, just that the fundamental objection to it is based on a basic misunderstanding of what all property rights are about.

Its not about use, its about exclusivity. And your copying of my idea without my permission violates my right to the exclusive use of my idea.

Using somebody else’s idea is not theft as the original creator of the idea still possesses his original idea.

But you have taken from him some increment of the economic value of the idea. If you deprive me of the value of my intangible property by distributing copies of it, how have you not taken something from me, even though I still possess my original (intangible) property?

If I print out a fake stock certificate on my computer and sell it as a genuine piece of a company, I am engaging in fraud. That would properly be labelled as theft.

My example of a diluting stock issue assumed that the new stock would be valid. Of course, if you just print it off on your own, it isn’t. Why is that, though? If the keystone of my property rights is the uninterrupted possession and use of my property, the issue of new stock by any schmuck with a printer should be perfectly legal, because it doesn’t interfere with my exclusive possession and control of my stock.

However, it is of course a violation of my rights to the company. And for exactly the same reason that your copying and distribution of my ideas is a violation of my intellectual property rights.

Whether you distribute shares of stock in my company or copies of my valuable idea, I believe most people would say that you have taken something from me, even though I still own the exact same stock and the exact same idea as before. The reason they would say this is because, where my stock or my idea was worth x before you distributed free copies of it, it is worth less than x after you did so.

Of course, we don’t allow just anyone to run off shares of stock, because doing so takes value from the legitimate shareholders. However, letting just anyone distribute valuable intellectual property takes value from the legitimate owner in exactly the same way.

They both still have exactly the same stock or idea that they had before. All they have lost is its market value.

Ahem, getting back to the point of the post, rosignol said:

“The point of patents has nothing to do with promoting or discouraging innovation directly, the point is to let someone reap the financial rewards of a good idea, and by doing so encourage people to have good ideas.”

Well, sort of.

Actually people who have good ideas need no encouragement. What these people need is a scheme to encourage them to eventually get the results of these ideas into the public domain.

The alternative is the trade secret approach. While this is difficult in general (protecting trade secrets) it is, at least in some cases, possible.

The result of the trade secret approach is that the ‘secret’ of Damascus steel has been lost along with many others such as the method of creation of the Stradivarius violin.

The patent system is a perhaps flawed answer to the defects of the trade secret system but something is needed, from a public policy point of view, to prevent the loses inhrent in the trade secret system.

There are indeed very serious flaws in the patent system which permit, if not encourage, gaming the system in ways that seem very much like fraud.

Feel free to have whatever theoretical problems with the concept that may occur to you, but I really don’t object to people getting paid for what they do. A properly administered patent system is one way of making sure that that happens.

My only question is one of implementation: what is the appropriate period of exclusive rights? When does it make sense for an invention to enter the public domain, so that either further improvements can be made, or more efficient methods of production may be employed? This is a political question & should be thrashed out in public.

Instead of patents, which are fairly short in their terms, why not focus on copyrights? That damned rodent Mickey Mouse is likely to achieve immortality if Disney keeps making “campaign contributions” (which, being translated, signifieth bribes). I’d like to launch a torpedo at Steamboat Willie.

Unfortunately overlooking in the process the unpleasant reality that some of them do, in fact, work in the real world even if they theoretically shouldn’t. This is an error, however much you may seek to defend the Prophet of Wisdom from the charge of fucking up.

I think one of the major problems with the the libertarian (esp. Austrian) view is that it discounts real-world data when that data disproves the theoretical contention. Indeed, some Austrians specifically say that real world data can be safely ignored because they have PROVED logically that they are right. There never seems to be any explanation from them of why it is that things they say cannot happen do actually happen.

This is, IMO, an extremely stupid methodology, akin to asserting the “fact” that God undoubtedly exists because He has been “proved” to by various logical means. It is, in sum, a religious outlook, just as blinkered as that of any strict church. It is no basis on which to run anything, as history has proved repeatedly, painfully and often bloodily. Why people persist in thinking that maybe THIS time we’ve got it right because this is a better book/author/guru is beyond me.

It is also unwise to assume that because some bloke may have been right about several things then he is necessarily right about everything. This is a common human weakness, but it’s still wrong.

EG

Surely there is another way to attack the issue of patents: polycentric law. If patents are such a great way to stimulate innovation – which seems to be at the core of the issue – then different types of patent laws, with different costs, time-expiries, etc, would demonstrate whether this is true or not. Some areas might not have patents at all. Over time, an “optimal” patent system would tend to dominate in a given area as the one most people wanted to use. This is rather like the evolution of bankruptcy protection rules in the U.S.

Sometimes we have to accept that there is no “ideal” rule out there, but legal evolution is a way to fumble towards some kind of best-practice approach. This is, of course, an insight of the Austrian school that the tiresome Mr Gray seems to hold in contempt.

Like one or two commenters above, I profoundly disagree with Gray that the granting of property rights where none existed before counts as intervention. I thought defence and definition of property rights was an essential feature of a liberal, free market order.

Mr Gray holds in contempt not the insights of the Austrian school, but their hubristic methodology of assuming that logical proof is sufficient and that there is no need to check their conclusions against reality. This is abundantly clear from my comments.

If their conclusions are valid, I accept them and am happy to do so. If they are falsified by real world data, then I accept that too, but the Austrians don’t. It appears some Austrians consider that if theory and reality conflict then it must be reality that is wrong – if they did not think like this, then they would have to accept that such a conflict means their theory is wrong. Since they don’t do this, they must logically assume reality is wrong or can be ignored. This is utterly insane and probably goes a way to explaining why Austrian economics are seen as somewhat fringe. They are simply not grounded in the real world. Logical proof should be left to mathematics, not the real world.

As for polycentric law, I understand the theory but dispute the practicality. Essentially, such a system is a regression to petty fiefdoms. If it is done within a single fiefdom, then it is the cause of unnecessary confusion, duplication and waste. It causes enough problems in the UK with the distinct English and Scottish legal systems, and even they have been brought very close together (really Scottish (Romano-Dutch) law has been brought more into line with English common law).

I cannot see a practical advantage of having multiple different systems of law “competing” in a single society. Doubtless there are theoretical advantages, but the reality of a unified system is that nobody is in doubt as to what the law is – and it can of course be changed. Of course, polycentric law is a great idea if you’re a lawyer, but otherwise it seems a little silly, wasteful, expensive and ultimately futile as it would no doubt soon revert to a unified system unless someone compels otherwise, which is hardly libertarian.

Then what is it? What do YOU call it when someone takes something and asserts it as his own private property when previously it was not owned by anyone? That’s not a rhetorical question.

It is, but what does that have to do with the grant of a right of property where that property was not previously owned? If property not previously owned is declared with legal force to be the property of a specific entity, then that process is either right of conquest or a coercive interference.

EG

Euan, your clearly do not understand what underpins much libertarian or classical liberal thought, particularly why Austrian Economists think what they do. You have not got a clue, in fact.

Rather than waste interminable comments pointing out how it really works, might I suggest you read The Fabric of Reality by David Deutsch, which explain rather well and in non-philosopher-speak, why the inductive data approach you are so prone to is, well, a complete crock.

Perry,

I am not arguing against liberalism, but against the insanity of the Austrian method, as you well know. Where that same method is used in other areas of liberalism, it is equally daft.

It is the deductive logic approach to economics that is a crock, and even a cursory glance at the real world shows this to be true. Such a method is really pseudo-science – indeed pre-science – when applied to real-world things such as economies and human behaviour.

In many areas of Austrian thought, the theory is flatly contradicted by reality: the superiority of the the gold standard; the need for state interference to have monopoly/cartel arise; the causes and nature of the business cycle; the ability of the market to self-regulate, and so on and on. There are a great many books and articles available which tear the Austrian methodology and many of its conclusions to pieces, if you’d care to read them.

It will not do for Austrians to say that real world data is meaningless in assessing the validity of the theory. Hayek himself said explicitly that economic theory cannot be proved or disproved by reference to reality, and more egregiously went on to say that all that was necessary was to confirm that all the theoretical assumptions had been considered. Gaillot says the theory can only be falsified by falsifying its theoretical assumptions. I could go on. It is not me saying these things, it is Austrians themselves.

This means that where real world data contradicts the theory, it can be ignored. How sane is that as a principle for running an economy? The theory says it is correct, therefore it is correct.

If your theory makes a prediction, then there must be a means of falsifying it. This elementary principle is known to anyone who has had any exposure to the scientific method. If the theory is not falsifiable, it is not a theory. Period. The problem with Austrian economic thought is that it forbids the use of real world data to test the theory. How, then, would anyone be able to tell whether Austrian theory works or does not work in practice since nobody is allowed to use the one thing – real-world data – which could show it one way or the other? Pseudo-scientific rubbish.

I do have a clue, Perry. I understand how the scientific method works. I am familiar with many of the Austrian methods and conclusions, and they are absolutely not remotely scientific.

Most critically, I understand at both an abstract and a pragmatic level that if a theory says something but the real world shows this is not in fact the case then it is the theory that is wrong (or at best incomplete) and only a fool or a churl would say otherwise.

EG

I second what Perry said. By the way, Euan, your dismissal of polycentric law is unwarranted given that it partially exists in the United States, – go read the Federalist Papers – and of course patent laws differ widely around the world. It is not just a piece of ivory tower theory, which you seem to be implying. I actually think there is a lot to be said for encouraging “legal evolution” in areas as tricky as those like intellectual property. It is a mistake to dismiss it or try to find some sort of ideal from the off.

How property rights where none previously existed is an interesting question. Again, though, it hardly strikes me as intervention of the sort that is usually associated with that word, such as nationalisation or price control.

The assertion by you that the Austrian school of economics has no reference to the real world is bunk. Mises and Hayek for example both wrote a lot about the business cycle, a fairly real world issue, I would have thought.

But not within a single country. My objection is to having multiple parallel legal systems within the same geographical region.

I know, which is why I asked it, and presumably why I’m still waiting for a reply….?

But it is nevertheless intervention, is it not? I’m keen to read what you think it is if not.

I said it ignores real world data when that data contradicts the theory, not the same thing. Which it plainly does, by the admission of the Austrians themselves – so if you’re condemning me for saying this, you’re essentially condemning the Austrians.

An accurate but irrelevant observation, and if intentional then disingenuous. See paragraph above – the question is not real world issues, but real world data for validation of theoretical assumptions. However, since you brought it up:

Mainstream economic opinion is that the business cycle is an inherent part of the market economy and has nothing to do with state regulation or intervention. In fact, the record of history very clearly shows that the business cycle is more severe WITHOUT state intervention than with it. However, petty trivia such as what really happens in the world is not relevant to Austrian theory, so although history proves the Austrians wrong on this point, at the same time – from an Austrian point of view – it doesn’t because it is irrelevant.

EG

EG, like I said, laws on issues like bankrupty codes differ within some countries like the United States. (It is a funny feature of the US that companies shop around for the place to file for bankruptcy in). It may not be easy to imagine how this comes to pass when we live in a small country like Britain, but polycentrism should not be dismissed as you do.

I know that the business cycle is regarded within mainstream economics as part of the market and not caused by intervention. Thanks for that nugget of wisdom! I was not being disingenuous in raising the point. You have a habit of making bald assersions that the Austrians’ ideas were not influenced by real-world events and that they took no cognizance of them. Von Mises, for example, looked at economic history and what he felt about human nature to describe why socialist central planning would prove a disaster.

You claim that the Austrian school – quite a broad church – ignore real-world data. I’d like you to back up that astonishing assertion if you can. Prices, for example, are real-world data that these guys and gals write about constantly.

Johnathan,

You are missing my point, in both cases.

Polycentrism:

Even in America, there are not multiple parallel systems of law in the same jurisdiction. That is to say, you cannot choose between competing brands of federal law, or competing brands of state or county law within the same state or county. You might not like the law in Florida, and decide to move your business to Texas because that’s more suitable. But you can’t stay in Florida and pick a different set of Florida state laws to follow. That’s my point – within a single jurisdiction, you get one set of laws. This defines what a jurisdiction is.

In the US, the whole US is a single jurisdiction for the purposes of federal law. Each of the several states is a separate jurisdiction insofar as state law is concerned, but each is at the same time within the same federal jurisdiction. You can easily have a hierarchy of jurisdictions (going from county to state to federal, for example), but it is difficult, inconvenient, expensive and wasteful to have multiple different and competing systems at the same level within a single jurisdiction. What you essentially do then is split the jurisdiction (or nation, or state or whatever) into smaller ones, and so you have multiple competing (smaller) jurisdictions. All you achieve is to break up a country – you might take the US from 50 to 150 states within the same land area, but that’s about all you’d achieve. What’s the point of adding the cost and complexity?

Austrians say it is caused by state intervention. You, me and the vast majority of the world’s economists consider them wrong on this point, but STILL they will not consider the vast real world experience which shows very plainly that they are wrong. That’s my point.

NO, NO, NO! I’m NOT saying that. I’m saying Austrians deny that real world data is of any utility in validating or otherwise their ideas. They say this quite explicitly – I gave the examples above of Hayek and Gaillot, and of course many others all say the same thing. THIS IS NOT THE SAME AS saying that they did not come up with their ideas in response to real world issues.

I quite accept that the Austrians looked at the world and its issues & came up with their ideas as solutions to the problems they saw. This is, after all, what people tend to do. My objection to them – where I think they are swivel-eyed loonies – is where they say you cannot take real world experience to find out if they’re right or not.

If I say I am the clone of Napoleon, would you believe me? No. If I said you could use logic to prove me wrong, but I can use logic to rebut you, we might or might not get somewhere. But I have made an assertion that can be empirically tested by taking a DNA sample. If I say that’s meaningless and logic is all you need and all that will be acepted, you’re going to sneer a little, aren’t you?

So with the Austrians. They make assertions and predictions that can be empirically verified, but they deny the possibility of using empircal data to do the verification. Do you really not think that is just a little odd? An economic theory that refuses to allow itself to be tested? It’s right because we say it’s right? It doesn’t matter what the real world data is, the theory is correct because all the assumptions have been considered (Hayek) or the assumptions have not been logically falsified (Gaillot)?

Now, how about the question of the allocation of property rights where none existed before? Tricky, isn’t it? Do you think you’ll have to retract your profound disagreement that it is an intervention? Just wondering…

EG

Your writing efforts are heroic but you are not persuading me. Read again what I said about the US federal system of law. It has permitted a degree of evolutionary change, as the bankruptcy codes demonstrate.

I remain convinced that a “one-size-for-all” patent system is a bad idea and fresh thinking is needed on how to handle intellectual property rights.

I remain to be convinced that the “Austrian school” of economists pay no heed at all to certain facts in judging their theories as you claim. As most the major figures argued, the market order is the ultimate feedback system.

It is true, mind, that there are weaknesses in my view in the Austrian school (I am not a blanket defender of them). However, the drawbacks are heavily outweighed by the plusses.

Yes, laws change over time. This happens in every democracy, does it not?

But there are not multiple competing federal codes of law in the US, are there?

Where laws differ from state to state, this is because the subject of the law is reserved in whole or in part as a state and not a federal responsibility. It’s hardly polycentrism, and it’s hardly unique to the US. The same principle even applies in the UK where there are distinct differences between Scots and English law. Indeed, the principle applies to a lesser extent to local government bye-laws, which vary from county to county in the UK.

I agree. I just don’t think a pointlessly complex and expensive system of multiple “competing” legal systems is the way to do this.

Read Hayek and Galliot. They said it. Rothbard has said the same thing. I’m not inventing this stuff, it is straight from the Austrians themselves.

Now, how about our grant of property rights question?

EG

Well we’ll have to disagree about the Austrian thing. I guess it depends on what you mean by “real-world facts”. I haven’t really the time to debate that further now.

Granting of property rights: a major one. I tend to take the view that some property rights, such as to physical goods, land, and other “tangibles”, have their origins so far back that it is hard to know who or what “granted” them or whether they emerged from a sort of pre-legal order.

With granting of things like patents by a government patent office, it appears in many ways to be an arbitrary process, but to be fair I don’t see how one easily solves that. Consider: should the patent last for a year, 10 years, 100 years? How much should a patent register cost? Who decides what counts as a patentable invention? Can other would-be inventors challenge it?

It seems that one of the hardest nuts to crack for property rights theory is IP, precisely because, as modern software business shows, the boundaries of what is mine or thine