If you’re not a Doctor Who fan it is probably best to look no further.

Well, don’t say you weren’t warned.

I won’t bore you with the details of when and where I watched my first episode of Doctor Who, suffice to say that the Doctor was played by Jon Pertwee and that I was immediately hooked. But I was in for a surprise. In the serial The Three Doctors, Jon Pertwee once again played the Doctor. And so did Patrick Troughton. And so did William Hartnell. This was all rather baffling until it was explained to me that as they had played the Doctor in the past, these two apparent imposters were in fact every bit as genuine as Jon Pertwee’s real thing. Which raised an intriguing possibility: other episodes. Other episodes that I might one day watch. Other episodes that I might one day watch because the BBC with the unique way it was funded, free from the need to make a profit, would be looking after them for me.

Except it wasn’t. Something like two fifths of the Doctor Who episodes produced before 1970 are “missing” from the BBC archive. Although it is now 20 years since I found out about it, I still find it difficult to believe that such an act of cultural vandalism was allowed to take place. But it was.

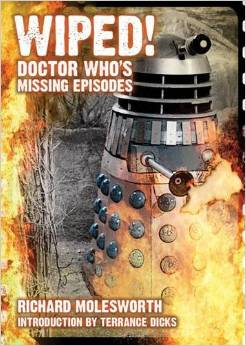

So why are so many missing? In Wiped! Richard Molesworth describes the whole sorry tale in exhaustive (and some times exhausting) detail. It begins with Doctor Whos being recorded on videotape. In the 1960s videotape was a new technology and as such, expensive. Broadcasters were understandably keen to re-use the tapes whenever they could.

Another factor in this was the deal that the BBC had made with the actors’ union Equity. Younger readers may be unfamiliar with this but in the 1960s and 1970s unions were extraordinarily powerful. The deal between Equity and the BBC meant that an episode could only be repeated for two years and after that only with Equity’s specific permission. So, you’d have a situation where after 2 years you would have videotapes that effectively could not be broadcast and an engineering department banging on the door demanding they be allowed to wipe them. As a consequence every single inch of 1960s Doctor Who was wiped. It was far from alone. Episodes of Top of the Pops, the Likely Lads, Not only but also…, Z-Cars, Til death us do part and many others met a similar fate.

In the interests of fairness I should point out that when it came to wiping TV programmes the BBC was far from the only offender. There is almost nothing left of the first season of the Avengers for instance. Or Sexton Blake. About half of the highly-rated Callan (played by Edward Woodward) is also missing. However, all the Saints and Danger Mans are still with us. Meanwhile, my understanding is that most American TV, even from the 1950s still exists.

But that is not the end of the story. Britain was not the only market for Doctor Who. Episodes were sold throughout the former British Empire and, oddly enough, Ethiopia. To do this the videotapes were used to create films in a process known as “tele-recording”. The telerecordings were sent to the customers with strict instructions that after they were used they must either be returned to the BBC or destroyed. Why destroyed? who knows, but those were the rules.

Every episode of Doctor Who in the 1960s was recorded in black and white. By the early 1970s the BBC was broadcasting almost exclusively in colour. Most of the world was also going over to colour and sales of the black and white episodes started to dry up. Reels of film would show up at the BBC with almost no obvious commercial use – the home video market was still many years away in the mid-1970s. Short of space, the department responsible, BBC Enterprises, had three options. They could give the films to the BBC Film Library, to the National Film Archive or they could throw them on the skip. Although Molseworth does not state this explicitly, it would appear that private ownership of BBC copyright material was (and is for all I know) illegal, and so selling these films to the general public was not an option. In most cases the BBC chose to file the episodes in a skip.

One thing that particularly sticks in my craw is the fact that even after the BBC did everything in its power to destroy these episodes it still has copyright to them. This has some very peculiar effects as I shall explain.

As I said, many episodes no longer exist as films or tapes. But all the audios exist (recorded off-air by fans), as do the scripts and a large number of photographs, otherwise known as “tele-snaps”. Over the years a cottage industry has grown up assembling these disparate elements into what are known as “reconstructions”. Now, they’re not very good and they are really only for the dedicated fan – people like me in other words – but right now they are the best we’ve got. Sadly, these too are affected by BBC copyright. For many years they were only available on videotape and on a non-profit basis. The producers were wary of annoying the BBC. And then one day someone (quite reasonably you’d think) decided to start putting them up on YouTube. Oh dear, the BBC really didn’t like that. Not only did they force YouTube to take a whole load of them down but seem to have closed down the reconstruction business temporarily if not permanently. Bastards.

And there are still people who keep claiming copyright and such deserves as much protection as any other “property” despite being just a state-sanctioned monopoly.

FD

And they carried out exactly the same sort of cultural vandalism with their music archive.

They had a music archive?

Why does the state involve itself in the light entertainment industry at all?

Have you seen the formerly missing episodes from the Patrick Troughton era? The ones that were found in Africa, (Kenya, if I remember correctly) a couple of years ago?

There were segments that were animation rather than the original scenes, but in spite of that, they made for enjoyable viewing. It would be great if more missing episodes turned up somewhere.

Meanwhile, my understanding is that most American TV, even from the 1950s still exists.

For recorded prime time TV, this is probbaly true. For live and daytime TV, I’m not so sure. In the US with our four time zones, it wasn’t uncommon for kinescopes to be made to get episodes out to the west coast so that people there could watch the episodes at the same local time as on the east coast. Also, with local broadcasting stations needing programming, syndication was common which gave the content makers a reason to hold on to the programming.

At least, this was the case when there was pre-recorded material and an easy way to monetize it. Daytime programming like soap operas and game shows would have been considered difficult to reuse, so those tapes were wiped into the mid-1970s. Also, most of the Tonight Show episodes Johnny Carson made before the move to Los Angeles in 1972 are considered lost. You may enjoy reading The day my grandfather Groucho and I saved “You Bet Your Life”.

NB: I should probably have put that whole link in quotes. Groucho Marx wasn’t my grandfather, of course, but the grandfather of the article’s author.

@rae9582 Yup. Downloaded them within 24 hours of them becoming available. The episodes discovered – from Enemy of the World and Web of Fear – were originals. The BBC has animated a few episodes e.g. Moonbase, The Ice Warriors for DVD release. As you say they’re quite fun even if they’re not the “real” thing.

It is all very odd. Apparently the last best hope for some of the episodes is Zimbabwe! Some of the reconstructed (from audio and story-boards) episodes are rather well done, mind.

I worry that I may have been dismissing the efforts of the “reconstructors”. What they have managed to do is to get as close as we are going to get short of an animation or the real thing. Some of the techniques they’ve used in terms of animation and cleaning up of images is hugely impressive and I am hugely grateful to them. I was merely making the point that the end product can be a bit of a struggle to watch.

One also wonders what might have been achieved if the BBC had been relieved of its copyright and these people had been free to make a profit.

Frederick Davies:

Clearly, the BBC’s ownership of the episodes was not recognized in law, because they were not allowed to sell them. That is the root of this particular problem.

A question so obvious it escapes millions. The answer I suspect is because it can.

I was actually thinking about the ‘missing’ episodes the other day, even though I have no TV and do not fund the BBC. I was thinking along the lines that for the bureaucrats of the BBC, any ownership of future rights (and future income) was hardly important to them as they had their funding from a licence fee requirement which effectively relieved them of the responsibility of running their affairs economically, a dreadful state of affairs for any human being, as we can see from Havana to Havant. The BBC managers had no reason to think beyond their next instalment of State funding, and of course, keeping the actors union (what an absurd strike that would be) sweet (a Union that has deprived its members of a potential lifetime of repeat fees) was a luxury that a commercial broadcaster might have had more reason to play hardball with, although the history of the UK’s print unions, who were able to stop any newspaper at will until Mr Murdoch broke their stranglehold over the major titles with his move to Wapping, shows that many private employers in those days were as much in thrall to Unions as the State.

Regardless of the rights and wrongs of copyright (for the record, I’m against), the BBC, as a “public” corporation shouldn’t own any copyrights at all.

If the corporation belongs to “the people” then all the copyrights should belong to “the people” as well- I.e. any British Subject should be able to copy or distribute any BBC production, and should be able to obtain any recording from the BBC archives by providing a blank DVD or VHS and a stamped addressed envelope, like we used to do with public domain software back in the dark ages.

Otherwise, it’s not a “public” broadcaster at all, it is a private corporation funded by state-sanctioned extortion.

I am for copyright as long as it lasts no more than 30 years past creation (not artist’s death)

And the 30 years is 15 automatic with another 15 if you file the forms and renew.

Copyright is mostly evil because it has become perpetual.

It is all horribly true Patrick.

The answer, of course, lies with technology.

Those transmissions *are* out there, available for capture, if you can contact the locals in the vicinity of Capella in the next few months, they should be able to get screeners of anything from after 1967 onto Laserdisk for you.

I recall an article in, I think, “American Cinematographer” that told the story of the recovery of a “lost” “Doctor Who” episode.

Someone found the surviving 2 inch “Quad” format tapes in Britain. The interesting part was that the series had been shot on FILM, in COLOUR and then transferred to tape.

However, at the time, many countries broadcast material straight from film using a scanner, a Rank “Cin-Tel” for example. Nordmende and another German company also made these “flying-spot” scanners for everything from 70mm down to Super-8.

MUCH superior image transfer compared to pointing a camera at a projected image on a screen!

Anyway, back to the original story. The tech types in the South African caper discovered that there were bits “missing” or “damaged” in both the film and tape versions of the show.

So, they transferred the film to tape, then dropped in the missing parts from the 2″ tape. The final trick was to use the early “colourization” technology to “colour-in” the monochrome parts, using the colours on the film as a guide.

“Colourizing” was, at the time, generally regarded as a “bastard” technology to sell old shows and movies to a new, “monochrome-illiterate” audience. Mostly the results were horrible. Material shot in “black and white” is lit quite differently from that shot in colour. A standard “process” was to wind back the contrast a LOT and then “colourize”. Thus, and dramatic “tension” provided by “juxtaposing light and dark, to enhance the dramatic moment”, went right out the window.

Furthermore, if you were dealing with a third or fourth generation tape copy, the “noise” and contrast “buildup” made things pretty ugly, especially in the days before the massively powerful DSP “engines” found in modern digital video-editing “work-stations”.

I believe in copyrights and patents, because they do encourage creation and progress. Tha’s their whole rationale.

AND, I believe that copyright and patent owners have a duty to make their creations commercially available.

If the bbc asserts ownership, then the bbc ought to make the things available. If they don’t for a reasonable period, the copyright ought to be considered abandoned.

And in this case, I believe the bbc’s destruction of the only extant films WAS abandonment.

Plus, really? Griping about homemade Doctor Who clips? What halfwit made that decision?

So an ordinary organisation may have recognised the value in resale of these items, the BBC not having a profit motive saw fit to scrub the tapes.

I know a lot of old films met the same fate in private hands, but at least they had the excuse of it being highly inflammable.

Not quite, it wasn’t the lack of a profit motive, it was, IMHO the absence of economic pressure to make a return, money coming in regardless through the State-backed licence fee, which is not the same thing. These days the BBC has a commercial arm to sell its wares, both to other broadcasters and to the public, the latter having been effectively unreachable in those days due to lack of domestic video technology, only printed material being merchandisable.

Copyright also got in the way, as did myopic Union pressure.

People have a lot of nerve, making something and selling or even giving samples of it to the general public, and then deciding one day not to sell it or give it away anymore.

People loved it and got used to having it there, and then it — wasn’t there! The NERVE!!

There ought to be a law.

. . .

I sympathize with the Dr. Who fans. You can’t imagine how much I sympathize! Back in the pre-VCR days, it broke my heart that the wonderful old movies like Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Fantasia, the classic Westerns, the dark dramas like Key Largo, the great musicals … all were gone.

Thank the Great Frog that technology and business self-interest showed their beautiful heads and we can now see so many of the Golden Oldies again. (Including, I discovered while foraging on UT, a B-&-W comedy I loved as a pre-teen: Private Secretary, starring Ann Sothern. Who also, by the way, played the femme fatale in the movie The Man Who Came to Dinner. Bette Davis was the female lead. I always thought that that casting was exactly backwards.)

But … nobody except its maker has a right to Product X. If Jack Jones, who used to make X (not as employee nor under contract), decides not to share it any more, or not to make it, or to tear it up and put it in Polly’s cage … it’s disappointing and frustrating as the dickens, but it’s his right to do as he will with his property.

Current copyright law may be poorly written, but the fact is that if someone creates X then X is his to do with as he will. One way or another, the custom will develop that in cases where X is released for use by the public (which always means the several individuals constituting it), the release will be either in the form of a license limiting the purchaser’s (or renter’s) use of the product, or in the form which gives the purchaser (there can be no renter) complete rights of use.

Regardless of how it came about historically, morally copyright law is entirely proper and appropriate (if well-written, though it will never be perfect), because it enforces the natural right of the producer to what he has produced.

I seem to have lost a paragraph in the foregoing, which is in defense of copyright law and specifically NOT a defense of the BBC’s handling of its Dr. Who series. In the first place, I don’t believe in public funding of TV, radio, any form of art, yadayadayada — we’re all supposedly libertarians here. The only hard case really is Public Health and to some extent scientific R&D, onaccounta defense.

And I don’t know what part the BBC played. Did it commission the series? Buy it outright? What? I have no idea.

No defence of the BBC (nor accusation either, except for existing at all) intended.

What Julie said. Staghounds, encouraging creation and progress, as wonderful as they are, are not the rationale, they are no more than welcome “side effects”. The rationale is upholding property rights.

Alisa,

Would you regard intellectual property rights as being similar in nature to physical property rights?

All of your happy are belong to us.

Julie, the big question in the case of the BBC is “who is the creator?” A quite reasonable argument can be made that it is the people who pay the license fee. I’m quite sure they are not extended any power in BBC IP decisions. As a government entity, the BBC is not entitled to the rights of a privately funded entity.

Alisa, in the US Constitution the power to create and enforce intellectual property rights is specifically “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;” I think that is what Staghounds may be referring to.

I’m in the camp that approves of intellectual property rights as derivative of the rights of life, liberty and property via this provenance. I have a right to my own thoughts. I have the right to keep them secret. I have the right to only disclose them to others on my own terms. Conversely, I have a right to consent to terms in order to receive the benefits (music, technology, whatever) of somebody else’s thoughts.

But, being accountable for damages caused by the accidental release of IP in my possession (lost ability of the creator to contract with others) is a terrifying thought. Probably one that would cause me to forgo the benefits of their thoughts.

The only truly natural rights/law are the law of the lion and the zebra. What rights we have are not natural, they are extended voluntarily by humans who associate on reciprocal terms to avoid carnage. The key purpose of these associations (various forms of society) is to negotiate the boundaries between individuals. I choose to honor the IP of others voluntarily much as I choose to honor their physical presence by not assaulting them. It is something I do as much for my benefit as theirs.

Which brings us full circle back to the phrasing in the US Constitution: “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;” I consent to these terms because I recognize intellectual individuality and the right to our own thoughts, but would also like to benefit from the open and profitable exchange of thoughts.

On a Constitutional law note, intellectual property should be “…for limited Times to Authors and Inventors…” Every time the legislature extends IP terms on existing works, they are creating an ex post facto law. All extant IP should be governed by the IP laws that were in place at the time of its creation/submission.

Putting aside the nature of the BBC, if a person makes a film and owns the copyright, and copyright is of the nature of other property rights, let us say a Mr George Lucas decide that whatever film of Star Wars he owns (if any) is not to be shown, and withdraws it from public showing etc. and Mr X decides to show his copy from a DVD that he owns (but not the copyright), then the question arises of our Mr Lucas “What is your loss? and is damages an adequate remedy, should Mr X show his version of Star Wars. Since Mr Lucas has foregone any claim to royalties from showing his film, he has no claim to loss in royalties, and why should he get an injunction* (an equitable remedy) to stop someone doing something that does no harm to Mr Lucas other than a trifling annoyance? It is not uncommon in English law for an injunction to be refused where damages (an accounting for profits) is an adequate remedy.

*There is an arcane, perhaps obsolete, Common Law remedy of the Writ of Prohibition but that is something I have only heard of like reports from a mediaeval bestiary.

Yes, Simon – although I’d put it differently: all property is intellectual.

And I agree with Mid: in order for courts to enforce property rights, the owner must be able to show damage. That, however, only addresses the practical manifestation of the matter – as I may have been damaged, but am unable to prove it. The world is never going to be perfect for everyone, all of the time.

Mr. Ed, the answer to that is to read the fine print. While recalling DVD’s would be logistically problematic, if that is what the original exchange of IP stipulated, then the contract must hold much as you must vacate a house under the terms of the rental contract (unless you live in socialized cities like rent controlled New York and San Francisco). If the landlord must expend resources to evict you, you are liable for damages. Similarly, the cost of enforcing an IP contract is a damage to be recovered. In both cases, damages incurred by the owner’s loss of control could also incur. What if Mr. Lucas had as part of his marketing plan all along the intent to terminate license to a previous release when a new “Director’s Cut” was ready for market? That is a legitimate (if annoying) business plan. If one doesn’t like that prospect, then don’t buy the product in the first place.

ISTR that there was a very similar case involving iPads or Kindles or some such where content was accidentally released in violation of the originators terms and the media company went out and kinda-sorta surreptitiously removed and refunded.

I’m a little leery of allowing courts to estimate “damage” but if a clear breach of contract is first established, then estimation of damages is long established in Anglo-Saxon law, predating even the creation of “criminal” law AKA crimes against the people/crown/state/etc.

Midwesterner,

In my hypothetical scenario, the DVD recall is impossible, sale of DVD and licence for private use is irrevocable, but Mr X is filling the ‘void’ left by the copyright owner’s decision.

In the erasing situation, I would call the accidental release unilateral mistake and tough on the copyright owner. The recipient ought to be allowed to affirm or reject the deal.

In which case it is seller, not buyer, beware. But I can’t tell from your comments if you are asserting a statutory authority to set the terms of contracts between willing participants, the seller and the buyer of the DVD (and optionally, third party distributors). If you are claiming a statutory authority to interfere in private contracts based on some ‘there out to be a law’ sort of reasoning ‘because this is how I think it ought to be’ hopefully needless to say, we differ.

In the erasing situation, there were three parties, not two. There was the creator of the IP, the media distribution provider, and the buyer/end user of the IP. Again, apparently in disagreement with you, I think that what I think does not matter and that contract terms should be enforced. I presume that at least in the future, iPads, Kindles, etc will have in their end user contracts (EULAs) a clause to deal with accidental releases of IP. With platforms as big as Amazon, it is inevitable that it will occasionally happen and it would be foolish of the distributor to not CYA in the contract.

MidW,

I fear we are at cross-purposes.

I make no reference or claim to statute, I am hypothesizing about copyright being treated like other property rights.

As for erasers, if you entrust your wares to an agent who sells it on to a 3rd party who is without notice of your limit to the agent’s authority, you might find in English law that you have no claim against the buyer, only your agent. Caveat vendor. Similarly where the concept of ‘Equity’s Darling‘.

I can’t see why dicks in these sitiations should be shielded from mistakes, fine if terms allow, but let the negligent suffer.

Possibly. There is always a lot of detail that gets swept under the “metacontext” carpet. We are probably in approximate agreement.

If I were a broker of others’ IP like Amazon or Apple Store or similar, I would put in the EULA that users must comply with efforts to repair mistakes or be considered in possession of stolen property. I would also (as they all do) make completely clear that end users are not allowed to redistribute the IP in any way whatsoever. Something to that effect. If I were an IP creator utilizing a broker I would insist on terms that would facilitate this (and even then, choose a broker very carefully).

Open and flowing IP requires that it be treated as property, visible but protected, not as secrets held closely to prevent undesired use. The benefits of treating IP as property over treating it as secrets are immeasurable. A strong case can be made that the industrial revolution owes its spectacular rate of advance to IP protection and the openness that it not only allowed, but mandated as a condition of protection.

Absolutely. Including the negligent guy who bought a copy of a theater release cut and neglected to read that time limit clause.

With respect to:

I don’t think it should be for the courts or any other function of government to effectively void clauses of contracts because the courts or the legislature decides the clause is without merit. I know it is common, but if I enter a contract with you and you promise to destroy the IP a week from Tuesday, it is not for the courts to decide “no harm, no foul, ignore the contract.” If you aren’t going to destroy it a week from Tuesday, don’t promise me you will in a contract and then say “Just kidding. I’m keepin’ it.“

Mid, in the remark you addressed to me, I quite agree. In fact the root difficulty there exists for any taxpayer-funded (or even partly-taxpayer-funded, as in PBS) project. That is why, for instance, there can never be a resolution of problems of “racial discrimination/affirmative action” in government-provided schools: Some of the people who are forced to pay the piper do not get to call the tune.

It is different in private schools, where at least the parents get to weigh the pros and cons of sending their children to School X or Y or not “sending them to school” at all, and then act on their decision without government’s permission.

With government restricted to its proper sphere of trying to protect persons and their property, a great many of these unsolvable political problems would vanish, POOF!, what problem! (That doesn’t mean there wouldn’t be other problems, but those are properly attacked by individual members of their society, in their own thinking and in their various actions, whether they are writing books or acting as restaurateurs or as customers of same, or providing such charity or generosity or helpfulness as they believe appropriate, or providing medical care, or ….)

The fact that the Constitution grants the government the power to do X in the name of Y does not mean that it does so properly. Perhaps government shouldn’t have the power to do X at all; perhaps it should have that power, or some subset of it, but not on grounds Y as stated.

We can discuss what the (statute) law actually IS, or we can discuss what it ought to be. I’m addressing the latter. Furthermore, I agree with Alisa completely in her observation to staghound: Copyright has beneficial side-effects, but the moral-ethical reason that prompts it is the only reason that puts it within the purview of government and statue law at all, and that is that it protects property rights (insofar as it is humanly possible to do so).

I also agree with Alisa’s follow-up at 4:58 today, as long as “damage” refers to damage to the property right itself (analogous to the medical usage of “insult,” as in “bruising shows the insult to the body”) and not merely financial damage to the copyright holder(s), or physical damage to the property.

Of course, in this Vale of Tears very little is 100% perfect. That’s why we have “fair use doctrine,” and why specific cases of copyright infringement might be hard to decide even under statutes as good as can be devised.

“Natural Law” as applied to humans has nothing to do with the Lion and the Zebra, nor with “Nature, red in tooth and claw.”

Natural Laws are observable principles of the sort “If X is the case then Y will occur, or will not occur, or — as far as we know so far — is likely, or unlikely, to occur.” It is a Natural Law that electrical currents generate heat. It is a Law of Nature that cranial amputations cause death.

It is in fact Natural Law that the Lion preys upon the Zebra, if there happen to be zebra available to a hungry lion. But men are neither lions nor zebras, and Natural Law does not require them to prey upon other men, nor to be preyed upon by others. The fact is that most people, to the extent that they are not messed up by a pathological society, are more at peace with themselves (which is a value for most people most of the time) when they are more at peace with their neighbors — and, of course, vice-versa. (Inner peace is in short supply when there is much fear, especially chronic fear, although one may learn to ignore it to some extent.)

Now, Man has the ability to form concepts far more sophisticated than any other animal’s, if they can conceptualize at all (I gather that some and perhaps many can form at least some sort of mental construct that might be a proto-concept). And Man can reason in the human sense, although some other animals do seem to capable of at least short-term planning, and certainly of learning. Many animals also appear to have a sense of “alikeness” in others of their species and even of other species.

So, men can observe the circumstances of their existence, and can conceptualize about these, and reason about them, in a way that the other animals simply cannot. I do not think that the smartest monkey alive will be inventing the calculus, nor even imaginary numbers. Nor putting a monkey on the Moon.

Since men do possess these capacities, they can notice what furthers their lives, and in what senses, and what are the implications of X for themselves and those they care about — even where X isn’t even a physical existent but rather a highly abstract theory, an understanding (right or wrong or partly either) of the way the world works.

It is Natural Law the men use these capacities to form theories about what they should or should not do with regard to other men, and other animals, and even themselves. We do this because it is our Nature.

Innate urging causes us to try to increase our satisfactions and decrease our dissatisfactions. This, too, is a result of Natural Law.

And as a result, one component of Natural Law concerns what we call morality; one subset of that is ethics, and another is individual health, both the clearly-physical and psychological or mental-emotional aspects of it. A healthy ethics promotes a psychologically healthy individual; and vice-versa.

Because it is our nature to Reason (as best we can), we aim to conceptualize the way we ought to treat ourselves and each other in a way that increases our satisfactions and decreases our dissatisfactions, and the relations among these conceptualizations. The result is a theory of morality, upon which we proceed to base our moral codes (plural because each individual has his own code; although there seems to be a strong drive for most of us to bring our codes into some sort of concord with the codes and the expectations and the shown approval and disapproval of other people).

In this sense, a proper theory of morality or of moral behavior is based upon Natural Law, which is nothing but the principles (insofar as we can discern them) of the operations of the Universe.

Not everyone has this concept of Natural Law; but I am not Everyone.

Mid,

‘…[I]f I enter a contract with you and you promise to destroy the IP a week from Tuesday, it is not for the courts to decide “no harm, no foul, ignore the contract.” If you aren’t going to destroy it a week from Tuesday, don’t promise me you will in a contract and then say “Just kidding. I’m keepin’ it.“’

Yes, that’s an excellent point. In light of my own comment above about “damage,” defaulting on a contract does constitute damage to the principle of property rights. From the POV of legal philosophy, that’s why we have contract law in the first place.

On the other hand, haven’t you heard of (what I understand is mistakenly called) the Coase Theorem? */sarc*

Somebody has said that what it actually does is create a legal order in which the judge decides a case not on the basis not of whether X’s property was damaged, but by the relative degrees of suffering between the two opponents if he decides for one instead of the other.

First, a disclosure. I started from, and held for very many years, a “Natural Law” view of the origin of moral code. As I hung around this legendary philosophers’ dive blog, I began thinking on a much more encompassing scale. The phrase that originally I loved for its lyrical cadence and beauty, “We hold these truths to be self evident” turned out to be the key to the problem. What is self evident to one is not necessarily self evident to another.

Either coexistence must be achieved by the strongest debater’s threat or use of force to ensconce his “self evident” reality on the both of them or the two parties must reach terms by negotiation. Reach terms that do not require faith or belief in the “why” of the terms (that is rare and unnecessary), but only a willingness to reciprocally adhere to them.

The way it works whenever a higher truth is cited as foundational is –

You perceive your perception and apply your logifications and arrive at “Natural Law”. It’s obvious to you.

I perceive my perceptions and apply my logifications and arrive at “Natural Law”. It’s obvious to me.

If we identify different and perhaps contradictory “Natural Laws” then you are right. Or is it I am right? I has a confused. Maybe we need to have a third party decide which is right. I’ll pick the arbiter. Or do you get to? Let’s vote on it majoritarian stye.

And from this is collectivism wrought.

Where I’ve arrived at now? I reject any foundation for a moral code that relies on the perceptivity and intelligence of humans. In short, I yield to nobody the right to claim “I have the truth!” Importantly, even if I agree with them and the narrative they spin, I can never declare truth as a basis for interactions with others and still claim individuality. “Truth” must be held in common. Human interaction can only be based on consent or violence. If it is based on consent to rules of interaction, then justifications for them are unnecessary. If it is based on violent imposition of the rules (or lack of rules) of interaction, justifications are useless.

Since I will not yield to anybody elses’ claims to “truth”, I can hardly claim my own observations and extrapolations as “truth”. Seriously, if you want to learn a lot of new “natural laws”, have lunch with an enthusiastic progressive.

I agree with that, Julie – very well put indeed.

Mid, as I see it, Julie’s point is not an epistemological one, as not even a practical one. It is simply an observation of how things work. We can argue until the cows come home home about the epistemological soundness of gravity (and don’t even start us on the scientific definitions thereof), but the simple truth is that gravity is part of Natural Law for all our mortal intents and purposes. Epistemology is important, and yet we don’t jump from highrises without a parachute. IOW, both you and Julie are correct, there is no contradiction. Sorry for budging in in any case.

Alisa, feel free to FAIL to budge any time you like, since you tend to be interesting, thought-provoking, and generally sound. In the unlikely event that you meant “barging” (LOLOL), no apology necessary.

Also, thanks for understanding my point and rephrasing it in under 2000 words. 😉

It’s more just an example of universal short-sightedness; Japanese games companies, especially notoriously incompetent ones like Sega are known to carelessly throw away source code like sweet wrappers. In the case of Propeller Arena, which was never released (the lame excuse apparently being 9/11), “piracy” has enabled people to actually play the game whereas had the magnificently stupid Sega of Japan had their way, no one would be able to play it. Of course, in the case of Panzer Dragoon Saga, the source code has been lost forever, allegedly due to petty politics.

And let’s not forget the Magnificent Ambersons, butchered by RKO and its original cut destroyed.

Welles lost control of the editing of The Magnificent Ambersons to RKO, and the final version released to audiences differed significantly from his rough cut of the film. More than an hour of footage was cut by the studio, which also shot and substituted a happier ending. Although Welles’ extensive notes for how he wished the film to be cut have survived, the excised footage was destroyed. Composer Bernard Herrmann insisted his credit be removed when, like the film itself, his score was heavily edited by the studio.

Even without being “lost” there are still many productions that are extremely difficult to get hold of. The ABC production of “Brave New World”, Disney’s “Song of the South” and the BBCs “The Enchanted Castle” of which Wikipedia shamefully says “The Enchanted Castle was adapted into a TV-miniseries by the BBC in 1979. It has not been released on DVD or VHS in the UK, however, a DVD was released in Australia on 03/07/2013” for examples (there are many more but these are three I have wanted to view in particular).

At least it *is* possible, in the modern world, if one is a flexible with legalities to track down copies but the quality is… less than desirable, typically being taken from very old and well worn VHS tapes (so I hear). Copyrights are supposed to be bargains with the content producer to provide them limited monopoly in exchange for the benefits it provides “society”. We have allowed people to become curators of our culture and they have dropped the ball, quite badly. It is way past time that a redress of the balance was made.

Though it has to be said that at least this has only been a brief period in our history. Near perfect copies of virtually everything will be available, one way or another, going forward. It is up to those producing the content to make an offer that people find acceptable or face being left out of the equation (whatever the legalities or rights and wrongs).

I was reading that only a very small fraction of the earliest movies actually survive, many of them in perilous condition (or was I being told by Clint Eastwood?) and some key figures in the early movie industry have no surviving works. It seems incredible (well, it *is* incredible) how much has changed in such a short time.

Last go. I see “Not only but also” mentioned above. That is one that should really boil the blood.

I havent noticed (or have missed) the biggest bugbear about copyright material. The absurdly long ownership times. There is no reason a movie should have longer protection than an industrial or medical patent (to pick 2).

Also the music and film industry have had the ability to see who has brought their music for a couple of decades, but invests almost nothing in “portable copyright” (I buy an album, then lose my password and computer/record) meaning i may pay for the same right to use that material multiple times over my lifetime. The creative industries appear to be trying to have their cake and eat it as well, they want unlimited powers to own the copyright, but extraordinary power to limit your “ownership” for personal use.

6-10 years is plenty of time for copyright over “creative” material, anyone think of a reason why not?

Richard Thomas

I wonder if the dastardly “political incorrectness” of not only, but also saw it put down the memory hole?

That is deliberate vandalism, but let me guess no-one was ever sacked for it?

MidW

But it is for the courts to decide, lest justice be s rubber stamp. Nemo judex in causa sua is the principle you reject. Were it otherwise, there would be no end to spiteful and vexatious litigation.

And even if not, the courts would not ignore the contract in your scenario, the court would assess remedy for breach.

Richard Thomas: Yes things have changed in such a short time. For instance, when Verdi was preparing his opera Rigoletto for its premiere at La Fenice :-

Of course we will never see that original production of Verdi’s masterpiece but the Royal Opera House’s DVD of McVicar’s production of Rigoletto will be available, (heavily copyrighted), for a while yet.

It’s probably a bit of a shame that some episodes of “Not only but also…” and Dr Who are lost, but so are the original performances of the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides amongst many others. Fortunately in some cases the scripts remain and anyone who feels the need can, after resolving any necessary copyright issues, recreate at least some semblance of the originals.

…yes, ‘barge’. Barge, that’s it. Barge. Thanks Julie – I only now see how tired I was last night :-O

Mr. Ed, you are rather selectively editing the argument. In full it is:

I reiterate, it is not for courts to void contracts because they think the terms are a waste of resources, “just plain stupid” or any other reason. If the contract was freely and knowingly entered into by both parties, if they each gave their informed consent, then it is the courts job to understand and apply the contract, not replace it with a new and different contract that the court finds more appealing. That you argue otherwise is out of character with the general tenor of views you usually express here.

If you are conflating my separate discussion with Julie regarding the foundations of personal moral codes and citing “Nemo judex in causa sua” as grounds for collectively divinating “Truth”, that is disingenuous. Either that or you are advocating for the creation of thought crime. My point with Julie is that I give my consent to terms of societal association for my own reasons. I neither concede nor demand agreement on the moral foundations for the terms, only on the ‘executable code’ they contain.

I like it when you budge in, Alisa. You should make a habit of it. 🙂

MidW

I am not selectively editing your argument, I am simply pointing out how the legal syste works, here in England anyway. Nemo judex flows naturally from a failure to permit the law to distinguish liability and remedy. Specific performance of a contract in English law is always in the discretion of the court, as it is an equitable remedy.

On “Natural Law”:

In 2009, a panel including classic liberal or libertarin-ish Prof. Richard Epstein of the NYU and U. of Chicago law schools and Prof. Jed Rubenfeld of Yale L.S. discussed “Redistribution of Wealth” at the National Lawyers’ Convention.

Here, if the html works right, is the final 5:48 portion of the Q&A of the 11-part video series of the confab. Former law prof and co-founder of the Federalist Society Lee Liberman asks how you answer when someone proposes that Shari’ah is derived from Natural Law, since Shari’ah is a matter of decree whereas presumably N.L. is based upon human nature.

The odious J. Rubenfeld (who, as we already know from his presentation, is Demon Spawn) relieves himself of his opinion in a childishly nasty manner (faces, rolled eyes, etc.), whereupon Prof. Epstein for once becomes really angry and explains the origins and meaning of “Natural Law” as he has come to view it. This is well worth seeing for the entertainment value alone, even if one has no interest in the issue. Enjoy! (If the embedment doesn’t work, the URL is

http://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=k7rYKJYj308“>

The whole thing (11 short parts) is well worth watching. Steve Forbes and Andy Stern are also on the panel. Judge Harvie Wilkinson, of the Fourth Circuit (Maryland, the Virginias, the Carolinas), presides.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7rYKJYj308?rel=0&w=420&h=315%5D

Dear Mods, the Spam-bot suspects my UT links of subversion. Could you please soothe it? Thanks, :>))

–J.

Self-described “radical libertarian” (no, thank goodness, not of the Rockwellian/LvMI type) and classical liberal Prof. Randy Barnett of Georgetown has done a great deal of work on Natural Law and “Natural Rights” and the relation between them.

Last spring Cato presented a “Free Thoughts” 54-minute podcast

http://cdn.cato.org/libertarianismdotorg/freethoughts/FreeThoughts_034.mp3

in which Prof. Barnett discussed the new, second edition of his book The Structure of Liberty with Aaron Powell and Trevor Burrus of Cato. He began by describing these theories, and the basis of the term “Natural Rights.” He explained that Natural Rights theory aims to define a space within each individual can exercise his natural autonomy, or self-determination, without interference–usual caveats–from others, who of course enjoy like “spaces” for themselves. The nature and extent of this space are derived by reason from Natural Law and its implications.

His relatively short paper “A Law Professor’s Guide to Natural Law and Natural Rights,” from 1997, also outlines his thinking, stressing various points. In my opinion, it is Not to Be Missed:

http://www.bu.edu/rbarnett/Guide.htm