The following stands out among the many comments to my previous post on Iraq.

How much is an Iraqi life worth? To me personally, about zero. Here’s why:

– I have no friends in Iraq (and doubt I ever will by the end of this post)

– No Iraqi signs my paycheck

– No Iraqi makes anything special that I can’t buy anywhere else (oil?)

– Iraq is on the other side of the globe“But they’re being killed” you say. So are many other people. What about the North Koreans? What about the people who will effectively be killed because they cannot afford medical care due to this war? What about third world countries where parents have more children than they can afford to feed? Please make an objective, logical argument why the life of an Iraqi rates above (not just equal to) these others.

There are two issues in this comment. One is the old boring question “Why Iraqis and not North Koreans, or Chinese, or any other suffering people?” We have repeated countless times here on Samizdata.net that we do not consider lives of Iraqis above other individuals suffering elsewhere. Yes, I do want the world to be rid of North Korean, Chinese, Iranian and any other statist murderers. By yesterday, if you please. It’s long overdue and given that my taxes also pay for the army (or what’s left of it), I have no hesitation in supporting its use in cases when this becomes part of a government strategy.

The fact that the US and UK government policies are temporarily aligned with my view of the world does not redeem them in my eyes or make them somehow better entities. My objections to the state and my hatred of anything statist is not negated by my support of Bush and Blair in their determination to give Saddam his due. Samizdata’s eye will watch over the American attempts to establish democracy in Iraq with the same vigilance as ever and hurry to point out any misdemeanour by the inherently collectivist and kleptocratic state.

More importantly, the comment touches on an issue far greater than Iraq and the international pandemonium associated with it. Why do most of us hate to see people suffer? Why should we be moved by a sight of a child corpse, a woman tortured or a man shot? Why does the world remain shocked, moved and outraged by the suffering endured by those in Nazi concentration camps and Stalinist gulags (although unfortunately too few pictures serve to fuel the horror over those)?

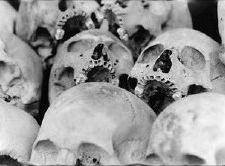

I do not count myself among the emotionally incontinent (public expressions of grief) and the emotionally unsatiated (reality TV). My outrage comes from the belief that an individual is more important than a lofty idealistic concept, more so since every ‘utopia’ has built its edifice on a large pile of human bodies. The more idealistic and utopian the vision, the longer it takes to defeat it and the larger the ‘mountain of skulls’ left behind.

Savonarola’s Florence, Robespierre’s France, Stalin’s Russia, Hitler’s Germany, Mao’s China, Pol Pot’s Cambodia, Kim Jong-il’s North Korea, Saddam’s Iraq, note that there is an individual’s name attached to every totalitarian nightmare. We are forced to ‘care’ about them, whether we like it or not. If we are lucky, we have not been affected directly, but they certainly had an impact on the way we live today, simply as a result of the international politics shaped by their existence. We see people suffer on TV everyday. They suffer even more off screen. Should we mobilise the world every time this happens until there is no more pain? Sounds like utopia to me. However, there is a difference between suffering caused by natural disasters and pain inflicted on an individual by another. The first inspires compassion and assistance, the second moral outrage and a corresponding action to remove the oppression.

“But why should I care about someone else being oppressed when I am busy building my life to my specifications and according to my abilities?” I hear you say. You attach certain importance to yourself, which is natural and right. An individual Iraqi, North Korean, Chinese would feel the same, if not for some homicidal megalomaniac ruling his country. Self-awareness is the most fundamental expression of a human being as an individual and one of the greatest sources of evil is the ability of one human being to deny this to another.

Again, why should ‘we’, individuals living in another country, ‘other side of the globe’, do anything about it? The first part of the comment reads to me exactly as this (in)famous quote:

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing…[and elsewhere]…My answer to those who say that we should have told Germany weeks ago that, if her army crossed the border of Czechoslovakia, we should be at war with her. We had no treaty obligations and no legal obligations to Czechoslovakia and if we had said that, we feel that we should have received no support from the people of this country…

These words were uttered by Neville Chamberlain before one of the most appalling episodes in modern European history. His ‘sensible’ attitude did f**k-all to prevent or restrain what followed. These words were said after:

The rights of humanitarian intervention on behalf of the rights of man, trampled upon by a state in a manner shocking the sense of mankind, has long been considered to form part of the recognized law of nations. If murder, rapine, and robbery are indictable under the ordinary municipal laws of our countries, shall those who differ from the common criminal only by the extent and systematic nature of their offenses escape accusation?

These crimes [crimes against humanity] were committed both before and after Nazi Germany had launched her series of aggressions. They were committed within Germany and in foreign countries as well. Although separated in time and space, these crimes had, of course, an inter-relationship which resulted from their having a common source in Nazi ideology; for we shall show that within Germany the conspirators had made hatred and destruction of the Jews an official philosophy and a public duty, that they had preached the concept of the master race with its corollary of slavery for others, that they had denied and destroyed the dignity and the rights of the individual human being. They had organized force, brutality, and terror into instruments of political power and had made them commonplaces of daily existence. We propose to prove that they had placed the concentration camp and a vast apparatus of force behind their racial and political myths, their laws and polices.

As every German Cabinet minister or high official knew, behind the laws and decrees in the Reichsgesetzblatt was not the agreement of the people or their representatives but the terror of the concentration camps and the police state. The conspirators had preached that war was a noble activity and that force was the appropriate means of resolving international differences; and having mobilized all aspects of German life for war, they plunged Germany and the world into war.

We say this system of hatred, savagery, and denial of individual rights, which the conspirators erected into a philosophy of government within Germany or into what we may call the Nazi constitution, followed the Nazi armies as they swept over Europe. For the Jews of the occupied countries suffered the same fate as the Jews of Germany, and foreign laborers became the serfs of the “master race,” and they were deported and enslaved by the million. Many of the deported and enslaved laborers joined the victims of the concentration camps, where they were literally worked to death in the course of the Nazi program of extermination through work. We propose to show that this Nazi combination of the assembly line, the torture chamber, and the executioner’s rack in a single institution has a horrible repugnance to the twentieth century mind.

You might have guessed that these are extracts from the prosecuting speeches at Nuremberg Trials. (The first paragraph was from one made by Sir Hartley Shawcross, Chief Prosecutor for the United Kingdom. The rest is from the speech of Mr. Thomas J. Dodd, Executive Trial Counsel for the United States.) I resorted to this historical example of tyranny, oppression, human misery caused by the Nazi state, ideology, bureaucracy and most of all individual Nazis, because it is recent, well documented and its horrors rarely denied. The consensus is that defeat of Germany had been necessary not only for strategic and military reasons but also from a human standpoint. The aftermath may have spawned international laws and institutions that deserve severe criticism in their present form. Nevertheless I would argue that the moral force of their underlying principles remains unabated.

It is an impossible and ungrateful task to try provide irrefutable grounds to those who do not already believe in the intrinsic need to defend individual freedom whenever it is seriously threatened. To insist on such a moral imperative for everyone would be foolish. Instead I insist on consistency. If you believe that it was important to fight the likes of Nazi Germany and its ideology not only as self-defense measure, then extend that reasoning to Iraq, North Korea, China, Iran. To argue that the US, UK and other governments are not worthy to be moved by such considerations and that their actions are driven by non-humanitarian, self-interested or utilitarian objectives is a non-starter. The countries fighting in the WWII were far from perfect. The Allied armies were commanded by the same kind of statists as the ones that live off our taxes and erode our civil liberties. Indeed, after the war, they all got back to doing so with greater vigor. But that is the stuff of daily posts on Samizdata.net.

If freedom of individual matters sufficiently to oppose the US and UK state, it matters more in Iraq and anywhere where such expression is suppressed and our ‘libertarian’ truths ring hollow, if we deny them to anyone but ourselves.

>Samizdata’s eye will watch over the American attempts to establish democracy in Iraq with the same vigilance as ever and hurry to point out any misdemeanour by the inherently collectivist and kleptocratic state.

The early omens are not auspicious:

Hear, hear! (or is it ‘here, here!’?)

[to the samiz. article]

That comment was not a response to your post, but to this one by Perry de Havilland. And I noticed you snipped quite a bit of the original comment, including this:

This could apply just as easily to any of the Crusaders. You’ve made it perfectly clear that you’re in favor of stealing money from me at gunpoint (and shooting me if I resist) just so you can pay other people to go do your killing for you.

Yes, that’s “old style morality” all right. Downright conservative, in fact.

>Samizdata’s eye will watch over the American attempts to establish democracy in Iraq with the same vigilance as ever and hurry to point out any misdemeanour by the inherently collectivist and kleptocratic state.

Good. We’ll hold you to that.

“We are forced to ‘care’ about them, whether we like it or not.”

It’s not so much whether we like it or not. It’s whether we know about it or not, or — more to the point — whether we see, or can imagine seeing, barbarous visual images on our TV screens.

The West basically doesn’t care about the Sudan (to give one example) because Big Media doesn’t force us to look at it and think about it.

However, there is the question of whether we should, morally, care about people suffering. The mainstream view is that we should. George Perry (above) seems to imply that the only reason we should care about people’s suffering is that it affects us through, basically, looking bad on our TV screens. I don’t think that systems of morality can be externally justified, but the mainstream system of morality for libertarians and others is utilitarianism, in which suffering is bad, and which therefore says we should try to stop suffering.

Perhaps I have misinterpreted George; perhaps he was merely saying that there are other people who are suffering more but we do not see and therefore we should deal with them first. I sort of agree with that; someone online said that the Palestinians only get our attention because they kill people, not because their claims are the most justified of ethnic minorities in the world.

Yes, Malex; you have “misinterpreted” me, as you suggest. But not quite — I’m not encouraging us to find out who’s suffering most, and “deal with them first”. No, what I believe is that people suffer everywhere. Some suffer very much indeed. For some of these suffering people, we send in the “cavalry”, which seems a very moral thing to do. And yet, this very “rescue” too often perpetuates the suffering, which may then be transmogrified to a different and more palatable (for the West) form.

A people need to bring about their own “rescue”. When tyrants are disposed because the subjects of the tyranny revolt — this is the best hope for a lasting, liberal outcome.

Ok, so you are agreeing with the objective but not the method. Reasonable people can disagree about whether Western intervention is actually effective in allaying human suffering.

Ken Hagler/Michael: Sorry for the confusion of comments, I could have sworn it was one of mine – one can get lost in the comments, especially over the last few days.

Also, Perry has replied elsewhere to the point you thought I ‘snipped’. Since you were addressing it to him, I did not find it appropriate to respond. For myself, I have made my own personal sacrifices when it comes to the defense of this country. And yes, it has to do with the military… But I don’t see what that has to do with my beliefs.

Could you please point us to the place where we make it “perfectly clear that you’re in favor of stealing money from me at gunpoint (and shooting me if I resist) just so you can pay other people to go do your killing for you”…? You must be confusing us with some other blog, in the heat of the argument. 🙂

How do I condone any of the above by pointing out the horrors of collectivism, totalitarianism and the need to resist them even if they do not affect us directly?

T.J.Madison: And how exactly do you propose to hold us to that?!

Caring about people who suffer is one thing. Taking this or that action to alleviate their suffering is a different thing. Some times it should be done. Some times it cannot be done. Some times (as I suggested earlier) it perhaps should not be done.

Finally, George: The quote “We are forced to ‘care’ about them, whether we like it or not.” refers to the oppressors who by their actions affect the world beyond their immediate sphere. Look again at the list of tyrants I chose to mention and every one of them shaped the world beyond their place and time. Their actions affect us, whether we like it or not and so making it impossible or difficult for individuals like that to fulfill their totalitarian visions must be a good thing.

Malex: I deplore utilitarianism and don’t care much for ‘mainstream system of morality’ for libertarianism or any other -isms. BTW, where did you get the utilitarianism/libertarianism connection?

My 2p to the discussion, ones I’m sure Perry would agree with. There are very few cases where we need to actually act militarily. In many of the other “problem” countries, even if they are today doing bad things, they are doing less of them than yesterday. Few would doubt Russia, China and Iran are much improved over their state in 1980, and all appear (to me at least) to be trending towards more liberal societies. Each is at a different place in it’s journey, but each is indeed *on* the journey.

Some nations, like Iraq and North Korean, are basically lost causes. The people have no hope of slow change or overthrow without external assistance. In the case of Iraq, Saddam’s son’s are even worse than he is, if such a thing is possible. There is every sign of a dynasty which would, in the normal course of events, last for several generations. Iraq’s economy is run more like that of Nazi German. If the Baath Party are socialists, they are of the National variety. Thus the economic power of the country is enough to keep things turning over. They might not run well, but they do run well enough.

North Korea is in someways more dangerous, but also likely to collapse on its’ own. It also has nowhere to go with its huge military. They are easily containable. Iraq is *not*. It’s surrounded by porous borders and smugglers routes dating to the dawn of humanity. What Saddam wants in or out, he can get in or out with at least the effectiveness with which heroin gets into the USA.

I’ve followed with great interest the captures of small amounts of fissionables being smuggled through Turkey. I take them as indicative of far larger amounts which got through. Consider how well Turkey has done historically at stopping the heroin trade.

‘The quote “We are forced to ‘care’ about them, whether we like it or not.” refers to the oppressors who by their actions affect the world beyond their immediate sphere.’

Gabriel, I’ve lost the thread, I’m afraid. But I’ll try to explain myself in the terms you use:

Being “forced” to care about those who suffer is a Western affectation which, I believe, results from the sentimentality “we” feel when confronted with images of the suffering. The “forced” part derives from “our” slavery to the telly, et al: “we” almost almost literally cannot turn off the tube and, instead, read Henry James.

As for the “oppressors…who affect the world”, there are relatively few oppressors who “affect the world” in our time. They affect their own people, sometimes gravely. And they may affect their neighbors. But very few affect the world. Isn’t that what “Iraq” is all about right now? This Saddam may be a first rate son-of-a-bitch, but he doesn’t “affect the world” (one view). Or he damned well does (the opposing view).

George Peery: As for the “oppressors…who affect the world”, there are relatively few oppressors who “affect the world” in our time. They affect their own people, sometimes gravely. And they may affect their neighbors. But very few affect the world.

And how much of the 20th century was not affected by the Nazis and Communists? Remember two world wars and the cold war? Would you say those affected ‘relatively few’? Every time I take the subway and there is another terrorism alert or some scare (often), I am affected.

Perry de Havilland, your comment is not entirely coherent. But let me just say that the first duty of thoughtful people (or one of them) is to make intelligent distinctions.

The first half of the 20th century did not affect “relatively few.” Agreed. But so what? Now we are in the first half of the next century.

I’m sorry that you are anxious on the subway.

(1) a/b utilitarianism –

It *is* generally accepted in society at large, not that this fact is a good argument for it’s truth.

Some libertarians use it in their arguments for libertarianism (ex. Mill, On Liberty (title not sure))

Other libertarians don’t like it very much (ex. Ayn Rand) but I haven’t found a justification of libertarianism under other moral grounds that I like very much.

Plus, one should not choose one’s moral system based on the political conclusions it drives one to 🙂

I just think that utilitarianism sounds good (even though it doesn’t really tell you what the “good” [in “greatest good for the greatest number”] entails).

Yeah, give me something better (although I think moral systems are all logically equivelant, and I’ll take it. Until then, it’s useful to assume libertarianism because that’s what most opponents accept.

Oh, I forgot; rights theory is also mainstream. That’s good stuff too. Maybe you’re a rights theorist.

this is going to be a lot of comments, but I want to note that rights theory and utilitarianism come to about the same conclusion in this case.

ok,

working backwards:

a) George Peery: I think Perry de Havilland was being ironic; they obviously did not affect “relatively few.” And the objective of the subway example is to say that things that happen far away (ie the Middle East)

b) Perry de Havilland – Peery may mean “now” by “in our time” in which case Hitler etc. do not count.

c) George Peery –

you said:

Being “forced” to care about those who suffer is a Western affectation which, I believe, results from the sentimentality “we” feel when confronted with images of the suffering. The “forced” part derives from “our” slavery to the telly, et al: “we” almost almost literally cannot turn off the tube and, instead, read Henry James.

I thought we concluded that helping oppressed people was a worthy aim but perhaps (your view) almost never worth the cost. Not that we only want to help them because the telly forces us to, but that we should help them but it would be bad on balance.

“I thought we concluded that helping oppressed people was a worthy aim but perhaps (your view) almost never worth the cost. Not that we only want to help them because the telly forces us to, but that we should help them but it would be bad on balance.”

Malex, you are honing in on my point of view (although I somehow missed whatever it was that “we concluded”).

Some old boy (I can’t recall exactly) said that a people have the government they deserve. Something like that. I would, hopefully, flip that observation over and suggest that, when a people do not have the government they deserve, they should take it upon themselves to change that government.

The liberal West can take on that task, but it really isn’t the same as the opposed people taking it on themselves (cf 1980s Poland).

You accuse me of believing that coming to the aid of the suffering is “almost never worth the cost”. Close, but not quite. The nation-state that is possibly in a position to relieve the suffering may have national interests that coincide with actions that provide that relief. Many people of our time would consider that view to be cynical, but I am of an earlier time. I spent two years fighting Communists in Vietnam. This did, I hoped, relieve some of the suffering of the South Vietnamiese; it also (I hoped) sent a message to international Communism that we, the West, would not sit idly by while they trampled over innocent people. Well, the good intentions there did not work out in the short run, though arguably they contributed to victory (the Cold War) in the long run. In sum, a state’s national interests may coincide with rescue of the suffering.

There is one other comment I’d make, one that’s perhaps pertinent: I don’t think of suffering as something thoroughly bad — somthing to be avoided at all cost. For example, I believe that the suffering incurred by a wife/husband while caring for her or his spouse is, morally, a very good thing (though not at all enjoyable). That puts me very much at odds with Western sensibility today.

George –

Ok, your position is rather complicated.

On the one hand, you say that national self-interest sometimes coincides with relief of suffering. Then, nations should relieve suffering, and you seem to see this as a good thing. However, you do not think nations should interfere when their self-interest is not involved.

This combination of beliefs leads me to say that you believe the relief of suffering is good, but not worth any extra effort. You say that sometimes it’s not bad, but that doesn’t seem to apply in this case. It is not the victims’ fault that they suffer under dictators.

Continuing with that point, they do not deserve to suffer just because they have not overthrown their dictator. Morality is an individual thing. Each individual does not have an obligation to work to overthrow an oppressive govt. at great cost to themselves (although it is a good thing to do). Therefore, a people as a whole cannot be held to this standard.

oh, and about “concluding” earlier, we had a little discussion above about “sending in the cavalry” which you seemed to see as morally motivated but ultimately ineffective. Which led me to say that you believed we should relieve suffering but we cannot.

Hmm, Malex, you seem to be making much ado about very little.

The (mostly) emasculated West cannot solve every political problem nor relieve every instance of suffering. If this is not true, please explain why it is not.

It hasn’t been *my* wish, over recent years, that Western countries become so militarily weak that they cannot even unscrew things in the Ivory Coast (to give a recent example). But that’s how it is. My own country (the USA) has done better in this respect. (I don’t mean to boast.) But even the US cannot confront all the world’s evil — actually, many in the West seen to think the US itself is “evil”.

Well, this “very little” includes the war in Iraq, which many assign great importance to :-).

It is true that the West cannot solve every problem in developing countries. It is also true that this fact does not prove that the West should not solve the problems that it can. The US is capable of overthrowing the Iraqi government. Whether it is capable of instituting a popular democratic regime without hugely bad consequences is another story. The attitude of much of the world towards the West (esp. US) has to do with the second question, not whether the West is capable.

I’ve readall this carefully, and I don’t get Peery’s position; or if I do, it’s pretty mixed up. We have to dstinguish between the political and moral spheres.

Of course, as moral beings, or just human beings, we should fight oppression and inhumanity wherever we see it. To think otherwise is at best amoral.

Of course what is politically impossible will not be attempted by any government or leader with a self-preservation instinct, hence he toing and froing in Europe at present; and what is practically possible has its limits too.

But we must tackle the worst and most dangerous cases regardless of political risks –– our survival as civilised societies is more important.

Vietnam is an inappropriate example: in the end, for political expediency, the South Vietnamese were abandoned to their fate, a pretty dire one for those actively involved in the war effort.

Dave Farrell: Thank you for the distinction between the moral and political spheres. It appears that George Peery has not read the article at all! It is indeed about the moral position and not the political here and now.

His statement that tyranny and dictatorships do not affect the ‘larger’ world is ridiculous. The whole theory and practice of international relations and the international politics revolves around attempts to prevent such things. Botched, you might say, but still there. The United Nations was created for the same reasons, marking the return of natural rights the international law and politics – the notions that were used to convinct the Nazis, reaching beyond the dubious legality of their state. NATO owes its birth to the West’s reaction to another dictator, Stalin, and the Cold War. The same institutions are making headlines today and define the actions we are taking yet, against another dictator. Hm, not much influence then, Mr Peery…